Along Yvyrupa’s Paths

Beyond Borders

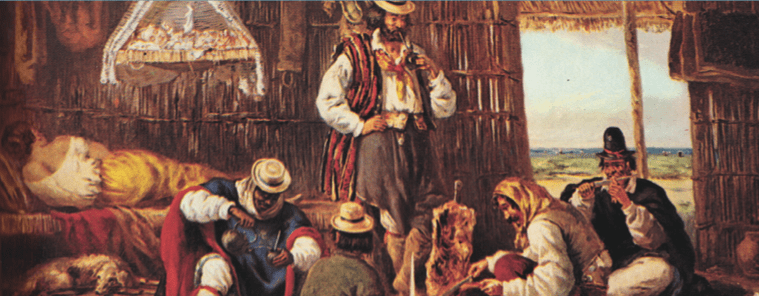

Painting by Brazilian artist Juan Leon Palliere (1865) of gauchos roasting food and drinking mate. From: Bonifacio Carril, El gaucho a través de la iconografía (Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1978).

My little sisters, my parents, it is true that all things here in the world are really difficult for us. Our word, every time it comes out of our mouths, it is Nhanderu eté (our true father) that releases it. Let him see that we talk, that we are happy. (…) From distant places, through the real walk, that is how you arrived to our village. We, as human beings in this land, we face many obstacles in order to keep in touch with other villages. However, through this walk that happened under the guidance of Nhanderu, because only he can open up our ways, it was possible for us to meet here on this land”

(Shaman from Fortin Mborore, 1997).

I started living with the Guarani in September 1978, after the inhabitants of a small village on the outskirts of São Paulo built a modest wooden room as their own school and had asked the government for an instructor to teach them to read and write in Portuguese.

I lived with the chief’s (cacique) family. Often, at dusk, he sat in front of his house and welcomed recently arrived visitors. Conversation quickly followed and, depending on the subject, there was mate or tobacco. Throughout the two years dedicated to teaching this community, although I did not master the Guarani language, I learned to recognize those people that came from distant villages, bringing seeds, medicinal plants and other goods offered as gifts to relatives in addition to news. Sometimes they spent long periods of time in the village to sell handicrafts in town and participate in rituals. Gradually, I was able to understand the close ties between the villages located on the Brazilian southeast coast and the countryside of Paraná state, with which this community had close ties, and learned who their shamans and caciques were.

In the following years, I started working towards the recognition of indigenous territorial rights at the Center for Indigenist Work (Centro de Trabalho Indigenista, CTI), and I had the opportunity to visit Guarani villages in other regions of South America. I came to understand that the spatial configuration of their villages relates to the social thread in a continuous composition. Old and new relationships interact, integrating the past and projecting the future of the village’s territorial basis. The comings and goings of generations result in constant communication, allowing for the renewal of experiences and updating memories, while continuing to exchange knowledge, rituals, and growing and breeding practices.

Throughout the centuries, the Guarani territory has been formed by an intense and extensive network of relationships crisscrossing national borders, political boundaries and administrative divisions. The Guarani population at the time Europeans arrived is estimated to have been two million; it is currently 250, 000 (including Bolivia).

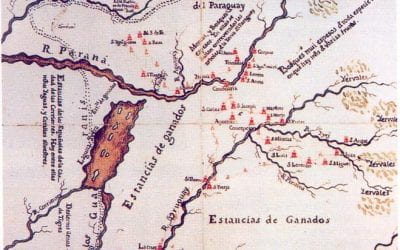

During the 16th and the 17th centuries, chroniclers identified as part of the “Guarani nation” groups sharing the same language found from the Atlantic coast to the Andean slopes, inland: communities were named after rivers, streams, or after characteristics based on physiography and/or political leadership models. Linguistic, social and cultural variations found among these groups were sometimes indicated, in time and space, through the use of various ethnonyms.

Despite current Brazilian classifications—Mbya, Nhandéva, Kaiowa—and their correlates from different countries, new arrangements among subgroups were promoted by the advent of colonization, the operation of Jesuit missions and indigenist politics, but, above all, by the Guarani social dynamic itself.

Currently occupied Guarani lands are discontinuous and small in size, interspersed with farms, roads and cities with little or no native forest. For this very reason, these remaining forests are crucial to maintain the balance of the Guarani way of living. Given the shortage of fertile land in the slopes, in order to practice their ancient cultivation techniques, the families living in the Atlantic coast need seeds and other traditional produce grown by those living on the hinterland plains. Likewise, families living in regions deforested by agribusiness benefit from native species found in wooded villages.

The Guarani conceive their traditional territory as the base that sustains their villages, which, in turn, support the world. The process of expropriation of their traditional territory takes on a multiplicity of meanings about the nature of borders, as experienced by Guarani families dispersed all over their extent territory.

Guarani families living in Guaíra on the border between Brazil and Paraguay are a case in point of such a loss: after having their ancient lands plundered by agricultural and animal husbandry exploitation or mostly destroyed by the flooding caused by Itaipú’s construction, they live, at present under critical conditions, without even having recognized citizenship. Close to the Atlantic Ocean, and very distant from the border area, conflicts caused by land expropriation and struggles for the recognition of historical Guarani rights also proliferated. The most frequent strategy employed in depriving the Guarani from their lands is to label them as foreigners, no matter which side of the national borders they live on.

Even if constantly living under restricted situations, the Guarani people as a collective precept claim to have no borders. Their domain over a vast territory has been asserted by the fact that their social and reciprocal relations are not exclusively bound to villages located in the same region. They take place within the framework of the “world,” in which linkages between distant and close villages define this people’s spatiality.

The Guarani still claim the amplitude of their territory, even if they do not hold exclusive rights over it. This territorial space where their history and experiences have been consolidated is called Yvyrupa (yvy=land; rupa=support), which, in a simplified translation, means terrestrial platform, where the world comes into being. According to the Guarani, the act of occupying Yvyvay (imperfect land) follows the mythical precept related to the origin of their humanity, when ancestors from distant times were divided into families over the terrestrial surface (yvyrupa) in order to populate and reproduce Nhanderu tenonde’s (our first father) creation.

In the course of my work, I was able to observe some aspects of Guarani’s spatial mobility. I knew that contact among people, even when they are set apart by national borders, happens in their own ways, including by crossing rivers, using different means of transport or walking. The CTI stimulated many exchanges of seed and plants, but I hold a special memory of the first trip I made. My aim was to observe how the Guarani living on the Brazilian coast, at the tip of the world (yvy apy), and their counterparts in Argentina and Paraguay would talk about the world. I assumed I would hear theoretical statements about their multifaceted territory’s current conditions, declarations that would extrapolate the political discourse produced by the young leadership.

On the morning of January 1997, a group formed by spiritual leaders and elders from seven villages headed west with their luggage filled with memories of different times and places. The journey began in Barragem village, São Paulo, which was coincidentally, the first village I had ever visited. Five villages were visited in Argentina and five more in Paraguay. The first one was Fortin Mborore, where we arrived late at night, after the inevitable problems on the borders. The farewell took place 18 days later, at the ruins of Trinidad.

In each village, the inhabitants, standing in line and following protocol, would greet us: porã eté aguyjevete! The visitors were welcomed with the sound of flutes, maracas and rabecas, or celebrations in the Opy (the ritual house). After this, hosts and visitors’ speeches alternated. Speeches about the journey’s significance and critical comments on the gravity of the landholding situation stood out.

These speeches deserve to be analyzed carefully in their entirety, but that would go beyond the scope of this article. I transcribe only part of the texts that depict common principles, recognized in rhetoric as the origin of ceremonial words re-elaborated according to current local circumstances and according to the idea of a land with no state borders. In these greetings, mentions to the relevance of the walk (guata porã) oriented by deities and following mythical precepts stand out. During highly emotional moments, leaders would refer to the task of achieving yvy marãey (the eternal land, where all deities live).

• I don’t know how to reach the word of the old ones to greet you. Admittedly human, I can not reach a word that comes from Nhanderu. We are already grownups, for this reason we already know what is good and what is bad. We are already old, for this reason we know how to thank him, the one who created humanity, we, the Nhandéva, men and women (…). For this reason, you also came to this land and you will see beautiful things that our ancient grandfathers have left to us, (…) it was him who gave courage to you so that we could communicate with each other, play and speak. And may this strength pass to our children, granddaughters and grandsons. I don’t have many words, but your presence makes me happy.

• I am speaking, me, for being human, I also have difficulties to reach wisdom. Despite this, no matter where we are, we are all equal, we speak the same language and we know how to see. (…)

• This is the reason why we are making efforts to have only one thought, everywhere, always with the same strength. We all want to have health, the same joy, the strength you have, we want to have it. Because we are relatives, brothers, the blood that flows in us is the same.

• I came to see my relatives. I was at Iguaçu village when they arrived and I came along with them. I saw many beautiful things (…) we remembered our relatives and together we worked to follow the same words in Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil (…). Because, we caciques will assemble and, as for today, we will have no borders. We, the Guarani, will go to any village.

• No matter where we walk or where we go, it were Nhanderu Kuéry (our divine fathers) that have put it on this world, the place where we step. (…) and this has happened because of Nhanderu, only he can free the way.

• I also want to say a few words. It is true, many things are difficult. Not all roads are free for us. There are many evils that can hit us. (…) But with the help of Nhanderu, you made this journey and this is good for us and for you too. So, it is Tupã’s son that protects us. (…) it is Nhanderu’s will that this event goes forward, that it happens again.

• Everyone that came will not easily be forgotten. I will keep to the rest of my life the place where our grandparents stepped, planted and tried cross to Nhandery retã (Nhanderu’s place, yvy marãey, the land of eternity). We believe in Nhanderu so that he further enlightens our thoughts, so that we follow the same path as our old grandparents.

• We saw the place where the old ones managed to cross to yvy marãey. They are the ones who were left and I saw the elders’ efforts to cross the world. (…) the grandparents that did not succeed, walked down by the sea so that they could cross it from there (…) for this reason, we have to look at the ocean (…) everyone that lives today has the same destiny and those who strive will succeed.

• I am very happy because my relatives came here to our village. Today, you are already going back to your villages. You, that are my grandmothers and grandparents are already grown (…) When you arrive to your village we want you to remember us and to tell to your grandchildren about us. I did not believe when you arrived. But what is important is that I saw my grandmother, now, your hair is already white, because your mother and father gave much advice to you and you followed it. (…) And you have already seen me as I am. So, now that you are leaving, I am left with this sadness in my heart. But what can I do? (…) I told myself: I no longer have my grandmother, the grandmother I had is already dead, but I saw that I have another one, and that you are already a grown-up. So, now you know, my grandmother, that I come from a village called Pastoreo. (…) I am a leader and I am really happy. You will go back to your village and you are taking a part of me with you.

In engaging with Guarani paths, it becomes noticeable that while Mercosur establishes commercial rules, it does not take into account intensive and widespread flows of interchange that have been happening for centuries among hundreds of villages that, together, make up the same territory. Nonetheless, the bonds and flows among the Guarani people have not been interrupted. Despite all problems related to the recognition of their land rights and citizenship, and other bureaucratic formalities, the Guarani people continue on their timeless paths.

Recorriendo Yvyvrupa

Por Maria Inês Ladeira

Mis hermanas, parientes, es cierto que todas las cosas que se encuentran en este mundo son difíciles para nosotros. Nuestra palabra, cuando emerge de nuestra boca, surge como Nhanderu eté (nuestro verdadero padre). Permitan que él vea que conversamos, que estamos felices. (…) Desde lugares distantes, a través de la caminata verdadera, fue como llegasteis a nuestra aldea. Nosotros, en nuestra condición humana, enfrentamos en esta tierra muchos obstáculos para mantener el contacto entre nuestras aldeas. Sin embargo, con esta caminata, llevada a cabo mediante la orientación de Nhanderu, porque solo él puede abrir nuestros caminos, fue posible encontrarnos aquí en la tierra!

(Chamán de Fortin Mborore, 1997).

Empecé a convivir con los Guaraní en setiembre de 1978 cuando los habitantes de una pequeña aldea, situada en la periferia de São Paulo, construyeron un cuarto de madera para hacer su propia escuela y solicitaron al gobierno una profesora para alfabetizarles en portugués.

Yo me hospedaba en la familia del dirigente político. Muchas veces, al caer la tarde, me sentaba delante de su casa y recibía visitantes recién llegados que hacia allí se dirigían. Una breve conversación y, dependiendo del asunto, un cimarrón o unos cachimbos. En los dos años que me dediqué a enseñar en esta comunidad, a pesar de no dominar la lengua guaraní, aprendí a distinguir a las personas que venían de aldeas lejanas, trayendo, además de noticias, semillas, plantas medicinales y otros bienes para regalar a sus parientes. A veces, se quedaban largas temporadas para vender artesanía en la ciudad y participar de rituales. Poco a poco, conseguí imaginar como eran las aldeas situadas en el litoral sudeste de Brasil y en el interior del Paraná con las cuales esta comunidad mantenía relaciones más próximas, y quién eran sus chamanes y líderes.

Durante los años siguientes me dediqué a trabajar por el reconocimiento de los derechos territoriales indígenas junto al Centro de Trabajo Indigenista – CTI, y tuve la oportunidad de conocer aldeas guaraní en otras regiones de América del sur. Comprendí entonces que la disposición espacial de sus aldeas está asociada a un entretejido social en continua composición; relaciones antiguas y nuevas interactúan, integrando el pasado y proyectando el futuro de sus bases territoriales. Los movimientos y las articulaciones impulsadas por sus generaciones se encuentran en comunicación constante, renovación de experiencias, actualización de recuerdos, y en un continuo intercambio de saberes, de prácticas rituales, de cultivos y de especies naturales.

El territorio Guaraní está formado por una intensa y extensa red de relaciones, a la cual se superpusieron, secularmente, fronteras nacionales y centenas de divisiones político-administrativas. Durante la expansión de la colonización la población guaraní fue drásticamente reducida: estimada en aproximadamente 2 millones de individuos cuando llegaron los europeos, hoy son contabilizados cerca de 180 mil.

En los siglos XVI y XVII, los cronistas identificaban como pertenecientes a la “nación guaraní” a los grupos de mismo lenguaje que se encontraban desde la costa atlántica hasta las laderas andinas, en el interior del continente: comunidades designadas por el nombre de ríos, cursos de agua, características fisiográficas y/o respectivos liderazgos políticos. Variaciones lingüísticas, sociales y culturales de esta población han sido puestas de manifiesto en algunas ocasiones en el tiempo y espacio, con el uso de diversos etnónimos.

Pese a las clasificaciones vigentes – Mbya, Nhandéva y Kaiowa en Brasil y a los correlatos en los países vecinos -, tanto la colonización, como las misiones jesuíticas, las políticas indigenistas y, sobretodo, las propias dinámicas guaraní promovieron nuevos organizaciones entre subgrupos.

Las tierras ocupadas por los Guaraní son actualmente diminutas, discontinuas, entrecortadas por haciendas, carreteras, ciudades, disponiendo de poca o ninguna área de floresta. Por eso mismo, en conjunto, son fundamentales en su interacción para mantener en equilibrio el modo Guaraní de vivir. Debido a la escasez de tierras fértiles en las áreas de pendientes para poder practicar sus técnicas milenarias de agricultura, las familias que viven en aldeas en el litoral atlántico necesitan semillas y otros cultivos tradicionales de tenencia que se encuentran en las aldeas en las llanuras del interior. De la misma forma, las que viven en regiones deforestadas por el agro-negocio, se benefician de la existencia de especies nativas encontradas en las aldeas forestales.

Los Guaraní conciben su territorio nacional como la base que sustenta a sus aldeas, que a su vez, dan soporte al mundo. Por tanto, sería poco decir que las secuelas de la expropiación colonial pudiesen recubrir la multiplicidad de implicaciones que representan incontables fronteras, concebidas en sus más diversos sentidos y vividas por las familias Guaraní dispersas en la amplitud de su territorio.

Las familias Guaraní que viven en Guaíra, en la frontera de Brasil con Paraguay, son un ejemplo candente: Después de haber sido expoliadas de sus tierras ancestrales debido a la exploración agropecuaria y a la inundación de gran parte de ellas tras la construcción de la hidroeléctrica Itaipú viven hoy en condiciones críticas, sin tener siquiera la ciudadanía reconocida. A orillas del Océano Atlántico, distante de las áreas fronterizas, también proliferan los conflictos que resultan de la expropiación territorial y de los enfrentamientos por el reconocimiento de los derechos históricos Guaraní. La estrategia utilizada con mayor frecuencia para destituir a los Guaraní de sus tierras es tacharlos de extranjeros, en cualquier parte de las fronteras nacionales.

A pesar de vivir constantemente situaciones límite, los Guaraní toman creen como precepto colectivo no poseer fronteras. El dominio de un amplio territorio se afirma en el hecho que sus relaciones sociales y de reciprocidad no se limitan exclusivamente en aldeas situadas en una misma región. Estas ocurren en el ámbito del “mundo”, donde las articulaciones entre aldeas próximas y distantes definen la espacialidad de este pueblo.

Los Guaraní conservan la amplitud de su territorio a pesar de no poseer exclusividad sobre este. A ese espacio territorial, donde consolidaron su historia y experiencia, le llaman Yvyrupa (yvy-tierra; tupa-soporte) que traducido de forma simplificada significa plataforma terrestre, donde el mundo sucede. Para los Guaraní, la ocupación de yvyvai (tierra imperfecta) sigue el reglamento mítico relacionado al origen de su humanidad, cuando los antepasados de un tiempo lejano se distribuyeron en familias sobre la superficie terrestre (yvyrupa), para poblar y reproducir las creaciones de Nhanderu tenonde (nuestro primer padre).

Debido a mi trabajo, pude reparar en las características de movilidad espacial guaraní. Sabía que los contactos entre personas, aunque estuviesen separadas por fronteras nacionales, se producen por vías propias, incluyendo travesías de ríos, medios de transporte y caminatas. Varios intercambios de semillas y especies vegetales fueron estimulados por el CTI, aunque guardo un buen recuerdo del primer viaje del que participé. Quería observar cómo los Guaraní que viven en el litoral de Brasil, en la punta del mundo (yvyapy) y sus iguales en Argentina y Paraguay, conversarían sobre el mundo actual. Presuponía que oiría pronunciamientos teóricos sobre las condiciones actualidades de su territorio multifacético que extrapolasen el discurso político, producido por los jóvenes líderes.

De ese modo, una mañana de enero de 1997 un grupo formado por dirigentes espirituales y ancianos provenientes de siete aldeas, con su equipaje repleto de recuerdos de lugares y tiempos, se dirigió hacia el oeste. El viaje se inició en la aldea de Barragem, en São Paulo, casualmente la primera aldea que conocí.

Fueron visitadas cinco aldeas en Argentina y cinco en Paraguay. La primera, a la que llegamos a altas horas de la noche después de inevitables dificultades en la frontera, fue Fortin Mborore. La partida, 18 días después, fue desde las ruinas de Trinidad.

En cada aldea, los visitantes, en fila, siguiendo el protocolo, se saludaban: porã eté aguyjevete! Al sonido de flautas, maracas y rabecas, o en celebraciones en las Opy (casa de rituales), dieron abrigo a los visitantes. Después de aquellos momentos, las palabras de los anfitriones y visitantes se alternaban. Destacaban discursos sobre el significado del viaje y críticas relacionadas a la gravedad de la situación agraria.

En su totalidad, esos discursos merecerían un análisis más cuidadoso, lo que ultrapasa los límites de este artículo. Transcribo únicamente algunos fragmentos que expresan principios comunes reconocidos en la retórica, en el origen de las palabras ceremoniales reelaboradas conforme las circunstancias locales y en la percepción de una tierra sin fronteras estatales.

En las salutaciones, se destacaron menciones a la relevancia del caminar (-guata porã) orientado por las divinidades, siguiendo órdenes míticos. En momentos de mucha emoción, los dirigentes se refirieron a la intención de alcanzar yvymarãey (la tierra de la eternidad, donde viven las divinidades).

- No sé llegar a palabras de los antiguos para recibiros. Yo que soy humano no consigo alcanzar una palabra que venga de Nhanderu. Ya somos adultos y por eso sabemos lo que es bueno y lo que es malo. Ya somo viejos, por eso sabemos agradecerle a él que generó la humanidad, a nosotros los Nhandéva, a hombres y mujeres (…). Por eso vosotros también vinisteis a esta tierra y veréis las cosas preciosas que nuestros abuelos antiguos dejaron. (…) fue él que os dio el coraje para que nos comuniquemos, juguemos y hablemos. Y que esa fuerza pase a nuestros hijos, nietas y nietos. Yo no tengo muchas palabras que decir, pero vuestra presencia me hace muy feliz.

- Estoy hablando, yo, que soy humano, también tengo dificultad en alcanzar la sabiduría. Aún así, allí donde estuviésemos, somos todos iguales, hablamos la misma lengua y sabemos ver. (…)

- Es por eso que estamos haciendo un esfuerzo para tener un solo pensamiento, en todo el mundo, siempre con la misma fuerza. Todos nosotros queremos tener salud, la misma alegría, la fuerza que vosotros tenéis nosotros queremos tenerla. Porque nosotros somos familia, hermanos, la sangre que corre en nosotros es la misma.

- Yo vine para ver a mis familiares. Estaba en la aldea de Iguazú cuando llegaron y vine para acompañarles. Y vi muchas cosas bonitas (…) nos acordamos de nuestros parientes y juntos trabajamos para seguir las mismas palabras en Paraguay, Argentina y Brasil. (…) Porque nosotros, los líderes, vamos a reunirnos y, a partir de hoy, no tendremos más fronteras. Nosotros, los Guaraní, iremos a cualquier aldea.

- Por donde nosotros andamos, por donde nosotros pasamos, pasaron Nhanderu Kuéry (nuestros padres divinos) que pusieron esa tierra, donde nosotros pisamos. (…) y eso ocurrió por Nhanderu, sólo él puede abrir el camino.

- Yo también quiero decir algunas palabras. Es cierto, muchas cosas están difíciles. No es cualquier camino que se encuentra libre para nosotros. Hay muchos males que pueden alcanzarnos (…). Pero con la ayuda de Nhanderu, vosotros hicisteis este viaje y eso es bueno para nosotros y para vosotros también. Por eso, es el hijo de Tupã que nos protege. (…) es por la voluntad de Nhanderu que este acontecimiento sigue adelante, y que ocurra de nuevo.

- Todos los que han venido no van a olvidarlo tan fácilmente. Voy a guardarlo en mi memoria para el resto de mi vida, donde nuestros abuelos pisaron, plantaron y buscaron pasar hacia Nhanderu retã (el lugar de Nhanderu, yvymarãey, la tierra de la eternidad). Nosotros creemos en Nhanderu para que ilumine más nuestros pensamientos, para que sigamos el mismo camino de nuestros abuelos antiguos.

- Vimos el lugar donde los antiguos consiguieron atravesar hacia Yvymarãey. Ellos son los que quedaron y vi el trabajo de los antiguos para atravesar el mundo. (…) los abuelos que no lo consiguieron, anduvieron hasta la orilla del mar para desde ahí cruzar. (…) por eso, nosotros tenemos que mirar al océano. (…) todos los que viven hoy tienen el mismo destino y aquellos que se esfuercen lo van a conseguir.

- Estoy muy contento que mis parientes hayan venido hasta aquí a nuestra aldea. Y en el día de hoy vosotros ya vais a volver a vuestras aldeas. Vosotros que sois mis abuelos y abuelas ya habéis crecido. (…) Cuando llegues a tu aldea nosotros queremos que te acuerdes de nosotros y le cuentes a tus nietos.

- Yo no creí que llegases. Pero lo importante es que vi a mi abuela y, de esa forma, tú ya tienes los cabellos blancos porque tu madre y padre te dieron muchos consejos y tú los seguiste. (…) y que su fe continúe bien fuerte para todos, para tus familiares, tus nietos y nietas. (…) Y tú ya me has visto como soy. Así que en el día que os marcháis, se queda en mí esa tristeza dentro de mi corazón. Pero que le puedo hacer? (…) Yo dije para mi mismo: ya no tengo más a mi abuela, la abuela que tenía ya falleció, pero vi que tenía otra que eres tú que ya está crecida. Entonces usted ya sabe, mi abuela, que soy de una aldea llamada Pastoreo. (…) soy un líder y estoy muy feliz. Tú vas a volver a tu aldea y estás llevando ese pedazo de mí.

Al recorrer los caminos guaraní se puede constatar que el Mercosul, disponiendo de normas estrictamente comerciales, desconsidera el intenso y amplio flujo de intercambios que ocurren desde tiempos inmemoriales entre centenas de aldeas que comprenden un mismo territorio. Aún así, a pesar de las discrepancias relativas a los derechos territoriales, a la ciudadanía y a las formalidades burocráticas, los vínculos y flujos entre este pueblo, no han sido interrumpidos.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Maria Inês Ladeira is a member of the Center for Indigenist Work (Centro de Trabalho Indigenista, CTI) Coordinating Office. She holds a Ph.D. in Human Geography from the University of São Paulo and a Master’s Degree in Social Anthropology from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo.

Maria Inês Ladeira es Doctora en Geografía Humana por la Universidad de São Paulo, máster en Antropología por la Pontífice Universidad Católica de São Paulo. Miembro de la Coordinación General del Centro de Trabajo Indigenista.

Related Articles

Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of New Architecture

Growing up in the midst of the Irvine Company’s unimaginative southern California, without exposure to anything other than strip malls and suburban…

Transformed Worlds

In 1610, a small group of Jesuits began what would become known as one of the largest indigenous evangelism experiences in colonial America. The effort began…

The Many Meanings of Yerba Mate

I first encountered yerba mate as a Peace Corps volunteer in rural Paraguay. Everywhere I went, and at all times of the day, I saw small groups of people…