Andean Traditions of Giving

In Andean tales, the fox is always the central figure, a hero who never wins, but who is also never defeated either. His comings and goings stretch from mythical times to colonial history, when he becomes the champion of the suffering Indian peons of the hacienda, along with Pedro Urdimales, a European fairy tale character who came to the Andes in the 16th century.

In the story, the fox calls himself Antonio and is transformed into a young gentleman who wins the heart of every young lady who crosses his path. This adventurous character with his winning ways gets nicknamed Tiwula, from the Spanish word tío or uncle. The gallant fox is always struggling and trying to become really human by marrying one (jaqi, human) and making himself a son-in-law (tullqa). He certainly manages to win women’s affection and seduce them. However, his attempt to marry a jaqi are in vain. At the last moment, the woman always dies or his real identity is discovered just before his wedding day.

The fox is always a stranger who comes from above, jaya in Amayra, jawa in Quechua. He is the Andean sex symbol, which represents masculinity, much appreciated by both men and women. In traditional fiestas and rituals, the sons-in-law are represented by this figure, making quinoa crackers with the figures of a fox. Nowadays, these crackers are more likely to be rolls made from wheat flour. The most ritual and mythological symbol is the lari.

Historically, those spirits who inhabit the very highest mountains in the Andean region are called lari lari and chuqilas, the last term associated with lightning. The lari lari, is the sacha or savage from the summits, barely earning a living raising native species such as llamas and alpacas and dedicating themselves to hunting vicunias (vicuñas) known as wanakus and waris with riwi, a type of dart. In addition to representing lightning, the chuqila brings the frost necessary to dehydrate potato (chuño).

In this essay, we will discuss two examples of storytelling and a ritual in which the fox plays a central part, in which he symbolizes the particular relations of reciprocity that the human community establishes with this representative of nature.

In the Andean region, glossaries that spell out the indigenous traditions of giving and reciprocity are quite well known. Like the Eskimos, who have many different words for snow, the Andean peoples have many different words for practices of reciprocity, words like ayni, mink’a, waki, sataqa, etc. that refer to the circulation of goods, energy, and services that make communitarian life successful in the lofty plateau known as the altiplano. This exchange of goods and services also has to do with a very particular concept of space, the transversality that crisscrosses between the flat Pacific coasts and the highlands, between the valleys nestled among the Andes and the plains of the Amazons. This transversal vision of space, expressed in storytelling and ritual, reflects ecology and the rich biological diversity through its symbolic animals, who interact reciprocally with the human community. The high mountains of eternal snow are represented by the condor, khunu t’uru (he who crushes the snow) in Aymara, while the high plateau is symbolized by the fox and the Amazons by the jukumari bear.

The Fox as Liberator

In a story published by Bolivia’s Human Development Ministry in collaboration with the Andean Oral History Workshop in 1996, it’s recounted how people were suffering a lot because the puma were eating all the llamas. No one knew what to do. One day, the elders happened upon Tiwula, who immediately offered to resolve the problem if he were paid in llamas. So the people and the fox collaborated in a successful plan to capture the puma. And although the fox was paid his share of llamas, he asked for them to be left behind for the community or ayllu to take care of. He said he would be back when he needed the llamas.

Since that time, when the fox takes one animal or another, people have to accept that it’s something that corresponds to him. They never mention the name qamaqi , which literally means “fox” in Aymara, but call him by the respectful name of “uncle,” tiwula.

This tale indicates how reciprocity between man and nature has fostered a concern for ecology, that sometimes might even seem against the common sense interests of the community.

The Cosmic Zorro Cósmico (Pachaqamaqi)

The Aymara’s spirit–pachaqamaq or cosmic fox–inhabits his body, entering and leaving through his ears. According to a version of this story published by the Workshop, the fox travels to the pacha or cosmos on the wings of a condor. Among his many aventures, he eats the fruits he likes the best and dedicates himself to seducing women. He doesn’t pay any attention to the condor’s pleas that he return to earth. It gets to be very late, so the condor returns to the earth by himself. The fox desperately looks for a way to get back to earth and comes up with the idea of a rope (phala de jichhu). On his way down to earth, he comes across some parrots, k’allas, who make fun of him. The fox taunts them back, and they cut his rope with their beaks. He hurtles down to earth, yelling to the spiders to help him by hastily spinning a web to break his fall. He dies and all the fruit he has eaten falls out of his belly. Since then, the people plant and eat all the varied and rich cosmic fruits that the fox brought down to earth. In reciprocity, people celebrate the fox at the end of the harvest and have made him part of their mythical geneological tree.

Chuqila

The Chuquila ritual during three days of fiesta, music, and theatre, takes place during the harvest season in the altiplano communities.

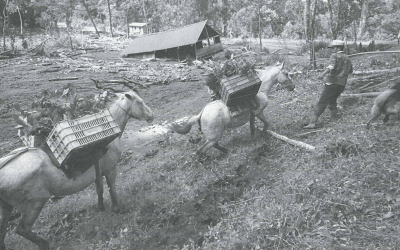

It recreates the arrival of a community of chuqilas to the pampa, to look for agricultural products to exchange for animal-derived products. The encounter is synthesized in the songs and culminates in a party in which the chuqilas play instruments and dance imitating vicuñas. The participation of the ayllu, the community from the plains, is in the dance, represented most often by women. These chuqilas are travellers, most often single men. Here it is very clear that the symbolism of the fox as a representative of masculinity and, in a more subtle sense, of lari or generosity. Chuqilas come down from the hills with their herd of llamas and their traditional costumes, still used today. They are greeted by the community of the flatlands through song and an exhibit of fresh fruit.

Just before the fiesta, as a midnight prelude to the ritual, there’s a foxhunt, kicked off with song and a virgins’ dance. The fiesta’s high point is the counterpoint in the song between the young chuqilas and the girls from the plains, which ends in matrimonial alliances between both groups as a sign of the ecological alliance between the high plateau of the altiplano and the arid tablelands. The choreography of the dance imitates the vicuñas, culminating in a ritual imitation of copulation with a virgin.

The dance troupe and the community participating in the ritual carry out the symbolic sacrifice of the vicuña, which is then roasted, and a blood toast–represented by quinoa bread and wine. This ritual symbolizes inter-ethnic alliances between the two groups. Today’s Aymaras hold this celebration in May or June.

Spring 2002, Volume I, Number 3

Maria Eugenia Choque Quispe is the director of the Andean Oral History Workshop. She teaches at the Universidad Pública de El Alto (UPEA) and the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés in La Paz, Bolivia.

Carlos Mamani Condoria, a member of the Andean Oral History Workshop, studied history at FLACSO and is a professor at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés.

Related Articles

Obras de Infraestructura Básica de Fácil Ejecución a través de la Autogestión

En el Ecuador rural y en las zonas citadinas marginales, la carencia de servicios básicos se ha convertido en un mal endémico no resuelto hasta …

Responsabilidad Social Empresarial: Algunos Hechos Que Cuentan

La Responsabilidad Social Corporativa (RSC) es una temática más bien nueva en Chile. Aún cuando se encuentran acciones filantrópicas desde tiempos de la colonia, la relación de la …

Algunos Casos en Chile

Un caso fue José Tomás Urmeneta, un empresario del siglo XIX quien, en un momento de auge del sector agroexportador chileno, en su testamento dejó asignados recursos para …