A Biologist Looks at Cities

Coro, the Birthplace of Venezuela

When architects look at cities, they see buildings; when urban planners examine cities, they envision infrastructure. As a biologist, when I look at cities, I see plants.

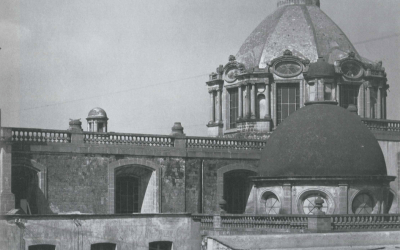

Coro, a Caribbean enclave in northwestern Venezuela, is surrounded by xerophytic vegetation—cacti, aloe vera and agave cocui—plants that can live in a desert environment. Coro now earns its living from tourism; many tourists enjoy the colonial architecture of this UNESCO World Heritage Site. Founded in 1527, Coro competes with Cumaná as the oldest Spanish city in the Americas. But behind the well-preserved colonial houses with thick walls of adobe and red tile roofs, there is a biologist’s tale.

Indeed, the history of Coro, the colonial city where I work, is intricately tied to its vegetation. Residents of surrounding towns still earn their living from the products of agave cocui, a cactus-like plant known locally as cocuy and dubbed the “marvel plant” in 1567 because of its versatility.

Since pre-Columbian times, Coro’s architecture and physical setting has been linked to the intensive use of its native vegetation. Houses in Coro were constructed on top of a frame made from cactus wood and magueys. When tourists peek at the houses’ colorful contrasts, from deep indigos to intense burgundies and ochre yellows, and snap pictures of the central patios and colorful gardens, they are not aware (unless they happen to be biologists) that this unique picturesque tropical gallery is rooted in plant life.

In most old houses, backyard orchards called huertas include coconut palms, mango, guava and lemon trees. The combination of native trees and trade winds create a microclimate much cooler than outside in the street. It appears that early settlers in Coro understood the intimate relationship of humans and plants. They realized both the utilitarian purpose of fruits and landscaping as well as the shade trees’ function as moderators of temperature and alleviators of humidity.

The Caquetios and Jiraharas, the original inhabitants of Todariquiva (now Coro), treasured native plants. Their buildings, religious rituals, and food were derived from agaves, cacti and cuji and dividive, native relatives to mesquite. They used these plants, called cocuy de penca, to make their bedding and hammocks, as well as an alcoholic drink used in their rituals. Illustrating that biology cannot be divorced from history, this ritual drink played an important role in a peace treaty between native Indians and the Spanish.

It is said that agave cocui dominated the landscape of the Province of Coro, which was a large area of land that occupied almost a quarter of Venezuela’s present territory. The agave cocui gave rise to a Venezuelan drink, cocuy pecayero, trademarked in 2001. As an export product, like Mexican tequila or French champagne, this plant-based product became an alternative source of sustainable development for a very poor community located in a tropical semi-desert, where most plant cultivation is impossible.

The beautiful sand dunes around Coro are home to cacti and local mesquites called cujies, which resemble umbrellas. From the cacti, inhabitants of Coro harvested fruits and built basic furniture, a common custom until the last century and still promoted to this day. Cacti were also used for clearing water sediments; local residents say that a piece of cacti was put inside the water reservoirs to agglomerate the suspended particles cause the colloids to sink, cleansing the water.

Multiple uses of the mesquite are also documented—from protein-rich “lollipops” to building and fence construction. The dense mesquite wood is so strongly protected by natural gums or resins that it can last at least 500 years. In fact, the first cross ever built in Venezuela and perhaps in all of South America was constructed with mesquite wood and is still standing in the Plaza de San Clemente, next to the chapel with the same name in Coro. It is speculated that it was built in approximately 1527 for the celebration of Coro’s first Catholic mass by order of Don Rodrigo de Bastidas, the first Bishop of Coro and Venezuela.

Appropriately, Coro will always be linked to the often neglected but exuberant xerophytic vegetation that seems to have survived significant climatic changes. Even though residents of Coro may now cut down trees in a misguided attempt at cleanliness or in order to vacate space for power lines, Coro’s vegetation-based history is successfully resisting multiple pressures from development and construction.

Indeed, research into the uses of agave cocui has transformed it from an extractive pastime to a cultivated product, with many possibilities for commercial utilization. One wonders if the successful use of these plant products may soon return Coro to its historical biological roots.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

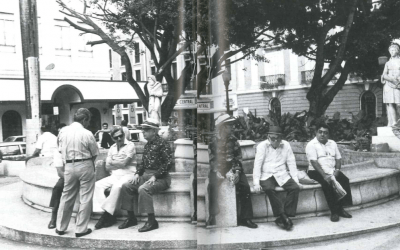

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….