Becoming Latin@s

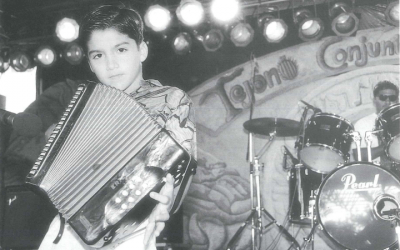

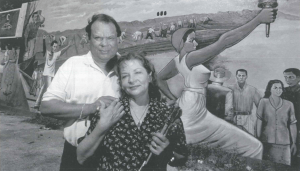

Becoming Latin@s: Creation of New Art and Identities. Photo by Nuri Vallbona.

In California hospitals today, the name most often given to baby boys is José. No wonder there is talk of México’s reconquista of that vast area of the Southwest that it had lost to the United States in 1848. The treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo that officially transferred the territory included what turned out to be precarious provisions of language and cultural rights for residents who changed nationality without moving from home. The difference between treaty and treatment was obvious very soon to all interested observers. Even before the Civil War put an end to Cuban schemes for annexation to the U.S., reformist José Antonio Saco warned that it would mean the end of Cuba as it had meant the end of autonomy for Texas and California, because the U.S. could not tolerate cultural differences.

A generation later, José Martí repeated the warning about Anglo-only intolerance, which would plague Puerto Rico, where English was the mandatory language of instruction for 50 years after the island was annexed through the Spanish-(Cuban)-American War. Puerto Rico’s cultural victory was that it never adopted English (known as el difícil, while the U.S. flag was called la pecosa). And by now, Mexican Spanish is back in California and in Texas (traveling as far as Kansas, where nearly half the Dodge City school children come from Spanish speaking homes) as the result of unstoppable migrations. On the East Coast too, the earlier massive Puerto Rican immigration came to fill labor needs (paralleling the Mexican bracero program to supply workers in the West initiated in the 1940s) is now being matched by immigration form practically everywhere. (Of the top ten “sender” countries in the last decade, four are Latin American and Caribbean: Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Jamaica; in the next 10 are Haiti, El Salvador, Colombia, and Peru.)

Perhaps this time, our safely established country can recover some of the cultural flexibility it lost through homogenizing annexations and through the defensive patriotism that closed German publishing houses and interned Japanese-Americans during WWII. At the level of artistic production and media responses to dramatic demographic change, the U.S.–like other industrialized countries today–is again a land of immigrants eager to improve their lives. Unlike the European democracies facing the immigration dilemma (the Faustian bargain of needing and desiring foreign workers while sharing deep anxieties about the cultural implications of large scale immigration from North Africa, Turkey and Eastern Europe), this country need not insist on a homogeneous heritage to insure its future, but rather on the constitutional freedoms and responsibilities that have traditionally welcomed immigrants as full participants in national development.

During the last few decades, Latin@s (a gender-friendly shorthand) have become a powerful new political, cultural, and economic force. And Census projections now claim that by the year 2050 fully a quarter of the US population will be of Latin@ origin. By then the U.S. will be the only major post-industrial democracy in the world with ethnic minorities constituting nearly half the population. The change feels sudden in a country that, at the end of World War II was largely of European origin. The transformations brought by large-scale immigration, globalization, and transnationalism will require systematic research, policy analysis, and responsible public debate. They will also demand renovation of American Studies in general, and the articulation of a project or projects for Latin@ Studies in particular.

There is a symmetry–that gives some of us aesthetic pleasure–between European immigration in 1900s and Latin American immigration today. During the first decade of the Twentieth Century, 8 million of all immigrants were Europeans. During the decade of the 1980s, 8 million immigrants to the U.S. originated in Latin America. Indeed as the Century came to a close, there has been a complete transformation, a complete shift. Through 1965, 80 per cent of all immigrants in the United States were Canadians and Europeans. Now the vast majority of all new immigrants originate in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia.

We’re looking at a phenomenon that is very recent in terms of its main formations and the dynamics it has generated. Over ninety percent of all Central Americans and Dominicans living in the United States today are either immigrants or the children of immigrants. We may be used to thinking of former Mexican territories, or Caribbean Nueva York (the best thing about the City, so the joke goes, is that it’s so close to the United States), or Cuban Florida. But today, the new immigration is also changing the traditional South: half of all the children are Mexican in Dalton, Georgia schools, home of the carpet industry (which is in the hands of Latin@ workers). In Florida, the Latin@ population increased 42 percent from 1990 to1998. But in Georgia, the Latin@ population increased by 102 percent, and in Arkansas by 148 percent. The South is being transformed by the Latin@ presence. There and elsewhere, it is structured through transnationalized networks of families and communities of origin.

Border controls seem to have more of a performance effect than a preventive function, since many of the apprehended border-crossers try again. They want to come and the U.S. economy continues to thrive on immigrant workers for agricultural, service, industrial, and post-industrial jobs. And though thousands of people are apprehended and deported every day, the stricter controls have a paradoxical effect: Latin@s decide to stay once they get here. Immigration flows today are driven by family reunification, labor recruiting networks, and wage differentials that are difficult if not outright impossible to contain via unilateral policy initiatives.

How do sending nations feel about the massive movements outward? Remittances in no small measure compensate the homelands for their loss of workers. In fact, loud protests against U.S. restrictions on immigration are often heard from Latin American heads of state. Central Americans, the largest number of asylum seekers in the United States in the last two decades, last year sent well over a billion dollars back home–the most important source of foreign exchange in the Salvadoran economy. That’s also true for the Dominican Republic–today roughly 1 of every 6 Dominicans lives in the U.S. In all, more than a hundred billion dollars a year cross boundaries in these international remittances.

Along with the massive immigration with an intent to stay, is the intense circular migration driven by transnational circuits such as the Dominican experience in New York. This transnationality is unlike anything we have seen in previous waves of immigration. With the old pattern of immigration to the United States, a break was made with the country of origin. The Irish, the Eastern Europeans, the Italians either came forever or they went back. Fully a third of the Italians coming to the United States returned home. But they didn’t move back and forth, participating in two economies and two polities, the way many Latin@s do today. These transnational citizens are political and economic actors in more than one country simultaneously. Some observers have noted the outcome of the last Dominican presidential election was determined in New York City, where Dominicans are now the largest group of immigrants.

The U.S. is learning to anticipate cultural difference inside its borders; but just below the surface lay nativist anxieties about the country’s coherence in light of this massive, unprecedented migratory flow–since the 1960s over 20 million new immigrants came to the US and since 1990s the pattern has intensified to nearly a million new arrivals per annum. And while transnationalism flourishes, make no mistake: the vast majority of Latin American immigrants are here to stay. They are arriving in the United States knowing that they want to live here and that they want to stay in the United States. The delicious paradox is that in the era of deep and dense transnational, globalized networks, Latin@ immigrants are establishing deeper roots on US soil than ever before.

Perhaps we can promote the argument that this country needs immigrants not so much for economic needs, but for psychological, symbolic, and cultural reasons. By carving out their own cultural space through Spanish-language media, at the same time that the pull of U.S. culture on the world is stronger than ever, immigrants can keep cultural pluralism in focus, so that political practices do not collapse into mean-spirited and monocultural intolerance.

At this moment in history, when the country is struggling with uncertainty about its ability to culturally withstand the latest wave of new immigrants, ironically American culture is arguably, for better or worse, at its most powerful and influential moment on the world-wide stage. Through new information technologies, the American ethos dominates youth culture, influencing language, street fashions and music throughout vast sectors of the world. From Paris to Katmandu to La Paz youth are wearing hip-hop clothing, watching MTV, and standing in lines to see the same movies. Even prior to the American dominance of international youth culture, the children of immigrants have always tended to gravitate to the characteristics of the new culture. Children quickly acquire the new language skills and often become reluctant to speak their language in public. They desperately want to wear clothes that will let them be “cool” or, at the very least, do not draw attention to themselves as “different.”

Children of immigrants become acutely aware of nuances of behaviors that while “normal” at home, will set them apart as “strange” and “foreign” in public.

While immigrant parents generally acquire some English skills, it is likely that they never really catch on to how different the rules are here. Children of immigrants, on the other hand, are likely to learn the “rules of the game” quickly and easily. There is a powerful centripetal force drawing children into the dominant culture. The parents inevitably struggle with ambivalence. Immigrants are by definition in the margins of two cultures. Paradoxically, they can never truly belong either “here” nor “there.” In 1937, Stonequist astutely described the experiences commonly involved in social dislocations which is as useful today as it was then.

Cultural transitions, he argues, leave the migrant “on the margin of each [culture] but a member of neither.” An immigrant enters a new culture and no matter how hard she tries, will never completely belong; her accent will not be quite right and her experiences will always be filtered through the dual frame of reference. Nor will she “belong” in her old country; her new experiences change her, altering the filters through which she views the world. Stonequist contends that marginality is intensified when there are sharp ethnic contrasts and hostile social attitudes between the old and new cultures.

Immigrants, and most significantly, the children of immigrants–the new Latin@–respond in different ways. Some chose to mimic and identify with the dominant culture. Sometimes this identification with the mainstream culture results in weakening of the ties to members of their own ethnic group. These young people all too frequently are alienated from their less enculturated peers; they may have little in common or may even feel they are somewhat superior to them. While they may gain entry into privileged positions within mainstream culture, they will still have to deal with issues of marginalization and exclusion. Other children of immigrants develop an adversarial stance constructing identities around rejecting-after having been rejected by-the institutions of the dominant culture. Those who forge bicultural identities develop cultural competencies well suited to transverse cultural boundaries. These youth code-switch with ease in the linguistic, interpersonal, and cultural realms. They seem well posed to take advantage of today’s globalized, internationalized economy and culture.

Latin@s today are making choices as never before. They are not only replicating lifestyles, but inventing new ones, which have an impact on the dominant culture. Instead of lamenting, with Nuyorican Sandra María Esteves, that her embattled boricua identity is “Neither Nor” as she describes herself in a poem, some contemporary transnationals experiment by pushing English grammar into the “either and” possibilities. Esteves’ compatriot, Tato Laviera calls himself “AmeRícan,” syncopating the accent to favor Rican, and performing an aplatanado version of America as an update for apple pie.

Marcelo Suarez-Orozco, a professor in the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and Doris Sommer, a professor in Harvard’s Romance languages and Literatures Department, co-teach the Latino Cultures course.

Related Articles

Forum on U.S. Hispanics in Madrid

The Trans-Atlantic Project, an academic initiative to study the cultural interactions between Europe, the U.S. and Latin America has been invited by Casa de América, Madrid, to present a …

Cuba Study Tour

Waiting at José Marti International Airport for the first Harvard students to arrive for January’s DRCLAS Cuba Study Tour, my companion, a theater critic at Casa de las Américas, commented to me …

The Soulfulness of Black and Brown Folk

And so, by faithful chance, the negro folksong – the rhythmic cry of the slave – stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience …