At the Center of Things

A Nation From Below

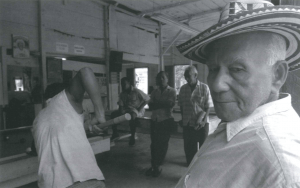

Aracataca was the childhood home of writer Gabriel García Márquez. His autobiographical book Vivir Para Cantarla was just published in Spanish a few months ago and much of the book takes place in Aracataca. Even though Aracataca is in a region with huge guerrilla presence, the town has been left alone in peace. Many believe this is because of the high regard the rebels have for García Márquez.

It would be difficult to imagine the violence in Colombia occurring in the United States. Before the actual formation of the U.S., the first Anglo colonizers were convinced that they could create new spiritual and material lives for themselves in the “New World.” They had separated themselves from the hierarchies of the old social order and in search of liberty, they crossed the ocean never to return. The New England colonizers began forming tiny towns, each one with its small church and one-room schoolhouse, surrounded by little specks of land, which they all worked together. These people thought alike. They rested the Bible on their laps, and read it quietly to themselves. They taught their children that they were the chosen people, for God had picked them to live an exemplary life here on earth and in the hereafter. Each one was to find God within his inner self.

All those who could not conform to the life of these towns, whether because they were deemed to be possessed by the devil or driven by carnal passions or discordant religious convictions, did not fare at all well. They were expelled from their towns, yet they had already been influenced by the settlers’ inherent belief that a little further down the road, on the other side of the river, in the next valley, they would build a new town where they could all think alike and remake their lives in their earthly paradise. And thus, that was how those who were beginning to regard themselves as Americans began to separate themselves. They spilled out across the land, searching within themselves for who they were. Alone, in their own solitary ways, in some new place, they sought the liberty and the self-knowledge which has them traveling to this day, from one place to the next.

In America, the pursuit of happiness, which came to be inscribed in the Constitution, is contained within the individual, but can often not even be found only a few feet away. This is the great paradox of American life. In the United States, the individual goes off in search of his essence, of who he truly is. He penetrates the land. The American ideal from the very first days of this civilization can be found in the virgin wilderness. It is located in the masterless individual, in the self-made man, the self-sufficient person who does not depend on anyone but himself. The individual is prior to society. Here the colleges were almost all built far from the city, so that the youth of this society could go out and commit itself to a spiritual and intellectual experience far removed from the corrosive effects of urban life. Centuries later, during the student movement of the 1960s, only in the United States did thousands of young people become motivated by the search for rural communes where they could live amongst one another with their backs to society.

The United States is the land of the cultural non-conformist, the cowboy, the rebel without a cause. Americans are outsiders. They are provincials. They were and remain a people in search of “a marginal world,” in the words of Bernard Bailyn, the Harvard historian of the American Revolution.

Few Colombians in their right minds would wander off to be at the margins. Hence, it would be very difficult to imagine American violence in Colombia. It is entirely improbable that a Colombian version of Theodore Kaczynski, a criollo unabomber, would emerge. For who in Colombia would wish to go off into the mountains to live in a little hut by himself, year after year, in celebration of poverty and silence, without music, radio and television, without someone to talk and make love to? No Colombian would start sending bombs by mail without anyone knowing he was actually the one sending them. No matter what social class they come from, whether they live in the city or the countryside, or how strong their regional affiliation may be, Colombians seek to be in society, giving and taking, conversing, dancing, and drinking. They want to be at the center of things. They want to be seen, regarded, respected, and honored.

In the long history of the country, there have been no separatist movements of any significance. Back in the 1960s, Conservative Senator Álvaro Gómez Hurtado referred to some emerging areas under guerrilla control as “independent republics,” but there is little evidence that these rural people actually wanted to be independent of Colombia. Many years later, in 1988, when he was kidnapped by the M-19 guerrillas, the most urban of all the rebel groups, Gómez Hurtado got a better sense for what the guerrillas stood for in Colombia. “They insisted on ownership of the land, and complained about the isolation of the campesinos,” the rural people. “They protested,” he wrote in his memoir, Soy Libre, “against the lack of communication, the lack of services, the lack of teachers, and the bad condition of the roads.”

Indeed, the rebels have rarely sought revolution. While they took on a Communist veneer during the Cold War years, more often than not it was the radical urban intellectuals in the late 1960s and early 1970s who were themselves yearning for a socialist future and therefore plastered a revolutionary face on the guerrillas. Colombians, especially those living in outlying areas, are forever complaining that their government does not pay sufficient attention to them. They want to be connected. In contrast, Americans want to be left alone. Colombians are a clamoring people; governing them is certainly no easy matter. Back on May 27, 1964, when the army had already begun its maneuvers around Marquetalia, the most well known of these “independent republics,” a man who was being referred to as “Tirofijo,” or “Sureshot”—the same one who some months later would become the leader of the newly formed Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a position which he holds to this day—sent two of his men to intercept a government road inspector and public health official in order to plead with them to deliver a letter to the governor and the colonel in charge of the region. Tirofijo wanted it to be known that while he would not allow soldiers into the area under his control, he welcomed the civilians who wanted to build a road through it. Furthermore, in his letter, Tirofijo implored the government to build schools and clinics in the area. Much later, in 1999, Tirofijo demanded and received the temporary use of a huge territory around San Vicente del Caguán from President Andrés Pastrana. The rebels wanted the land in order to better connect with Colombia, to gain strength so they could fight and negotiate more effectively with the government.

Since at least 1983, the rebels and the government have been linked with each other by messengers, letters, telegrams, telephones, and emails. They have engaged in off-again and on-again conversations. They have joked together and gotten drunk together. They have traveled through Europe together. The rural rebels have become media stars. They have delighted at seeing their faces in pictures in the newspapers, at being followed around by television crews, and visited by the head of the New York Stock Exchange.

Colombians strive to not be left to themselves. Solitude is a sinking feeling. To be left alone is to be humiliated. Had Gabriel García Márquez’s masterful novel been a century-long fictional history of the United States, it would certainly have recounted the heroic struggles of individuals to successfully carve out lives for themselves in the wilderness. But not in Colombia. Life in the isolated tiny town of Aracataca, in Macondo, was pointless, a hundred years of solitude. Colombians feel that their past has been worth little, for the ideal of all living in harmony together has not been accomplished. Too many Colombians have lived separate, isolated, marginal lives.

It might not be entirely preposterous to suggest that one of the many motivating factors for the guerrillas to kidnap members of society—making Colombia the kidnapping capital of the world—is their desire to see them, relate to them, communicate with their families, experience human anguish together, and make themselves present in the private lives of other fellow Colombians. They can say, “We too are here.” They can converse and deal, hand over their kidnap victim and receive something in exchange: money, a word of thanks, or simply the reputation that they dealt honorably with their captive. Conversely, as they are the ones who have had to live solitary lives out there in the countryside, might it not be that they feel that it is only fair that some urban people live through that lonely experience as well?

Early on, Spaniards were the ones to come to these lands. They established complete societies with a regulating and paternalistic state, and hierarchies in which each person had his place, above some and below others, where people related to one another and were part of a social organism into which they were integrated in unequal ways. In Colombia, individuals have understood who they are by viewing themselves as members of something larger. Hierarchical ties loosened after independence in the early nineteenth century. With the state unable to reach out and regulate the society, especially the countryside, people began to organize themselves together, from the bottom of the society toward the top. Here lies much of the vitality of Colombia. Those from below have struggled to be part of society, often with considerable success, but at other times not. Tirofijo and the rebels did not go out into the mountains to find themselves, but to find the way to be with us, with the city, with the nation.

For a whole half-century now, we in Colombia have not known how to bring them in. This is the great paradox of Colombian life. Seeking to be recognized, those from below reach out, often collectively, only to be turned away.

Back in the early 1950s, when the urban Liberal Party politicians broke off their ties with their rural followers in order to remove themselves from all the rural turmoil, the guerrillas clamored for their lost leaders. “What plans do they have?” Tirofijo exclaimed. “Nothing, silenced….The body just can’t take any more humiliation,” the rebel leader moaned, time and again, decade after decade. For years and years it seemed that there was little the guerrillas could do to keep from being ignored by the government and the society.

Shortly after the army bombed the “independent republic” of Marquetalia in 1964, the emerging guerrilla movement declared that “We were patient, awaiting that the official promises about the respect for life, honor and property be met…After trying to make ourselves known wherever we could, in the national Parliament and before other representative entities, before the high clergy, the National Government, we were not heard. We have now felt obligated to take up arms and to turn ourselves into a guerrilla movement…” In 1965, the FARC were born.

On May 1, 1964, sixteen days before the already announced “great plan of civic-military action” by the army against Marquetalia was set to begin, the newspaper El Tiempo reported that the Cardinal of Colombia, Luis Concha Córdoba, had not given his permission for three of his priests, Monsignor Germán Guzmán, Camilo Torres—the soon-to-be martyred rebel priest—and Gustavo Pérez, to be part of a high-level commission composed of some of the nation’s most notable reform-minded intellectuals, that was to travel to the area to help the government come to an understanding with the rebels. The next morning, the three other commission members—Gerardo Molina, who would become the historian of liberal ideas in Colombia, and Orlando Fals-Borda and Eduardo Umaña Luna, the authors, together with Germán Guzmán, of La Violencia en Colombia, the extraordinary 1962 book on the rural conflicts of the 1950s—declared that the commission could not carry out its duties without the three clergymen’s participation. Bombs fell on Marquetalia. Tirofijo and most of his campesinos escaped.

On November 20, 1992, Gabriel García Márquez and many of Colombia’s most important intellectuals, some of whom were the former radicals who had, after 1965, wished the guerrillas to be something they were not, issued a public statement condemning the rebels for their violent methods and ill-defined goals. In an instant reaction, a journalist in El Tiempo wrote triumphantly that “now it can be said that the solitude of the guerrillas is monumental.” The guerrillas would return to the limelight for a few brief years between 1998 and 2003 during the latest failed peace process in Colombia. They are away again now, but not gone.

Herbert Braun teaches Latin American history at the University of Virginia. He is the author of Our Guerrillas, Our Sidewalks: A Journey into the Violence of Colombia (Rowman and Littlefield, 2nd. Edition, 2003), a memoir of the guerrilla kidnapping of his American brother-in-law in Colombia. A different and longer version of this essay first appeared in Revista Número 29 (Bogotá), June-August 2001.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

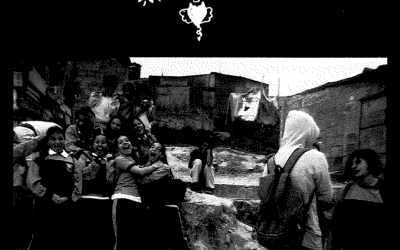

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...