Transformed Worlds

Missionaries and Indigenous Peoples in South America

Church ruins of San Miguel Arcangel. Recognized as World Heritage by UNESCO. Photo courtesy of Artur H.F. Barcelos.

In 1610, a small group of Jesuits began what would become known as one of the largest indigenous evangelism experiences in colonial America. The effort began in Asunción in colonial Paraguay.

For more than 150 years, indigenous groups who resided in the subtropical woods and forests of the La Plata River Basin were contacted by the Jesuits and came to live in nuclei called “reductions” or “missions.” The Jesuits evangelized many indigenous groups, but focused on the Guarani, speakers of Tupi-Guarani who, after a process of about 4,000 years of dispersion from the Amazon region, in the 16th century settled huge territories that now belong to Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. For decades, historians, anthropologists and archaeologists have studied the process of evangelization that got prodigious results in a colonial America where indigenous people suffered strong demographic shrinking across the continent since the early years of the conquest. To have a somewhat clearer idea how the Jesuits and the Guarani sealed pacts that allowed the foundation of more than thirty reductions, it’s necessary to take a look at these historical agents. The Jesuit order, founded in 1539 by Ignatius of Loyola, a Spaniard from the Basque region, arose in the context of the Roman Catholic Church’s reaction to the growth of Protestantism in Europe. This order, from the start, was highly selective, attracting students from wealthy families and seeking men with demonstrated high intellectual abilities at their colleges and seminaries.. In just over ten years, the Jesuits already had thousands of members and considered themselves prepared for the great task of bringing Christianity to America’s indigenous people, following in the footsteps of the Franciscans, Benedictines and Dominicans. In 1549, the first group of six missionaries arrived in Brazil, a colony of Portugal. It was the beginning of a long learning process in ways to approach and perform the conversion of the natives.

A few years later, Jesuits were also sent to the Spanish colonies, reaching the Viceroyalties of Peru and New Spain. Cultivating their great political skills and connections, the Jesuits soon were able to establish colleges and manage urban and rural properties, participate in the internal trade of the colonies and thus able to finance forays to areas where the native peoples had not yet been Christianized. With their architects, geographers, musicians, theologians, astronomers and linguists, the Jesuits served as missionaries in almost all regions of America at the service of the kings of Portugal, Spain and France, but first of all loyal to the pope.

The main goal of the Jesuits was to convert as many Native Americans as possible to Catholic Christianity. However, as they would learn in practice, and based on the experience of other orders, they realized that the best way to accomplish this would be to break with the ancestral traditions of indigenous tribes and introduce European customs and habits. Thus, the fight against polygamy, funerary practices, consumption of alcoholic beverages and, especially, the campaign against local spiritual leaders, provided some of the principal initial challenges. In contrast, the organization of traditional forms and use of space by indigenous people was also a focal point for the success or failure of the Jesuits.

Base of a wooden sculpture made by the Guarani from the Jesuit reductions. Museu Julio de Castilhos, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. Photo courtesy of Artur H.F. Barcelos.

The missionaries made many mistakes before coming to understand the best ways to convince very different groups to accept a common proposal for a radical transformation of their lives. That was also the case of the Guarani living in the tropical and subtropical forests of South America. For thousands of years, these indigenous people had practiced a way of life based on extended families, composed of a patriarch and his household—his wife, daughters, sons, sons-in-law, daughters-in-law and brothers – and sisters-in-law. These families, called Tevys, varied in size and could reach dozens of members. The Guarani economy was also organized within the families, including cultivating gardens deep in the woods. Corn, beans, squash, peanuts and cassava were the main crops. In addition to the seasonal collection of vegetables the Guarani also were devoted to hunting and fishing.

The Spaniards used a word from a Caribbean indigenous language, cacique, to refer to the principal men of these families. Among these caciques, one man assumed, eventually, the political leadership of the village. His prestige, achieved through oratory and success as a warrior, in addition to his Tevy relations network, was the guarantee of political power. However, shamans or payés, spiritual leaders of the villages, had as much or more power than the chiefs and were central figures in Guarani culture. Healings and the interpretation of dreams, along with knowledge of medicinal herbs, allowed these shamans to influence groups through their inspirational speeches, delivered at parties and celebrations. The Guarani were recognized as skilled and proud warriors by the first Spaniards who encountered them. The Jesuits recognized the Guarani as the most prepared of the indigenous groups to be Christianized. This assumption of superiority and permeability to contact is still a complicated issue for the experts. It may have been a reflection of the Guarani ability to negotiate with the Spanish colonists and the Jesuits to survive amid the violence of the invasion of their ancestral territories.

Statue made by the Guarani from the Jesuit reductions. Museu Julio de Castilhos, Porte Alegre, RS, Brasil. Photo courtesy of Artur H.F. Barcelos.

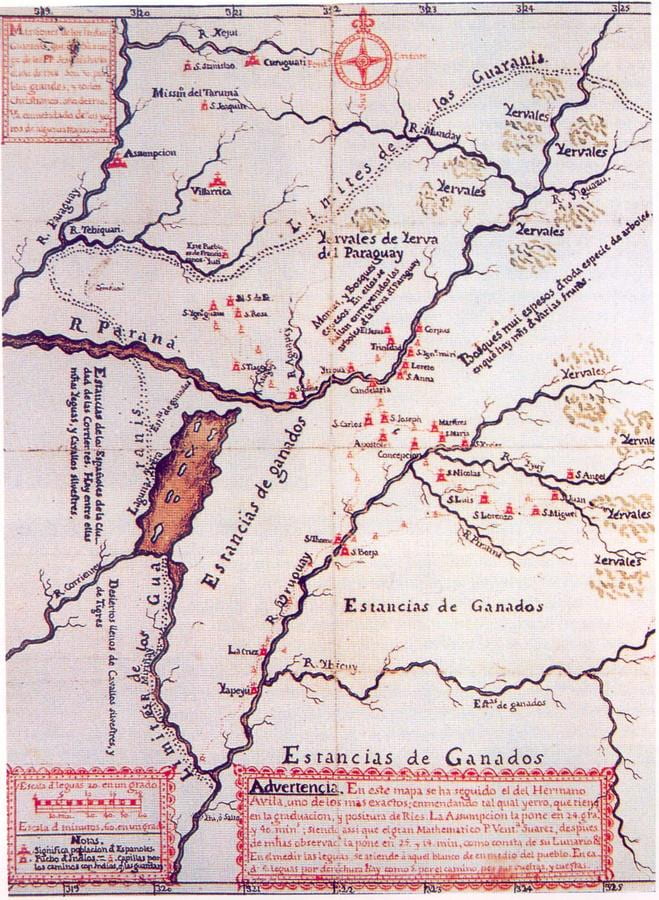

Facing the resistance of the Spanish colonists, who sought in every way to exploit Guarani labor, the Jesuits managed to found reductions in three regions: in Itatim (part of the current state of Mato Grosso-Brazil), in Guaira (part of the current state of Paraná-Brazil) and at the Tape (part of the current state of Rio Grande do Sul). These were all areas of Spanish rule under the old Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. The main obstacle came from the Portuguese possessions in Brazil. The so-called Bandeirantes, from Sao Vicente and Sao Paulo, in their forays to find precious stones and metals, as well as slave labor, launched successive attacks against the Jesuits and Indian reductions, forcing a retreat to areas closer to the Spanish cities and towns. By 1640, the missionaries had settled with the Guarani—whom they had managed to convince to come along—near the Paraná, Paraguay and Uruguay River banks, far from the attacks of the Bandeirantes. Forty years later, the Jesuits returned to the Tape, after the 1680 founding of Colonia do Santíssimo Sacramento by the Portuguese on the banks of the La Plata River directly opposite Buenos Aires. This Portuguese gesture was considered a clear affront to the Spanish Crown. It was also a central point for smuggling goods into cities like Santa Fe, Cordoba, Corrientes, Asuncion and Buenos Aires itself. Sacramento became the focus of disputes spanning nearly a century.

In this context, the Jesuits decided to work in the Tape and created seven new reductions between 1682 and 1707. Added to 23 existing reductions, the total of 30 was mostly made up of Christianized Guarani. The first half of the 18th century witnessed a strong increase in the participation of Guarani reductions in the regional market of the La Plata River. The new reductions boosted the economy, contributing significant amounts of yerba mate used as an herbal tea by indigenous people and consumed widely in the Spanish cities, where the population was primarily indigenous or mestizo. Cattle farms also supplied reductions with meat, and hides were exported to European markets. The 30 villages, with some fluctuations caused by epidemics and the constant call of the Guarani to face the Portuguese, reached a high mark of 150,000 residents.

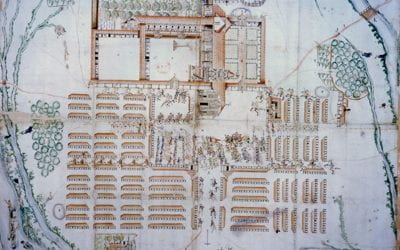

The Jesuits trained selected artisans and artists among the indigenous peoples and taught them new trades that awakened their latent talent for sculpture, woodwork, jewelry, painting and music. From this “courtyard of craftsmen” came tables, chairs, cabinets, sacred statues, paintings, silver ornaments, and musical instruments such as bass, horns, bassoons, harps, dulcimers, guitars, fiddles and flutes. The music was not just performed to delight the ears of the priests. Its role was much broader. It encouraged the religious observance, stimulated work in the fields, gave the last farewell to the dead and especially created the atmosphere for the great religious festivals held in the central square against the background of monumental churches facing single-story houses. One can imagine the effect that the incense smells, the lighting of torches and candles, the procession with the Patron Saint with music filling the air with melodic sacred chants had to the senses of the Guarani.

These centers contributed to global evangelization. In addition to rural areas of crops, resorts, rodeos, and the paths that interconnected the reductions, the Jesuits also relied on large crosses and chapels to remind the native peoples of the Church’s vigilant presence about their souls. Material benefits also provided incentives: the planting of cotton guaranteed the clothes and fabrics used for different daily tasks. Yerba mate, which previously had been cultivated in remote areas reached by the indigenous people in long and painful expeditions, began to be cultivated along the villages. The raising of sheep, mules and horses was added to the grazing of cattle. The Jesuits established ofícios de misiones, actually commercial and accounting offices, in the region’s main Spanish cities, to take care of sales and purchases for the reductions with accurate records of all procedures. The Guarani themselves exercised civil administration of the villages, occupying public offices such as mayor and chief magistrate. The militia formed by the Guarani protected the reductions and served on several occasions as the reserve army of the Spanish authorities. The Jesuits faithfully paid their annual taxes to the state, while ambitiously expanding their activities inspired by their motto ad maiorem Dei gloriam—for the greater glory of God.

This wide network of villages developed broadly by 1750, a year that the Treaty of Madrid began to contribute to its downfall. The crowns of Spain and Portugal signed the treaty to end the uncertainty of their borders in the colonial world, throwing the areas occupied by the Guarani reductions into turmoil. Moreover, the reductions became political currency for the two Catholic sovereigns to exert their respective power. The treaty proposed that seven reductions on the eastern bank of the Uruguay River would be exchanged for Colonia del Sacramento. The monarchs thus intended to put an end to the conflict of interests in the La Plata River. Indians and Jesuits were ordered to move to lands west of the Uruguay River and the seven reductions would be delivered to the Portuguese with their entire building infrastructure.

Guarani resistance to the move led to the 1754-56 “War of the Guarani” that prevented the work of the Treaty of Madrid Demarcation Committees. Defeated, the Guarani then witnessed Spanish and Portuguese troops occupy their reductions. An iconographic map of the San Juan Bautista Reduction still exists in two versions from the occupation, one in the General Archive in Simancas, Spain, and the other in the National Library in France. Both provide valuable historical sources about Guarani reductions.

Even though Treaty of Madrid was annulled in 1761, the crisis it had triggered was enough to collapse the structure of the 30 Reductions and to shake the morale of priests and Indians. The campaign against the Jesuits, which increased every day on the European continent, gained momentum with the resistance of the Guarani to the treaty. The Jesuits were accused of collaboration and encouraging indigenous revolt and they soon faced retaliation. In 1759, they were expelled from all Portuguese dominions in Europe and America. In 1767, it was the turn of Spain to take the same action. More than 5,000 Jesuits from various parts of America were forced into exile, mostly in Italy. In the early 19th century. the remains of the old reductions were already a picture of decline and desolation. The Guarani were mingling into colonial society. The independence of the Spanish colonies, which began in 1810, contributed the incorporation of Guarani territory into the spaces of the new nations. Some reductions became towns; others remained in ruins amid the forests and fields of Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay. Today, some of their remains are local tourist attractions, where they evoke a glorious past. However, the excitement visitors feel on seeing the ruins of imposing churches does not translate into an understanding of the historical destiny reserved for the Guarani and other indigenous peoples from other latitudes of America—peoples that today struggle to have their land rights recognized and their cultures preserved. As much as the Jesuits attempted to ensure the survival of Guarani who accepted the conversion and life in reductions, their extreme zeal and natural distrust of the political and intellectual abilities of the indigenous people did not allow a true emancipation.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Artur Henrique Franco Barcelos, a historian and archaeologist, teaches archaeology at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande—FURG, Brazil. He is a specialist in the history of the Jesuit evangelization in colonial America. He is the author of O Mergulho no seculum: exploração, conquista e organização espacial jesuítica na América espanhola colonial (2013) and Espaço e Arqueologia nas Missões Jesuíticas: o caso de San Juan Bautista.

Related Articles

Jesuit Reflections on their Overseas Missions

When you think of Jesuits in their missions around the world, you—the casual reader—might not think of Plato or ancient Greek authors. Yet two of these…

Paraguay: Un país en una lengua misteriosa y singular

English + Español

If you arrived in a country where almost 90% of the inhabitants speak Guarani, an official and national language along with Spanish but do not identify themselves as “Indian” or aboriginal…

Territory Guarani: Editor’s Letter

DRCLAS receptions are bustling affairs, sparkling with ample liquor, Latin American tidbits and compelling conversations. It was at one of these receptions that Jorge Silvetti and Graciela Silvestri first approached me casually regarding an issue about the Guarani…