Blending English and Traditional Cultures in Colombia

A Case from Bogotá

The first time I encountered ancestral Colombian Amazon cultures, I was struck by how people from different ethnic groups used Spanish as their common language, but used their traditional language in family gatherings or in work within their own communities. I was impressed by how even in missionary chuches, texts from Western religions were mixed with a syncretism of cosmovisions. Together, they formed a communications channel through the supra-cultural values giving new meaning to what it means to be indigenous in Colombia from the perspective of the 1991 Constitution that declared the country to be pluri-ethnic and multicultural.

However, when I set out to do ethnographic research, I found a different reality. The community was losing the use of traditional languages. I went to the local school and found that in spite of having textbooks in the indigenous language of the predominant ethnic group, these texts were not used to teach language in high school, where English classes prevailed nor in the natural sciences (other than those that teach so-called indigenous categories).

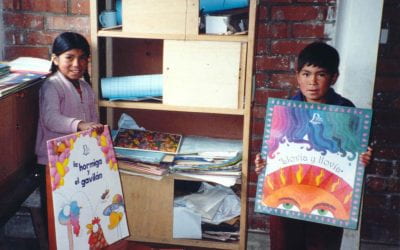

Drawing by Raices Nativas Amazonicas, a project in the Colombian Amazon to imbue educational activities with cultural meaning.

I decided to create a bridge between the wise elders of the community and the school, creating a text about local medicinal plants, written in both the indigenous language and in Spanish. The textbook allowed the elders a role in the school, participating with teachers in a laboratory about the importance of traditional language, the collection of plants and the preparation of natural remedies.

This experience left me somewhat frustrated about the way Colombia allows economic pressures to homogenize the pluri-ethnic and multicultural richness of the nation, leading one village in the Amazon, for example, to experience the loss of its traditional language and culture by prioritizing a foreign language like English (schools teach one language and thus are forced to choose what will fulfil the language requirement).

Colombia lacks a public policy to protect indigenous languages, as Gary Eberhard and C. Fennig point out in Ethnologue: Languages of the World (2019) and according to a 2010 UNESCO report. Twenty-one traditional languages have disappeared in Colombia, recently including carabayo and macaguaje in the Amazons, opón-carare in Santander, pijao in Tolima and kankuamo on the Atlantic Coast, which illustrate the degree of challenge to intercultural competence, which revalues the local through tools that motivate students to make visible and live their cultural richness through a foreign language.

This situation prompted me to research the bilingual intercultural conflict and the existence of programs geared toward the teaching of traditional cultures in urban contexts. Thus, the idea was conceived and later designed to mix English teaching and the Tikuna myths as an intercultural focus, representing a tool to mitigate the need to make a choice between English and indigenous culture in a group of students in a Bogotá school.

This new experience was seen as a way of combatting the gradual and systematic extinction of language and culture caused by the displacement of different communities to the city, as recounted in the National Center of Historic Memory’s 2014 report, Guerrilla y población civil trayectoria de las FARC 1949-2013. This guided learning awakens what we might call micro-ethics, micro-politics and micro-revolutions, through the knowledge of people from other cultures as subjects whose qualities are discovered, rather than being received in a stereotypical fashion.

The results of this experience in an urban context provides evidence that the individual producer of a language is also a product of this language, and that the teaching of myths in the English language from a Colombian ethnic group like the Tikuna not only helps recognize the individual and collective identity of the students, but also provides a tool that permits a solution to this inercultural bilingual conflict through semiological acts in daily life.

In this way, multicultural education should provide a counterbalance to the assimilationist trend. Both emotionally and through the acquisition of knowledge, this multicultural approach helps in the construction, cohesion and communication of the cultural diversity of our societies. A great challenge is to change the arrogant positions that one culture can be considered superior to another, and to accept local cultural patterns as part of one’s identity.

A school that makes the transition from functional interculturality to a critical or ethical-political interculturality does so by combining ways of learning that make changes that one can call de-colonizing. The way to achieve this is through changes from the vantage of micro-ethicsand micro-politics that spawn micro-revolutions in behavior that are not only conditioned by the context of class without being recognized by the family for its handling of self-awareness and action, as well as responsibility and individuality.

The English-language teaching of the Tikuna myths not only is a solution for the tension between teaching English and the indigenous languages, but it also permits a Colombian ethnic minority to do away with the uniformity of globalization. Through both social and semantic processes, students elaborate scripts and exercises, new concepts through the daily situatiions of one of the local groups ad languages that do not usually take place in traditional learning models. In the words of J. Bruner in The Culture of Education (Cambridge: Harvard University Press), this leads to a restructuring, the biology of meaning through stories that give subjectivity to reality, through the micro-revolutions of behavior known as communicative intercultural competence or CCI, after its acronym in Spanish (as discussed by L.Sercu in “Teaching Foreign Languages in an Intercultural World,” in L. Sercu, E. Bandura, P. Castro, L. L. Davcheva, M. Méndez, & P. Ryan, Foreign Language Teachers and Intercultural Competence. An International Investigation.)

CCI integrates the teaching of languages with the development of socio-emotional and socio-linguistic abilities by promoting emotions that contribute to the collective construction of interdisciplinary framework that allows students to become aware of the indigenous regional realities of the Colombian Amazon region. They can begin to make sense of the pluriethnic and multicultural context promulgated in the 1991 Political Constitution, through one of the 65 Colombian indigenous languages (Tikuna) and two of the 70 languages of the territory, through the teaching of a foreign language that is considered the second official language of the territory (English) as a strategy “to guarantee inclusive, equitable and quality education and to promote opportunities for life-long learning for all (goal four of the United Nations sustainable development goals, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/education/).

Thus, English classes from the stance of CCI provide a space for the teaching of foreign culture, and also an intercultural environment for the construction of a society that values, reflects on, recuperates and revitalizes the pluri-ethnic and multicultural.

Thus any class, even those such as English learning that initially seem to be denying the rich local multilingual culture, is an intercultural scenario by definition, where one encounters the diversity to construct and reconstruct societies through socio-linguistic competence. These classes have the potential of responding to the necessities and demands of all without causing damage to anyone.

Fall/Winter 2019-2020, Volume XIX, Number 2

Ronald Fernando Quintana Arias is a Colciencias-approved peer reviewer with a Master’s in Sustainable Development and Environmental Management who is working on his doctorate in Social Studies. He has taught, led projects and published widely on social, economic and environmental themes, focused on urban, rural, indigenous and Afro-descendant communities.

Related Articles

Ghosts of Sheridan Circle

Targeted killing of political enemies—assassinations—is thankfully rare in the United States. The most famous such assassination occurred in Washington, DC. And it was committed by a close ally of the United States. In September 1976, Chile’s Pinochet dictatorship…

Bilingualism: Editor’s Letter

It was snowing heavily in New York. It didn’t matter much to me. I was in sunny Santo Domingo with my New York Dominican neighbors on the Christmas break from school. I learned Spanish from them and also at the local bodega, where the shop owner insisted I ask…

Two Wixaritari Communities

English + Español

I first arrived in the wixárika (huichol) zone north of Jalisco, Mexico, in 1998. The communities didn’t have electricity then, and it was really hard to get there because the roads were simply…