Bolivia’s Amazon

Power and Politics Stoking the Flame

The fires that raged across the Amazon basin last fall hit Bolivia particularly hard. From September to November, the fires swept through more than 3,000 square miles—twice the area of Rhode Island—, much of it in the pristine dry forests of the Chiquitanía area. Yearly burning by farmers clearing land is nothing new in the region. Yet 2019 was particularly intense. Fires spreading worldwide sparked newfound concerns about drought, global warming and the fate of the planet.

The fires in Bolivia became a political battleground that went beyond more familiar environmental debates. In the heated election season, Bolivia’s then president, the left-leaning Indigenous leader Evo Morales, blamed the big agro-business of the Bolivian east. His detractors blamed him. The opposition was already hoping to topple him in the October elections because they saw his bid for an unprecedented fourth term as unconstitutional. Although the environmental bonafides of the Bolivian right are a bit doubtful, the fires became a useful means for all those opposed to Evo to declare themselves green and attack his relative popularity, both nationally and internationally.

Conspiracy theories about the disastrous fires abound. For those on the left, it is not hard to believe that a concerted effort by landowners—perhaps even tied to President Jair Bolsonaro in neighboring Brazil—wanted to use the fires to wage an all out assault on the land. In Brazil, Bolsonaro’s overt assault on Indigenous rights and his dismissal of environmentalists’ concerns find an echo in eastern Bolivia, where big agro-business interests have long been closely aligned with the Brazilian agrarian lobby, the ruralistas. (In fact, huge swathes of soy land in Bolivia are owned directly by Brazilian investors and farmers). By extension, it is not hard to imagine that following Bolsonaro, Bolivia’s right-wing would use the fires to advance its economic interests and hurt Evo Morales on the eve of elections.

Indeed, the right had generated a story of scandal just prior to the 2016 referendum that Evo lost in a bid to extend term limits. The scandal turned out to be largely fake news, yet his loss forced Evo to go to the courts to make a fourth run on the presidency. The interests at stake are immense. Cattle-ranching and large-scale farming of soy and sugar-cane, as well as timber and gold mining have long been the base of power for elites across Bolivia’s Amazonian lowlands. Landgrabs of state-owned land—and that of Indigenous peoples—have been the right’s most common method for expanding their economic and political base there. As such, starting fires for political gain is well within the scope of rationality for these elites. Whether intentional or not, the massive fires in 2019 did play to the interests of these landed elites, both for clearing land and for undermining the leader they hoped to topple.

Yet Evo Morales and the MAS bear some responsibility as well. By 2013, Morales’ allegedly leftist government, locked in mortal combat with the landed elite since 2006, made a pragmatic deténte with big agro-business. Natural gas prices had fallen and the government hoped to shore up the books by increasing agricultural production. This meant abandoning its progressive land reform plans and removing restrictions on the expansion of the agrarian frontier: in other words, deforestation. Activists critical of Evo Morales have pointed to legislative measures since then. In 2013 the government passed a general pardon for those who had carried out illegal deforestation between 1996 and 2011. In 2015, another law allowed deforestation by small landholders by reducing restrictions on legal burning (since smaller farmers generally do not have heavy machinery to clear land). The measure, according to critics, gave way to uncontrolled burning while larger landowners took advantage of the opening to do burning of their own.

In 2018 another law reversed Evo Morales’ longstanding opposition to biofuels (biodiesel from soy and ethanol from sugar). Confronting a fuel shortage and intense pressure from the soy and sugar industry, the government moved to promote plant-based fuel production and promised to buy ethanol. This incentivized more deforestation. Finally in 2019, the state passed measures that further encouraged agrarian expansion. One law sought to regulate controlled burning as a “productive activity” but made it easier to burn down trees. In August of 2019, a month before the uncontrolled fires erupted and just two months before the elections, a presidential decree authorized new deforestation in areas of Santa Cruz and Beni departments. The combined interest in expanding soy and sugar frontiers for biofuels and expanding cattle production for exports to China both implicated government policy in the fires. Even if he did not light the match, Evo’s policies certainly helped shape conditions for the inferno.

Yet Evo Morales is too much of an easy target for detractors, whether armchair environmentalists of the Global North or arch-conservative elites who dominate Bolivia’s agroindustrial east. We must think more deeply about the relations of political power and the pressures of capitalist markets that have threatened the Amazon in ways that go beyond Evo and the fires last year. With Evo no longer in the presidency and the country riven by inequalities, whichever new political forces emerge—and especially if they are on the right side of the political spectrum—the pressures on the Amazon will certainly intensify.

Spring/Summer 2020, Volume XIX, Number 3

Bolivia’s eastern lowlands, long a backwater—except for the times it was gripped by booms like rubber or wars for territory in the early 20th century—, experienced new pressures after the 1950s. The U.S. government helped Bolivia build new roads, encouraged the resettlement of poor Andean peasants (to diffuse revolutionary pressure) and financed cattle, farming, and oil across the lowlands. During the U.S.-backed Banzer dictatorship (1971-78), the old general handed out land right and left to cronies, laying the base for those who now hold power and establishing a relationship between state largesse and socio-environmental destruction.

This changed little with the return of democracy as deforestation and disposession of Indigenous and peasant communities continued. Along with wealthy Bolivian landowners, the culprits also included expanding Mennonite colonies, all involved in sugar, sorghum, wheat, and soy cultivation. (Mennonites, although often maintaining traditional lifestyles, operate huge farming operations across eastern Bolivia, often insulated from state laws and regulations.) To a lesser extent, the settler communities arriving from the Andes—known as colonos—were also establishing small-scale farming communities in the east, often deforesting and pushing lowland Indigenous peoples off the land as well.

With World Bank support in the 1990s, soy cultivation expanded in the Bolivian east, along with deforestation. In effect, the World Bank subsidized deforestation, a fact it has itself acknowledged. During the 1990s, Bolivia’s east also saw the expansion of Brazilian land ownership, as wealthier Brazilians moved in to snap up cheap land, by then increasingly scarce in their own country. By the same token, cattle, long used as a speculative hedge by Bolivia’s elites, has boomed with the growth of the urban consuming class in Bolivia and with growing exports, including the opening to China. In recent years soy and cattle have become kings.

Deeper in the hinterlands, other ills plague the forest. Along the great rivers of Bolivia’s Amazon, such as the Madre de Dios, small and large scale mining companies, some organized as cooperatives, are dredging for gold. Since the 1970s and 1980s artisanal miners have panned and sifted for gold. But with the free-market neoliberal turn of the 1990s, the path was opened for the expansion of private mining concessions across the country. These patterns changed little when Evo Morales came to office. Despite lofty rhetoric, the government did not nationalize mining operations or constrain their expansion, but actually consolidated existing operations that were both legal and illegal. In contrast to policies aimed at deepening state control in other sectors, the government allowed large- and small-scale mining, including informal and illegal mining to run free. The impacts of alluvial gold mining in the Amazon have been much studied and are well documented.. Alluvial mining involves dredging fragile river ecosystems and using and discharging toxic mercury into water systems. Mining attracts workers to remote regions, often introducing new threats to Indigenous or Amazonian communities, including violence if mining activities are resisted. Workers themselves invariably suffer poor working conditions. Larger operations, including some connected to Brazilian and Chinese investors, involve large dredging boats and machines.

In order to try to reduce contraband and capture some income, the Morales government established a very low rate on gold transactions, as low as 1.5%. Yet policing mining across a vast remote region is difficult. CEDIB, a Bolivian NGO, argues that the MAS government actually exacerbated it. In addition, organized mining cooperatives have frustrated attempts to formalize and control the industry and Evo’s government relied on their political support. Despite much talk of Mother Nature, Evo’s government hoped to capture taxes and establish political bases of support in the contested Amazonian regions rather than put a stop to mining (CEDIB 2017).

Other more familiar threats, including timber cutting and illicit drug manufacturing also create challenges for the region. The environmental question in Bolivia has been riven by tensions between ecological degradation and the push development through natural resource extraction. The question becomes if and how any government, left or right, can establish institutions to oversee more rational and sustainable forms of resource use or create economic alternatives for people and communities who look to extraction as a form of survival. This longstanding challenge is now further complicated by the shifting positions of left and right on the question of nature.

On the left, Evo Morales always spoke of Mother Earth (Pachamama) being pitted in a war to the death with capitalism. While such talk evoked hopeful cheers early in his presidency, the Morales government remained deeply committed to mining, big agriculture, and gas and oil, all of them more firmly in line with capital than with Mother Earth. When the Morales government moved to build a new highway through a protected natural and Indigenous area in 2011—the TIPNIS reserve—among the rather unexpected and vociferous defenders of nature who emerged were the urban middle classes, generally conservative and right-leaning. The TIPNIS struggle pretty much shed Evo of his environmentalist clothes.

In response, and curiously, many on the right now speak of defending nature. To my mind this is little more than a tactical (and even cynical) turn, given the right’s long history of disregard for both nature and Indigenous peoples’ rights. But Evo’s bungles in the jungles helped the anti-Evo urban middle classes discover a newfound love for nature – as a new means of attacking Evo. As the fires finally burned out the conflicts over the October 2019 elections erupted. The “environment” was one of many banners waved by the opposition. Among others, this became more visible with the organization “Standing Rivers” (Ríos de Pie). Ignoring the role of big business, these activists worked hard to blame the fires on Evo Morales, seeking to garner international sympathy for the forest and create antipathy for the Indigenous president. Evo’s supporters saw many of these supposed environmentalists as agents of the right-wing, and with some reason. The Standing Rivers group is led by a young Bolivian with funding ties to conservative human rights organizations and institutions involved with the so-called color revolutions, the U.S.-backed mobilizations that toppled leaders in eastern Europe. Yet the conscientious work of long-standing Bolivian NGOs also suggest that environmentalism is not just a right-wing tool. In addition, though Evo still had massive popular support, some rural and Indigenous people have turned away from Evo because of the impacts of development activities. At any rate, Evo’s eventual resignation in the face of military pressure has opened to door to the return of the right. It remains to be seen whether and how this urban right-leaning environmentalism represents something real, given that the right-wing government that replaced Morales has deep connections to the extractive industries. Among the most extreme factions of the opposition that helped oust Evo are the cattle-raising and soy-growing forces and interests that helped start the fires last fall. At this writing, the so-called “transition government” is deepening the ethanol incentives by promising to buy 160 million dollars worth of the fuel (at a loss) to add to the gasoline supply. Those who thought Morales had become an enemy of nature – and took some pleasure in castigating leftists who supported him – can now redirect their attention to the right.

In the Bolivian Amazon, the possibility for an alternative future lies in robust policies in defense of nature and of Indigenous rights, as well as a turn away from chemical-heavy forms of highly mechanized industry which produces few jobs, few returns for other economic sectors, and noxious social and ecological effects. A number of shifts might help both the Amazon and ecological systems more broadly. Certainly a turn away from fossil fuels is fundamental – and a rejection of biofuels as well – with transportation systems gradually going electric. Bolivia’s own lithium reserves might come into play in that regard. Similarly, the dismantling – or at least containment – of the ongoing monopolization of agricultural production by multinational firms like Bunge and Cargill, along with the highly chemicalized and mechanized production matrices they encourage, is necessary. Governments should support small-scale, organic, alternative, and ecologically sustainable agriculture rather than continue subsidizing big producers. Providing economic and technical assistance for smaller producers and ending policies aimed at expanding production through deforestation –are also necessary. Rethinking and restructuring national economies to create more labor intensive industries, and thus removing incentives for people to participate in illicit or ecologically destructive activities will also help. Soy, gold, and beef are not going to save Bolivia’s economy or provide a path to equitable development. But they will most certainly continue to degrade Bolivia’s Amazon.

Bret Gustafson teaches anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis. He is the author of Bolivia in the Age of Gas (Duke 2020) and New Languages of the State: Indigenous Resurgence and the Politics of Knowledge (Duke 2009). This article draws on sources from CEDIB (Bolivia); Fundación Tierra (Bolivia) and Bolivian press accounts.

Related Articles

Borderland Battles

When then-President Juan Manuel Santos signed a peace accord with one of the Western Hemisphere’s oldest guerrillas in 2016 (the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), optimism ran high that an end to decades-long violence in Colombia had been…

Exile Music

Novels about the Holocaust and Jewish survival span countries and languages and audiences of all ages. Such stories tend to be told against a European or United States background. Rarely does a novel involve European Jewish refugees who found sanctuary in Latin…

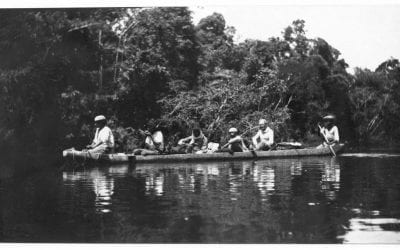

Fluvial Poetics in the Amazon

English + Español

We were in the hands of the river. I had been told that the boat for Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, would depart from Santarém at noon. Instead, we set sail at 2 pm. The arrival was even more difficult to determine. The guy who sold me the tickets assured me that…