A Look at Zamorano

Yankee pragmatism transplanted to the tropics

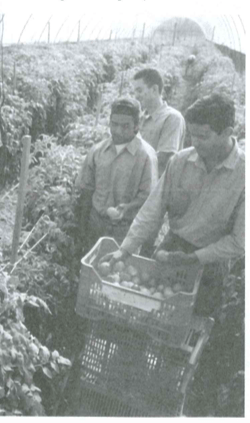

- In the Intensive Crops Enterprise, students learn to produce high- quality vegetables in plastic greenhouses.

Jorge Ivan Restrepo was intrigued. Every morning, he watched his professor leaning on a railing to observe cows as they came in from the pasture to be milked. Finally he got up the courage to ask why. The professor-who was also in charge of the production department- explained he could tell by the way the cows moved if they were sick.

The pastures of Zamorano, a field-based college in Honduras, from which Restrepo graduated as an agronomist in 1982, seem worlds apart from Harvard, where he received his Masters in Public Administration in1998. Yet the two share many links in graduates, exchange programs, and advisory boards.

Restrepo, a 1997-98 Mason Fellow at the John F. Kennedy School of Government who recently directed the Environment Division of FES Foundation, Cali ,Colombia, says that the professor’s answer taught him the value of practical experience.

“From that moment,” he said, “I understood that it wasn’t just important to understand in theory what illnesses attacked cows or the scientific description of those illnesses, but also that one had to look at the way the cows behave and to observe them. At Zamorano, I found the answers to learning in the real world.”

Keith Andrews, Zamorano’s director, agrees.

“All of our students, all of our graduates are proud that they get their hands dirty; that’s very much different from the scholastic tradition that predominates in most other Latin American universities,” he said in an interview on a recent visit to Harvard. “Because we had a strong technical orientation, kind of Yankee pragmatism transplanted to the tropics, it allowed us to attract a strong student body with remarkable faculty to go in a different way from other academic institutions.”

Zamorano, which was Central America’s first private, non-religious college, now has 4000 graduates. Started as an agronomy school with a junior college environment, it has now expanded to a full four-year university curriculum including agricultural science and production, management of agrobusiness, agroindustry (food technology, inducing change in production, both food and lumber); social development and environment. Courses range from animal nutrition and plant physiology to advanced physics and macroeconomics and agricultural policy.

“The first three career areas all focus on making the status quo better and creating wealth,” explains Andrews, who has been at Zamorano 19 years, seven of them as director. “The fourth area is a direct frontal assault on poverty in the forgotten areas of Latin America.” In this part of the program, there is strong focus on converting subsistence farmers into micro entrepreneurs.”

The revised curricula is not the only change at Zamorano. The college, all male students until 1981, is now 23 percent women. Its students and faculty come from way beyond the borders of Central America: last year’s class had 850 students, who came from 23 countries, half from Central American, half from the rest of Latin .America, with a “sprinkling” from Caribbean and Europe, according to Andrews. Diversity has also been encouraged by recruiting among Haitians and indigenous groups, particularly from Ecuador and Bolivia

“We aspire to be the region’s number one undergraduate leadership preparation program,” he added. “Our mandate is to train human resources for Latin America.”

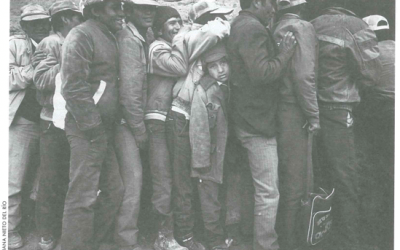

Zamorano uses a two-pronged recruiting program to encourage social diversity in its student body. The first recruits all over the region for students who are self-subsidizing and able to pay tuition that is expensive by Latin American standards. The second recruitment process targets poor, mainly rural high schools and tries to find underprivileged students with academic promise.

“These have shown themselves to be diamonds in the rough, and we grab them up, and we support a lot of them,” explained Andrews. This recruitment effort goes on in 15 countries. Freshman students receive courses to compensate for difference in writing skills and familiarity with the Internet. In many countries, there are pre-Zamorano programs in which students can upgrade their skills in mathematics and chemistry. Zamorano is also working on a distance education program to better prepare future students. Ironically, Andrews observes, the dropout rate for both groups is about the same: poor kids may find the course too academically difficult, while some wealthier students find the program too demanding and don’t like the lack of comfort such as having to take cold showers.

For Zamorano students from wealthier backgrounds, the insitution’s outreach program may be an eye-opener on poverty; for the students from less privileged background, it provides a training ground to take new skills back to their communities. The large outreach program trains about 10,000 people each year, most of them peasants and their families in Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador.

“We are working mainly with hillside farmers on environmental aspects of agricultural production and community development and other environmental issues,” explains Andrews. “And we have done it in a way that has maintained the spirit of the idea that we are here to be supportive of what societies decide they should do rather than us as perceiving ourselves as many academics do as a driving force behind social change. It puts us in a different role in society; we’re here to produce the people that shake up the world, but we don’t shake up the world ourselves.”

In the Dairy and Meat Products Enterprise, students produce yogurt, a dozen kinds of cheeses, ice cream, and milk. These practi- cal activities comple- ment the theoretical instruction offered in Zamorano’s new Food Technology Career.

Students do go on to become leaders, and several graduates-including former Mason Fellow Restrepo-have done postgraduate work at Harvard, with whom institutional links are informal but strong. Francisco de Sola, a member of the Advisory Committee of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, is also on the International Board of Advisors at Zamorano, a group of 25 members from nine countries. Harvard Business School Professor Ray Goldberg sits on the same board. Philip Lehner, another DRCLAS Advisory Committee member, is a trustee, as is DRCLAS donor George Gardner.

Zamorano also has very close links to another Central American institution officially affiliated with Harvard-the Central American Business Institute, INCAE.

“INCAE is different from Zamorano in two ways: they focus on management and business, and they work entirely at the postgraduate level. We work almost entirely on the undergraduate level, so there’s a wonderful complementary there. We probably have 250 of our graduates who have gone on to INCAE,”said Andrews. “As we work more closely with INCAE, we think that will bring us closer to Harvard. Clearly, it is to Central America”s benefit to use any mechanism to bring first-rate human resources anywhere in the developed, wealthy world to bear on the developing problems in Central America, as Zamorano intends to do.”

Zamorano has conducted student and faculty exchanges, sabbaticals, and in-service training with leading institutions of higher education around the world, including Harvard. Other educational partners are Purdue, Florida, Cornell, McGill, and Berlin University, among others. Andrews hopes to strengthen ties with Harvard. One of his dreams is to establish a program with a first rate U.S. college or university that would allow Zamorano students to receive the first two years of a liberal arts education at a U.S. university , completing university on the campus outside of Tegucigalpa “to learn the real issues that confront Latin America and (to) get first-hand experience to complement what they’re studying?wouldn’t it be great if we could do it with Harvard?”

Fall 1999

June Carolyn Erlick is the Publications Director at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. She worked as a foreign correspondent in Central America from 1978-1988.

Related Articles

Poverty or Potential?

Teresa stops me three blocks from Nueva Imperial’s main plaza on a quiet Wednesday morning, eager to chat. She is wearing a light blue sweater and a matching blue headband glowing slightly against her dark black hair.

Infections and Inequalities

I read Paul Farmer’s book while on a short visit to Venezuela, and found that setting, at this historical moment in time, particularly pertinent and highly conducive to the arguments Farmer…

Proclaiming the Jubilee

Carmen Rodríguez heads the Charismatic Movement in a sprawling shantytown parish south of Lima, Peru. She and other lay leaders of the Lurín Diocese have been preparing for the…