A Crooked Gauntlet

The Plight of Migrants in Mexico

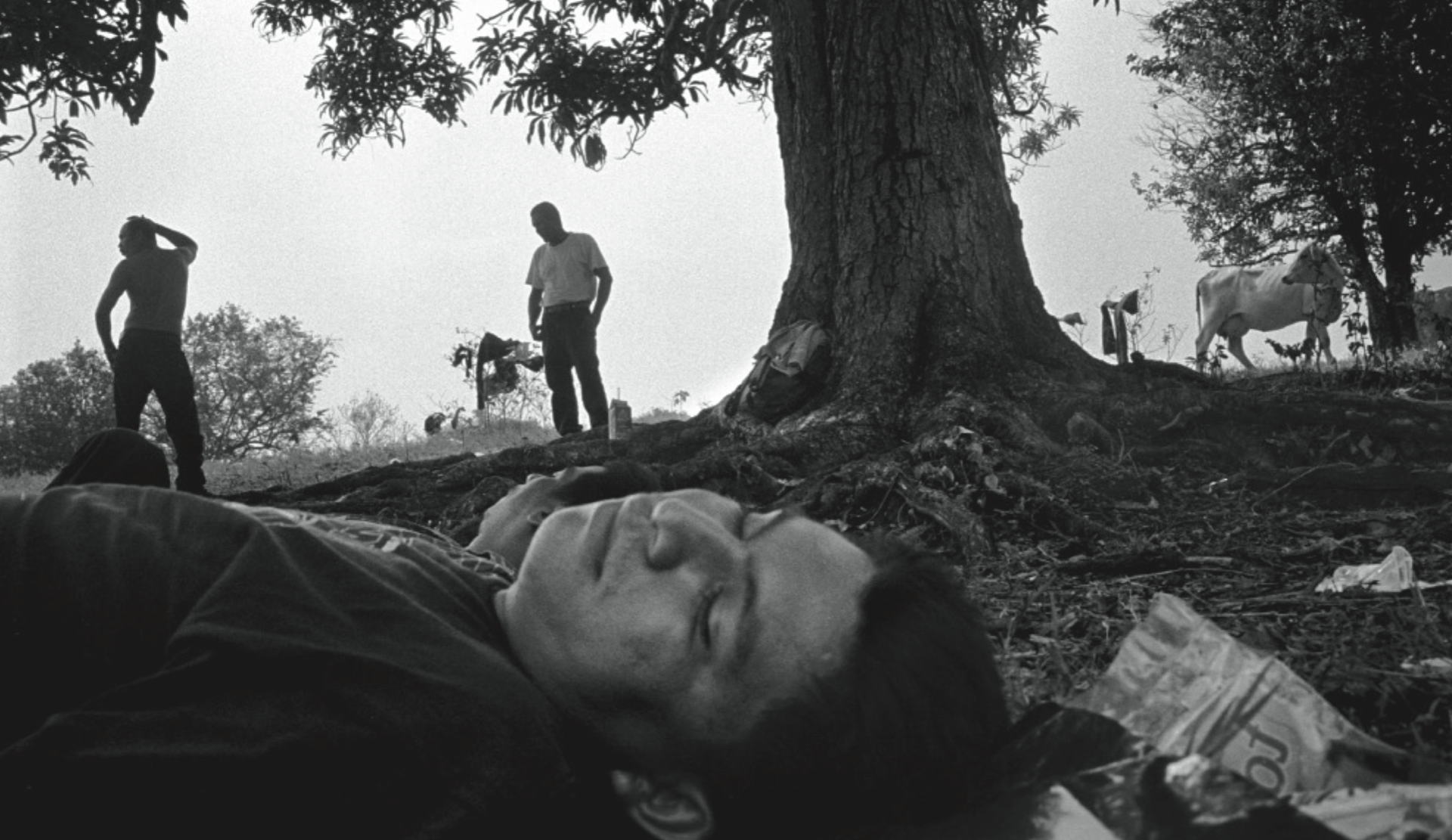

Guatemalan migrants nap in Tenosique, Mexico, before boarding freight trains. Photo by Jon Lowenstein/Noor.

More than a hundred Central Americans —including 21 minors and three infants—had been trapped in a forced labor camp in the city of Tuxtla Gutiérrez until discovered by Mexican authorities in November 2010. Seven months later, three truckloads of gunmen stopped a train traveling north from Oaxaca and reportedly forced sixty Central American migrants into their vehicles. Mexican federal police rescued 12 migrants (eight Central Americans, three Brazilians, and an Iranian) from their captors in Tamaulipas. All told, in the last half decade, the Mexican Human Rights Commission estimates that at least 20,000 Central and South American migrants were kidnapped each year, or more than 50 a day. Many did not survive: at least 150 clandestine grave sites have been identified in over 22 Mexican states, many of them containing the remains of migrants and other victims of the country’s ruthless organized crime groups. The best-known incident was the discovery of 72 murdered migrants in mass graves in San Fernando, a number that soared to the hundreds after further investigation.

At first, San Fernando, a small farming community of about 60,000 people, located about 100 miles south of Brownsville, Texas, may have seemed exceptional. However, over time, greater scrutiny revealed a broader pattern of violent organized crime groups targeting migrants.

The proliferation of violence in Mexico adds a new and unwelcome peril for the migrants who have traversed Mexico over the last three decades in search of a better life in “El Norte.” During that period, the volume and pace of migration from Mexico and Central America had grown to unprecedented levels, due to economic instability, internal displacement, and various forms of violence in their home communities. The wave began during the so-called Lost Decade of the 1980s, when Mexico and its neighbors were bedeviled by crushing debt, hyper-inflation, unemployment, and various degrees of internal strife. The wave continued during a new era of economic reform, globalized trade, and newfound prosperity in the 1990s. Even as the wave began to wane over the last decade, due largely to a sputtering U.S. economy and changing demographics in migrant-sending countries, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Central Americans continue to flee from misery each year.

Migrants fleeing violence add another layer to an already existing situation. According to figures tracked by the Trans-Border Institute’s Justice in Mexico Project (www.justiceinmexico.org), by year’s end the number of drug-related killings in Mexico since 2006 will reach nearly 50,000 dead: more than one every hour. Violence has grown so pervasive that tens of thousands of people within Mexico have been uprooted from their communities, seeking refuge in other parts of Mexico or abroad. In March 2011, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre issued a report stating that there are an estimated 230,000 people displaced within Mexico. While a range of factors contributes to displacement, including political violence in southern states like Chiapas, most of these internally displaced people have been driven from locations severely affected by violence among drug trafficking organizations. These violent spaces include key corridors for domestic and transnational migration in the transit states of Coahuila, Chihuahua, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Tamaulipas, Tabasco, Veracruz, Oaxaca, and Chiapas.

In response to the waves of migrants, U.S. authorities started introducing tougher border security measures in response to demands from citizens disturbed by the latest tide of “new Americans”—even before the added pressure came from those fleeing escalating violence. The number of Border Patrol agents grew from 2,900 in 1980 to around 4,000 at the start of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994. Fears that NAFTA would facilitate more immigration and drug trafficking brought new concentrated border enforcement measures, such as Operation Hold-the-Line and Operation Gatekeeper, which poured millions of dollars into new fencing and high-tech surveillance systems intended to gain operational control of strategic corridors along the border. By 2000, the size of the Border Patrol more than doubled to more than 9,000 agents. In the new millennium, the 9/11 attacks placed new urgency on homeland security and led the Bush administration to continue efforts to beef up southwest border enforcement. Additionally, southwest governors sent hundreds of National Guard troops to the border for extended deployments throughout the 2000s to shore up federal immigration controls and counter-drug efforts. Under the Obama administration, the Border Patrol grew to more than 20,000 agents, and more than 3,000 Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents were sent to the border to bolster efforts to combat arms and cash smuggling by drug traffickers.

Ironically, tougher border enforcement unwittingly encouraged the development of more sophisticated organized crime networks, including both powerful drug-trafficking organizations and a new generation of professional smugglers or coyotes, who promised safe passage for higher fees. In fact, there is increasingly little distinction between the two modes of smuggling, since the organized crime groups have conglomerated and diversified significantly in recent years. The implication for migrants is that their coyotes are no longer part of “mom and pop” smuggling operations, but increasingly involved with more extensive and ruthless illicit business operations.

People who are poor and dislocated are easily exploitable. Criminal groups take whatever money migrants and their families can muster, or demand future payment in the form of indentured servitude. Moreover, as border security measures have disrupted once circular patterns of patriarchal migration, women and children have become ready and vulnerable targets of predation. While it is true that migrants have long been the targets of bandits, corrupt authorities, rapists and other criminals, the gauntlet of predation that migrants navigate from Tapachula to Tijuana has become even more terrifying in recent years. One major source of danger is the Mara Salvatrucha, a transnational Central American gang that has gradually expanded into several states throughout Mexico, including the Federal District, Baja California, Tamaulipas, and Nuevo León.

In addition, migrants now face well-armed and highly trained organized crime groups like the Zetas, founded by elite Mexican military operatives. The Zetas broke with their former employers in the Gulf Cartel in 2010 and began to work with former Kaibiles—Guatemalan special forces—to support their operations in both Guatemala and Mexico. They have earned a reputation as one of Mexico’s most dangerous organized crime groups, in part because of their calculated exploitation and killing of migrants. In April 2010, in the northeastern border state of Tamaulipas, a young man from Ecuador escaped from captivity on a Zeta-operated ranch in the town of San Fernando, leading authorities to a mass gravesite, or narcofosa, where they identified the remains of 72 people, mostly migrants. In April 2011, authorities found 193 more bodies at over 40 different locations in San Fernando. In both cases, many of the victims originated from Ecuador, Honduras, Brazil and El Salvador, and were reportedly killed for refusing to work for the Zetas.

If drug trafficking is so lucrative, then why have poor, desperate migrants become a key source of revenue for organized crime groups? Part of the explanation is that, as these groups have begun to splinter and fight among themselves, they have had to supplement drug-trafficking revenues by diversifying into other forms of illicit activity. Migrants are a multi-purpose and often reusable commodity. When treated as paying customers by smuggling organizations, they can be charged for passage to the United States. Even after paying between $3,000 and $7,000 for “safe” passage, migrants are forced to call their families to beg for additional money to pay their captors. Based on its interviews, Mexican human rights authorities found that ransoms demanded by kidnappers ranged from $1,500-$5,000 (USD), with an average of $2,500 (USD). When kidnapped, the victims can be used for forced labor or sexual exploitation, even as their families at home or in the United States are paying ransom. According to a United Nations estimate, aggregate revenues from the smuggling and kidnapping of migrants traveling through Mexico probably amount to as much as one billion dollars, not counting the more than six billion in revenues for smuggling migrants across the U.S.-Mexico border.

Would that these vulnerable migrants could turn to authorities for help. Groups like Brothers Along the Road (Hermanos en el Camino) and Step by Step Towards Peace (Paso a Paso Hacia la Paz) have urged authorities to devote greater attention and protection to address the plight of these and other migrants travelling through Mexico. Unfortunately, many authorities are actually in league with organized crime groups or directly involved in exploiting migrants themselves. In March 2008, a group of Central American migrants was attacked by officials of the Instituto Nacional de Migración (INM) and naval officers in the community of Las Palmas, Oaxaca. In July 2010, Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission found that federal agents of the national Public Security Secretariat stopped a train traveling from Chiapas to Oaxaca, forced 50 migrants to descend, and robbed them.

Recent developments suggest that there has been some progress on the part of the Mexican government. In April 2011, soon after the discovery of new mass graves in San Fernando, the Mexican army captured Martín Estrada Luna, “El Kilo,” the alleged Zeta cell leader believed to have carried out the mass killing of migrants in Tamaulipas. Authorities also made dozens of other arrests, including 16 San Fernando municipal police officers that allegedly offered protection to the Zetas and assisted in hiding the mass homicide. The following month, President Felipe Calderón signed legislation to effectively “decriminalize” migration, eliminating criminal penalties for unauthorized immigrants to make it more difficult for corrupt authorities to exploit them. In October 2011, the Mexican government fired over 120 corrupt agents of its National Immigration Institute after revelations of their involvement in the abduction, rape, prostitution, and murder of migrants in the states of Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Sonora, Tabasco, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz, and the Federal District.

Efforts to reduce the threat posed by corrupt officials are a good first step, but additional measures could be taken. Mexico should consider bilateral agreements with Guatemala and its other Central American neighbors to develop shared approaches to managing immigration flows, more effective management of border entry points, and protections for the basic safety and human rights of migrants, regardless of their immigration status. Doing so would provide a precedent and a model for the United States to do the same, perhaps as part of a grand bargain to increase visa quotas for Mexican citizens, who represent the vast majority of undocumented immigrants in the United States. More realistically, the United States would also do well to ensure that the deportation of undocumented immigrants back to Mexican border cities does not put them at risk to victimization or recruitment by organized crime. The development of bilateral agreements with local Mexican authorities to reduce the risks factors for returning migrants (e.g., alerting Mexican authorities, returning deportees at safe times of day, interviewing migrants regarding victimization in Mexico, etc.) would be a step in the right direction.

Spring 2012, Volume XI, Number 3

David A. Shirk is assistant professor of Political Science and director of the Trans-Border Institute at the University of San Diego.

Related Articles

Haiti After The Quake

There is always movement in Haiti. The political, social and ecological terrains are ever-shifting, yet they remain intrinsically connected. Thus the island’s tropical ecology once lured…

Investigating Organized Crime

Medellin, Colombia, February 2009. Two journalists, with more than twenty years of experience between them covering Latin America, were engaging in a familiar lament over a couple of beers. Nobody was paying for serious investigation of organized…

Keys to Reducing Violence in Mexico

Some regions of Mexico now seem like war zones. Nineteen out of the 50 most violent cities in the world are expected to be found in the country by the end of 2011. Yet severe violence is…