Bittersweet Symphony

Chocolate Hippo, 2017, chocolate, 24 karat gold leaf

I’ve worked with chocolate for the last four years, but ironically, I only started drinking hot chocolate for breakfast a couple of weeks ago. My morning chocolate comes from our family plantation in the region of Quindío, Colombia, the country where I was born. My father planted the cacao trees; my mother roasted and ground the beans. While I sip this dark and delicious re-discovered miracle, I remember how my personal story with chocolate began.

When I was ten, my family moved to the tiny island of Providence, a volcanic rock island lush with green mountains and turquoise waters lost somewhere in the Caribbean. Once the strategic fortress of Elizabethan pirates, including Sir Francis Drake, it was where I spent a very romantic childhood with no electricity but enough Jules Verne’s and Emilio Salgari novels to enlighten the imagination of an adventurous spirit. That’s where the golden bug of the mirage of treasures first stung me. I would venture into every corner of the craggy mountains to explore alleys, creeks and caves, in search of any possible clue to a hidden treasure. I inquired with the older folks who knew the most about piracy, sunken ships and probable hiding spots. I snorkeled every shore, believe me, I tried every possible path. It never crossed my mind what would happen with the treasure once I found it. What mattered was finding the bloody thing in the first place.

During the next few years, I conceded to less lofty goals: I would settle for ordinary coins. Returning from a long snorkeling morning, opportunity presented itself at our seafront beach. Bounty on the sand set me off making seashell necklaces, which I sold at the local airport. I remember the magical experience of getting those coins in my hands. What today would be nothing but small change, felt like alchemy then. But challenges came quickly: seashells became scarce. The variety of tiny conchs I needed for the necklaces were in short supply during the dead calm of May.

Detail of chocolate soccer ball and butterfly. Photo by Jessica Regler

While waiting for the waves to bring in new gems, summer arrived and my mainland cousins flew in to spend a few months with us. It struck me to see how much they liked candy. More precisely, chocolate. This made for opportunity: I took my savings, went to Town (the place were you would go and buy groceries), and bought forbidden treasures to resell to my visiting relatives: Milky Ways, Snickers and Zero bars. You see, mainland Colombia had a closed economy, but the unhindered “piracy” of the Island allowed a trade in these precious delicacies.

Business took off quickly and sales soared. I guess you could say that chocolate gave me my first experience as an entrepreneur with a small enterprise. I had to run the entire business: buying, selling, marketing, managing inventories, dealing with occasional theft, and last but not least, resisting the temptation to eat up my own merchandise. Though business went well, it didn’t last long. Once the summer ended, with cousins and seashells nowhere to be found, I went back to daydreaming of treasures and pirates.

Some fifteen years later, at the beginning of my artistic career, I was drawn to a different sort of quest, not about finding or selling things of value, but about the notion of value itself. What made a work of art valuable? What made its price reach the levels hawked at auctions? Who were the folks running the game and why did they do it? What place did I have in this game? While these questions were spinning, parallel to my experiments with forms of painting, I set off into numerous entrepreneurial projects including cattle raising, restaurants and a boutique hotel.

As an artist, I spent nearly 10 years experimenting, centered mainly on the aesthetics, composition and structures of form and color until I had a major breakthrough. I replaced acrylics and canvas for paper money and stainless steel as the founding elements of construction. I figured that I could use banknotes, composing in the grid, while taking advantage of the inherent value that was already in the money. This turning point freed me from the tangle of values that had trapped me in the narrow rules in the art world and particularly the art market.

A new exploration began; I first ventured into the contents of the bills themselves. The aesthetics, narratives, symbols, heroes and ever-present commodities particular to every nation, all unveiled a multiplicity of human traditions and behaviors. It was a fascinating window into historical events, as well as a testimony of cultural identity, sense of pride, and promises of a better future. In the natural progression of this interaction with money, I exhausted the possibilities to the point of shredding the paper money and making new paper out of it, intentionally erasing its exchange value.

Tally sticks harvest. Photo by Santiago Montoya

Tally sticks harvest. Photo by Santiago Montoya

Tally sticks harvest. Photo by Santiago Montoya

Tally sticks knot. Photo by Santiago Montoya

Tally sticks, 2017. Photo by Juan Manuel Garcia

It has been about ten years since I first fell under the spell of money, and now I find myself dealing with the very things that it stands for: commodities. In the process of discovering the historical imbalances in commodity consumption between center and periphery, I began to explore the uses of various materials. One of my first works in this line was a wooden scaffolding structure called The Tally Sticks, which is a metaphor for the interconnectedness of the financial system, so fragilely tied together by promises that no eye (or sum of algorithms) can entirely comprehend it. To prepare this piece I ventured into a natural reserve called ‘El Cerro de Armas’ in Santander, Colombia, where my family protects over 12,000 acres of pristine jungle. With the help of local arrieros we harvested a hardwood balsamo tree that had died of natural causes. After cutting it into blocks and transporting it down from the mountains, it was cut into thin and very long sticks, crated and shipped to London were they were assembled and exhibited as part of an exhibition titled Improbable Landscapes. The process itself felt like drafting a sketch for a future banknote.

Following this unique experience, a new bug stung me. I became a sort of trader, interested in the origins of commodities, all the way back to the “discovery” of America. I was first captivated by the fascinating story of the Potosí mine, and how it became the source of silver coins that would become the first worldwide-circulating currency. Quina, and the discovery of quinine in the days of conquest followed. I like to think of the plant as the tree of fevers, not because it would cure them, but because it opened America’s pores to contract other fevers like the gold fever and many other extractive rushes to richness. Emeralds were an obligatory subject, of course, coal, sugar and coca. And then there are the seeds of the money tree: cacao. It holds great qualities: it is edible and smells delicious; one can cover it in gold or silver leaf to enhance its appearance (and still eat it). Eventually, it can be made into art, giving it a fourth dimension of value that holds great potential and a rarity too: it will gain an exchange value while keeping its use value. Just don´t let it melt!

Around the year 2016, having caught the chocolate fever, I began to work with my curator José Falconi on the project Missteps and Other Paths, which was exhibited at Espacio El Dorado in Bogotá a year later. This show had a unifying subject, which was the impossibility of Colombia to become a modern nation, despite all of its apparent riches. Among those riches which pass as potential game changers, cacao has become the latest trend of fortune and promise that is familiar since the Conquerors’ quest for El Dorado.

Missteps and Other Paths, 2017. Photo by Juan Manuel Garcia

Detail of Missteps and Other Paths. Photo by Juan Manuel Garcia

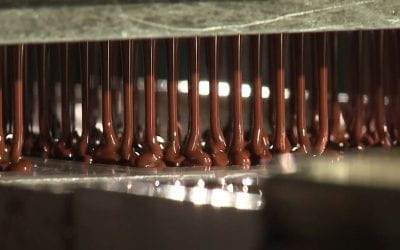

For this exhibition I made more than 12 different chocolate pieces, ranging from soccer balls to hippos (with allusions to Pablo Escobar’s famous zoo), all playing a role in the magical realism that is the history of Colombia. They were made from cacao harvested at our farm, processed into dark chocolate, and then covered in gold leaf. During the exhibition, in the three-story building, the narrative of this immersive experience included cacao beans that covered the ground floor with a Tally Sticks maze. A chapel-like installation followed in the second floor. Here, golden letters printed on reprocessed dollar bills tallied the failed promises made since the inception of the republic. At the end of the journey, a chocolaterie called “The Original’s Inn” awaited on the third floor. Visitors wrote personal promises on banknote sized scripts of paper that were then exchanged for a divine beverage: in a small cup of hot milk, a shamanic flight figure covered in gold, melted to reenact an El Dorado myth of the cacique bathing in the Guatavita lake. The second edition of this chocolate shop was set to take place at the Somerville Museum in Somerville, Massachusetts, just outside of Cambridge, this coming winter, but the coronavirus pushed the opening until the end of 2021. Planning for a show that involves communal sharing in the current state of the world has become a utopic mirage.

As much as with the Somerville Museum exhibit, we are following the day-to-day new normal on another previously scheduled exhibit at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS). Entitled Wheel of Fortune, this show includes chocolate engravings, but does not focus on it. Following an invitation made by Arts@DRCLAS (now Art, Film & Culture) to present in its second-floor exhibition space in spring 2021, I put together a variety of works created from 2012-2020, ranging from neon, to tapestries, videos and wooden sculptures, to chocolate engravings. A multidisciplinary forum, with the concept of value at its core, will convoke academics to debate and think about this topic, in conjunction with the exhibit.

The Original’s Inn. Photo by Jessica Regler

Preparation of hot chocolate during the exhibit at the Originals Inn. Photo by Juan Manuel Garcia

This type of thinking of value, going back to my long-ago search for seashells, has informed my work, whether on chocolate or paper money. Throughout these years, I have witnessed, studied and experienced many transformations. The madness that was initiated by the quest for El Dorado has by now become a recurring vertigo between stories of bravery and human greed. The cyclical rushes of mirages, driven by continuing ambition, haven´t receded. Cacao was transformed from what the Mayas considered to be the drink of the gods to become a demonic beverage prosecuted by the inquisition. I have learned, as a “chocolatier,” that in its solid state chocolate is an excellent and malleable material; and when it is covered in gold leaf, it becomes a treasure-like object. This should be a reminder of the trap that treasures inevitably set: if you hold on to them long enough, they start to melt, lose their value and inevitably slip through your fingers.

We may find ourselves hesitant many times in life deciding what is what; but one thing is certain from my artist’s experience of pursuing treasure. Value is an illusion like dark chocolate: bittersweet.

Sinfonía agridulce

Por Santiago Montoya

Hipopotamo de chocolate, 2017, chocolate y pan de oro de 24 quilates. Foto por Juan Manuel Garcia

A pesar de estar trabajando con chocolate durante los últimos cuatro años, irónicamente solo hasta hace unas pocas semanas comencé a tomar chocolate caliente al desayuno. El chocolate viene de nuestra plantación familiar en la región del Quindío en Colombia, mi país de origen. Mi padre sembró los árboles de cacao; mi madre tostó y molió los granos. Mientras sorbo este oscuro y delicioso milagro redescubierto, empiezo a recordar como comenzó mi historia personal con el chocolate.

Cuando tenía diez años de edad, mi familia se mudó a la Isla de Providencia, una roca volcánica cubierta de verdes montañas y mares azul turquesa perdida en algún lugar del Caribe. Alguna vez fortín de piratas, incluido el mismísimo Sir Francis Drake, fue donde viví una romantica niñez sin electricidad pero suficientes novelas de Julio Verne y Emilio Salgari para iluminar la imaginación de un espíritu aventurero. Fue allí donde el cucarrón dorado del espejismo de tesoros me picó por vez primera. Yo me aventuraba en cada rincón de las peñascosas montañas para explorar acantilados, quebradas y cuevas, en búsqueda de cualquier posible clave para encontrar el tesoro escondido. Indagaba con los viejos que más sabían sobre piratería, barcos hundidos y probables escondites. Caretié en cada orilla, créanme, intenté cada camino posible. Nunca se me cruzó por la mente qué pasaría con el tesoro una vez lo encontrara. Lo que importaba era encontrar la maldita cosa en antes que nada.

Durante los siguientes años, me conformé con metas menos ambiciosas: bastarían monedas ordinarias. Al regreso de una larga mañana careteando, se presentó una oportunidad en la orilla de nuestra playa. Un tesoro en la arena me puso a hilar collares de caracoles, los cuales empecé a vender en el aeropuerto local. Recuerdo la mágica experiencia de recibir esas monedas en mis manos. Lo que hoy no sería más que cambio menudo, se sintió como alquímia en aquel entonces. Pero los retos no demoraron en presentarse: los caracoles escasearon. La variedad de diminutas conchas que requería estaban en retirada durante la calma chicha de mayo.

Mientras esperaba que las olas trajeran consigo nuevas gemas, llegó el verano y mis primos del interior volaron a la isla para pasar unos meses con nosotros. Me impresionó ver cuánto les gustaban los dulces. Más precisamente, los chocolates. Lo cual se convirtió en una oportunidad: tomé mis ahorros, fuí al Pueblo (el lugar donde uno iba a hacer el mercado), y compré tesoros prohibidos para revender a mis parientes: barras de chocolate marca Milky Way, Snickers, y Zero. En aquel entonces la economía del interior de Colombia tenía una economía cerrada, pero la “piratería” sin obstáculos de la isla permitía el comercio de estas preciosas delicias.

Detalle de pelota de fútbol de chocolate y mariposa. Foto por Jessica Regler

El negocio despegó rápidamente y las ventas se dispararon. Supongo que se podría decir que el chocolate me dio mi primera experiencia como emprendedor con una pequeña empresa. Yo manejaba la totalidad de la operación: comprar, vender, mercadear, manejar inventarios, lidiar con los ocasionales robos, y por último, resistir la tentación de comer mi propia mercancía. A pesar de que el negocio funcionó bien, no duró mucho. Cuando llegó el fin del verano, sin primos ni conchas por ninguna parte regresé a mis ensueños de tesoros y piratas.

Unos quince años después, al principio de mi carrera artística, me dejé llevar por otra búsqueda, no relacionada con encontrar y vender cosas de valor, sino precisamente con la noción de valor en sí misma. ¿Qué hacía a una obra de arte valiosa? ¿Qué hacía que su precio lograra los niveles pregonados durante las subastas? ¿Quiénes eran los fulanos a mando de este juego y con qué fin lo hacían? ¿Qué lugar ocupaba yo en este juego? Mientras estas preguntas me embriagaban, en paralelo a mis experimentos sobre técnicas de pintura, me ocupé de numerosos emprendimientos incluyendo ganadería, restaurantes y un hotel boutique.

Como artista, estuve cerca de 10 años experimentando, centrado principalmente en la estética, composición y las estructuras de forma y color hasta que tuve una ruptura transcendental. Reemplacé los acrílicos y el lienzo por dinero y acero inoxidable como los elementos fundamentales de construcción. Supuse que podría utilizar billetes para componer en la retícula mientras aprovechaba el valor inherente que ya llevaba consigo el dinero. Este giro me liberó de la maraña de valores que me tenía atrapado en las estrechas reglas del mundo del arte y particularmente de su mercado.

Una nueva exploración comenzó; primero me aventuré en el contenido de los billetes. La estética, narrativa, símbolos, héroes y las siempre presentes mercancías, particulares a cada nación, todas develaron la multiplicidad de tradiciones humanas y su comportamiento. Fue una ventana fascinante al interior de eventos históricos, así como un testimonio de la identidad cultural, sentido de orgullo, y promesas de un futuro mejor. En la progresión natural de esta interacción con el dinero, agoté las posibilidades hasta el punto de triturar el papel moneda para hacer un nuevo papel del mismo, intencionalmente borrando su valor de intercambio.

Tally sticks harvest. Photo by Santiago Montoya

Tally sticks harvest. Photo by Santiago Montoya

Tally sticks harvest. Photo by Santiago Montoya

Tally sticks knot. Photo by Santiago Montoya

Tally sticks, 2017. Photo by Juan Manuel Garcia

Han pasado cerca de diez años desde que caí bajo el hechizo del dinero, y me encuentro actualmente lidiando con las cosas que representa: mercancías. En el proceso de descubrir los desbalances históricos de consumo entre centro y periferia, empecé a explorar el uso de varios materiales. Uno de mis primeros trabajos en esta línea fue un andamio de madera titulado The Tally Sticks (Los Palos Contables), el cual es una metáfora de la interconexión del sistema financiero, tan frágilmente atado por promesas que nigún ojo (o suma de algoritmos) puede comprenderlo en su totalidad. Para la preparación de esta pieza me aventuré en la reserva natural de El Cerro de Armas en Santander, Colombia, donde mi familia protege cerca de 12,000 acres de selva virgen. Con la ayuda de arrieros locales aprovechamos un árbol de balsamo que había muerto por causas naturales. Después de cortarlo en bloques y transportarlo montaña abajo, fue cortado en delgados y largos palitos, enguacalado y enviado a Londres donde fue presentado como parte de la exhibición titulada Paisajes Improbables. El proceso en sí se sintió como un boceto para un futuro billete.

Después de esta maravillosa experiencia me picó otro bicho. Me convertí en una especie de mercader, interesado en los orígenes de los commodities, viajando en el tiempo hasta el “descubrimiento” de América. En un principio me cautivó la fascinante historia de la mina de Potosí, y cómo la misma se llegó a ser la fuente de las monedas de plata que se convertirían en la primera moneda de circulación global. La quina, y el consiguiente descubrimiento de la quinina en los días de la conquista le siguieron. Me gusta pensar en esta planta como el árbol de la fiebre, no porque fuese su cura, sino porque abrió los poros de América para que contrajiese otra fiebres como la del oro y muchos otros afanes extractivos por la riqueza. Las esmeraldas se convirtieron en otro tema obligatorio, así como el carbón, el azúcar y la coca. Y por último están las monedas del árbol del dinero: el cacao. Este contiene grandes cualidades: es comestible y huele delicioso; se puede recubrir en hojilla de oro o plata para embellecer su apariencia (y aun así comerlo). Eventualmente, se puede convertir en arte también, dándole una cuarta dimensión de valor que encierra un gran potencial y gran rareza: ganará un valor de cambio mientras conserva su valor de uso. Simplemente no lo dejen derretir!

Malpaso y otros senderos, 2017. Foto por Juan Manuel Garcia

Detalle de malpaso y otros senderos. Foto por Juan Manuel Garcia

Alrededor del año 2016, habiéndome contagiado de la fiebre del chocolate, empecé a trabajar con mi curador, José Falconi, en el proyecto Malpaso y otros senderos, el cual fue exhibido en el Espacio El Dorado en Bogotá un año después. Este show tuvo un tema unificador que fue la imposibilidad de Colombia de convertirse en una nación moderna, a pesar de sus aparentes riquezas. Entre estas riquezas, que posan como potenciales transformadoras, el cacao se ha convertido en la última tendencia de fortuna y promesas que nos es familiar desde la búsqueda de El Dorado por los conquistadores.

Para esta exhibición hice más de 12 piezas diferentes en chocolate, desde balones de fútbol hasta hipopótamos (aludiendo al famoso zoológico de Escobar), todos jugando un rol en la realidad mágica que es la historia de Colombia. Las mismas fueron esculpidas con cacao cosechado en nuestra finca, el cual fue procesado para hacer chocolate amargo, y entonces se recubrieron en hojilla de oro. Durante la exhibición, en el edificio de tres pisos, la narrativa de esta experiencia inmersiva incluía semillas de cacao cubriendo toda la superficie del primer nivel, dentro del cual se erguía un laberinto de la obra Tally Sticks (Palos Contables). Acto seguido, en el segundo piso, se accedía a una instalación que semejaba una capilla. En ella, letras doradas impresas sobre pliegos de dólares reprocesados contabilizaban las promesas fallidas hechas desde el principio de la república. Al final del recorrido, la chocolatería “The Original’s Inn” (La posada de los originales) esperaba en el tercer piso. Los visitantes escribían promesas personales en piezas de papel del tamaño de billetes, los cuales eran intercambiados por la bebida divina: en una pequeña taza de chocolate caliente, una figura recubierta en oro representando el vuelo chamánico, se derretía para recrear el mito del cacique sumergiéndose en la laguna de Guatavita. La segunda edición de esta tienda de chocolate estaba programada para tener lugar en el Museo de Somerville, en la ciudad de Somerville, Massachusetts, cerca de Cambridge, durante el próximo invierno, pero el coronavirus retrazó su inauguración hasta fianles del 2021. La planeación de una muestra de esta naturaleza en el actual estado del mundo se ha convertido en un espejismo utópico.

The Original’s Inn. Photo by Jessica Regler

Preparación de chocolate caliente durante la exhibición en el Original’s Inn. Foto por Juan Manuel Garcia

Así como lo hemos hecho con la exhibición del Museo de Somerville, estamos siguiendo los lineamientos día a día de la nueva normalidad para una exhibición ya planeada en el David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS). Titulada La rueda de la fortuna, esta exhibición incluye grabados de chocolate, pero no se enfoca en este material. Aprovechando la invitación hecha por Arts@DRCLAS (ahora Arte, Cine y Cultura) para presentar en el segundo piso una exhibición en la primavera del 2021, he reunido una variedad de trabajos creados entre los años 2012-2020, variando desde un neon, tapices, videos y esculturas de madera, hasta grabados de chocolate. Un foro interdisciplinario, cuyo fundamento es el concepto de valor, convocará académicos con el fin de debatir y pensar acerca de este tema, en conjunto con la exhibición.

Esta manera de entender el valor, yendo hasta los días en que buscaba caracoles, ha enriquecido mi trabajo, ya sea con chocolate o papel moneda. A través de estos años he presenciado, estudiado y experimentado muchas transformaciones. La locura que desató le búsqueda de El Dorado se ha convertido hasta el día de hoy en un recurrente vértigo entre historias de valentía y codicia humana. El cíclico afán de espejismos, impulsado por la ambición contínua, no retrocede. El cacao se transformó de lo que los Mayas consideraban era la bebida de los dioses para convertirse en una bebida demoníaca perseguida por la inquisición. He aprendido, como “chocolatero”, que en su estado sólido el chocolate es un material excelente y maleable; y cuando se cubre con hojilla de oro se convierte en un cuasi-tesoro. Esto debería ser un recordatorio de la trampa que infalíblemente suponen los tesoros: si te aferras a ellos por demasiado tiempo se derriten, pierden su valor, e inevitáblemente se escurren por entre tus dedos.

Podremos encontrarnos muchas veces en la vidad dudando acerca de qué es qué; pero estoy seguro de algo que he aprendido a través de mi práctica artística persiguiendo tesoros. El valor es una ilusión como el chocolate amargo: agridulce.

Fall 2020, Volume XX, Number 1

Santiago Montoya is a Colombian artist residing in Miami since 2012. His work is centered on the notion of value, and how its meaning has evolved throughout history. Following an extensive exploration using paper money as his main medium, he has more recently experimented with materials such as gold, emeralds, chocolate, quinine, rubber and coal.

Santiago Montoya es artista colombiano residente en la ciudad de Miami desde el año 2012. Su trabajo se centra en la noción del valor, y como su significado a evolucionado a lo largo de la historia. Siguiendo una extensiva exploración utilizando papel moneda como su principal medio de expresión, se ha concentrado más recientemente en experimentar con materiales como oro, esmeraldas, chocolate, quina, caucho y carbón.

Related Articles

Between America and Europe

On Tuesday, September 9, 1645, at 12 noon, the cocoa trader Antonio Méndez Chillón was arrested at his home in Veracruz (New Spain) by the Inquisition commissioner and charged with Jewish heresy. This episode, which was far from being isolated, helps shed…

Divine Decadence or Business Turnaround?

English + Español

Back in 2006, we became intrigued about a chocolate company in Venezuela. Rohit had done quite a bit of work on companies that were integrating country of origin into their product branding. He called it the Provenance Paradox. As Director of HBS’s Latin America…

Small (Labor) Truths

In 2005, a company named Taza debuted a new way to do chocolate. The disc-shaped bars produced in their Somerville, Massachusetts factory were minimally processed from from ethically-sourced cacao and contained only ingredients that might…