Between Drug Gangs, the Police and Militias

An Anatomy of Violence in Rio de Janeiro

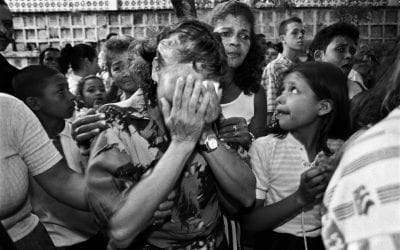

On June 27, 2007, 1.350 troops from the civil and military police and the newly constituted National Security Force invaded a conglomeration of favelas known as the Complexo de Alemão in Rio de Janeiro’s Zona Norte. By the time the operation ended, nineteen civilians lay dead. The invasion was swiftly and loudly condemned by human rights organizations that accused the government of killing and injuring scores of innocent victims. The government insisted that the victims were members of an organized crime faction that was waging war on public authority, a war that could not be won without bloodshed.

Organized crime factions first emerged in Rio in the early 1970s, when the military dispatched political prisoners to a penitentiary on the island of Ilha Grande. These prisoners impressed upon a group of common criminal detainees the advantages of solidarity, organization and discipline. The product of this unlikely encounter was the Comando Vermelho. Initially, the Comando Vermelho sought to impose its control over Ilha Grande and other prisons in the system. Eventually, however, the reach of the Comando Vermelho extended beyond the prison system’s walls to clandestine cells that conducted bank robberies and kidnappings to finance the purchase of weapons and the escapes of their incarcerated colleagues. Then, around 1982, the decision was made to finance the Comando Vermelho’s activities through the drug trade.

The Comando Vermelho’s decision to become involved with the drug trade led to a period of intense warfare for control of Rio’s favelas, where most of the distribution points for drugs are located. Many of the leaders and rank and file members of the Comando Vermelho were from the favelas, and so the relationship between these areas and drug trafficking naturally followed. And the illegal, haphazard and impenetrable nature of most favela neighborhoods provided the perfect terrain for drug gang operations.

The ability of the Comando Vermelho to operate in Rio’s favelas depended on the relationship between each drug gang and the community within which it was embedded. Drug gangs rely on the local population to provide new recruits and to protect them from the police. It became increasingly common, therefore, for drug gangs to provide social services and to finance public works. It also became increasingly common for drug gangs to take advantage of the absence and widespread mistrust of public authorities to lay down the law and punish those who caused trouble or disobeyed orders.

Over the course of time, the Comando Vermelho split into various loosely organized factions, the most significant being the Terceiro Comando and the more recently established Amigos dos Amigos. These factions compete militarily for a share of the drug market in Rio that continues to bring in millions of dollars in profit each week. And it is this competition, more than anything else that has transformed not just a select few neighborhoods, but also an entire city, into a war zone.

The police in Rio have responded to the emergence of drug gangs and drug gang factions with extreme violence and have been killing, on average, one thousand civilians each year for the past few years. Most police victims have no criminal record or involvement with crime whatsoever. They are killed simply because they are male, young, dark-skinned and poor. Occasionally, international outrage over police brutality in Rio forces state authorities to intervene. The effect is always temporary, however, and it is not long before the number of civilian deaths at the hands of the police begins to rise.

A number of factors make the prevention of police homicides difficult. The first is that the investigation of the crime scene is often in the hands of the police. The second is that the police always claim that they are acting in self-defense and that extrajudicial killings are the outcome of shootouts with well-armed criminals. The third has to do with the widespread use of unregistered and unauthorized guns. It has been common practice for police in Brazil to plant guns on their victims to corroborate claims of a shootout. And, finally, bodies are often removed to local hospitals to create the impression that the police tried to assist their victims and to compromise investigations of the crime scene.

There have also been institutional factors that have made the investigation and prevention of police homicides difficult. Until recently, the military police in Rio have been encouraged by their superiors to eliminate criminal suspects, rather than arrest them. In the mid- to late-1990s, police officers were given pay raises and promotions for killing urban youth. Also until recently, military police tribunals were responsible for investigating crimes committed by the military police and could be counted on to determine that civilians were killed in acts of self-defense.

In 1996, the situation appeared to change somewhat with the implementation of Brazil’s first Human Rights Plan, which transferred oversight, and jurisdiction of police homicides to civilian authorities. Even so, it is up to the police to determine what is and isn’t a homicide, and the military police retain the right to “oversee” such cases. Furthermore, civilian witnesses of police brutality are routinely threatened and discouraged from testifying, and few prosecutors have the time, resources or political will to conduct their own investigations. And, because the judicial system in Brazil is so overburdened and inefficient, changes in the oversight and processing of police crimes have had little effect.

Furthermore, widespread support exists for extrajudicial police action among the general population. Death squads comprising of off-duty and ex-policemen are often hired by local merchants to clear the streets of “undesirables” and are responsible for killing a large number of Brazilian youths each year. This should not be seen as an endorsement of the police, however. Few Brazilians make use of the police who are perceived as untrustworthy and violent. It is more an indication of how far the situation has deteriorated. The problem is that in recent years drug-related violence has spilled out beyond thefavelas into all areas of city life. And it is within this context of generalized violence and fear and the breakdown of public law and order that calls for the extension of human rights to police victims have fallen on deaf ears.

Finally, and most significantly, while it may appear on the face of it that the police in Rio have been waging war against the drug trade in order to shut it down, nothing could be further from the truth. The police in Rio have profited from drug trafficking from the beginning and continue to be involved at every level, from the transshipment of drugs across national borders to providing protection for drug gang faction leaders. Unfortunately, despite innumerous crackdowns on illegal police behavior and the large number of legal proceedings that have been brought against the police it is still proving extremely difficult to purge criminal and corrupt elements.

The question is, is it simply a matter of rooting out the occasional bad element? Or are the police so intimately involved with organized crime—and dependent on violence for their livelihood—that nothing short of a completely dismantling and rebuilding the force will suffice? The other question is, what happens to the police when they are expelled? Many, it turns out, are reinstated and go on to commit more crimes. Others end up in the pay of drug gangs, often as military advisers. Alternatively, they join forces with the estimated 600 to 1,000 firemen, prison workers, active duty and retired policemen who constitute the militias that are gradually and inexorably—it would seem—taking over the favelas of Rio’s Zona Oeste.

These militias, otherwise known as polícia mineira, act much like the gangs they aim to replace in that they promote parties and cultural events and provide legal and medical services via each community’s neighborhood association. They also charge protection fees and make money from the sale of cooking gas and from taxes levied on real estate transactions and money lending. The only difference between the militias and the gangs they replace is that they kill or expel and confiscate the property of anyone suspected of being associated with drug trafficking.

Many of the residents of these areas express relief to be out from under the control of drug gangs. They are acutely aware, however, that they have traded one authoritarian and unaccountable force for another. And to be honest, they have little or no choice in the matter. As one policeman who offered such services said: “We are a necessary evil. The residents oftentimes don’t want us here, but end up agreeing because they need to free themselves of violence.”

The question is, if the uniformed and on-duty police can get away with killing around thousand civilians yearly, what possibility or mechanism is there for overseeing and controlling what is becoming the extra-legal arm of an already deadly public security force? As in other countries of Latin America, there is the strong suspicion that militias operate with the implicit approval of public authorities. After all, the ninety or so neighborhoods that are currently under the control of militias in Rio are never subject to the type of incursion that is typical of police operations in favelas that are dominated by the organized gang factions, despite the similarities between them, leading some commentators to suggest that what we are seeing here is a military-inspired campaign to retake and hold, by whatever means necessary, territories that have been lost to the state.

A few days after the invasion of the Complexo de Alemão, the federal government announced plans to invest 3.8 billion Reais (U.S. $2 billion) in the state of Rio, including 1.6 billion that was earmarked for Rio’s favelas. Then, a few weeks later, the federal government unveiled plans for a National Program of Public Security and Citizenship (Pronasci) that will spend 6.7 billion Reais ($3.7 billion) over the next five years on 650,000 individual grants of between 100 and 300 Reais ($57 to $170). Modeled on its highly regarded social assistance program, Bolsa Família, these grants will be distributed to at-risk youth, low paid policemen and women, prison workers, army reservists, and women in positions of leadership in areas of high conflict. Both programs represent an explicit attempt to extend the reach and influence of the state and to compete with organized crime.

The question is to what extent will these programs be successful? This is by no means the first attempt to urbanize Rio’sfavelas. Indeed, since the transition to democracy in the early 1980s, there has been any number of programs designed to improve the infrastructure of such areas. And, as a result, the majority of the inhabitants of the favelas now have access to running water, sewerage and electricity. This does not mean, however, that the favelas have been integrated into mainstream city life or that the distinction between the worlds of the asfalto and the morro has been abolished, far from it. People who live in a favela still have to lie about where they live and most middle- and upper-class residents of Rio wouldn’t dream of setting foot in such places. Furthermore, programs that invest resources in drug-gang dominated areas of the city do not effectively ‘compete’ with organized crime. On the contrary, they tend to be ‘captured’ by criminal elements and used to consolidate their hold over such areas.

It is also questionable whether a program of small grants will stem the flow of former military and police personnel and poor youth, in particular, into the ranks of organized crime. Until there is a public education system in place that provides real possibilities for social advancement, and formal sector jobs are made available that pay decent wages, there will be little to persuade poor teenagers in Rio to stay the course. In fact, it’s amazing that so few youths join the ranks of organized crime, given the conditions of slave labor and outright discrimination that they face on a daily basis.

Winter 2008, Volume VII, Number 2

Robert Gay is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Toor Cummings Center for International Studies and the Liberal Arts at Connecticut College. His research focuses on democracy, civil society and violence in Brazil. He is the 2007-08 Lemann Visiting Scholar at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

Related Articles

Escuelas de Perdón y Reconciliación

Escuelas de Perdón y Reconciliación Un proyecto de la memoria en AméricaLa geografía del continente americano está atravesada por relatos de violencia, de dolor y de injusticia. La memoria ingrata en el recuerdo de pueblos, culturas y personas, amerita propiciar...

The Symbolic as Strategy

It is now more than a decade since Peru suffered devastating political violence, which left about 70,000 dead. Years have passed since the Report of the Commission of Truth and…

Justice For All

In January, 2007, Mexican president Felipe Calderón ordered the Federal Army to the southwestern state of Guerrero. The order was part of his plan to rein in crime and corruption…