Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

What Is Different?

Photos by Mauro Arias @mauroariasfoto

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador.

I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad several times when he returned home at the end of the day: “Tell me, did those communist guerrilleros stop you today?” and my dad used to answer: “No, the muchachos (the boys), they didn’t stop us and they didn’t do anything wrong.”

My mother was convinced that if the Farabundo Martí Liberation Front (FMLN) guerrillas won the war, El Salvador would become like Nicaragua or Cuba. In contrast, my father always expressed a more progressive political point of view: he felt a sense of empathy for the guerrilla; I guess he believed they were fighting for a legitimate cause.

These family conversations led me to constantly wonder what the differences were between this so-called left and right that made my parents differ so much in their political views. What were both sides—and their international allies—really fighting for? What values were they supposed to be defending?

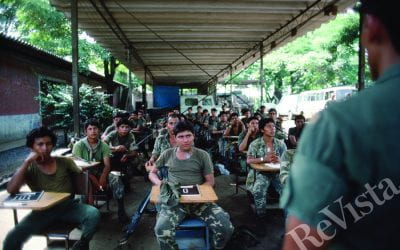

I believe our conflict was largely viewed as part of the Cold War; after all, in 1981, former U.S. Secretary of State Alexander Haig recommended increasing military assistance to El Salvador to “draw a line” against the Soviet communist advance in Latin America.

Peace accords were signed in 1992, and after 20 years of consecutive right-wing ARENA party governments, the first left-FMLN government was democratically and peacefully elected in 2009. After decades of speculating about what changes the left would bring to our country, we finally were witnessing a major transition. Time had finally come to contrast right- and left-wing policies in El Salvador in practice.

Now, after more than six years of the left in power, what is different in El Salvador? In my opinion, not that much has changed. Indeed, the left-wing government so far seems to have more similarities than differences with its right-wing predecessor—particularly with the last ARENA administration. For the last six years, the FMLN government has delivered orthodox left-wing rhetoric, while at the same time continuing with most economic and social policies from the previous right-wing governments. Many Salvadorans are disappointed; others are relieved; and some others think the lack of radical acts is just a façade, and that the risk of becoming a Venezuela or Cuba-style country is still real. What are the manifestations and consequences of this continuity? And why have there not been major changes?

With 103 homicides per 100,000 citizens, in 2015 El Salvador became the most violent country in the Western Hemisphere. Almost 6,700 Salvadorans were killed in 2015, and as I’m writing this article in the first days of 2016, on average 24 people are being assassinated every day. Our death toll is nowadays as high as it was during the civil war years. Crime and violence has become the theme that overshadows all other topics: it is present in every single public policy discussion in our country and in our everyday life; it is considered by almost everyone as the obstacle that if not tackled, will erode any social or economic investment. Moreover, violence has probably become the main driver of migration.

Despite escalating violence, the policies implemented by the left have not been substantially different from those carried out by previous right-wing governments. The FMLN government continues to prioritize symbolic short-term actions with no measurable long term impact. Moreover, it has failed to articulate a strategy to systematically address the root causes of violence and other social problems. The persistence of political polarization has impeded reaching agreements with the right-wing opposition—ARENA—in key issues such as the security strategy.

The left’s most daring foray into controlling violence was a truce with the gangs initiated by the first FMLN government of President Mauricio Funes in early 2012. However, the country’s second FMLN administration under President Salvador Sánchez Cerén in January 2015 repudiated the truce. The press had revealed that—with the complicity of President Funes—gang leaders secretly received concessions during the truce in exchange for a covert pact to curtail homicides, mainly among gang members. To say the least, it was a shady and unsustainable deal and one that many believe only helped to strengthen the gangs. Once the truce officially ended, homicide rates immediately bounced back. Since then, the government has reacted by escalating repression and increasing taxes for additional resources to combat crime and violence.

Economic policy is another area where little has changed. From the beginning, the FMLN government announced it would maintain dollarization, one of the most emblematic economic legacies of the ARENA administrations.

Although the government’s official discourse is more supportive of small and medium enterprises than large firms, the government has tried to maintain close relations with the most important businessmen in the country. Nevertheless, new taxes, public verbal scolding of the private sector, the generalized perception of increased bureaucracy that undermines the business climate and rumors of a potential reform to the private pension system have created constant and increasing frictions between the government and the business community in El Salvador. Although the government claims that it has created dialogue spaces in which private sector participation is encouraged, a constant criticism is that thus far such spaces have not brought tangible results.

These tensions—and crime and violence—may have provoked a larger impact on investment climate than the actual economic policies implemented over the last six years. Moreover, although ideologically the FMLN government is aligned with Venezuela and its Chavista revolution, in practice—and for practical reasons—it has kept close ties with the U.S. government. In fact, El Salvador is one of the four countries worldwide that belong to the first set of the Obama administration’s Partnership for Growth initiative. In 2014, El Salvador entered into a second agreement with the MCC (Millennium Challenge Corporation) aimed at reducing poverty through economic growth.

One relevant economic change is that over the last years the government has gotten bigger. Since 2009, government income has increased 40% and public sector employment has grown by more than 33,000 people. Although government size is not bad or good per se, and a fiscal analysis is beyond the scope of this essay, there is widespread and increasing concern regarding the sustained increase in public expenditure and public debt. The deterioration of the fiscal situation has led to the downgrade of El Salvador in the international credit ratings.

The last ARENA administration introduced transfer programs aimed at poor households (free seed packages, lunch for children at public schools and conditional cash transfers). The FMLN government has expanded those programs, although they’re still modest, compared—for example—to generalized subsidies. But besides these unilateral transfers, there have not been major changes in the implementation of social policy. El Salvador continues to be a country with very low levels of human capital, far from the aspirational discourse of equality of opportunities. On average, Salvadorans have fewer than seven years of schooling. Research on educational quality shows that our country is among the worst performers in international standardized tests.

There have not been substantial efforts to change this reality. Most poor Salvadorans believe that migrating to the United States is their only opportunity to escape poverty and violence, and help the families they leave behind.

Many expected that a left-wing government would be more committed to combat corruption, but that didn’t happen. The institution in charge of supervising transparent use of the public funds (Corte de Cuentas) continues to be irrelevant, and the government recently promoted a law that would limit the capacity of the judiciary to investigate illicit enrichment of public servants. Impunity is not exclusive to the left; it has been an endemic and entrenched characteristic of those in power in our country. Definitely, this hasn’t changed. Nonetheless, is worth mentioning that thanks to the involvement of civil society, access to public information has improved over the last years.

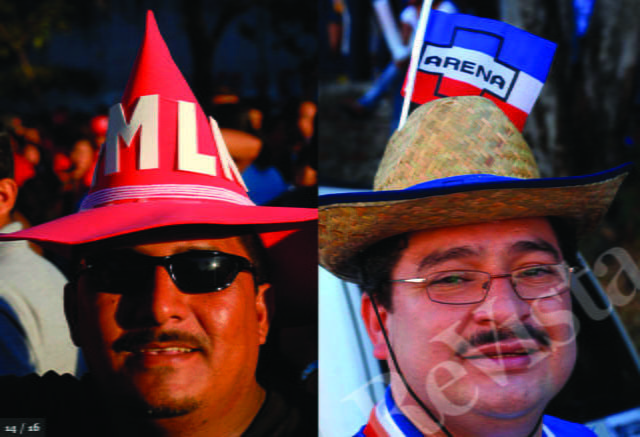

El Salvador is one of the few countries in the continent with a strong bipartisan tradition—like the United States—which means that for better or worse, the way to gain political power in our country is through the two major parties, ARENA and FMLN. This two-party system has its pros and cons: it provides stability, but it also concentrates power in the party elites and perpetuates polarization. Both parties have been chronically reluctant to advance the necessary reforms to increase internal democracy. ARENA—probably because of losing the two last presidential elections—has taken some initial steps to become a more open party. We’ll hopefully see the same trend in the FMLN in the coming years.

Finally, the FMLN has adopted the autocratic vices of former ARENA administrations. It has passed laws in the Congress in a non-democratic manner (by “negotiating” with congressmen and minority parties in order to get the necessary votes for some laws, it has passed laws “overnight” without the proper analysis and discussion); it has continued selecting key officials and negotiating with them on the basis of political calculations, instead of merit.

Why has so little changed? It’s mostly because the margins of maneuver of our small, open and fragile economy are very limited. This narrows the policy alternatives of any government. In addition, there has been a tendency to prioritize short-term policies, instead of pursuing structural long term reforms.

Thus, the definition of “left” and “right” has become more aspirational than practical in El Salvador. Unlike other left-wing governments in Latin America, our leaders lack the economic resources for pursuing an autonomous agenda.

Nevertheless, exaggerating the differences continues to be a useful strategy for both parties. Moreover, since the FMLN and ARENA are finding it difficult to articulate a clear narrative of what they propose, they instead rely on a strategy of discrediting one another. They define themselves not by what they are, but by what they are not.

This strategy appeals to the extremes of each party. In El Salvador, about one third of voters are unconditional FMLN supporters, and a similar percentage is unconditionally loyal to ARENA with the rest being swing voters who usually vote based on specific proposals and results, rather than Cold-War rhetoric.

As a Salvadoran, my invitation to my fellow citizens is to become part of this third group—of the group that can force the two parties to go from the pamphlet right-versus-left discourse to a more pragmatic approach in which finding and implementing solutions to the critical needs of people and to specific problems is at the center of the national discussion. Although we all may have an ideological preferences, we cannot be uncritical of the propositions of the parties that are supposed to defend those ideologies.

To the extent that this swing group grows, the parties will have to reshape their out-of-date narratives. Besides, the evidence has shown that, to a great extent, the behavior of both parties when in power is not that different: they both display autocratic tendencies and cronyism, and they both exploit political polarization to their advantage. They both also have great people, truly committed to the development of El Salvador.

Is one party promoting more democracy than the other? Do their policies aim at strengthening our institutions? Are they focused on implementing long-term programs for enhancing human capital and facilitating equality of opportunities? Are they truly commited to combating corruption? All these questions nowadays are much more important and have more content than simply asking: are they pursuing right- or left-wing policies?

Thirty years have passed since I started wondering what was the true meaning of left and right in El Salvador. Now I understand that in spite of different aspirations and values, reality has limited the ability of the left to depart from previous ARENA administrations. This provides a unique opportunity for our society to adopt a less ideological and a more pragmatic approach to our most pressing problems.

This will definitely require the evolution of both ARENA and FMLN—an evolution that will be driven by more conscious voters who are no longer beholden to the traditional right-left propaganda.

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Carmen Aída Lazo is the Dean of Business and Economics at ESEN, El Salvador’s foremost business university. She received her Master’s from the Harvard Kennedy School Master in Public Administration/International Development Program in 2005.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

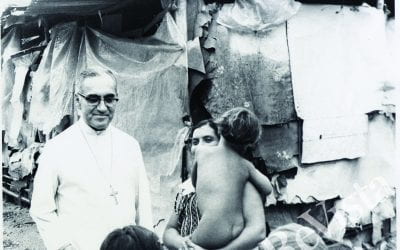

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…

The Salvadoran Right Since 2009

English + Español

In 2009, as the FMLN celebrated its long-awaited first foray into the Casa Presidencial, El Salvador’s largest conservative party—the Nationalist Republican Alliance (Alianza Republicana…