What Powers Latin America?

Patterns and Challenges

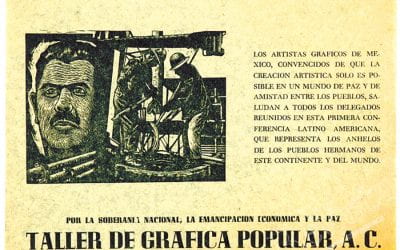

Transportation is the largest energy consumer in Latin America. “EL TREN DESDE MI AZOTEA” by ADEMIR ESPIRITU/OJOS PROPIOS, Lima.

Between the Rio Grande and the Strait of Magellan lie the world’s largest crude oil reserves, giant natural gas reservoirs, plentiful mineral deposits, massive rivers and even volcanic activity yielding geothermal power. However, knowing that Latin America has plentiful energy wealth is a necessary but insufficient condition to analyze its energy market.

Important cleavages exist within the region. Caribbean nations rely almost entirely on imported oil products to power lights and transport people, while Andean nations are huge net exporters of crude oil, natural gas and coal. Some countries in Latin America are completely exposed to market forces, while other countries offer generous subsidies.

So how does the general picture look and what is the way forward for Latin American energy markets over the next decade, in terms of new technologies, reforms and regulatory changes?

To put Latin America into context as an energy producer and consumer, we compare it to the United States, China and India to bring to the forefront some of the more salient issues for the region. The comparison with United States and China is important because these two countries are the largest energy consumers in the world, while India consumes roughly the same amount of energy as Latin America and the Caribbean.

A caveat: comparing energy data is intrinsically difficult. Natural gas is measured in British thermal units while coal is measured in millions of tons. Crude oil is bought and sold as barrels per day and electricity consumption is quantified by gigawatt-hours. The disparity in units is only one part of the problem. Another problem is definitions: industrial consumption in one country may be defined as commercial consumption in another, to name but one example. We will thus rely on data from the International Energy Agency that is homogenized and therefore comparable across time, countries, sources and sectors.

THE LATIN AMERICAN ENERGY MATRIX

The transportation sector is the largest consumer of energy in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) with 36% of its total energy consumption. This is also true for the United States (42% of its total) but it is not the case in India, where the largest consumers are residences of all sorts with 36%, or in China, where industry consumes 44% of all energy. It is a generally recognized pattern: as a country develops, it moves from using most of its energy for cooking meals and heating homes to powering factories to moving goods and people.

The literature also clearly indicates that the wealthier a country is, the more energy it consumes per capita, with most of that energy used for transportation. Indeed, Latin America’s largest consuming sector changed in the early 1970s when industry replaced residential use as the region began to leverage its natural wealth—particularly in hydrocarbons—and many people migrated to cities from the countryside. The second transition took place in the mid-1990s when the industrial sector yielded its first place to transport as LAC began seeing higher levels of wealth per capita.

However, a more in-depth analysis reveals that this consumption pattern for Latin America does not hold true across the board because its regions are radically varied. We can split LAC into four parts: Southern Cone, which includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay; the Andean region, made up of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela; and the Central American isthmus, where we have Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama. Mexico is a geographical region unto itself. The Caribbean includes Haiti, Dominican Republic, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and the Eastern Caribbean.

The Southern Cone consumes energy mostly for industrial purposes with 35% of the total and for transportation at 34%. This is a heterogeneous group as Chile, Uruguay and Brazil have higher industrial use than transportation but Argentina and Paraguay use slightly more energy for transport than industry. The patterns of consumption are not the only differences. Chile, for example, is a net importer—by a wide margin—of fossil fuels. Indeed, domestic production is only 30% of energy supplied to the Chilean market—a pattern expected to remain over the next decade.

Uruguay is similarly reliant on international energy markets. It does not produce oil or gas but imports both, along with about half of the oil products it consumes, as it has one refinery that supplies the remaining share. Paraguay is at the opposite end of the spectrum, as it actually exports to Brazil and Argentina 80% of the electricity it generates and imports about one third of the energy it consumes, which is mostly made up of firewood and other biomass products.

The giant in the grouping is Brazil, which accounts for 70% of Southern Cone energy consumption. Brazil is famous for its production of biofuels—started as a security policy in the late 1970s and now a pillar of Brazilian policy—but it is also the third largest producer of oil and fourth producer of gas in Latin America. Brazil’s use of hydroelectric power is also the highest in all of Latin America and it is one of only three countries in the region that use nuclear power (Mexico and Argentina being the other two). It also leads the region—by some margin—in the use of non-conventional renewable energy sources like solar and wind.

In contrast to the heterogeneous south, the Andean countries are all similarly blessed with plentiful energy wealth. Bolivia and Peru boast large reserves of natural gas that began to be extracted over the past two decades. Energy use in Bolivia is evenly split between industry and transport, while Peru’s is more tilted towards transport.

Colombia’s high-quality coal in the northeast and heavy crude oil in the south and southeast are plentiful and should serve the country well over the next decade, though there is pressing need for investment in exploration. Due to its difficult geography and its income level, transport is the largest consumer of energy in Colombia.

Ecuador’s energy matrix is almost completely dominated by producing and exporting crude oil. Buoyed in part by a subsidy scheme that is about 7% of GDP, the transport sector is by far the largest consumer of energy in Ecuador with 50% of the total.

Venezuela’s certified oil reserves are the largest in the world, and it also has Latin America’s largest gas reserves and powerful, dammed rivers that provide hydroelectric power to its grid. The lowest price of gasoline in the world explains why transport energy use is 35% of the total and three times larger than residential usage, but it is industry that takes top billing with 49% of the total.

Energetic homogeneity also exists in Central America but in the opposite sense. Central America imports a whopping 40% of the energy it consumes, while another 40% is made up of firewood and byproducts from sugar-cane production. It is no surprise that as the poorest region by income in Latin America, most of Central America’s energy use is in the residential sector with 42% of the total, and transport a distant second with 30%.

Residential consumption is such a large share of Central America’s total energy use because its rural areas have not been integrated to the electricity grid so residents burn firewood. Rural electrification programs have gone a long way towards bringing modern energy to remote populations throughout Central America and elsewhere in LAC in order to reduce the use of firewood, but much work remains to be done.

The case of the Caribbean island nations is similar and more dramatic than that of Central America. These nations generally lack domestic sources of energy, with the notable exception of Trinidad and Tobago, an important producer of natural gas. Their reliance on imported diesel and fuel oil makes them uniquely vulnerable to market ebbs and flows, but there is little alternative. Domestic sources have been tapped where available—small rivers in Jamaica, Haiti and Dominican Republic have been dammed, for example—but they will continue to depend on external supplies of energy.

THE ELECTRICITY MARKET

The salient feature of Latin American electricity is the widespread use of hydraulic energy. Indeed, nearly 52% of all electricity generated below the Rio Grande is from hydropower. The region’s distant second source of electricity is natural gas with 24%. This reality, however, is changing as most of the large rivers with hydrogeneration potential have been dammed. While there is some space for growth still, particularly through refurbishing old facilities, developing virgin river basins and installing small hydropower stations, over the next ten years hydraulic power will lose some of its preponderance in the Latin American electricity market.

Candidates to take market share from hydropower include a variety of sources. In Central America, geothermal power has become an integral part of the electricity mix and will continue to grow. Solar, wind, and other non-conventional energy sources have grown tremendously in Brazil, Mexico, and Chile since their introduction to LAC in 1992, though today they only represent 0.7% of electricity generation. Nuclear power facilities exist in Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina and though very tentative plans to introduce nuclear plants exist, the prospect for this source is not good.

Diesel and fuel oil plants have been installed to meet growing demand throughout LAC as they are accessible in terms of capital requirements and cheap to operate and maintain. These plants, however, have high environmental costs and Latin America is well known for its low-carbon consumption: its CO2 emissions per unit of GDP are the lowest in the developing world and only slightly higher than those for the EU or the OECD.

The more long-term, cost-effective, and environmentally sustainable source for electricity generation in the face of dwindling hydropower is natural gas. It is an energy efficient investment to refurbish existing oil-powered plants to burn natural gas instead, and the installation costs of natural gas facilities are lower than coal. The region’s reserves of gas make it a uniquely suited fuel as demand continues to grow and rivers can no longer supply sufficient power to the grid.

Venezuelan oil refinery. Photo by Nelson Garrido, nelsongarrido@gmail.com, nelsongarrido.blogspot.com

INSTITUTIONS AND POLICY

As the region embarks upon these infrastructure investments, we must remember that over the past century most countries have wisely chosen to leverage their comparative advantage of natural resource endowments. The degree of successful exploitation certainly varies in the sense of the sustained developmental impact of natural resource extraction.

Economic diversification is a wise policy recommendation for the entire region, but it must be understood that on a global scale, Latin America will continue to be an important supplier of commodities and raw materials to the global market. Its valuable resources give it a special comparative advantage over other regions. This does not mean that it will simply be a mine and an orchard to the world, however. Natural resource extraction can foster the development of value-added industries, as in the case of Finland and Nokia or Sweden and Ikea, two valuable companies born out of the timber industry.

In order to continue to extract these resources in the most competitive and cost-efficient manner, best practices from the Latin American experience have shown that private investment must accompany public funding, in a manner that is open, transparent and competitive. This is true for electricity generation and fossil-fuel production, as these sectors require massive, risky, long-term capital investments that the state generally cannot finance alone.

The ideal arrangement—borne out by experiences in Brazil, Peru, and Colombia—is to encourage private investment under strong regulatory agencies that open the sector to private capital under clear, credible and fair rules. This is the model that Mexico is following under its current reform process. The main benefits from such a model are that it attracts capital, ensures competition and transparency, permits access to best practices and state of the art technologies, exposes the sector to market prices and limits monopolistic behaviors.

A second reform need concerns subsidies. Partly as a result of its resource base, many countries have implemented subsidy programs aimed at lowering the costs of electricity and transportation fuels to the general public. However, research shows that there is a high correlation between income per capita and energy consumption, that is, the richer you are, the more you energy you use. Therefore, the better-off segments benefit more from indiscriminate subsidies. Aside from the regressive nature of energy subsidies, the lack of exposure to prices can lead to smuggling and widespread energy waste, which results in environmental damage.

Clearly defined and targeted subsidies can exist if they secure access to electricity and cleaner-burning technologies such as efficient cooking stoves. In the transportation sector, subsidies can be beneficial when aimed at fostering the use of mass transport. The region would do well to continue to remove across-the-board subsidy programs that still exist and to design more tailored and efficient cost-alleviation programs.

A third area with space for reform is regional energy integration, particularly impactful in small markets. In Central America, integration has proven to be excellent policy by yielding economies of scale required to introduce lower-cost generation facilities that lead to fairer pricing and better energy supply.

Latin America cannot simply rest on its energy-rich laurels. It is lucky to have plentiful traditional and non-traditional energy at its disposal, but it must move without hesitation towards more nimble and attractive institutional arrangements if it is to derive gains that equally benefit the region’s poor and rich.

Official data and expert estimates place the required investment to expand the region’s electricity generation in the next decade at about US$300 billion. The monies needed to increase oil and gas production reach above US$1 trillion. None of this investment will be possible without a strong partnership between the public and private sector. Our own experience shows that this understanding is possible and beneficial. The challenge is immense, but achievable.

Fall 2015, Volume XV, Number 1

Ramón Espinasa is the lead oil and gas specialist at the Inter-American Development Bank and an adjunct professor at the School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University. He holds a Ph.D. in energy economics from the University of Cambridge and an industrial engineering degree from Universidad Católica Andres Bello. He can be reached at ramonespinasa@gmail.com

Carlos G. Sucre is a consultant at the Inter-American Development Bank and an adjunct professor at the School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University. He holds a Master’s degree in international affairs from the Elliott School of International Affairs of George Washington University and an economics and political science degree from the University of Chicago. He can be reached at carlos.sucre@gmail.com

Related Articles

Oil and Indigenous Communities

On a drizzly morning in late February, a boat full of silent Kukama men motored slowly into the flooded forest off the Marañón River in northern Peru. Cutting the…

Mexico’s Energy Reform

The small, white-washed classroom at the University in Minatitlán, Veracruz, was packed with a couple dozen people who, although neighbors, had never met…

Geothermal Energy in Central America

When we think about global technology leaders, Central America does not typically come to mind. But Central American countries have indeed been in the…