After more than a hundred days of quarantine, the Peruvian government said it would restrict isolation only to hot spots. Nevertheless, borders are still closed, deaths have not stopped, and the inequality gap continues to grow. Peru is my home. I was born and raised in Lima, and I came to the United States. as a college student last year. When schools closed, I was unable to go back home because air travel had ceased. From Brown University’s campus, I followed everything happening in Latin America, and as someone with Indigenous heritage as well, the current situation of Native communities concerns me immensely.

On July 2, Indigenous leader Santiago Manuin died after being transferred to Chiclayo city from his native Amazonas, where he was unable to get the appropriate medical attention. As a result, the Indigenous people of Loreto issued an ultimatum to the government, that if no immediate Covid-19 mitigation plan specific to the region is provided, they would take absolute control over oil lots and stop any kind of extractive activity in the region.

For centuries, Indigenous people from Peru have been loyal guardians of their communities and territories against oil, wood, mining extraction and exploitation activities, as well as many other industries that endanger their wellbeing. It is in this context that coronavirus becomes a new enemy that threatens the survival of these ancient cultures.

On March 13, the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin (COICA) addressed all member countries to take sanitary measures and to elaborate contingency plans in the context of the current situation of Indigenous peoples. However, it only took a week until the first positive case of coronavirus was diagnosed in the Peruvian Amazonian rainforest. Since then, the infection rate has continued to grow exponentially.

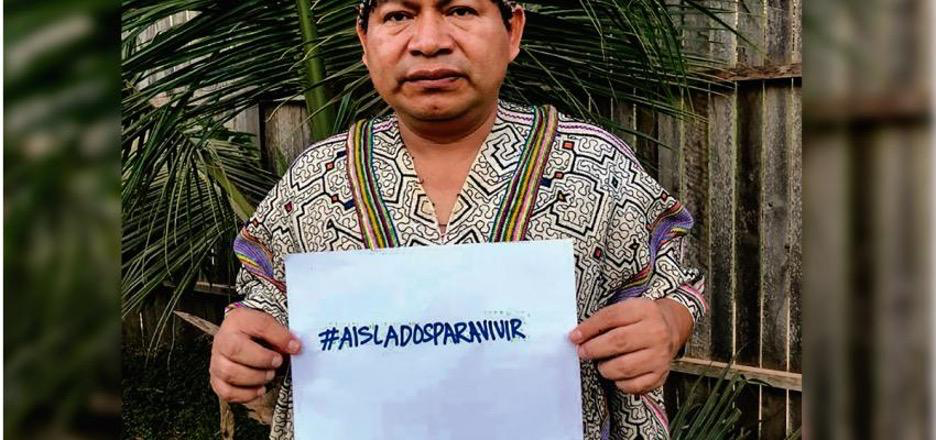

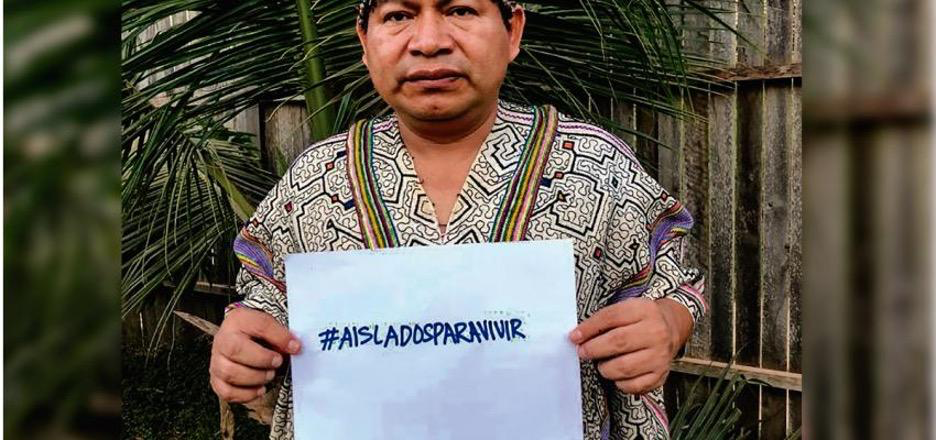

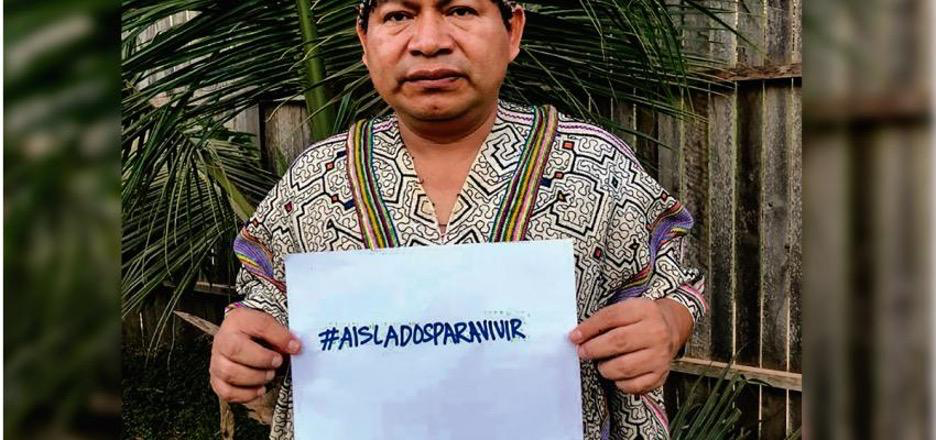

Forced to use banana leaves as masks, Indigenous Peruvians face a critical situation. In April, the leader or “Apu” of the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP) and my friend, Apu Lizardo Cauper, filed a report at the United Nations for the ethnocide that could happen if the effects of the pandemic are not mitigated on time.

Collective Memory: Past Pandemics

The continuous destruction of Native populations is a common denominator in the collective memories of all Indigenous peoples. Diseases such as the bubonic plague, smallpox and measles decimated the Indigenous population. As the philosopher Steven T. Katz states, this can be considered one of the major cultural and demographic disasters of human history.

When referring to the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic in Native communities, we make allusion to virgin soil epidemics. This term refers to pandemics in which populations at risk have no previous exposure to similar diseases and are therefore immunologically defenseless.

When Spanish settlers arrived in the Tahuantinsuyo Incan Empire, the Peruvian Indigenous population was reduced by an estimated 15 million in only 88 years due to a combination of diseases and inhumane life conditions. Oral tradition suggests that outbreaks of various illnesses caused severe havoc in the local population, but data is unavailable, making it impossible to determine the magnitude of the damages. The only known fact is that these communities were able to survive these pandemics through rondas campesinas, autonomous peasant patrols in rural Peru, and the use of traditional medicine, especially for patients with mild symptoms, since the majority has no easy access to a healthcare center.

Lack of Access to Basic Services

Currently, 55 Aboriginal communities live in Peru, with 51 are located in the Amazonian rainforest. Since time immemorial, these communities have fought for access to basic services like health and education, while they continue the fight for their conservation of their environment and home. The Indigenous population represents less than 10% of the local population. Nevertheless, they represent almost 20% of extreme poverty of the country, with 2.7 times more than the rest of the region.

Surprisingly, 21% of the Peruvian territory is part of mining concessions. In the Amazon, 75% belongs to oil and gas concessions. The local headquarters of these companies are equipped with the latest technology, while according to the 2017 National Census , 88.5% of Indigenous Amazonian communities do not have access to drinking water and only 7% have drainage at home. The situation is as concerning in terms of education. Only 2 to 5% of Indigenous students have achieved the expected literacy capacities in their native languages.

There is still no official record about the number of infected citizens and deaths in Indigenous communities, since the access to statistics and reports about the scope of the Peruvian healthcare system in the rainforest is very limited. While the Peruvian Ministry of Health estimates that the number of Indigenous people infected does not exceed 3,000, community leaders say that more than 10,000 Native citizens have been infected.

Zero Patient

The first positive case of coronavirus in Indigenous Peru was on March 19, when Apu Aurelio Chino, the leader of the Indigenous Quechua Federation of Pastaza, was diagnosed with the virus. He probably got the disease during his trip to the Netherlands, where he was filing a claim against the oil company Pluspetrol for the pollution of Indigenous territories. On his return to Peru, the Ministry of Health was conducting rapid testing for passengers with fever. However, because he was asymptomatic, he was not prevented from continuing his journey to the Amazon. However, he decided on his own to self-quarantine and isolate from his community for prevention. Days after his arrival, a press conference was held to make public that Apu Aurelio Chino was infected with the virus. Subsequently, he received false accusations of negligence that led to serious threats against his life.

The Triple Border

Stretching through Peru, Colombia and Brazil, this area is one of the major infection routes through the Amazon River. The river provides one of the main means of transport, supplying and food and medicine to the area. Even patients are transported on the river. One of the communities most affected by this route of infection is that of the Ticuna of Bellavista de Callaru, where only one medical center is available without medicine nor equipment and only an obstetrician for more than 3,000 habitants. Even since early May, this community already had an infection rate of 70% and dozens of suspicious cases of Covid-19. Another vivid example is the Shipibo town of Caimito that, to date, has more than 80% of its habitants infected with the virus. There are no doctors and only one nurse for 1,000 people.

The situation is even more complicated now for non-contacted populations. In the Peruvian-Brazilian border in Vale do Javari, approximately 8,000 Indigenous have never had any contact with other civilizations in the past. According to the World Health Organization, the situation of this region is extremely concerning, since this place is home to the largest number of uncontacted communities in the world and these citizens have never had exposure to foreign diseases.

Irremediable Loses

For many Indigenous cultures, the knowledge of old people is invaluable. Elders are considered masters and are the guardians of culture, knowledge and a symbol of leadership. Coronavirus is a threat to thousands of experienced representatives and Apus that have fought for years to elaborate strategies that would benefit all their communities. It is in these conditions that the president of the Federation of Ticuna Native and Yagua from Low Amazon Communities, Apu Humberto Chota, died July 7 due to lack of access to health services.

In view of the latent extinction risk of communities because of the virus’ rapid expansion, Cauper, the leader mentioned above, filed a complaint to the United Nations and the Organization of American States against the Peruvian government regarding the risk of a possible ethnocide. The report details the consequences of the lack of state action, as well as lack of access to education and health, accentuating malnutrition, poverty and mortality rate.

State Actions

In the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government debates if providing more protection to Aboriginal communities or benefiting the national economy. Cauper asked Congress to reevaluate the law Nº 28736, Law for the Protection of Indigenous and Aboriginal People in Situation of Isolation and Initial Contact, best known as law PIACI. This law imposed certain limitations for the exploitation of Indigenous reserves, but extractive activities are still allowed in some fields. The final decision of the Congress is still to be defined.

After three months of national lockdown and a constant fight by Indigenous leaders, the Peruvian president Martín Vizcarra visited the Indigenous community El Pilar and reiterated his willingness to send help to the most recondite areas of rural Peru. The government created the COVID-Indigenous Command in Loreto with a budget of 88 million Soles, US$25 million and inaugurated the Intervention Plan of the Health Minister for Indigenous Communities and Rural Human Settlements of the Amazonian Rainforest to confront the Covid-19 emergency. Nevertheless, weeks have passed since the creation of this contingency plan and there still is no official record of the number of cases or deaths due to bureaucratic barriers and the lack of constant access to health services in the area. The original plan was purely preventive to avoid the illness to reach the rainforest. But the virus is already in the Peruvian Amazon and this plan becomes more and more disconnected from reality.

In contrast, the U.S. embassy has directed US$3 million to mitigate the effects of the pandemic in Indigenous communities. This help includes the creation of two mobile hospitals to help habitants of rural areas.

Uncertain Future

The Indigenous economy depends mostly on the production and distribution of local products, as well as tourism. These two industries have been seriously compromised by the lockdown and there have been extreme changes in the income sources of Native communities. These transportation and logistics restrictions due to the pandemic have interrupted the production cycle, provoking a lack of food and health provisions in these regions.

It is urgent to research, report, document and analyze the impact of coronavirus in Native populations to create effective mitigation and prevention politics. The limited historical state presence in the region exacerbates the vulnerability of these communities and puts in risk rich cultures that are vital agents for the protection of our Peruvian diversity, innovation and identity.

El Coronavirus y la desigualdad

La lucha de los pueblos indígenas peruanos

Por Valerie Aguilar Dellisanti

Después de más de 100 días de cuarentena, el gobierno peruano anunció su fin para dar paso a un aislamiento focalizado. Sin embargo, las fronteras siguen cerradas, las muertes no cesan y la brecha de desigualdad continúa creciendo. El Perú es mi hogar. Yo nací y crecí en Lima, y vine a los Estados Unidos como estudiante universitaria el año pasado, por lo que no pude regresar a casa cuando las universidades cerraron sus locales. Desde el campus de la Universidad de Brown, sigo a detalle todo lo que pasa en Latinoamérica, y como alguien que tiene ascendencia indigena también, la situación de las comunidades nativas me preocupa inmensamente.

Este pasado dos de julio, el líder indígena, Santiago Manuin, falleció luego de haber sido trasladado de emergencia a la ciudad de Chiclayo desde su natal Amazonas, donde no pudo recibir la atención médica adecuada. Como resultado, los pobladores indígenas de Loreto dieron un ultimátum al gobierno que de no efectuarse un plan de mitigación inmediato de Covid-19 que sea específica para la región, tomarían control absoluto de los lotes petroleros y evitarían cualquier actividad extractiva en la región.

Por siglos, los pueblos indígenas del Perú han sido fieles protectores de sus comunidades y territorios frente a actividades de extracción y explotación petrolera, maderera, minera, entre muchas otras industrias que ponen en peligro su bienestar. Es en este contexto que el coronavirus se convierte en un nuevo enemigo que amenaza la supervivencia de estas culturas milenarias.

El 13 de marzo, la Coordinadora de las Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazónica (COICA) se dirigió a los países miembros para tomar medidas sanitarias y elaborar un plan de contingencia de acuerdo a la situación actual de los pueblos nativos. Sin embargo, solo pasó una semana hasta que el primer caso positivo de coronavirus fue diagnosticado en el Amazonas peruano. Desde entonces, la tasa de contagios no ha dejado de crecer exponencialmente.

Obligados a usar hojas del árbol de plátano como mascarillas, los indígenas peruanos se encuentran en una situación crítica. En abril, el líder o“Apu” de la Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP) y amigo mío, Apu Lizardo Cauper, hizo una denuncia ante las Naciones Unidas por el etnocidio que puede ocurrir si es que no se llega a mitigar el efecto de la pandemia a tiempo.

MEMORIA COLECTIVA: PANDEMIAS EN EL PASADO

La destrucción continua de la población nativa es un común denominador en la memoria colectiva de todos los pueblos indígenas. Enfermedades, como la plaga bubónica, varicela y sarampión, causaron la extrema reducción de la población indígena, y como bien describe el filósofo Steven T. Katz, podría ser considerado como uno de los mayores desastres demográficos y culturales de la historia.

Cuando se habla de los efectos de la pandemia del Covid-19 en comunidades nativas, hablamos de una epidemia en suelo virgen. Este término se refiere a pandemias en las que la población en riesgo no tiene previa exposición ni contacto con previas enfermedades similares y por ello son inmunológicamente indefensos.

Se estima que luego de la llegada de los colonos españoles al Imperio Inca del Tahuantinsuyo, la población indígena peruana se redujo por 15 millones en solo 88 años debido a una combinación de enfermedades y condiciones de vida inhumanas. La tradición oral cuenta que brotes de distintas enfermedades causaron estragos severos en la población, pero no existe data exacta y es imposible determinar la magnitud de los daños. Lo que sí se sabe es que las comunidades han podido sobrevivir estas pandemias a través de rondas o patrullas campesinas para la protección de sus territorios y el uso de medicina tradicional, especialmente para los pacientes con síntomas más leves, pues la mayoría no tiene acceso a un centro de salud cercano.

FALTA DE ACCESO A SERVICIOS BÁSICOS

Actualmente hay 55 pueblos originarios del Perú y 51 se encuentran en la Amazonía. Desde tiempos inmemorables, estas comunidades han batallado por el acceso a servicios básicos como salud y educación, mientras también siguen la lucha por la conservación de su ambiente y hogar. La población indígena representa menos del 10% de la población local. Sin embargo, ellos representan casi el 20% de la pobreza extrema del país, siendo 2.7 veces mayor que en el resto de la región.

El 21% del Perú es parte de concesiones mineras y en lo que respecta al Amazonas, el 75% pertenece a concesiones de petróleo y gas. Las centrales locales de estas empresas cuentan con tecnologías de última generación, mientras que, según el Censo Nacional del 2017, el 88.5% de los pueblos indígenas amazónicos no tienen acceso a agua potable y solo 7% tiene desagüe en casa. En cuanto a educación, la situación es igual de crítica. Solo entre el 2 y 5% de estudiantes indígenas tienen las capacidades lectoras esperadas en sus idiomas natales.

Aún no existe ningún registro oficial del número de contagiados ni fallecidos en comunidades indígenas, pues el acceso a estadísticas y reportes sobre el alcance del sistema de salud peruano en la selva es muy limitado. Mientras que el Ministerio de Salud peruano estima que el número de indígenas infectados no sobrepasa los 3.000, los líderes de las comunidades aseguran que hay más de 10.000 nativos contagiados.

PACIENTE CERO

A pesar de no conocerse exactamente el alcance del virus en comunidades indígenas, se sabe que el primer caso de coronavirus apareció en Perú nativo el 19 de marzo, cuando Apu Aurelio Chino, el líder de la Federación Indígena Quechua del Pastaza dio positivo. Contrajo posiblemente el virus en su viaje a los Países Bajos, donde se encontraba para hacer una denuncia a la empresa petrolera transnacional Pluspetrol por la contaminación de sus territorios. En su retorno a Perú, el Ministerio de Salud condujo pruebas rápidas para los pasajeros que presentaban fiebre, y por ser asintomático, no se le impidió continuar con su viaje. Sin embargo, él decidió ponerse en cuarentena por su propia cuenta y aislarse de su comunidad por prevención. Días después de su llegada, hubo una conferencia de prensa donde se reveló públicamente que el señor Aurelio Chino estaba infectado con el virus. Subsecuentemente, recibió acusaciones falsas de negligencia que llevaron a amenazas graves contra su persona.

LA TRIPLE FRONTERA

Compuesta por Perú, Colombia y Brasil, esta zona es una de las mayores rutas de contagio a través del río Amazonas. Este facilita uno de los principales medios locales de transporte y es mediante este río que se suministran alimentos, medicinas e incluso se trasladan a pacientes. Uno de los casos más impactantes es el de los Ticunas de la comunidad Bellavista de Callarú, donde solo existe una posta sin medicinas ni equipamiento en la que un único obstetra atiende a más de 3.000 pobladores. A inicios del mes de mayo ya contaba con una tasa de infección de 70% y decenas de casos sospechosos de Covid-19. Otro vívido ejemplo es el pueblo Shipibo Caimito que a la fecha ya cuenta con más de 80% de habitantes infectados y solo hay un enfermero para atender a casi 1.000 personas.

La situación se complica aún más para las poblaciones no contactadas. En la frontera con Brasil en Vale do Javari, hay cerca de 8.000 indígenas que jamás han tenido contacto con otras civilizaciones. De acuerdo con la Organización Panamericana de la Salud, el estado de esta región es extremadamente preocupante pues este lugar es el hogar del mayor número de pueblos no contactados del mundo y estos habitantes nunca han tenido exposición a enfermedades extranjeras.

PÉRDIDAS IRREMEDIABLES

Para muchísimas culturas indígenas, la sabiduría de los ancianos es invaluable. Los adultos mayores son considerados maestros y son los transmisores de cultura, conocimiento y un símbolo de liderazgo. El coronavirus es una amenaza a miles de experimentados representantes y Apus que han luchado por años por elaborar estrategias que beneficien a todas sus comunidades. En estas precarias condiciones, el presidente de la Federación de Comunidades Nativas Ticunas y Yagua del Bajo Amazonas (FECONATIYA), Apu Humberto Chota, falleció el pasado siete de junio por la falta de acceso a servicios de salud.

En vista del latente peligro de extinción de estas comunidades por la rápida expansión del virus, Cauper, el líder mencionado arriba, denunció al gobierno peruano ante las Naciones Unidas (ONU) y la Organización de Estados Americanos (OEA) por el riesgo de un posible etnocidio. La denuncia detalla las consecuencias de la falta de acción estatal, tales como falta de acceso a educación y salud, acentuando la desnutrición, pobreza y tasa de mortalidad.

ACCIONES DEL ESTADO

En medio de la pandemia del Covid-19, el gobierno debate si brindar más protección a los pueblos originarios o beneficiar a la economía nacional. Cauper demanda al congreso la reevaluación de la ley Nº 28736, Ley para la Protección de Pueblos Indígenas u Originarios en situación de Aislamiento y en situación de Contacto Inicial, más conocida como la ley PIACI. Esta ley impuso ciertas limitaciones a la explotación de reservas indígenas, pero aún permite la actividad extractiva en varios ámbitos. La decisión final del congreso está aún por definirse.

Después de tres meses de cuarentena a nivel nacional y de una constante lucha por parte de los líderes indígenas, el presidente peruano Martín Vizcarra visitó la comunidad indígena El Pilar y ratificó su voluntad de hacer llegar la ayuda a las áreas más recónditas del Perú. Se creó el Comando COVID-indígena en Loreto, y con un presupuesto de 88 millones de Soles, 25 millones de dólares estadounidenses, y se instauró el Plan de Intervención del Ministerio de Salud para Comunidades Indígenas y Centros Poblados Rurales de la Amazonía frente a la emergencia del COVID-19. No obstante, han pasado semanas desde la creación de este plan de emergencia y aún no hay registro oficial del número de infectados ni muertes por las barreras burocráticas y la falta de acceso constante a servicios de salud en la zona. El plan original era netamente preventivo para evitar que la enfermedad llegue a la selva. A pesar de ello, el virus está latente en el Amazonas peruano y este plan se vuelve cada vez más desconectado de la realidad.

A su vez, la embajada estadounidense destinó tres millones de dólares para mitigar los efectos de la pandemia en comunidades indígenas. Esta ayuda incluye la creación de dos hospitales móviles para ayudar a pobladores de zonas rurales.

FUTURO INCIERTO

La economía indígena, en su mayoría, depende altamente de la producción y venta de productos locales, así como del turismo. Estas dos industrias se han visto extremadamente afectadas por la cuarentena y ha causado grandes estragos en las fuentes de ingresos de las comunidades nativas. Las restricciones de transporte y logística debido a la pandemia han interrumpido el ciclo productivo y han generado adicionalmente una falta de insumos alimenticios y de salud en estas regiones.

Es urgente investigar, reportar, documentar y analizar el impacto del coronavirus en los pueblos oriundos para poder crear políticas de mitigación y prevención efectivas. La histórica limitada presencia estatal en la región exacerba la vulnerabilidad de estas comunidades y pone en riesgo culturas milenarias que son agentes vitales de la protección de nuestra diversidad, innovación e identidad peruana.

Uma Batalha de Duas Frentes

A luta de pessoas indígenas peruvias contra coronavirus e desigualdade

Por Valerie Aguilar Dellisanti e traduzido por Livia Gimenes

Depois de mais de cem dias de quarentena, o governo Peruviano anunciou que terminaria com o isolamento forçado. No entanto, as mortes nunca pararam e as desigualdades e o fosso de desigualdade continua a crescer. O Peru é a minha casa. Eu nasci e cresci em Lima e vim para os Estados Unidos como estudante de graduação ano passado. Quando as universidades fecharam, eu não pude retornar porque as fronteiras áreas tinham sido fechadas. Do campus da Brown University, eu acompanhei o que estava acontecendo na América Latina e como alguém com discentes Indígenas, a situação atual das comunidades Nativas me preocupa muito.

No dia 2 de Julho, o líder indígena, Santiago Manuin, morreu depois de ser transferido para Chicalayo city do Amazonas, a sua terra natal, porque não conseguiu atenção médica. O evento resultou num ultimato do povo Indígena de Loreto: se medidas não fossem tomadas, eles tomariam controle absoluto da produção de óleo e impediriam qualquer tipo de atividade de extrativismo na região.

Por séculos, os povos indígenas do Peru tem sido guardians leais das suas comunidades e territórios contra atividades extrativistas de óleo e mineração junto com outras indústrias que são um perigo para a sua saúde.Nesse contexto que o coronavírus se torna o novo inimigo que põem em xeque a sobrevivência desses povos ancestrais.

No dia 13 de Março, a Coordenadoria das Organizações Indígenas da Bacia Amazônica (COICA) pediu que para todos os países membros tomarem medidas sanitárias e elaborarem planos de contingência de acordo com a situação atual das populações indígenas. Entretanto, foi apenas necessário uma semana para que o primeiro caso positivo de coronavírus aparecesse na Amazônia Peruana. Desde de então, a taxa de infecção continua a crescer exponencialmente.

Sendo que ser forçados a usarem máscaras feitas de folhas de banana, a situação dos povos indígenas peruanos é crítica. Em Abril, o líder da Associação Interétnica para o Desenvolvimento da Floresta Tropical Peruana (AIDESEP), Apu Lizardo Cauper, emitiu um relatório para a ONU que alertava que um etnocídio poderia acontecer se os efeitos da pandemia não forem logo mitigados.

MEMORIA COLETIVA: O PASSADO DAS PANDEMIAS

A disseminação contínua de populações nativas é parte da memória coletiva de todas as populações indígenas. Doenças como, a peste bubônica, catapora, sarampo e outras, causam uma redução extrema das populações indígena e segundo o filósofo, Steven T. Katz, pode ser considerado um dos grandes desastres culturais e demográficos da historia da humanidade.

Historicamente, os povos indígenas peruanos foram vítimas de inúmeras pandemias que exterminaram grande parte da sua população. Pode se estimar que depois da chegada dos colonizadores espanhóis no império inca, os povos indígenas peruanos foram reduzidos para 15 milhões em apenas 88 anos por causa de uma combinação de doenças e condições de vida inhumanas. A tradição oral sugere que surtos de várias doenças causaram caos nas populações locais, no entanto, não se tem informação suficiente assim tornando praticamente impossível determinar a magnitude dos estragos. A única certeza é que essas comunidades foram capazes de sobreviver essas pandemias através das rondas campesinas, patrulhas autônomas de camponeses nas zonas rurais do Peru,e a medicina tradicional, especialmente em pacientes com sintomas leves, já que a maioria não tinha nenhum acesso fácil a saúde pública.

A FALTA DE ACCESO A BÁSICOS

Desigualdade Constante

Atualmente, existem 55 comunidades Aborígenes no Peru, das quais 51 são localizadas na floresta amazônica.Desde de sempre, estas comunidades lutam para ter acesso a serviços básicos como saúde e educação, enquanto continuam a lutar pela conservação do seu próprio ambiente e casa. As populações indígenas representam menos de 10% das populações locais. No entanto, elas representam quase 20% das população em pobreza extrema, mais do 2.7 vezes do que o resto da região.

Surpreendentemente, 21% do território peruano foi concedido para empresas usarem para a mineração e na Amazônia, 75% do território foi concedido para extração de óleo e gás. As sedes destas empresas são equipadas com tecnologia de ponta, enquanto, segundo o Censo Nacional de 2017, 88.5% das comunidades indígenas nas Amazônia não tem acesso a água potável e apenas 7% têm drenagem em suas casas. Quando se fala em educação, a situação também é alarmante. Apenas 2 a 5% dos estudantes indígenas atingem o nível de alfabetização esperado nas suas línguas nativas.

Ainda não se tem nenhum documento oficial sobre o número de infectados e mortos nas comunidades indígenas, já que o acesso a dados e relatórios sobre o alcance do sistema de saudade peruana na amazônia é muito limitado. Enquanto o Ministério da Saúde do Peru estima que o número de infectados nas comunidades indígenas não passa de 3.000, líderes das comunidades afirmam que já tiveram mais de 10.000 cidadãos nativos infectados.

Paciente Zero

Não se sabe o impacto exato do vírus nas comunidades nas comunidades indígenas, no entanto, se sabe que o primeiro caso positivo do coronavírus entre essas comunidades foi no dia 19 de Março, quando Apu Aurélio Chino, o líder da Federação Indígena Quechua de Pastaza foi diagnosticado com o vírus. Ele provavelmente contraiu a doença numa viagem a Holanda, onde ele estava preenchendo um relatório contra Pluspetrol, uma companhia de óleo que estava poluindo os seus territórios. No seu retorno ao Peru,o Ministério da Saúde estava realizando testes rápidos para passageiros com febre e porque ele era um caso assintomático, ele pode retornar normalmente. No entanto, ele decidiu se isolar e ficar em quarentena voluntária para proteger a sua comunidade. Dias depois da sua chegada, uma conferência com a imprensa foi realizada onde foi anunciado publicamente que Apu Aurelio Chino estava infectado. Por causa disso, ele recebeu acusações de negligência que resultaram em ameaças sérias à sua vida.

A Fronteira tripla

Composta pelo Peru, Colômbia e Brasil, esta é uma das maiores rotas de infecções através do Rio Amazonas. Ele facilita um dos principais meios de transporte e é através desse rio que comida e medicamentos e até pacientes são transportados. Um dos casos mais impactos é na comunidade de Ticuna de Bellavista de Callaru, onde se tem apenas um centro médico disponível onde não se tem remédios ou equipamentos e apenas um médico para mais de 3.000 moradores. Desde o começo de Maio, essa comunidade já teve um taxa de contaminação de 70% e dezenas de casos suspeitos de COVID-19. Um outro exemplo vivido é o caso da cidade de Shipibo de Caimito que, até hoje, mais de 80% dos seus moradores contraíram o vírus e há apenas uma enfermeira para 1.000 pessoas.

A situação é ainda mais complicado para povos isolados. Na fronteira entre o Peru e Brasil no Vale do Javari, há aproximadamente 8.000 povos indígenas que não tiveram contato com nenhuma outra civilização no passado. Segundo a Organização mundial da Saúde, a situação na região ainda é extremamente preocupante, já que é o lugar com a região com o maior número de povos isolados no mundo e esses povos não tiveram contato com nenhuma doença estrangeira.

Perdas irremediaveis

Para muitas culturas indígenas, o conhecimentos dos idosos é inestimável . Anciãos são considerados mestres e os guardiões da cultura, conhecimento e um símbolo de liderança. O Coronavírus é uma ameaça para centenas de representantes e Apus com experience que lutaram por anos para criar estratégias que beneficiam toda a sua comunidade. Nessas condições que o presidente da Federação de Nativos da Ticuna e Yagua das comunidades do Baixo Amazonas, Apu Humberto Chota, faleceu no dia 7 de Julho por causa da falta de acesso a serviços de saúde.

Por causa do risco latente de extinção dessas comunidades por causa da rápida expansão do vírus, o presidente da maior organização indígena peruana, AIDESP, Lizardo Cauper, preencheu uma reclamação para a Nações Unidas e para a Organização dos Estados Americanos contra o governo Peruano sobre o risco de um possível etnocídio. O relatório explica as consequência da falta de ações do estado e também da falta de acesso a educação e a saúde, destacando a má nutrição, pobreza e risco de mortalidade.

AÇÕES DO ESTADO

No meio da pandemia do COVID-19, o governo discute se deve prover mais proteção para comunidades Aborígenes ou beneficiar a economia nacional. Apu Lizardo Cauper demanda que o Congresso reavalie a lei Nº 28736, a Lei para a Proteção do Povo Indígena e Aborígene em situação de Isolamento e Contato Inicial, melhor conhecida como a lei PIACI. Essa lei impõe certas restrições na exploração de reservas indígenas, mas atividades extrativista ainda não permitidas em algumas áreas. A decisão final do Congresso ainda não foi tomada.

De outro lado, depois de três meses de um lockdown nacional e constante luta por líderes Indígenas, o Presidente do Peru Martin Vizcarra visitou a comunidade indígena de El Pilar e ratificou a sua vontade de mandar ajuda para as áreas mais recônditas do Peru rural. O governo criou o COVID- Comando Indígena in Loreto com um orçamento de 88 milhões soles, 25 milhões de dólares e inaugurou o Plano de Intervenção do Ministério da Saúde para as Comunidades Indígenas e Rurais da Floresta Amazônica devido a emergência do COVID-19. No entanto, semanas passaram desde da criação desse plano de contingência e não tem nenhum registro do número de casos ou mortes causados por causa barreiras burocráticas e falta de acesso constante a serviços da saúde na região. O plano original era puramente preventivo para evitar que a doença chegue à floresta tropical. Apesar disso, o vírus continua latente na Amazônia Peruana e esse plano se torna cada vez desconectado da realidade.

De outro lado, a embaixada dos Estados Unidos dirigiu tres milhoes de dolares para mitigar os efeitos da pandemia em comunidades indígenas. Isso possibilitou a criação de dois hospitais móveis para ajudar moradores de áreas rurais.

FUTURO INDEFINIDO

A economia indígena depende grande parte na produção e distribuição de produtos locais e no turismo. Ambas indústrias foram seriamente comprometidas por causa do lockdown e houveram alterações sérias nas fontes de renda das comunidades nativas. Essas restrições de transporte e logística devido a pandemia interromperam o ciclo de produção e geraram falta de comida e fornecimento de medicamentos e equipamento médico nessas regiões.

É urgente pesquisar, documentar, registrar e analisar o impacto do coronavírus em povos nativos para criar efeitos de mitigação e prevenção.A presença limitada do estado histórico na região exacerba a vulnerabilidade dessas comunidades e põe em risco culturas ricas que são agentes vitais para a proteção de nossa diversidade, inovação e identidade peruanas.

Valerie Aguilar Dellisanti is a Peruvian advocate for Indigenous Rights and a student at Brown University. She serves as the Managing Director of the Ministry of Production’s Covid-19 Project and a MIT COVID-19 Challenge Winner. Email: valerie_aguilar_dellisanti@brown.edu

Valerie Aguilar Dellisanti es activista peruana de derechos indígenas y estudiante de Brown University. Es la Managing Director del Proyecto COVID-19 del Ministerio de Producción y una de las ganadoras del MIT COVID-19 Challenge. Email: valerie_aguilar_dellisanti@brown.edu

Valerie Aguilar Dellisanti é uma ativista Peruana para direitos indígenas e uma estudante na Brown University. Ela é a Diretora Geral do COVID-19 Project do Ministério de Produção e a vencedora do MIT COVID-19 Challenge. Email: valerie_aguilar_dellisanti@brown.edu

Lívia Gimenes é uma estudante brasileira na Brown University e jornalista do Brown Daily Herald. Email: livia_gimenes@brown.ed

Related Articles

Masks: A Luxury Item in Haiti

English + Português

“Nurse Marie” tells her patients over and over again to keep their masks safe, clean, and sanitized. Masks are a luxury item in Haiti. “I always make it a priority here at the hospital…

A Nation at a Crossroads

Winds of change, fueled as much by politics as by the pandemic, framed the rise, campaign and inauguration of Gabriel Boric, 36, who took office March 11 as the youngest president in Chile’s…

The Tragedy of Covid-19 in Canaima, Venezuela

English + Español

Canaima National Park in southern Venezuela, studded with flat table-top mountains and spectacular waterfalls, has long been reliant on ecotourism to sustain its economy and the lives of…