Amazônia Redux

A Reevaluation of Urgent Needs

Photos by Renato Soares / Imagens do Brasil

A meeting with a group of indigenous leaders, during my recent trip to the Amazon, still resonates with me to this day. I met with them in Atalaia do Norte—the riverside entrance to the Javari reserve, a region in the Javari river basin. They wanted to share concerns about the threats to their people, environment and culture. Among the discussions about the ways to defend their people, the words of Tumi Manque Matís from Javari’s Matsés tribe stood out: “Our land (the Javari reserve) is important for us. We are different ethnicities living in a communal system. Although we belong to a number of different groups —Matses, Kulina, Mayoruna, Korubo, Kanamari and others – we are in the Javari reserve we are one. We want to keep it that way. The hope of our leadership is to preserve a future for our children.”

Tumi Manque Matís makes an urgent call to think about Amazonian territory, socio-diversity and biodiversity with a new perspective on relationships, because the divide between nature and culture no longer makes sense. Nature is culture. Culture is nature. There are, in reality, many Amazons that reveal a variety of tastes, colors, ideologies and occupational projects. Unfortunately, today none of these form part of a government project, a project which should respect the self-determination of indigenous people and communities, and whose interaction with the academic community could generate vital knowledge for the new, more urgent conditions of life on this planet. The Amazon offers a model that generates peace and alliances between people; between outsiders and those that live in the forest. A model that teaches stewardship of the forest to our citizens, whose precarious lives are currently based on the consumption of objects, which have built-in, planned obsolescence and whose manufacture and disposal create continual environmental contamination.

Throughout historical memory, the Amazon region has undergone various reimaginings by external subjects. This began with its very name, a tribute to the Greek myth of the Amazons. With its previous history utterly ignored, since this epistemological break (its rebaptism as an offspring of Greek myth in the 16th century) the region has experienced more than 500 years of hardship imposed by predatory systems of exploitation. Whether it was the exploitation of animal life or vegetable life, minerals or waters, such practices have often defined the tragic destiny of its communities. And, from this year on, it will be redefined once again, under the new Brazilian administration in command of a conservative neoliberal agenda. Another round of disruptive policies is being implemented, contrary to the good living (Bem Viver) explained by Alberto Acosta. For Acosta, good living does not stem from an academic-political proposal, but rather embodies the opportunity to learn from the diverse realities, experiences, practices and values present in different habitats, even today, in the midst of capitalist civilization. We are witnesses again as another group of subjects from outside the Amazonian territory attempts to determine who should inhabit the land and, tires to enforce their experiment.

Spring/Summer 2020, Volume XIX, Number 3

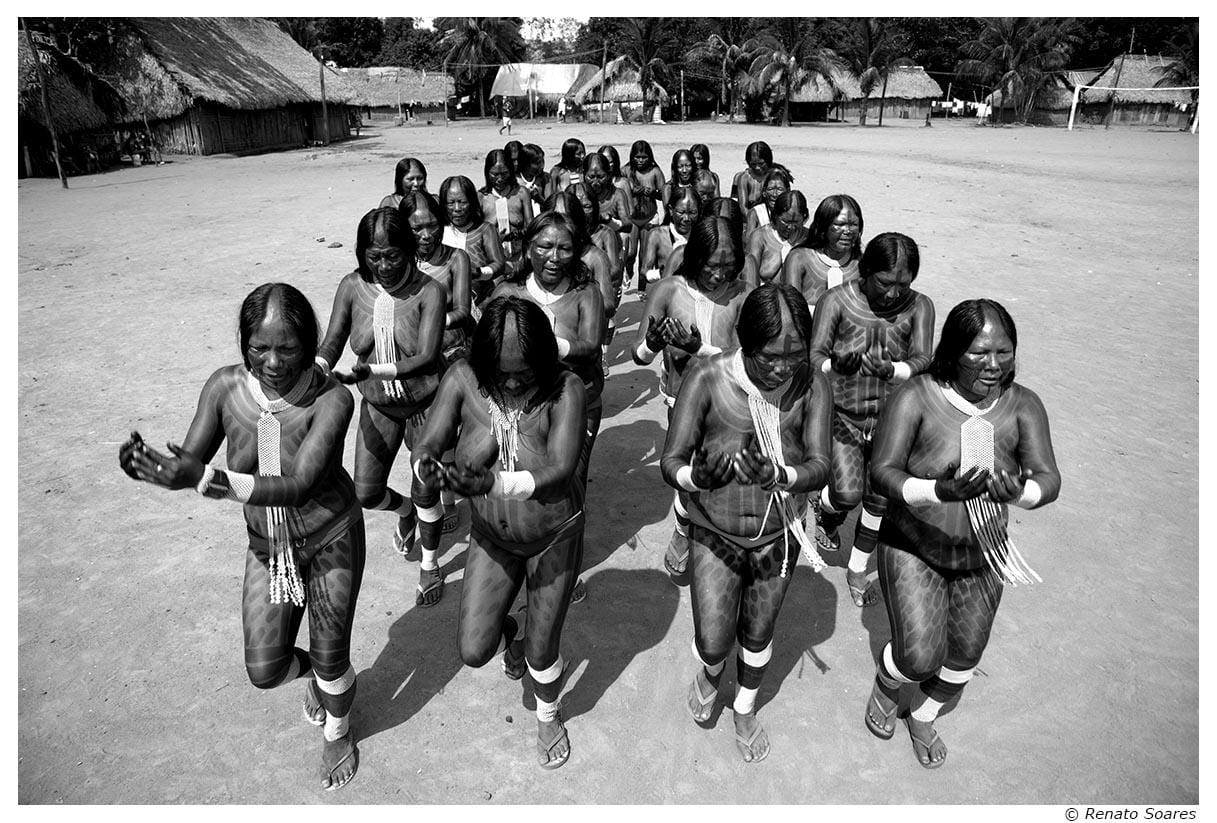

- Assunto: A festa das mulheres – Yamarikumã Local: Aldeia Kamayurá – Distrito de Gaucha do Norte Data: Agosto de 2012 Autor: Renato Soares

The most refined western science shared in magazines, books, numerous lessons, lectures and audiovisual demonstrations, proves that the best work and the best destiny for the Amazon and its peoples, both for the climatic destiny and the biodiversity of the planet, is to maintain and reproduce the complex relationships with the forest practiced by the people traditionally living there—the Indians, Quilombolas (Afro-Brazilian communities, formed by the descendants of slaves, who embody a traditional set of relationships with the natural resources and their territories), riparian (tradicional riverside communities), fishermen and extractivists of land and water. They are those who lived there long before the predators of the world market arrived, whether national or international. When we talk of western science, we can cite the U.S. Nobel Prize recipient Elinor Ostrom and the work she does to evaluate and endorse common use systems.

Let us think for a moment of an Amazon that does not appear in the media or in contemporary scientific imagination. The silence shrouding the vulnerability of traditional peoples to violence, the sociocultural and environmental dismantling of the Amazon and the economically and culturally predatory models pursued in large-scale projects, each stand as genuine problems that remain hidden. This silence is a key component of a ‘civilizing’ project which fails to engage Indians, Quilombolas, riparians, small farmers and forest workers, and cannot comprehend the Amazon’s cultural diversity and complex biomes. Recognizing this silence imposes on us all a new relationship with essential information , in which we must become researchers that critically seek-out, investigate and collectively share information. What is in play is the survival of us all, those living in the Amazon as well as the rest of humankind. When there is nowhere left for the Indian, there will be nowhere left for all of humanity. Sister Dorothy Stang, who was assassinated in February 2005, understood that “the death of the forest is our own death” – the phrase which was printed on the t-shirt she was wearing at the moment of her death.

Our difficulty stems from the fact that the Amazon has been inserted into a continuous process of renovated colonization, which did not end with Brazil’s independence. New times have led to new colonialisms: the forest continues as an outdoor laboratory for economic interests and ventures that fails to observe or question the impact of the invasion of lands and the submission of peoples to the various generations of conquerors. Indeed, even before the contemporary phase of Brazilian society, the State had no specific project for the Amazon, except that of surrendering it for sale to highest bidder (as currency to be exchanged for any form of experiment or intervention claimed to be productive). As if keeping the forest standing and reproducing it was not productive enough—something that Amazonian people have been doing for millennia—generating “flying rivers” that guarantee rainfall throughout South America.

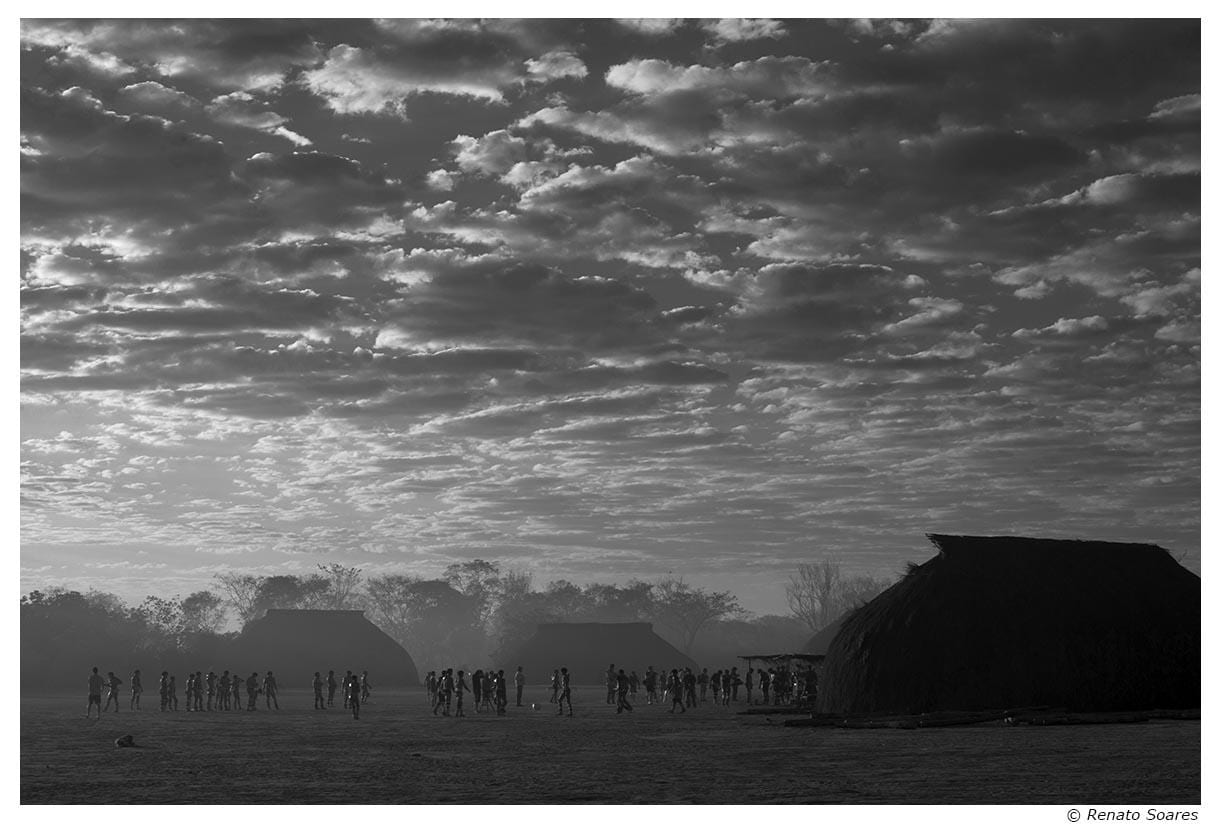

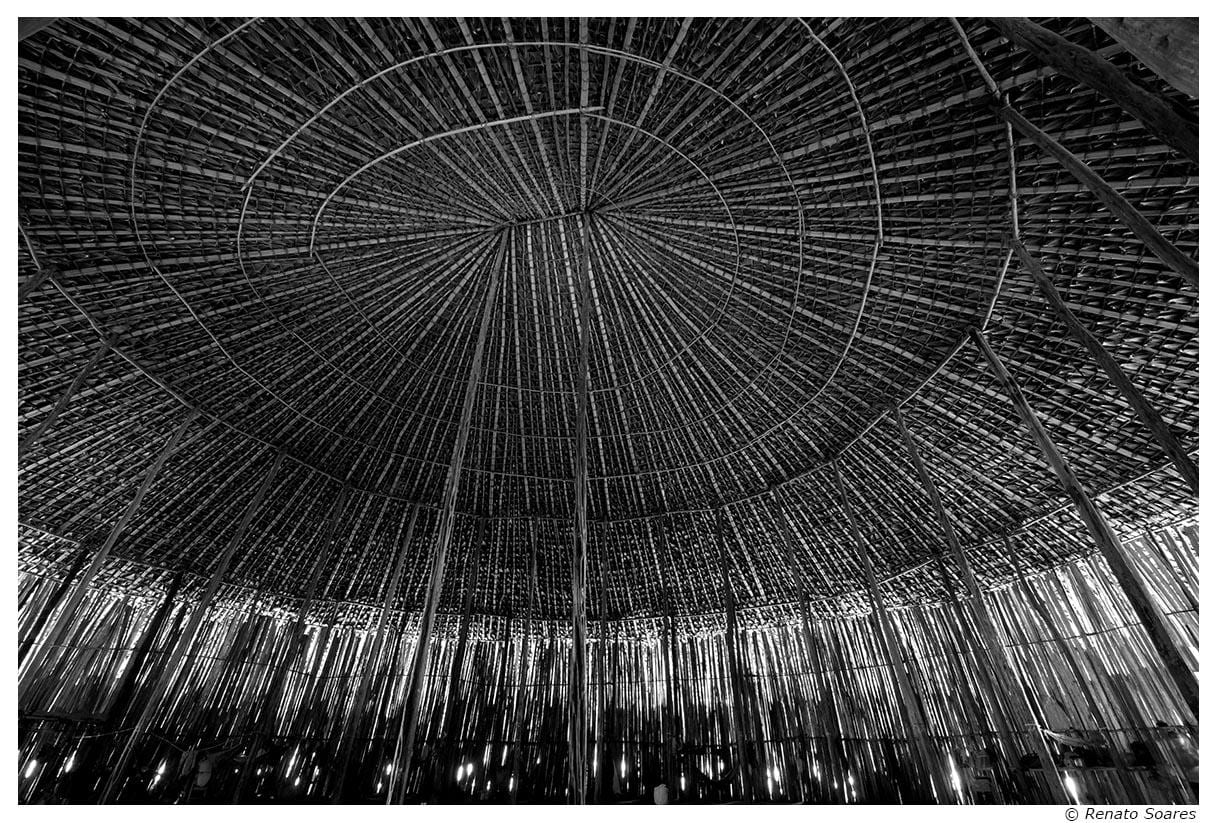

- Assunto: índios do Xingu – Kuikuro Local: Aldeia Afukuri no PIX – Distrito de Gaucha do Norte Data: Agosto de 2012 Autor: Renato Soares

The Brazilian government is still uncertain about how to cash in on the Amazon, as if the traditional people, together with the sciences, had not already found many solutions. However, these solutions do not conform to the greed of agribusiness, mining and extractive industries acting in the region. Currently, Amazonia is a territory of enclaves—in Mato Grosso, in the free trade zone of Manaus, Acre and Pará. These enclaves are oblivious to the dialogue between traditional peoples and the sciences, which nurtures the richest knowledge of the region. Among other groups, indigenous peoples are also producers of scientific knowledge and hold a critical understanding of how the Amazon region could be managed.

The Amazon occupies around 61% of Brazilian territory; 25 million people live there. There are around 300 ethnicities and 180 languages – these are all ways of experiencing, experimenting, feeling, and imagining the world—this world that so urgently needs new solutions so that all of humanity may finally live in a state of well-being. After all, civilized well-being never arrived spontaneously for anybody. The radical subjugation to the West configured by the “indigenous,” who have been silenced for as long as can be remembered, has continually paid the bill for this malaise in civilization. Sadly, indigenous reserves are treated as the new economic and extractive frontier by a new Brazilian government, that remains eager to allow their territories to be exploited by national and international corporations, with which it curries favor by restricting the already tenuous pro-Indian legislation.

In synthesis, the biggest problem of the Amazon is this slow, continuous violence of incommunicability between the government, powerful economic interests and the majority of its people. Communication should be meaningfully pursued and this can be achieved if it is based on scientific interest in the present and future of humankind. However, incommunicability subjugates most Amazonian inhabitants and subverts what could be truly, contemporary national policy in Brazil. It sabotages any autonomous project that seeks to preserve culture, biomes, memories and our history. Against this fabricated ignorance, we have science, traditional knowledge and memory.

The end of the Amazon would be the end of the heart of humanity, not in the biological sense of the heart; as common sense so often said, substituting the heart for the lungs; but the heart in the poetic sense. The heart in the sense that poetic and scientific imaginations are forces that should guide the genuine dialogue between public policy and the people of the forest.

The people of the Javari reserve are fighting not only for the forest but for the education of their people as a tool to their own survival. In my conversation with the faculty members at the Federal University of the Amazon in their campus in Benjamin Constant they informed me that 1,414 students were registered in 2019. Of these, 432 come from the ethnicities of the reserve: 115 Komanas, 34 Kambeba, 1 Kamanari, 40 Kaixana, 5 Marubo, 2 Mayruba, 272 Tikuna and 3 Woitoto. Their fields of interest are divided as follows: 46 business, 72 education, 69 anthropology, 82 languages, 88 biology and chemistry, 77 agroecology.

The indigenous people of the Javari have much more to teach us in addition to their new perspectives on relationships. Their effort to go to the nearby cities to get an education shows the desire to learn to equip their own communities. Should we not do the same: learn from indigenous knowledge and teach our peers their riches?

Marcos Colón leads the Portuguese program at the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics at Florida State University; he is also the writer, director and producer of Beyond Fordlândia: An Environmental Account of Henry Ford’s Adventure in the Amazon.

Related Articles

Amazon: Editor’s Letter

The Amazon is burning. The trees that have not been cut down are on fire. The crisis is now. When I began to work on this issue on the Amazon, that was pretty much my vision, and it was a real one. I was determined to make the magazine on the Amazon about…

How Democracies Die

How Democracies Die analyzes the main dangers that modern democracies face. As the authors warn, 21st-century democracies do not die in one fell swoop, in a violent way, by hands that do not always belong to the political system. On the contrary, modern democracies…

The Return of Collective Intelligence

My college Native American Culture professor, the Mescalero Apache scholar Inez Sánchez, told our class that we should regard the word “primitive” as synonymous with “complex.” I gained a better understanding of what Sánchez meant reading The Return of Collective…