A Look at the Galapagos

When my parents learned that San Cristobal, Galapagos was the site placement for my WorldTeach volunteership, they breathed a sigh of relief. Amidst political turmoil on mainland Ecuador, including a coup on the presidential palace just three months prior to my departure, and a severe economic crisis, the Galapagos Islands seemed far away from the violence and political instability of mainland Ecuador. Neither of us knew, however, that the Galapagos, often heralded as a paradigm of the delicate balance between conservation, tourism, and local interests, were also grappling with a different set of social dynamics that threatened the extraordinary ecosystems of these remote isles, and the lives of the people that inhabit them.

In fact, in my one year in the sleepy village of Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, I experienced a potentially devastating oil spill, a hostile takeover of the Galapagos National Park (GNP), the Charles Darwin Research Station (CDRS) offices and my ESL classes by local fishermen, massive depletion of marine resources, particularly sea cucumber and lobster, and the assault of a Park ranger. Shortly after I left, 15 sea lions were mutilated for the sale of their teeth and sexual organs. So dramatic have been the threats to conservation have been so that some scientists have begun to suggest that if the Galapagos—the paradigm of successful ecotourism—can’t be protected, then nowhere in the world can.

In 1934, after centuries of species devastation from buccaneers, whalers, and fur sealers, the government of Ecuador designated some Galapagos Islands as a wildlife sanctuary. In 1959, Ecuador declared 97% of the islands as National Park land, and in 1986 the Galapagos Marine Reserve was officially established, although mostly on paper. Located 1,000 kilometers off the Ecuadorian coast, the Galapagos Islands are often referred to as the birthplace of modern day ecotourism, which, alongside fishing, has for many years been the principle means of income for the few thousand inhabitants of Santa Cruz, San Cristobal, Isabela, Baltra, and Floreana islands, or the “inhabited” islands of the archipelago. First attracting visitors in natural history in 1967, the pioneers of Galapagos ecotourism had well-organized visitation by 1985, using locally owned, low-impact, live-aboard boats that conducted tours ranging from three days to two weeks for small groups. The GNP designated more than 60 visitor sites on the islands, each with clearly marked trails, and certified naturalist guides were required to accompany visitors during site visits at all times, a practice that continues today.

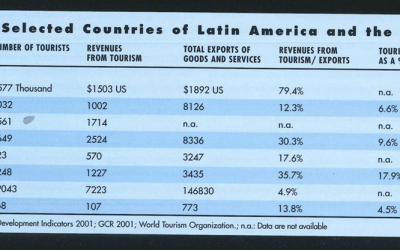

Since the 1980s, however, immigration of mainlanders seeking economic opportunities in ecotourism and fishing, and in some cases both, has averaged 5% per year, boosting total population from roughly 4,000 in 1980 to over 15,000 today. Tourism has also boomed as the number of visitors to the Galapagos National Parks has increased from roughly 10,000 in 1979 to more than 60,000 today amounting to $60 million annually. The impacts of these resident and visitor explosions are numerous. Increases in the incidence and numbers of introduced species, dramatic increases in the extraction of marine resources, legally and otherwise, a housing and construction boom, increased marine pollution, and overcrowded schools just to name a few. Further, as revenues from fishing and tourism soared, so too have the conflicts between the fishing sector and the conservation sector, made up of tour operators, international conservation organizations, primarily the CDRS and the GNP.

For many San Cristobal residents, conservation is in some ways a dirty word. Some residents see the GNP, with its deep pockets and strict rules, as concerned with the protection of every species except humans, and view their mandate as a threat to the local means of living. But the attitudes of residents, both new and old, stem from policies adopted several decades earlier. Paola Oviedo, a consultant who has studied the conflict resolution process in Galapagos, points out that, “The conflict in the Galapagos is the result of the (traditional) approach to protected areas.” From the beginning, residents felt shut out of the process that had imposed conservation measures. (Reports Magazine, October 6, 2001) The CDRS, too, was highly centralized, focusing its efforts almost exclusively on scientific research, perhaps helping sow the seeds for future conflict.

In 1997, after a hostile takeover of the GNP and CDRS offices by local fishermen, a process of conflict resolution resulted in the 1998 Special Law for Galapagos. The Law officially recognized the 40 nautical miles surrounding the archipelago as a protected area, restricted fisheries in the Reserve to artisan fishing by registered members of the islands—four cooperatives, established a structure and strict rules to control immigration, and other regulations for tourism and other areas. It also created the Participatory Management Board, a mechanism for representatives of fishing, tourism, and conservation to collaborate on planning and managing the activities in the Reserve, as well as the Interinstitutional Management Authority (IMA), headed by the Minister of the Environment, and encompassing both government departments and primary stakeholder groups as the Reserve’s highest decision making body (www.darwinfoundation.org). At the local level, it created an incentive for previously ignored parties to participate in the process, helped build consensus, increased transparency, and reduced conflict, at least temporarily.

Unfortunately, however, conflict returned over lobster fisheries just two years later. In 1999, after 500 local fishermen harvested 54 tons of lobster in four months, the IMA established a quota of 50 tons in a maximum allowable time of four months for the 2000 lobster campaign. Barely two months into the 2000 campaign, however, 54 tons of lobster were captured as the number of fisherman nearly doubled despite a five-year ban on new membership of the fishing cooperatives created by the Special Law. Supported by local politicians, the fishing community again went on strike, destroying the home of the Director of the GNP on Isabela Island, disrupting tourist activity, and preventing employees of the GNP, CDRS, and strangely enough WorldTeach, from working for several days. Armed guards were flown from the mainland to ease the situation. After failed negotiations, including the fishing sector’s rejection of an offer by the CDRS and others to increase the original quota, the lobster season reopened for a short time.

The implications of social upheaval as a successful negotiation tactic are worrisome. More troubling is the impotence of the GNP to enforce the Special Law, partly due to the failure to create follow-on legislation necessary for the Special Law to become effective. Fortunately, so far into the 2001 campaign, the lobster populations seem to be healthy and the numbers of registered fishermen and boats well managed. Conversely, the 2000 sea cucumber harvest, another politically charged fishery, which first started along the coastland of mainland Ecuador in 1988 only to be virtually wiped out three years later, featured schoolteachers, some students, and public officials taking paid vacation in order to get in on the gold rush. The outcome was an oversupply of fishermen and numerous tragic accidental deaths of untrained divers. By the close of the 2001 sea cucumber season, however, the fisherman collected less than three quarters of the four million quota, suggesting that years of overfishing have already begun to take its toll on local supply.

Ecotourism and conservation also face pressures from mainland Ecuador and Central America, mainly from fishermen interested in shark, tuna, and sea lions for export to Asia and other parts of the world. Thanks in part to the donation of a high-speed boat from the Sea Shepherd conservation organization, five boats were captured fishing without authorization within the 40 nautical miles surrounding the islands in July 2001. Upon inspection, GNP authorities discovered thousands of shark fins believed to be part of an export trade to Asia. Though the addition of the modern vessel to the GNP’s fleet has certainly helped monitor the 51,000 square mile Reserve, alleged corruption from Ecuadorian Navy officials, charged with sanctioning perpetrators of the Reserve, has limited its success.

Media attention on the “violent and uncompromising” fishermen, however, has slighted the debate as bad fishermen versus earth loving conservationists. Moreover, it has overlooked the greatest threat to the long-term, ecological health of the Islands, introduced species. With 60,000 tourists visiting the Islands annually, the arrival and dispersion of introduced species are the greatest environmental threat currently facing Galapagos, and are directly related to ecotourism. A quarantine system (SICGAL) set up under the Special Law manually checks all handbags at the airport, and incoming freight from the mainland, but the presence of goats, frogs, rats, blackberries, dogs, feral cats, ants, flies, and pigs continues to threaten the high degree of endemic species exclusive to the Galapagos.

An estimated 75,000-125,000 goats inhabit Isabela, the largest island in the Galapagos. Isabela is also home to the highest concentration of endemic species in the archipelago, including roughly 50% of the giant tortoise population. (www.darwinfoundation.org). Causing land erosion and a tremendous consumption of vegetation that the tortoises and other species depend upon for survival, the GNP has strategically hunted the goats on Isabela and other islands for years. This year, the GNP, in coordination with the United Nations, USAID, and others, has begun a multi-million dollar eradication campaign featuring trained professional hunters, and methods used successfully in eradication projects in New Zealand. While Project Isabela and others like it are essential for the conservation of these unique islands, their goals are extremely difficult to achieve.

Nonetheless, the conservation strategies of the GNP and CDRS, and the activities of the tourist sector have broadened to include the interests of the human species to a greater extent. Operations of the GNP and CDRS are more decentralized, and measures have been put in place to enable a more equitable, balanced, and sustainable future for the islands. Examples include legislation requiring all naturalist guides to hold a permanent resident card, programs offering fishermen alternative income sources that also benefit the environment, tours of the islands available to local teachers in exchange for participation in environmental education workshops, college scholarships for local students, and many others. Unfortunately, years of perceived secondary treatment, mismanagement of immigration controls, and disasters, including the January oil spill caused by the grounding of an oil tanker carrying fuel to tourist vessels, have made the task of local public approval very difficult. In addition, years of negligible social investment in schools, hospitals, and other social resources have ill prepared residents for the challenges of simultaneously providing world class tourism and managing one of the largest and most delicate ecosystems in the world.

Once considered the model for ecotourism and sustainable development of protected areas, the Galapagos are now gaining a reputation for social conflict and narrowly averting natural disasters. A surge in visitor and resident levels has altered the social, political, and economic dynamics of the Islands, subsequently threatening to permanently modify the ecological balance that draws visitors and scientists from around the world. Democratic solutions have so far been hard to come by, but real progress has undoubtedly been achieved. Social development, however, still lags greatly behind mainland Ecuador, and poses a challenge for future generations seeking to balance conservation with social and economic growth. Clearly, though, the example of Galapagos offers important lessons. Coordination between different sectors, locally, nationally, and internationally, often opposing and from private, public, and other spheres, is critical. This is particularly true for Ecuador and other developing countries historically characterized by low levels of political participation, instability, personalismo, and regionalism. Finally, successful conservation is as much, if not more, about working with people than it is about protecting animals.

Winter 2002, Volume I, Number 2

Matt Garlick is a former WorldTeach Ecuador volunteer, a non-profit organization affiliated with Harvard that provides opportunities for college students and graduates to work and teach in Costa Rica, Ecuador, Namibia, and China. While in Ecuador, he co-founded the New Era Galapagos Foundation (www.neweragalapagos.org), a non-profit initiative dedicated to providing educational opportunities and local environmental action on the island of San Cristobal. He currently lives in San Francisco and can be reached at mgarlick76@yahoo.com.

Related Articles

Let’s Go

Acapulco was covered in water. After days of constant downpour, the gushing, bubbling water had overrun the inadequate sewer system. In its merciless drive towards the ocean, the flood …

Brazil

Did you know that Brazil has awe-inspiring sites, such as the Iguazu Falls, the Itaimbezinho, and the Amazon rainforest, as well as 2,000 miles of virtually uninterrupted soft white beaches? …

After September 11

The September 11th terrorist attacks brought a more immediate sense of crisis to an industry already experiencing a need for restructuring. With the sudden stoppage of flights and the ..