Art and Politics in Brazil

En Route to an Artistic Vocation

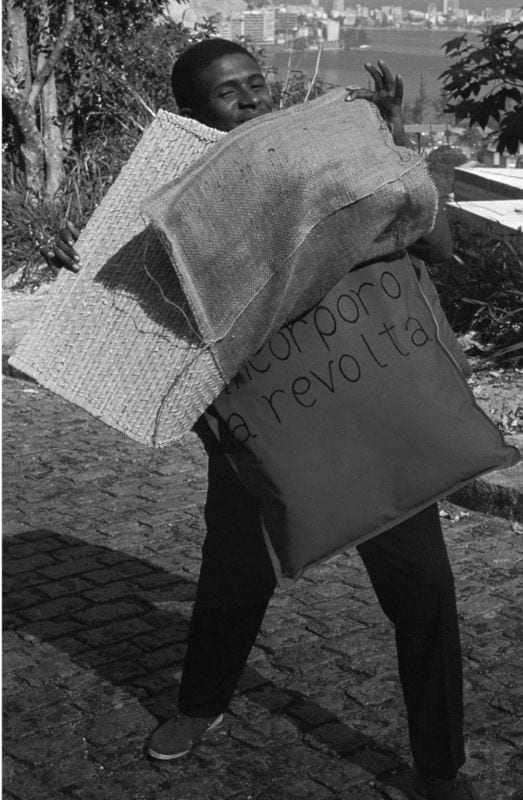

Nildo with Parangolé P15 Cape 11 (1967), Revolt (burlap, straw, leather, cotton fabric). Photo by Claudio Oiticica

Right at the eve of the military coup d’état that took place in 1964, there was an ongoing debate in Brazil about the relationship between art and society. Many artists and intellectuals were interested in forging a cultural production that was ethically and politically significant, but not necessarily nationalistic or ideological, as the orthodox left had prescribed. Artists associated with these new proposals were criticized both by the left and by the right. The left accused them of being elitists who lacked a social commitment to a grassroots cultural production oriented towards a revolutionary art. The right thought they were rebels spreading the seeds of communism throughout the country.

In the field of visual arts, the seminal Brazilian poet and critic Ferreira Gullar wrote Cultura posta em questão(Questioning Culture) in 1963, dismissing as elitist all art that valued aesthetic form over ideological content. He rejected what he called “bourgeois” art and called for a popular art ideologically engaged and socially committed to the masses. Gullar’s rupture with the experiments of the avant-garde came as a surprise. He had been one of the major spokesmen and advocates of the Neo-Concrete movement, with his “Neo-Concrete Manifesto” published in the Sunday Magazine of theJournal do Brasil on March 23, 1959. Some of the founding members of this movement were Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape, Willys de Castro, among others from Rio de Janeiro. The movement sought to liberate the visual arts from the rational and technological tone of the São Paulo Concrete movement, restoring an expressive and subjective approach to the work of art. In his manifesto, Gullar called for a move away from the mechanical and scientific concerns prevailing in geometric abstract art in Brazil, particularly by engaging the viewer as a participant in the work of art. Gullar, however, later became disillusioned with the apolitical tone that took over the latest developments in visual arts in Brazil.

If Gullar was the spokesman of the Neo-Concrete movement, Oiticica was its major exponent. The two of them engaged in an intense dialogue since the fifties. Like Gullar, Oiticica had participated in the Brazilian constructivist project that conceived of a modern universal language for the visual arts based on geometric abstraction, moving away from the regionalist tone that dominated the national production until then. Later, both theorists and artists criticized the excess of rationality of the Brazilian constructivist project, incorporating sensorial experiences in their Neo-Concrete phase. Although both Gullar and Oiticica shared similar concerns about the role of the artist in society, their subsequent investigations took different directions.

In his polemical Cultura posta em questão, Gullar put his finger on a crucial issue: “Can the vanguard in a developed country necessarily be the same one as in an under-developed country?” (Vanguarda e subdesenvolvimento: Ensaios sobre arte, p.185).

He argued that it would be naïve to pursue the same level of modernity as the European avant-gardes, since these refer to their own specific cultural realities. Vehemently attacking art that lacked a social or revolutionary function, Gullar began to promote the Centros Populares de Cultura (Popular Centers of Culture, the CPCs), a project connected to the National Student Union (UNE), which set out to foster popular Brazilian culture in slums, factories, and universities.

In 1964, while Gullar joined the Communist Party, Oiticica became a samba dancer in the Samba School Estação Primeira da Mangueira and spent much of his time at Mangueira Hill, one of the oldest shantytowns of Rio de Janeiro. Far from being a political militant, Oiticica was suspicious of any organized association. If anything, he was more of an anarchist like his grandfather, José Oiticica, than a follower of a systematic program prescribed by a political organization. An unaligned leftist, Oiticica was intrinsically engaged with the discussions about the social challenges posed to an artist in an underdeveloped country like Brazil.

He became interested in art drawn from the margins of society. He found his raw material where the vast majority of the illiterate and disenfranchised segment of the population lived: the favelas and the samba schools. Through the rituals and rhythms of Afro-Brazil Oiticica found his own avant-garde. At Mangueira Hill he found his collective body, as well as the cheap and abundant materials that would prevail in his work. He opened the doors to a contemporary artistic production embedded in what we can call “the aesthetics of the margins.”

In “Notes on the Parangolé,” written around the time of the exhibition Opinião 65 (Rio de Janeiro: Museu de Arte Moderna, 1965), Oiticica elaborates on the notion of the parangolés—capes to be worn by the audience as an unfolding development from his Neo-Concrete experience. The parangolés, in their forms and shapes, were an extension of his former experiments with geometric abstraction. The difference was that now his art was infused with the collective, social and individual bodies that had been excluded from his earlier constructivist work.

Oiticica brought members of the Mangueira School of Samba wearing his parangolés to do a performance at the museum’s salons. Samba dancers entered the museum wearing his capes and carrying his standards and tents, playing the drums, singing and dancing. The poet Wally Salomão, a close friend of Oiticica who liked to be called Wally Sailormoon, recalls their cold reception:

Dancers from Mangueira Samba School such as Mosquito, Miro, Tineca, and Rose…all in ecstasy enjoying the mess that they were promoting, people unexpected and without an invitation, without tie or suit, without handkerchief and documents, eyes open wide and in a state of pleasure invading the Museum. There was an evident subversion of values and behavior. They had been excluded from the ball, forbidden to enter. Then, Hélio unleashed his arsenal of bad words. (Wally Salomão, Hélio Oiticica: Qual eh o parangolé? Rio de Janeiro, Relume Dumará,1996, p. 51.) Author’s translation.

After the dancers were expelled, Oiticica took the crowd to the Museum garden. He started screaming that black people had been forbidden to enter the Museum, and that this was racism. Ironically, at Mangueira Hill, Oiticica was known by the nickname Russo (Russian) since he was the whitest among all of them.

The word parangolé is slang for a mundane question: “Qual eh o parangolé?” (What’s up bro?) Some of the parangolés had inscriptions such as Estou Possuído (I am Possessed) (P 17, Cape 13, 1966), in a double reference to being possessed by one of the deities from the Afro-Brazilian cult candomblé, or by the Dionysian experience of drugs and alcohol. On anotherparangolé (P 15 Cape 11, 1967), worn by Nildo da Mangueira, the inscription read: Incorporo a Revolta (I Incorporate Revolt), which could be revolt against the lack of social mobility or against the authoritarian rule imposed by the military dictatorship. It implied a state of aggression as well as a wish for transgression.

With his parangolés, Oiticica fluidly danced from the labyrinths of the slums of Rio to the city’s asphalt, navigating between high and low, shifting from the closed salons of the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro and its elite to the social reality of the shantytowns, from the experiments of the international avant-garde to Brazilian popular culture. He called them arte ambiental, a common term in Brazil in the late 60s and early 70s that was used broadly to describe any work of art challenging traditional media such as painting and sculpture. It could refer to an installation, or in the specific case of Oiticica, to his works incorporating the participation of the spectator. Far from promoting a revolutionary popular art to the “uncultured” people of the favelas, Oiticica incorporated their culture into his art.

Two years later, with his essay “Esquema Geral da Nova Objetividade” (General Scheme of the New Objectivity) written on the occasion of the exhibition Nova Objetividade Brasileira (New Brazilian Objectivity); Oiticica formulated the tenets for an avant-garde art in Brazil that would combine radical artistic innovations with an engagement with political, social and ethical issues. He believed that art was directly related to social change and advocated a collective art that could promote this change. He proposed that artistic practice be open to the participation of the spectator and committed to an audience beyond the elites.

For Oiticica it was not a question of choosing between an art with popular and nationalistic overtones and one in tune with the latest developments of the international avant-gardes. On the contrary, his quest was to reconcile these apparently incompatible camps. He merged both innovative forms with social content to produce one of the most radical experiences in the visual arts from the sixties.

In “Esquema Geral da Nova Objetividade,” Oiticica questioned “how an underdeveloped country could explain and justify the creation of an avant-garde, without it being considered a symbol of alienation, but instead as a decisive factor for the collective process.” For him, the only way to produce a new art was “to create new experimental conditions where the artist takes on the role of ‘proposer,’ ‘entrepreneur,’ or even ‘educator.’” In this essay, he shifts the attention from the artist to the audience, from authorship to collective experience, from production to reception, from product to process.

In 1968, the military dictatorship enacted the Institutional Act #5 (AI-5) to outlaw political opposition, leading to the widespread arrest of leaders who represented different sectors of the civil society. The AI-5 suspended habeas corpus and established censorship of the press. Torture became part of the government’s method of obtaining information on its political opponents. Oiticica left the country in a voluntary exile. In 1969, Gullar lived clandestinely in Brazil for a year, fearing political persecution and was forced to leave the country in exile in 1971.

His “Popular Centers for Culture” had failed both for their lack of aesthetic innovation and for their failure to communicate to its target audience. It was Gullar, himself, who later acknowledged that when the cultural activities of the CPCs were expanded towards the unions and slums, not many workers were interested in seeing the plays of the group. After his return to Brazil, in 1978, Oiticica did not live long enough to see the ramifications of his contribution for this paradigm, but during the vacuum imposed by the military dictatorship, it was out of his “aesthetics of the margins” that Brazilian visual arts had finally found their artistic vocation.

Extremely influenced by each others’ ideas, Gullar and Oiticica provided the fundamental theoretical framework that would shape Brazilian art in the next decades. The relationship between art and politics, so indebted to the discussions from the 60s, became central to the artistic developments that later took place in the country, especially when artists had to face censorship and authoritarianism.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Sixties

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American Press Association fellowship in 1977. Others—journalist Penny Lernoux and photographer Richard Cross—had also committed much of their lives to Colombia, although their untimely deaths were …

The True Impact of the Peace Corps: Returning from the Dominican Republic ’03-’05

I am an RPCV: a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. For me the Peace Corps was an intense life experience, above anything else. As I continue to reflect on it, I am struck with the many and varied ways in which it continues to affect my life. As a PCV in the Dominican Republic from September 2003 to November 2005, I lived, worked, and learned in a small sugar cane-dependent community two hours outside of Santo Domingo…

In the Shadow of JFK: One Peace Corps Experience

I am often asked about the Peace Corps by students and recent graduates. The most frequent questions are, “why join?”, “what did you do?”, and “what has it meant for your career?” Here is my story. My earliest recollection of international curiosity was in the fourth grade when Sister Margaret Thomas described her experience as a recently returned missionary in Bangladesh. In high school, my sister Mary went to Peru on …