Colombia’s Broken Body

El Colegio del Cuerpo: The College of the Body

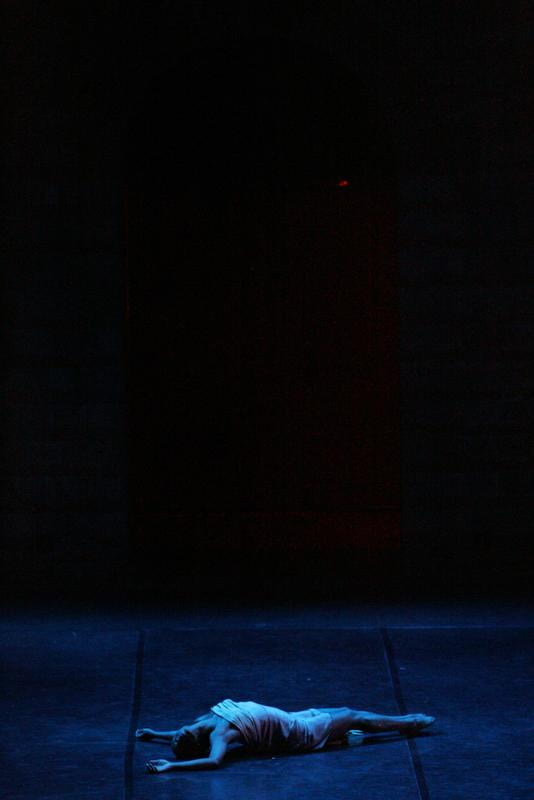

An ECDC dancer depicts the impact of violence in El Otro Apóstol, created by Marie france Delieuvin. Photo by Carlos Mario Lema

We Colombians are constantly asking ourselves what we can do for this torn and martyred country from the vantage point of our work activities.

Anguished, intimidated and powerless, we see how the language of weapons and death has become entrenched in our society. Every day, more and more Colombians become resigned to the idea that only total warfare, dragging us down to the abyss, will allow us to find a solution. But even more of us are convinced that we need to liberate another language to name and transform the reality before it is too late. Perhaps it is a matter of returning to the original truths of life, expressed in nature’s basic words, in the fresh and unpolluted eyes of the children, in the simple soul of things and the simplest beings.

This is why we work with dance—as dancers and as teachers.

I work in El Colegio del Cuerpo with children and youth from Cartagena’s poor neighborhoods. I try to offer them education and opportunities—which I didn’t have myself growing up—to discover from their earliest years their vocation and their talent. These young people have known firsthand what it is (is) to have a hard life, the entrenched injustices of the society, the ignorance of parents and the startling indifference of living creatures to the simple beauty of the universe. They have touched and been touched by violence. They were born into and grew up in the most devastating years of the conflict that afflicts us and don’t know any other reality except that of war. But, paradoxically, they are for the most part happy human beings and loved by their parents who give them, to the best of their possibilities, the best life that they can and know how to provide.

In El Colegio del Cuerpo, we try to create consciousness about the joy of living, the pleasure of discipline, the notion that the children are masters of a powerful and unique instrument that is their body, their being, with which they can play, create, enjoy, transform and be transformed. We teach them to marvel each and every day at what they are capable of doing and being so they can feel like gods or semi-gods—why not?—so that they can recognize the divinity within themselves and their fellow students, as well as the venerable character of their bodies, of their being and that of others.

Dance superstar Martha Graham, with whom I had the privilege to study in New York, once said, “It takes ten years to make a dancer!” With this in mind, I founded eCdC in 1997, together with the French dancer, choreographer and pedagogue Marie France Delieuvin. Following quite literally Graham’s educational precepts, we planned to graduate 13 dance-teaching professionals that very year as a result of an agreement with the Universidad de Antioquia, the Universidad Tecnológica de Bolívar and the Culture Ministry. El Colegio del Cuerpo (eCdC) is now a nonprofit organization for nontraditional and human development education.

We now work in two separate directions: education for dance to form dancers and education through dance so that youth begins to understand the body as a territory of peace. We have 46 youths who are on their way to becoming professional dancers. Many more are beginning to realize that participation in dance, in this realization of the body, leads to the prevention of violence and drug addiction and promotes citizenship, good nutrition, sexual and environmental education.

It is in the latter area—education through dance—that we just received a grant from the government of Japan through the World Bank to implement our methodology and philosophy in seven educational centers in the most depressed zones of Cartagena, better known in the outside world for its magical colonial center and sandy beaches. With this new program, 3,600 young Colombians will engage in learning through dance in PROYECTO MA*: Mi cuerpo, mi casa (My body, my home).

We have done this type of work for many years in poor Cartagena neighborhoods, including the shantytown known as Nelson Mandela, which shelters more than 50,000 refugees displaced from continuing civil violence in other parts of Colombia.

François Matarasso a Britain-based writer with a particular interest in the relationship between culture and democratic society, eloquently described our work in an article entitled “Human Bridges,” published in the journal Animated:

[Nelson Mandela] is not a place where most of us would expect contemporary dance, performed to a soundtrack of Jacques Brel or Buxtehude, to be meaningful: so much for our expectations…

The event at Nelson Mandela was part of the second ‘Festival de las Artes,’ created in Cartagena by two contemporary dancers, Alvaro Restrepo and Marie France Delieuvin, and their company CorpoPuente (body-bridge)….the inclusion of the edge place that is Nelson Mandela was central to CorpoPuente’s ethic of trying to create a role for art in healing a society riven by war, organised crime and poverty.

For two years Restrepo and Delieuvin have struggled against huge odds to develop a college of contemporary dance which not only gives young people routes to alternative futures but through its performances creates experiences of hope, anguish, pain and renewal which are the proper, unique business of art. Some of the young people involved may go on to become professional dancers; most will not, but their abilities, confidence and self-possession will have grown beyond measure. If nothing more, it is hoped that a new respect for their bodies acquired through dance may serve them in a society where drugs, often adulterated, are widespread.

As I said, though this work is among the best art I’ve seen—community-based or not—it would be meaningless to say that it is better than comparable work I’ve seen in Europe. The reason for focusing on it here is that the vibrancy, courage and quality of the dance work of CorpoPuente stands fairly alongside the deep political and social difficulties of Colombia. It is neither a solution to those problems (at least not on its own) nor an impertinence in the face of them. It is integral of the moral, creative and spiritual fabric of its society: that is its value. How much contemporary arts practice in the UK can truly claim as much?

There is much to be drawn from a project like CorpoPuente—about practice, about standards, about extending as well as meeting expectations. But perhaps the most important thing is that engaging with society, however a dancer does it, requires imagination in every aspect of practice. Far from lowering one’s vision, it demands that we raise it to match the needs, rights and aspirations of those whom we work with. Then the community dancer can be a human bridge between us all.

We artists and cultural workers in Colombia have an enormous responsibility to build these bridges, since we embody critical conscience, creativity, oneiric, playful and spiritual aspects of the society. We are the depositories of collective memory; we operate in signals, signs, indications, traces, dreams, yearnings. These are our arms and compasses. We can be bridges, messengers, mediums, sometimes soothsayers. But we artists are not magicians nor exorcists nor priests in spite of the fact that art, magic, religion and spirituality have always been closely connected.

Society believes in itself and expresses itself through its artists. Sometimes society uses artists as mirrors or magnifying glasses to take a close look at the people or as telescopes to examine the universe or as wordsmiths or spokespeople for social questions, doubts, fears and certainties.

We artists generally are privileged beings because we love what we do and we live from this love. This interior richness at times translates into material well-being. However, our greatest asset is that this difficult identity which few human beings achieve is that vocation is equivalent to profession, to passion.

Through the exercise of my craft as inventor of impulses, movements, emotions and sensations, I have come to the profound conclusion that there is no greater richness in life than being the master of oneself. To inhabit one’s body with dignity is a sine qua non condition for dignity on inhabiting the world of and with others.

It doesn’t matter what our professions or jobs are, we all are embodied in our experience, memory, emotions, tenderness, violence, ideas, deficiencies, our caresses, fears and desires…everything passes through the body.

The daily practice of my profession strengthens on a daily basis my conviction about the transformative power of art and culture as pedagogical strategies for living together in harmony. I don’t refer to art as merely entertainment or decoration. Art—with a capital “A”—is that which puts us in contact with transcendence, with a profound sense of existence. The rest is entertainment, not to be disregarded, of course. However, for a country like Colombia, where the absolute priority is to recover the sacred value of life, I believe that Art and the artists must, with our work, try to reach to the depths of the heart of the Other and to underline the fact that we all are, in essence, sacred, inviolable and transcendent beings.

Our disorientation and our anguish are symptoms of a profound ethical crisis of values. In our country, we see the human body violated on a daily basis, tortured, massacred, mutilated, assassinated. The broken body of Colombia needs to be cured: the mangled body of young Colombians, soldiers, guerrillas, paramilitaries, common criminals, defenseless civilians, children, women, old folks. Violence and the death of any Colombian, whatever his or her condition, is an irreparable tragedy and wasted human capital. The body that performs violence is almost as a much a victim as the body that is subject to violence.

We artists ought to contribute through our work, our foresight and our example, so that we can reach a peaceful agreement in this country: one of love, pardon and future. We are not afraid of these words, cynically disqualified as “social lyricism.” We have to make everyone understand that quality of life does not exist for anyone in Colombia: rich and poor, governed and governors, armed and unarmed, women and men, the elderly and the young, the executioners and their victims.

We need to reach a minimum consensus, and we need to redistribute opportunities. One of these opportunities—perhaps the most important—is access to knowledge about the inalienable and inexpugnable consciousness about our body as a natural habitat, where one can express oneself and blossom with full human dignity.

And it is here that our role is indispensable, as midwives of vocation, revealers of passion, detectors of dance. These are our missions as artists and as teachers.

Fall 2007, Volume VII, Number 1

Álvaro Restrepo Hernández is a Colombian dancer, choreographer and pedagogue. He founded EL COLEGIO DEL CUERPO (eCdC) in September 1997 with his French colleague Marie France Delieuvin.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

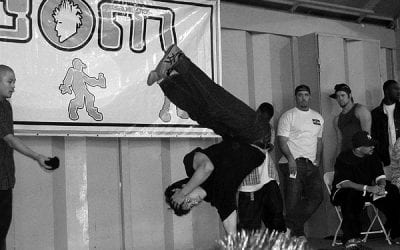

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …