After the Referendum

Reading the Defeat

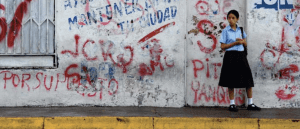

Photograph by Meredith Kohut/CHIRON PHOTOS

On December 2, 2007, Venezuela voters rejected President Hugo Chávez’s proposed constitutional reform. That reform, broadened by the National Assembly to encompass a total of 69 articles, would have led Venezuelan society at an accelerated pace towards “socialism of the 21st century.” With 94% of the results reported, the National Electoral Council’s second bulletin announced that slightly more than half the voters had chosen “NO” in opposition to the Chávez proposal. The specific vote was against “Bloque A,” a proposal that combined the Chávez proposal with a number of the National Assembly measures. The vote against Bloque A came to 4.521.494 votes, 50.65% of the total, as opposed to 4.404.626 votes (49.34%) in favor of “SI.” The difference between the “NO” and “SI” votes was 1.31 %. In Bloque B, an option that included all the National Assembly reform proposals, the difference was slightly higher.

To put the situation in perspective, the vote in support of the Bolivarian revolution had declined 14 %, almost three million votes, from the 2006 presidential elections. The opposition increased its share of the vote by only 211,000 votes. More than a triumph for the opposition forces, the vote was a defeat for the forces of Bolivarianism, opening a political game with uncertainties and contradictions.

How To Read The Defeat

In their first reactions, Chávez’s close supporters reflected uneasy concern and unbridled emotions. However, the president and his allies are now reading the election in a way that has begun to express itself through concrete actions. These measures increasingly point to the idea of recovering lost support through a strategy which, while not essentially altering the goal of advancing towards the model of socialism proposed last year, in tactical terms, includes some actions and words of moderation and political aperture.

For example, on December 31, Chávez granted pardons and signed a broad amnesty law that ceased to press charges against the majority of those involved in the 2002 and 2003 insurrectional activities. Changes were also made to the cabinet in the areas of security, food administration, housing, communications and liaisons with popular organizations, areas that had been weakened and had thus affected electoral results. These changes appeared to respond to a quest for more efficiency rather than signify a modification of government policies.

On January 6, Chávez introduced what he called “the three R’s policy”: revision, rectification and re-impetus. He called upon his grassroots supporters to prepare themselves for the governors’ and mayors’ elections next month (November) and declared that the candidacies “should arise from the decisions of the grassroots base and not as a product of meetings in clandestine smoke-filled rooms, agreements of one party with another, to be finally stamped with the Chávez seal of approval” (El Nacional, June 6, 2008).

That same day, Chávez also announced the relaunching of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela/PSUV) through preparation of its foundational congress. He also proposed reviving the Polo Patriótico, the coalition formed in 1998 for his first presidential election, as a signal that he was resigned to the permanence of other parties in his political platform, a measure to which he had been aggressively opposed throughout 2007, when he pressured his allies to dissolve their membership in other political parties or risk exclusion from the government. He now explained that he wanted to encourage “a grand alliance, not only of revolutionaries” in order to “attract the business sectors, the middle class, who are the essence of this project.” He said that all sectors had to be welcomed into the alliance and that sectarianism and extremism had to be fought “because the revolution has to open itself up.”

On January 11, the president gave his 2007 State of the Union address to the National Assembly, in which he presented the most significant statistics of what he considered his outstanding achievements in his nine years in power (statistics published on the website www.aporrea.org and in the newspapers El Nacional and Últimas Noticias). Towards the end of his speech, Chávez alluded to the three roles that he had played since coming to power, and formulated a self-evaluation of each of those roles. These reflections seem to reveal his own reading of his defeat and how he plans to make a comeback.

He considered his performance as chief of state as positive. From his perspective, this dimension encompasses actions to situate Venezuela firmly on the international stage. In this context, he enumerated initiatives such as ALBA, Petrocaribe and other efforts to strengthen Caribbean and Latin American integration. He also expressed satisfaction with his role as leader of the revolution. He considered that socialism had been sown in Venezuela and nothing would hold it back. He declared that the revolution had been made peacefully, respecting human rights and cultural diversity, with a predilection for dialogue and appreciation for participatory democracy. Where he said he displayed weakness was in his role as head of government.

Chávez talked frankly about what he considered the multiple defects of his government. He mentioned insecurity, food shortages, lack of planning, the bad situation in the jails, impunity, corruption and the sluggish bureaucracy of public administration. All of these defects—he recognized—were making people lose confidence in the government. But Chávez did not talk about the perverse political polarization that has persisted throughout these years, with its heavy burden of intolerance towards his political adversaries and domestic dissidents that was readily fomented by his confrontational discourse.

He also failed to indicate a recognition of opposition sectors that have come to accept the rules of the political game, asking for a dialogue with the government. This opposition, which has made efforts towards unification and, at the same time, to separate themselves from the anti-democratic actors of the past, includes middle-class professionals who could help to contribute to the elevation of political quality of the present democracy, as well as to the improvement of the debilitated and inefficient public sector. But pluralism has not been a value for the president, and polarization has paid off. It seems that he still is not prepared to abandon his policy of polarization.

In general, then, the speech, delivered a month after his defeat, reveals the conclusions that the leader had reached during that period. He seeks to recuperate his losses in 2008 through more efficient administration, but without changing his basic goal of socialism. One example of this is his promise to call for a revocatory referendum in 2010 against himself, if the opposition does not do so, with only two questions: 1) Are you in agreement that Hugo Chávez should keep on being president of Venezuela? 2) Are you in agreement with a small amendment to the constitution to permit indefinite reelection? (linking the two questions), as described in Últimas Noticias on January 13, 2008.

Some Actions

The ideas that Chávez formulated after his defeat in the constitutional referendum allow us to understand some of his recent actions. In foreign affairs, for example, they explain his ongoing conflictive stance toward the United States and Colombia. During his presentation of his annual report to the National Assembly, he publicly asked Colombian President Álvaro Uribe’s government to grant belligerent status to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Army of National Liberation (ELN), a recommendation that provoked strong tensions in the following days with the neighboring country.

This request had the effect of canceling out the positive international impact that Chávez had obtained the previous day when, for the first time in years, the FARC agreed to liberate a group of hostages. The clumsiness with which Chávez made the request to the National Assembly contributed to an increase in Uribe’s popularity in Colombia in the following weeks. Chávez’s demand did not receive the backing of any Latin American country, not even Cuba. In March, after the Colombian Army attacked a FARC camp in Ecuadorian territory, Chávez also made a series of declarations that could have been interpreted as favorable to the guerilla group. Following conversations with other Latin American governments, the president softened his tone and his antagonism, permitting the Group of Rio and the Organization of American States to register a victory over the forces in the region that seek to torpedo Latin American integration and enhance bellicose tendencies.

In regards to the PSUV, the latest decisions suggest only weak modifications to strengthen the collective and democratic dynamic. Congressman Luis Tascón, considered a member of the extreme wing of Bolivaranism, was expelled first from the Block for the Change of the Assembly ( Bloque por el Cambio de la Asamblea) and later from the organization that evolved into PSUV. His expulsion came about as a result of complaints he had made to the Assembly’s Oversight Commision about irregularities in David Cabello’s performance in the Ministry of Infrastructure. Cabello, along with some family members, is part of the group that is closest to Chávez and is considered by the leftist currents within Bolivarianism to head up the “endogenous right.” Assembly President Cilia Flores criticized the fact that Tascón made his complaints in a public space and to the media.

At the same time that it tried to silence Tascón’s accusations, the Foundational Congress of the PSUV, meeting in Caracas in February, approved a mechanism based on an election for delegates to select the party’s national leadership. In addition, another slate was introduced in which presidential preference significantly reduced the list of candidates before the delegates’ election. Even so, the election of the PSUV National Directorate gave Bolivarianism a relatively legitimate and grassroots collective channel based on party militancy.

Some Final Words

November’s regional and local elections will be an important barometer to determine whether the strategy of the president and his allies has worked to recover his strength or, conversely, has led to the continuation of the decline of his force. Meanwhile, the government is increasing its efforts to achieve a steady food supply, above all in the area of staples such as milk, bread and rice, which had experienced shortages in the marketplace because of a combination of factors, including lack of planning and inefficiency and insufficiency of the agricultural development policy. Venezuela continues to import close to 70% of everything that is needed to feed and clothe its population. At the same time, polls in recent years indicate that the popular sectors have increased their consumption as a result of a more effective distribution of the petroleum-derived income through missions and other public policies. However, today as yesterday, this is only sustainable through oil income, the highest per capita that Venezuela has received in its entire history, according to Asdrúbal Baptista in Bases cuantitativas de la economía venezolana (Caracas, Fundación Empresas Polar, 2007).

In this sense, the Bolivarian revolution revives once more the “magical state” which for much of the 20th century maintained illusions about a modernization that was sustained only through the surplus that the oil industry extracted from the international energy market, without any domestic counterpart (Fernando Coronil, The Magical State, Chicago University Press, 1997). Now it finances a vague “socialism.” When this income drops for some reason, or is thought to be insufficient, Venezuela returns to its real situation: a country with resources but without capacity to create wealth. Thus the fantasies collapse. To conclude, a chart that illustrates how, in structural terms, almost ten years of Bolivarianism have not been able to build an economic structure that avoids repeating the same vices of the past: from the mid- 1950’s, production and consumption do not have any relationship with each other. The gap between the two is satisfied by the oil income.

Venezuela pos referendum

Leyendo la derrota

Por Margarita López Maya

En perspectiva comparada, el voto en apoyo al bolivarianismo sufrió una merma de 14 puntos porcentuales, casi 3 millones de votos, con respecto a los resultados electorales de la contienda presidencial de 2006. La oposición, por su parte, aumentó su votación en apenas 211.000 votos. Más que un triunfo de las fuerzas opositoras, fue una derrota de las fuerzas del bolivarianismo, que abrió un juego político que muestra incertidumbres y contradicciones.

Pasadas las primeras reacciones, que reflejaron desconcierto y emociones desbordadas en el seno del chavismo, la lectura que el presidente y sus aliados comenzaron a hacer se ha ido expresando en acciones, que apuntan de manera creciente a la idea de recuperar los apoyos perdidos a través de una estrategia que, aunque en lo esencial no altera el objetivo de avanzar hacia el modelo de socialismo propuesto el año pasado, en términos tácticos incluye algunas acciones y palabras de moderación y apertura.

El 31 de diciembre, Chávez otorgó indultos y firmó una amplia ley de amnistía por la cual fueron liberados de juicios la mayoría de quienes habían participado en las acciones insurreccionales de 2002 y 2003. También hizo cambios en su gabinete, que parecieron obedecer, más que a una modificación en la orientación de las políticas gubernamentales, a una búsqueda de mayor eficiencia en la gestión en las áreas de seguridad, abastecimiento alimentario, vivienda, comunicaciones y relaciones con las organizaciones populares, que fueron debilidades de la gestión que afectaron los resultados electorales.

El 6 de enero, Chávez presentó lo que llamó “la política de las tres R”: revisión, rectificación y reimpulso. Conminó a sus bases a prepararse para los comicios de gobernadores y alcaldes a celebrarse en noviembre de este año e indicó que las candidaturas “deben venir como producto de las decisiones de las bases populares y no como producto de reuniones en conciliábulos, acuerdos de un partido con el otro, y al final el dedo de Chávez”[1].

Ese mismo día, Chávez también anunció el relanzamiento del Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV) a través de la preparación de su congreso fundacional. Planteó revivir el Polo Patriótico, la coalición formada 1998 para su primera elección presidencial, en señal de que se resignaba a la permanencia de otros partidos en su plataforma política, a lo que se había opuesto agresivamente a lo largo de 2007, cuando presionó a las fuerzas aliadas para que se disolvieran so pena de excluirlas del gobierno. Explicó que se debía dar “una gran alianza, no sólo de los revolucionarios”, pues había “que atraer a sectores empresariales, la clase media, que son la esencia de este proyecto”. Dijo que hay que dar la bienvenida a todos los sectores y hacerle la guerra al sectarismo y al extremismo, “porque la revolución tiene que abrirse”.

El 11 de enero, el presidente presentó ante la Asamblea Nacional su informe de gestión de 2007. En su discurso exhibió las cifras más destacadas de lo que consideró sus logros en los nueve años que ha venido gobernando[2]. Hacia el final, Chávez aludió a los tres roles que, según consideró, ha venido desempeñado desde su llegada al poder, y formuló una auto evaluación de cada uno de ellos. Estas reflexiones parecen revelar la lectura que ha hecho de su derrota y cómo piensa remontarla.

Su desempeño como jefe de Estado fue considerado positivo. Desde su perspectiva, esta dimensión comprende acciones para colocar a Venezuela en el escenario internacional. En ese sentido enumeró iniciativas como el ALBA, Petrocaribe y los esfuerzos realizados en pos de la integración latinoamericana y caribeña. De su rol como jefe de la revolución también se mostró satisfecho. Consideró que el socialismo está sembrado en Venezuela y que ya nada lo detendrá. Según dijo, la revolución se ha hecho en paz, respetando los derechos humanos, con respeto a la diversidad cultural, predilección por el diálogo, valoración de la democracia participativa. Pero donde encontró debilidades fue en su rol como jefe de gobierno.

Chávez habló con crudeza de lo que consideró los múltiples defectos de su gobierno. Mencionó la inseguridad, el desabastecimiento, la falta de planificación, la situación en las cárceles, la impunidad, la corrupción, la pesadez burocrática de la administración pública. Todo ello –reconoció- ha venido haciendo perder la confianza del pueblo en su gobierno. Pero Chávez no habló de la perversa polarización política que ha persistido a lo largo de todos estos años, con su carga de intolerancia hacia los adversarios políticos y hacia la disidencia interna, de la cual su discurso confrontacional es un permanente estímulo.

Tampoco mencionó nada que pudiera indicar un reconocimiento a los sectores de la oposición que han venido aceptando las reglas del juego político y solicitando un diálogo con el gobierno. Esta oposición, que ha hecho esfuerzos de unificación y, al mismo tiempo, de separación de los actores anti democráticos del pasado, incluye a sectores medios profesionales que podrían contribuir tanto con la elevación de la calidad política de la actual democracia como con la mejora de una gestión pública postrada e ineficiente. Pero el pluralismo no es un valor para el presidente y la polarización le ha dado dividendos. Todavía no parece estar preparado para abandonarla.

En general, entonces, el discurso, pronunciado un mes después de la derrota, revela las conclusiones a las que ha llegado Chávez. Su objetivo es recuperarse en 2008 mediante un manejo más eficiente de la gestión pública, pero sin alterar su propuesta de socialismo. Ilustrativo de esto fue su promesa de convocar, si la oposición no lo hace, a un referendo revocatorio en su contra en 2010, con solo dos preguntas: “1) ¿Está usted de acuerdo con que Hugo Chávez siga siendo presidente de Venezuela? 2) ¿Está usted de acuerdo en hacer una pequeña enmienda en la Constitución para permitir la reelección indefinida? (con carácter vinculante)” [3]

Algunas Acciones

Las ideas formuladas por Chávez tras su derrota en el referendo constitucional permiten comprender algunas de sus más recientes actuaciones. En política exterior, por ejemplo, explican la continuación de sus relaciones conflictivas con Estados Unidos y Colombia. Durante la presentación de su informe anual a la Asamblea Nacional, el presidente solicitó públicamente al gobierno de Alvaro Uribe que le otorgue a las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) y al Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) status beligerante, lo que provocó en los días siguientes fuertes tensiones con el hermano país.

Esta solicitud tuvo el efecto de anular el positivo impacto internacional que había obtenido Chávez un día antes, cuando, por primera vez en años, las FARC aceptaron liberar a un grupo de personas secuestradas. La torpeza de Chávez fue tal que el pedido formulado ante la Asamblea Nacional contribuyó a un salto de la popularidad de Uribe en Colombia en las semanas siguientes. La solicitud no recibió el respaldo de ningún país latinoamericano, ni siquiera de Cuba. Como se recordará, en marzo, luego de que el ejército colombiano atacara un campamento de las FARC en territorio ecuatoriano, Chávez formuló una serie de expresiones que inicialmente fueron interpretadas como una posición favorable a esta guerrilla. Tras conversaciones con otros gobiernos latinoamericanos, el presidente bajó el tono y el protagonismo, y permitió que instancias como el Grupo de Río y la OEA se anotaran una victoria sobre las fuerzas que en la región buscan torpedear la integración latinoamericana y profundizar las tendencias bélicas.

En cuanto al PSUV, las últimas decisiones indican sólo débiles rectificaciones para fortalecer una dinámica colectiva y democrática. El diputado Luis Tascón, considerado como un referente del ala extrema del bolivarianismo, fue expulsado primero del Bloque por el Cambio de la Asamblea y después del aún sin fundar PSUV. El motivo fue haber denunciado ante la Comisión de Contraloría de la Asamblea irregularidades en la gestión de David Cabello en el Ministerio de Infraestructura. Cabello, junto a otros familiares, forma parte del entorno más cercano a Chávez y es considerado por las corrientes de izquierda dentro del bolivarianismo como cabeza de la “derecha endógena”. La presidenta de la Asamblea, Cilia Flores, criticó el hecho de que Tascón hubiera realizado sus denuncias en espacios públicos y ante los medios de comunicación.

Al mismo tiempo que se intentaban acallar las denuncias de Tascón, el Congreso Fundacional del PSUV, reunido en Caracas en febrero, aprobó un mecanismo basado en un procedimiento electoral de segundo grado para elegir a la dirección nacional del partido. Se introdujo adicionalmente otro eslabón en donde el dedo presidencial redujo la lista de candidatos significativamente antes de la elección de segundo grado. Aún así, la elección de una Dirección Nacional del PSUV proporciona al bolivarianismo una conducción colectiva relativamente legitimada desde abajo por la militancia partidaria.

Palabras Finales

Las elecciones regionales y locales de noviembre de 2008 serán importantes para medir si la estrategia del presidente y sus aliados es certera, si alcanza para recuperar su caudal electoral o si, por el contrario, marcará la continuación del declive de sus fuerzas. Mientras tanto, el gobierno redobla sus esfuerzos para lograr el abastecimiento alimenticio, sobre todo de productos básicos como leche, pan y arroz, ausentes en los últimos meses de los anaqueles de los comercios por una combinación de factores entre los cuales se encuentran la falta de planificación y la ineficiencia e insuficiencia de las políticas de desarrollo agropecuario. Venezuela sigue importando cerca de 70% de lo que necesita para comer o vestirse. Al mismo tiempo, las encuestas en los años recientes indican un aumento del consumo de los sectores populares gracias a una más efectiva distribución de los ingresos derivados de la exportación de petróleo a través de las misiones y otras políticas públicas. Sin embargo, hoy como ayer, esto es sólo sostenible por la renta petrolera, la más alta per cápita que haya recibido Venezuela en toda su historia[4].

En este sentido, la revolución bolivariana revive una vez más al Estado mágico que a lo largo de buena parte del siglo XX ilusionó con una modernización que las elites sólo supieron sostener con el excedente que la industria petrolera extrae del mercado internacional de hidrocarburos, sin ninguna contraparte nacional [5]. Ahora financia un vago “socialismo”. Cuando esa renta disminuye por algún motivo, o no crece lo suficiente, se vuelve a la situación real: un país con recursos pero sin capacidad de crear riqueza. Así se estrellan las fantasías. Para concluir, un gráfico, que ilustra cómo, en términos estructurales, casi diez años de bolivarianismo no han podido conjurar una estructura económica que repite los mismos vicios del pasado: desde mediados de los 50, la producción y el consumo no guardan ninguna relación entre sí. La brecha entre ambas es satisfecha por la renta petrolera.

[1] El Nacional, 6-01-2001

[2] Los extractos del discurso presidencial fueron publicados en el portal www.aporrea.org el 18-01-2008 y de los periódicos El Nacional y Últimas Noticias.

[3] Últimas Noticias, 13-01-08

[4] Baptista, Asdrúbal (2007): Bases cuantitativas de la economía venezolana 1830-2001, Caracas, Fundación Empresas Polar.

[5] Coronil, Fernando (1997): The Magical State, Chicago, Chicago University Press.

Fall 2008, Volume VIII, Number 1

Margarita López Maya is a historian. She holds a doctorate in social science and is a research professor at the Center for Economic Development at the Universidad Central de Venezuela. She is author of Del viernes negro al referendo revocatorio (Alfadil, 2005, Caracas) and Lucha popular, democracia, neoliberalismo: protesta popular en América Latina en los años de ajuste (Nueva Sociedad, 1999, Caracas), among other books.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Venezuela

Long, long ago before I ever saw the skyscrapers of Caracas, long before I ever fished for cachama in Barinas with Pedro and Aída, long before I ever dreamed of ReVista, let alone an issue on Venezuela, I heard a song.

Elections and Political Power: Challenges for the Opposition

English + Español

Next month’s elections will be an important benchmark in Venezuelan politics. On November 23, voters will go to the polls to elect 22 state governors and 355 mayors in as many municipalities, as well as choose the mayor of Caracas. The elections are taking place in a political environment influenced by the abrupt proclamation of 26 laws on July 31, the last day of President Chávez’s 18-month powers to issue emergency decrees …

A Review of Tramas del mercado: imaginación económica, cultura pública y literatura en el Chile de fines del siglo veinte

Luis Cárcamo-Huechante’s new book provides us with a convincing counter-narrative, at once nuanced and succinct, to three mainstream narratives of the neoliberal free market in Chile: those of monetarist economics, promotional politics, and literary bestsellers. It covers the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-90) and the transition to democracy from its official inauguration in 1988, with the victory of the Yes vote for a return in two years’…