A Seat at the Table

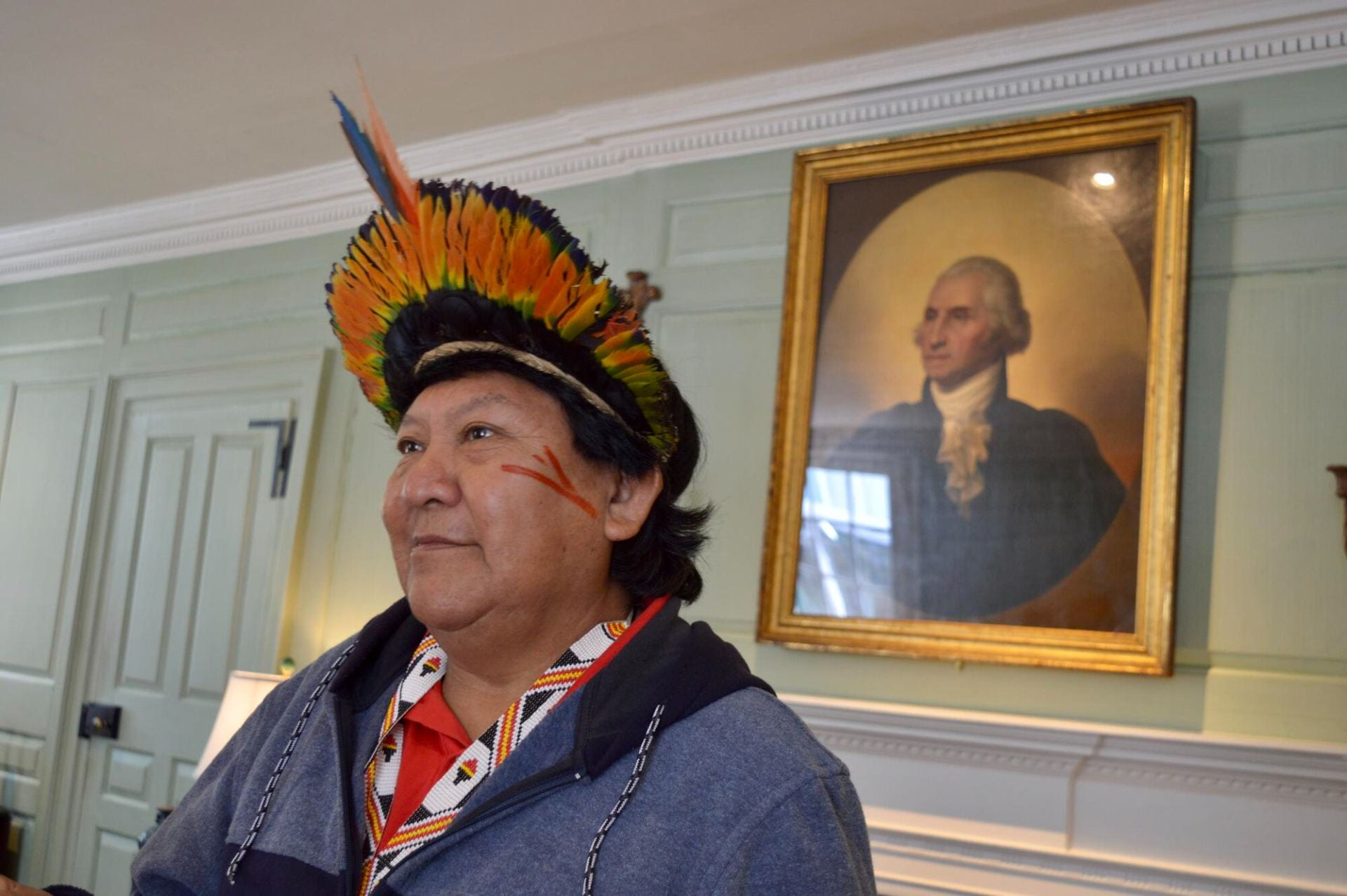

Five days with Davi Kopenawa

Photos by Dani Perez

About a year ago, a foreign visitor to Harvard gifted me with an odd realization. It doesn’t seem as something intentionally taught, but it may have been—it is impossible to know someone else’s intentions. What I know is that his spatial and cosmological imagination grew inside of me during his stay here, when I was designated to accompany him. On a daily basis, I still find myself seeing the world on his terms, acknowledging that though I am constantly guided by the concreteness of traffic lights, schedules, doors and other signs of built landscapes, the ground where I stand is actually a forest—only a different, severely modified one.

Born in 1956, Indigenous activist Davi Kopenawa Yanomami is a shaman and the prime spokesperson of the Yanomami and Ye’kwana people, an indigenous society of hunter gatherers located on the border between the Brazilian and Venezuelan Amazon rain forest. This relatively secluded green zone started being invaded during the 1940s and 1950s, when the evangelical Christian group New Tribes Mission attempted to convert its population, and the first federal government agents arrived. Their interventions brought lethal epidemics to the Yanomami, above all measles and the flu, taking the lives of Kopenawa’s closest family members. Since childhood, Kopenawa had to negotiate his existence with the “merchandise people,” as he would later term those foreigners who have built a project of a single humanity, or what academia calls modernity.

When we met at the airport, I was waiting to take him and his translator, anthropologist Helder Perri, directly to a symposium on the future of the Amazon rain forest sponsored by the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS). Kopenawa had been invited to deliver a speech to a crowded room of faculty and students, along with a few celebrities and investors interested in the forest’s courses of preservation and development of bioeconomies. Before getting onstage, he decorated his face with stripes of reddish vermilion annatto dye, used to obtain courage and strength, and put on a feathered headdress, one of the most valuable ornaments of his society, comparable to a jewel. Shifting to Portuguese whenever there wasn’t a compatible expression in his own language, he talked to the audience primarily in Yanomami.

Kopenawa has now returned to his home at the foot of the Watoriki (“Wind Mountain”), on the left bank of the Demini River. As I write, about 20,000 gold miners threaten one of Brazil’s largest indigenous reserves. Frequently armed, these men pollute fresh water with mercury, a contrasting substance, to find gold nuggets more easily. Their presence also brings new waves of diseases, such as Covid-19—the pandemic has already killed four Yanomami and there are 95 more confirmed cases among them. Kopenawa’s son, Dario Kopenawa, has been leading a global campaign, #minersoutcovidout, to demand authorities, especially Brazil’s federal government, to take judicial and military measures to protect their reserve. On that day in Harvard, his speech focused on the expulsion of these invaders.

Predicting the outcomes of President Jair Bolsonaro’s anti-indigenous politics, the elder Kopenawa made sure to warn the public about a codependency between climate crisis and the Amazon rain forest preservation. “With these people digging the ground,” he pointed out, “we are not going to live well, and neither will you.” Since Bolsonaro assumed the presidency, openly encouraging industrial ranching and land-grabbers in the Amazon, deforestation has skyrocketed. Decades of institutional work towards indigenous rights were dismantled through budget and personnel cuts, turning an already insufficient support into a regime of institutional inanition. Kopenawa also mentioned the deficiency of federal indigenous health structure—a demand that gains gravity when recontextualized in the current collapse of northern Brazil’s public health system during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“We need to call a global meeting to stop nature destroyers, so that they stop deforesting, destroying the soil, tearing Earth into pieces, weakening rivers,” he proposed during an ensuing panel with journalist Eliane Brum, former Minister of Environment of Colombia Luis Gilberto Murillo and theologian Augusto Zampini. Struggling to make his speech as coherent in Portuguese as it is in Yanomami, his affirmation may have come across as moving and somewhat naive to an academic public; it might have also been framed in a comparison to already existing initiatives in Western society, such as the United Nations Climate Change Conference. Thinking about his trajectory as an activist, I believe that what Kopenawa entailed in his talk—as he does with his presence in western society—was actually the complexity of sitting at the same table, a political challenge normally more performed than actually done.

After leaving his community at a very young age, Kopenawa saw himself reduced to a servile status in the city of Boa Vista, in northern Brazil. He learned Portuguese while recovering from malaria in a hospital, an ability that later would guarantee him a position at the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI). During a humanitarian mission, he became engaged to Fatima, and after the marriage, went back living with the Yanomami, later being initiated as a shaman. Throughout the 1970s, a federal project coordinated by the military dictatorship set out to build the Perimetral Norte railroad, cutting through Yanomami land and committing several human rights crimes in the process. Kopenawa became a political leader during this period. A decade later, gold mining invasions intensified and never fully stopped. It was only in 1992 that the Yanomami reserve, Brazil’s most extensive indigenous land, was formally approved.

One of Kopenawa’s most important political tools is his understanding of how he is listened to. He has passed through a lifetime of radical shifts that have taught him to skillfully advocate not only for his people, but for possibilities of new collectivities, more aware of the violence that crosses among many different groups and rests on the belief of a division between culture and nature. Being a representative of a world that our world perceives as being already transcended, his efforts are not only to make the napë (a word used to describe non-indigenous people that means “outsider, enemy”) reflect upon their ecological ignorance and colonial deafness, but also to preserve his own right to make a different world, in which space, time and being have other premises. A world that is actually capable of sustaining vitality.

Shortly after his presentation, we walked through Harvard Yard with other guests on our way to a restaurant. Sited on traditional territory of the Massachusett people, the first university in the New World struggled to keep its doors open soon after its foundation. At the time, the English Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England (SPGNE) granted funds that saved Harvard financially by sponsoring what came to be the Indian College (1640-93). This school hosted indigenous people and colonists with the promise that they would proselytize their home communities with the Gospel in exchange. As we crossed Quincy Street, Kopenawa pointed to the asphalt and told me that there was a lethal smoke coming out of it, but that we couldn’t sense it anymore. The Yanomami have associated the smoke from fossil fuels and the contact with industrial objects to epidemics, characterizing it as xawara, “smoke disease.”

I often tried to imagine how our society was perceived by his curious mind during the time I spent with him. I believed to know a little about the way he thought. Five years ago, I read his book, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, and was deeply changed by the it. A milestone in the human sciences, the book combines Kopenawa’s first-person life testimony with an account of his initiation as a shaman, followed by a critique of our current political economy of nature. Anthropologists Claude Lévi-Strauss and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro were among the enthusiastic readers of the work, mediated by the translation of French anthropologist Bruce Albert. Albert, who is also the book’s co-author, has been working with the Yanomami since the late 1970s, being an active part of their political struggle to have their territory recognized. Together, they have established an ethnographical pact in which the recording conversations between them in Yanomami were written in Kopenawa’s first-person voice, but edited in four hands.

The Falling Sky made Kopenawa an author and Yanomami shamanic philosophy more accessible to non-indigenous people. Viveiros de Castro classified the work as a “conterantropological” text, in which the reader is transported to a cosmovision that invites him or her to envision the forest in an enchanted perspective—one that is critically acute towards us. Written as an open letter to humanity, the book constantly reminds the reader how our world’s reasoning fails to properly understand the riches of difference. This transcultural translation is made through generous and lively writing, through which Kopenawa is able to invite the reader to be an ally of his people’s cosmovision, understanding his mode of being and the damages done by ours.

In Boston, our agenda included political meetings at the Massachusetts State House, mobilizations with the Brazilian community, as well as a stop at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum. The site is part of the Emerald Necklace, a network of parks and parkways laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted for the Boston Parks Department between 1878 and 1892. The Arboretum consists on a worldwide collection of trees, some especially brought during expeditions abroad. To Kopenawa, the idea of enclosing green areas in cities was problematic. After receiving an introduction on the park’s history, he asked the presenter why was it so small. Why wasn’t the whole city green? As we wander through the woods, Davi imitated birds, enraptured by the landscape. After more than three months of traveling and trying to make his words listened to, he was tired. “You see? This is colorful, this is alive,” he told me.

Back home, Kopenawa holds a position of intellectual authority. The codes of Yanomami sociopolitical dynamics are, however, dissimilar. In the practice of hereamuu speeches, the pata thë pë, meaning both “greatmen” or “elder men,” talk during dawn in order for their words not to fall into oblivion. This exercise is performed by shamans, who have access to the forest’s “images,” representatives of its forces and beings. Shamans are trained to heal their people by maintaining good relations with other species, receiving information about their images through dreaming. They keep the sky from falling.

Kopenawa’s political voice demands a hard acknowledgement, one that tells us that a position of unprivileged interlocution still holds a legitimate source of knowledge, as well as a much-needed contrast and critique of western thought. His contribution as a humanist is to try to make alliances with a society that excels in diminishing and appropriating his knowledges, including the forms in which his culture communicates with what we tend to call the non-human—that is, other species that, because and when entangled, make human life possible. There are 30 million species living in the Amazon besides the homo sapiens, and each of them lives with a different consciousness, each building a piece of a large chain of vital force that includes us.

A forest has many perspectives—it is an intertwined, vital collective of beings. For the Yanomami, this means diplomacy between humans and non-humans in order to sustain the sky. Kopanawa’s proposal of demanding real discussions about how to manage climate crisis seems to wisely touch a political problem of legitimacy between indigenous and non-indigenous cosmovisions. But it also entails what some scientists have called the world’s sixth extinction: to truly sit at the same table means to do it both between human and non-human beings, considering each of their places.

“The sun is rising,” Kopenawa told me on our last day together, after making fun of my habit of writing down words he tried to teach me, telling me that priests did the same thing. When reamu, parties in which different indigenous groups visit each other, are about to end, that is the statement which signals the visitors’ departure. After saying goodbye, I crossed over to a park in front of the hotel, shifting from an enclosed environment into one where I was able to see our planet’s shared sky. Step by step, learning how to touch the grass.

Spring/Summer 2020, Volume XIX, Number 3

Ana Laura Malmaceda is a writer and Ph.D. student in Romance Languages at Harvard University, where she studies ecological thinking. She holds a master’s degree in Brazilian Studies at the University of Lisbon (2017). E-mail: boenomalmaceda@g.harvard.edu.

Related Articles

Circuits of Glass

In 1909, Emilia Snethlage, a German ornithologist working for the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, arrived at the Curuá River in the eastern Brazilian Amazon. Just five years earlier, Snethlage (1868-1929) had received a Ph.D. from Freiburg University at a time when women…

Learning to Heal in an Amazonian Capital

It’s my 37th birthday, and I’m seventy days into social isolation in my hometown. Being from Belém has gifted me with a taste for the wonders of brega popular music, a knowledge of traditional herbal baths and an ability to cope with extreme heat and humidity…

Latin American Soldiers

John R. Bawden’s Latin American Soldiers: Armed Forces in the Region’s History introduces readers to the study of Latin American’s Armed Forces., Bawden examines warfare and military traditions in four different countries (Mexico, Cuba, Brazil and Chile)…