African and Afro-Indian Rebel Leaders in Latin America

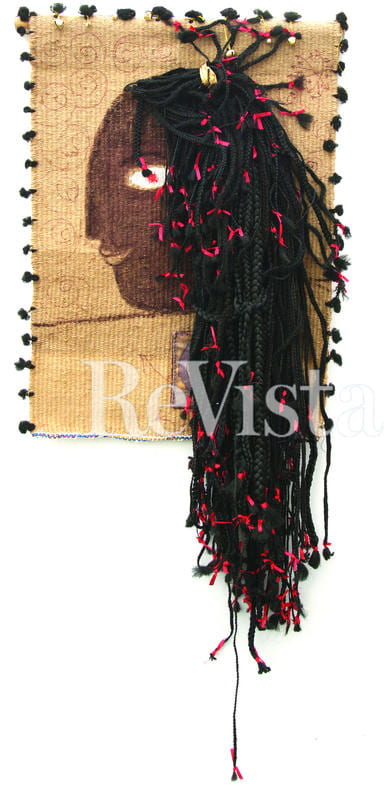

Con Tanta Arrogancia

On Christmas Day in the year 1521, and half a world away from home, a group of enslaved West African Muslim warriors led a slave revolt on the island of Hispaniola, a distant island across a vast ocean. The Wolof slaves had little chance of success, facing the long steel swords, lances, and guns of their Spanish captors. Their valiant, albeit desperate, revolt was quickly put down. Nevertheless, they unsettled their Iberian captors, whose quest for power and wealth stoked the fires of war on both sides of the Atlantic.

Spanish authorities, relying increasingly on Portuguese slave traffickers, soon passed a series of ordinances to limit the number of Muslim Africans taken to their colonies in the Americas. Many of these Africans were captives of war with military experience, and they were viewed as particularly dangerous. Still, the Spaniards’ insatiable desire for labor outweighed their fears, which were well-founded as enslaved Africans (Muslims and non-Muslims alike) continued to rebel. Over the next three centuries there would be hundreds of documented instances of African revolts in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of the Americas.

During the 16th century, Africans and their descendants outnumbered Iberians and their descendants in Mexico City, Lima and Salvador da Bahia—the three principal cities of colonial Latin America. Between the 16th and mid-19th centuries, more than ten million West and Central West Africans (with an additional 720,000 from Southeastern Africa) were forcibly taken to work on the plantations, gold and silver mines, and in the cities of Spanish and Portuguese colonists in the Americas. Resistance to slavery took place at the first point of contact in Africa and continued at sea and in the colonies in various ways such as feigning illness, poisoning masters, setting fire to crops, escaping and armed rebellions. Although many enslaved Africans and their descendants also assimilated into colonial societies, no one (colonists, servants or slaves) could escape the violence of slavery that permeated the Atlantic world, either as perpetrators, victims or witnesses.

Once they landed on American soil, some Africans escaped to join Native Americans. These Africans mixed with Taino and Arawak peoples in the Caribbean, and Wayuu, Caquetio, and Chocó, among other tribes, and their descendants, on the mainland. Many others escaped slavery by taking their own lives and “flying” back to Africa, rather than face the social death and brutality of slavery—or they ran away into the hinterland. The latter runaways, called “maroons”— a word that comes from the Spanish cimarrón (used to describe wild or escaped cattle)—fled into the forests, swamps, hills and mountains, where they entrenched themselves—and, from there, continued to wage war.

Among the most prominent maroon leaders of the Atlantic world was Benkos Biohó. Captured in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, in 1596, Biohó was shackled and shipped to the port of Cartagena. Within three years of his arrival to New Grenada (now Colombia), Biohó organized a slave revolt involving nearly three dozen people. The rebellion included his wife, Wiwa, and a grown daughter, Orika, among thir- ty others whom he led deep into the forest. There, they formed and defended one of the longest-lasting maroon settlements in the Americas, known as San Basilio de Palenque.

From Palenque at the base of the Montes de María, Biohó launched multiple attacks on Spanish colonists in Cartagena. The attacks went on for fourteen years, until 1613, when he agreed to a peace treaty with the Spaniards. By then Biohó had become known as “el rey del arcabuco,” “the king of the thick forest.” However, Biohó openly visited Cartagena under protection of the treaty, and he did so dressed in Spanish gentleman’s attire with sword and dagger at his side. But the audacity of a free African walking into the colonial stronghold con tanta arrogancia (“with such arrogance”), would only be tolerated for so long by the Spaniards.

Betrayed, Biohó was arrested on one of his visits and executed. But even in death Biohó would continue to inspire others to resist their enslavement, take up arms and follow his footsteps into the forest.

Maroon settlements and slave insurrections would haunt colonial authorities for generations to come. Over the next two hundred years, successive waves of maroons in New Grenada included many who took Biohó‘s name, or variations thereof, as a title. The name ‘Biohó’ had effectively become synonymous with African resistance, his story forming part of the collective memory of African and African-descended rebel leaders across Latin America. These gures included Gaspar Yanga, a contemporary of Biohó, who formed a powerful maroon settlement in the highlands near Veracruz, Mexico; the maroon Miguel, who escaped from the mines near Barquisimeto, Venezuela, and formed a free settlement made up of African slaves and enslaved Native Americans; Joseph Chatoyer of St. Vincent, a Garifuna (mixed African and Native American) leader who led a protracted war against colonists during the 18th century; Dutty Boukman, a contemporary of Chatoyer, who was an early leader of what became the Haitian Revolution; and Ganga Zumba, the son of an Angolan princess and the first leader of a massive maroon settlement Quilombo dos Palmares in Brazil.

To be sure, not all Africans were slaves and not all slaves were Africans. Iberians rst enslaved Native Americans, who fought back and proved difficult to keep alive and in bondage, as many died because of their lack of immunity to certain diseases (especially small pox), fought back, or escaped, being familiar with the terrain of their own land. In the complicated political conditions of the trans-atlantic slave trade and early colonial period, Africans and people of African descent sometimes even fought alongside Spaniards. People of African descent had been part of Christopher Columbus’ crew at the end of the 15th century—by which time sub-Saharan Africans had already become a presence in southern Iberia with the first African captives taken to Iberia as early as 1444.

The most famous African soldier fighting for Spanish interests was Juan Garrido, originally from West Africa, who fought on the side of Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortéz whose army invaded Mexico and lay siege on the Aztec capital at Tenochtitlan in 1519. But whether in the battles for domination over the Aztecs or in other colonizing efforts elsewhere in the Americas—including the Spanish conquest of Peru—Africans and people of African descent at times found themselves on the defensive, even stranded with Spaniards.

One such occasion took place in the spring of 1568. Eighteen months earlier, and some forty years before the English settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, soldiers of African descent were part of Spanish expeditionary forces in the Piedmont of North Carolina. The soldiers were left stranded—marooned—in the small forts they had built in the North Ameri- can southeast when Native Americans pushed back against Spanish incursions. Among these Spanish forts was San Juan, built next to Joara (Xuala), a large Native American settlement and regional chiefdom of Mississippian culture in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. In a coordinated attack in May 1568, Native Americans destroyed Fort San Juan along with four other small Spanish forts that had been built under the orders of Governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who wished to claim the interior of North America for Spain to establish an overland route to the silver mines near Zacatecas, Mexico (the colonists were more than two thousand miles off in their calculations).

Africans fighting alongside Spaniards, however, were a small number compared to those who fought against the Iberians. From the earliest moments of Iberian colonizing efforts in the Americas, Africans joined forces with Native Americans. If they had been successful in their Christmas day rebellion, the Wolof warriors might have joined Native Americans, as others did across the Caribbean. Among these rebels were Garifuna, West Africans who escaped from a slave shipwreck off the coast of St. Vincent in 1675 and who intermixed with Carib and Arawak peoples on the island. After a century of warfare and a series of forced migrations, the Garifuna people eventually settled in Central America after their greatest leader, Joseph Chatoyer, was killed in battle in 1796.

Rebellions in South America mirrored those across the Caribbean and North America. The largest maroon settlement in the Americas was formed in Brazil in 1604 in what is now the state of Alagoas, south of Recife. Called Quilombo dos Palmares, and founded by an African named Ganga Zumba in the Serra de Barriga, the settlement of Africans and Native Americans grew to more than 11,000 strong and lasted for nearly a century—that is, until its last leader, Zumbi (like Biohó) was betrayed and executed. Resistance to Portuguese forces continued well into the next century but it was Muslims in the area of Bahia that were at the forefront of a powerful series of revolts during the early 19th century.

Over the course of the transatlantic slave trade, Brazil received nearly four and half million Africans (some 40 percent of the total number of Africans taken out of the continent). Among these captives were at least 800,000 Muslims—an estimated twenty percent of Africans enslaved in the Americas. And nowhere was their presence more acutely felt than in Salvador da Bahia, culminating in the Malê revolt of 1835 (Muslims were called Malê in Bahia, derived from the word imale, a Yoruba Muslim).

Led by Muslim Yoruba and Hausa slaves, leaders of the revolt included Manoel Calafate, who recruited slaves on the eve of the attack, scheduled for Sunday, January 25. However, plans of the revolt were leaked and the rebels were forced to launch their attack a day earlier. Street fighting broke out and spilled into neighboring areas, including near the barracks. Under heavy fire, including multiple cavalry charges, the Iberians were able to contain the rebellion. In the aftermath, and fearing another Haiti—where slaves seized power and abolished slavery in 1804—colonial authorities executed nearly half a dozen leaders, sent others to prison and hard labor, and publicly flogged dozens of other black rebels; others were simply deported back to Africa. While Brazil ended the slave trade in 1851, it would take the country until 1888 to abolish slavery itself—the last place in the Americas to do so.

Cuba, like Brazil, witnessed slave revolts throughout this same time. By the early 19th century, Cuba had become the most productive sugar colony in the Caribbean and had a reputation as one of the most brutal plantation complexes. In the area of Matanzas, enslaved Africans with military experience organized a series of large-scale rebellions. Ten years before the Malê revolt in Brazil, and starting on June 15, 1825, about two hundred slaves participated in a coordinated revolt that spread to over two dozen plantations. Notably, the vast majority of the slave rebels, including leaders such as Pablo Gangá and Lorenzo Lucumí, were born in Africa. Even though the rebels originally came from different geographic regions and ethnic backgrounds in Africa, they were joined by their common desire to be free.

Slave rebellions were also part of the African diaspora on the Andean side of South America. In Peru, where more than 100,000 Africans were imported, slaves cleared land, laid the streets, and carried supplies, among others duties; mortality rates among enslaved African-descended populations working the silver mines in the Andes were especially high.

As elsewhere in Latin America, Africans and their descendants in Peru resisted slavery in a number of ways—most commonly, by running away. In 1595, for instance, one Domingo Biafara took ight for weeks at a time; in 1645, Francisca Criolla was sold “without guarantee” because of her reputation for escaping. The official punishment for running away changed over time, but starting off with 100 lashes was not uncommon. One group of slaves destined for Lima was shipwrecked off the coast of Guayaquil. Many of those who survived would join Native Americans to form what became the largest maroon society on the western coast of South America, in what is today Esmeraldas. A painting by Adrián Sánchez Galque in 1599 powerfully depicts one of its Afro-Indian leaders, Don Francisco (de) Arobe, anked by his two sons, depicting a mix of Spanish, African and Native American influences.

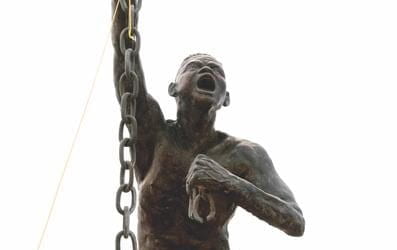

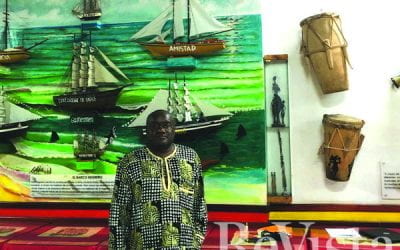

Today, African and Afro-Indian rebels are remembered to varying extents in Latin America. There are reconstructed images, such as statues of gures such as Biohó in Colombia or Zumbi in Brazil. In each of those countries these gures are considered national folk heroes, especially among Afro-Colombians and Afro-Brazilians, respectively. In Peru, however, most citizens are unaware of black resistance to slavery because the history of its African-descended population is little known (despite such eminent religious figures, most strikingly, San Marin de Porres, the son of an Afrodescendant mother and a Spanish father). Meanwhile Garifunas in Honduras, Belize, Guatemala and Nicaragua, struggle to have a voice in their respective countries, where they remain segregated from most national histories. Nevertheless, their history is performed through dance and music—as is the case across much of Afro-Latin America (carnival being an expression of this across Latin America). For instance, the battles waged by Garifunas against colonists are performed today as yankunu by men in which they depict the ways their ancestors launched attacks on colonists. Garifuna women sing and dance other stories in punta, which like yankunu is accompanied by multiple drums.

To the extent that African and Afrodescendant rebels have a history, it is reconstruction upon reconstruction. Layers of history and legend intermixing. What comes through when panning out across the whole of Latin America and over the course of several centuries, however, is the ongoing resistance of men and women born in Africa or descended from those who originally came from Africa.

Winter 2018, Volume XVII, Number 2

Omar H. Ali is Dean of Lloyd International Honors College and Professor of Global and Comparative African Diaspora History at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. A former DRCLAS Library Scholar, he was selected as The Carnegie Foundation North Carolina Professor of the Year. His latest book is Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Related Articles

In the Footsteps of La Rebambaramba

English + Español

Tracing the journey of Amadeo Roldán’s Afro-Cuban ballet La Rebambaramba (1928) I arrived in Paris. Yes, in Paris, France… both the author of the original libretto, the Cuban writer and musicologist Alejo Carpentier, and the—also Cuban— choreographer Ramiro Guerra…

La Candela Viva

The drum beat is the pulse of Palenque de San Basilio; it is central to birth, death, marriage and other celebrations. In this Colombian town, drumming is about communion and…

A View of Afro-Diasporic History from Colombia

The Muntu Bantu, a memorial museum and cultural center in Quibdo, Chocó, on Colombia’s Pacific coast region, seeks to work “for the study, promotion and diffusion of the Afro…