A Personal View from the Diaspora

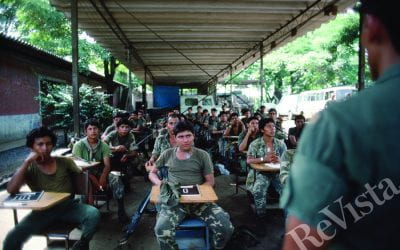

In 1992 the Chapultepec Peace Accords ended El Salvador’s brutal 12-year civil war. The government granted amnesty to all parties, protecting war criminals from even so much as a public confession of their crimes. There was no truth, there was no reconciliation. Attempts at peace and healing manifested as institutionalized amnesia.

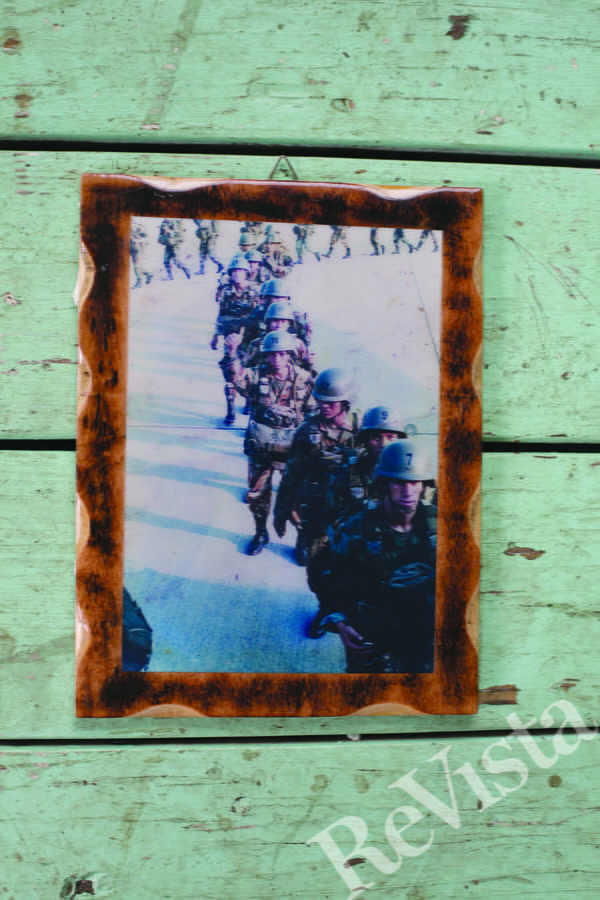

A photograph of a combat unit featuring Carlos Molina is prominently displayed on the wall in his home.

During the wartime a quarter of El Salvador’s population had fled the violence. The majority sought safe harbor in the United States but were denied refugee status because of U.S. policies that supported and fueled the conflict. As unacknowledged casualties of the turmoil, many were forced to live undocumented, the truth of their trauma repressed once again.

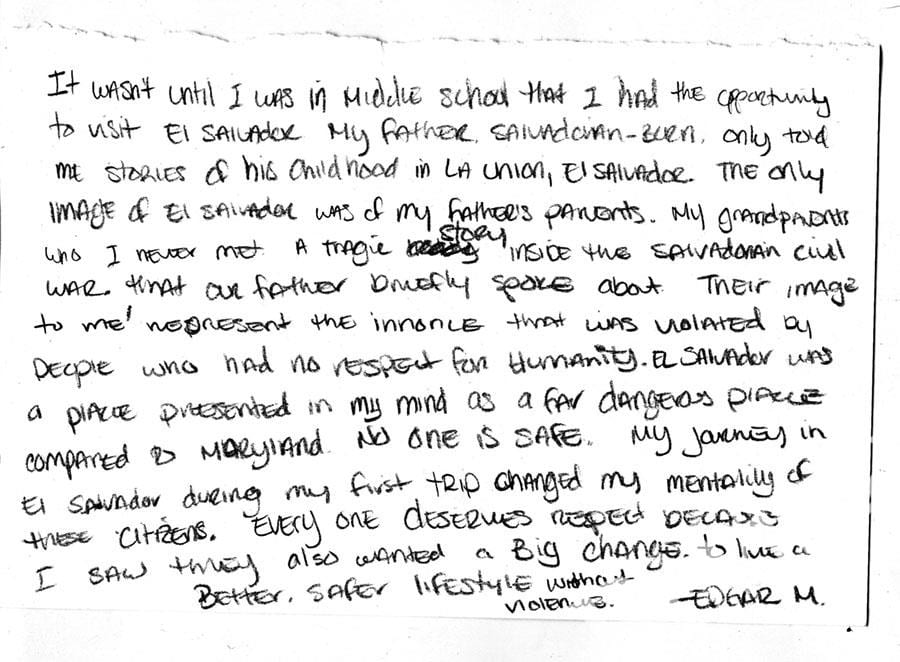

Edgar M. from La Unión, El Salvador, recalls in a letter how he had finally returned to El Salvador in middle school and wishes a better lifestyle without violence for his fellow Salvadorans.

The Salvadoran diaspora is a population perched between two countries. They live in the shadows in the United States but are unable to return to their home country now overrun by gang violence. Left in limbo, they look for El Salvador through the creative acts of ordinary life. Painted volcanoes mimic the landscape they left; food is a means of communicating culture and images are a way of holding close what is far away. Sentimentality is both the lifeboat and its leak.

“I miss this color,” Lorena said, holding up a painted wooden mango with the words El Salvador written on its base. She brought it close to her face and contemplated the speckled orange surface—as if it wasn’t right in front of her, as if it wasn’t really the color she missed at all. But through it she could grieve for all things lost, maybe even for the person who used to see those colors.

Richard Aparicio’s living room in the Washington D.C. area. Aparicio fled for the United States after fighting for the military. His mother, having her house bombed and her eyes infected from the smoke of burning bodies, was there waiting for him. He has seen deported twice. HIs son, Anthony Aparicio, said, “In my dreams I would see my dad and run to him. Then I would blink and he was gone. I would just lie on the ground and cry.”

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Caroline Lacey is a lens-based story teller living in Washington, DC. She has a Master’s in New Media Photojournalism from Corcoran College of Art+Design at George Washington University. Lacey recently won the PDNedu competition for photojournalism, the NPPA Bob East Scholarship and her video took first place in team multimedia at the Northern Short Course. Her work has been published in The Washington Post, Smithsonian Magazine Online, NPR, Washington Magazineand PDN.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

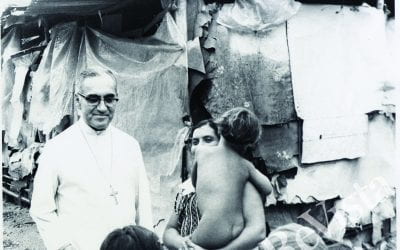

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…