Boycott as Political Instrument: the case of Guatemala

From Eternal Spring to Eternal Tyranny

Photo by Jean-Marie Simon.

After spending much of the previous six years traveling through Guatemala, photographer and writer Jean-Marie Simon published Guatemala: Eternal Spring, Eternal Tyranny (1987). This book was intended to illustrate the daily reality of contemporary Guatemala to an international, primarily North American, audience. Simon begins by juxtaposing, what are among Guatemalans and Guatemala analysts, familiar phrases – the combination of which points to the underlying “Truth” and tragic irony of the story she is to tell.

In the 1800s a European visitor called Guatemala the “land of eternal spring.” A century later, Guatemalan essayist and politician Manuel Galich called his country the “land of eternal tyranny.” For a few Guatemala is paradise. For most, it is not.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, the glossy oversized cover of Simon’s book beaconed us from our overstuffed chairs in our living rooms to spend a lazy hour thumbing through what seemed to be a beautifully illustrated travelogue of exotic adventures in far away places. But this unconventional coffee table book provided no such relief. Fifteen years later, it still does not. Once the cover is lifted, the reader is shocked to find that they have not embarked on a trip to a Latin American Shangri La, but have plunged into Central America’s killing fields. Using written narrative and visual images, Simon guides her audience through the rugged socio-political landscape of Guatemala during the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

While it did attempt to make its reader stop and pay attention, the goal of Simon’s book was not to create a sense of paralysis. Indeed, it was quite the opposite. It was a call to conscious and action—one of many that had gone out during the previous ten years seeking to build international solidarity with Guatemala. Like many tours, its objective was to expose its armchair participants to the unknown, provide sufficient information to help them interpret what they are seeing, and in so doing transform them. Both in form and content Simon simulates this process, all the while delivering a crucial message: As physical, material and brutal as it has been, Guatemala’s conflict has not just been a war between people of different ethnicities and classes, fighting for access to basic resources such as land. It has been a bitter global struggle over ideologies, information, images, and the frames through which to interpret them, involving both coercive and non-coercive methods. Therefore, to be successfully resolved, the conflict must be dealt with at many levels, on many fronts, using both conventional and non-convention weapons.

SELLING BEAUTY AND PLEASURE IN THE LAND OF ETERNAL TYRANNY

By the late 1980s, when Guatemala: Eternal Spring, Eternal Tyranny was published, juxtapositions of extremes and of “images” vs. “Reality” had become standard tools in Guatemala solidarity work, as had boycotts. Throughout the 1970s, international human rights campaigns had been working to establish alternative frames of reference for analysis. They sought to leverage the power of international markets through economic support measures, embargos, and boycotts. These tactics had become accepted non-military intervention strategies—used by both the right and the left—to shift the policies of foreign governments and commercial sectors.

In 1979, the International Union of Food and Allied Workers (UNI), an international body comprising 160 national unions of food workers in hotels, restaurants, cafeterias and travel agencies in 59 countries, decided to utilize these strategies and go a step further. On December 6th, the UNI called for a tourist boycott of Guatemala based upon human rights violations perpetrated by the government against its citizens. Its decision to target the tourism industry was strategic in that it attacked one of the few sectors within Guatemala that was still growing: from 1975 to 1979 the number of tourist coming into Guatemala rose steadily, if modestly, from 454,436 to 503,908. It was unique in that it pushed international consumers to question travel as an individual right and abstract ideas such as beauty/pleasure, horror/pain and the right to them or to be free from them.

The UNI’s call to boycott tourism to Guatemala had a catalytic effect in mobilizing the Guatemala international solidarity movement. It expanded the network by leveraging its bargaining power as an international union, inviting member countries to join them in dissuading potential tourists. Both in agreement and to avoid labor conflict, many European travel agencies joined them. Non-industry linked Guatemala solidarity committees in the U.S. (i.e., Guatemalan Solidarity Network, Guatemalan News and Information Bureau) and Europe were soon to follow, distributing posters, public advertisements and bumper stickers with headings “Protect Human Rights, Don’t Visit Guatemala.” Larger human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, published special reports on human rights violations in Guatemala, and sponsored public information campaigns including brochures and news bulletins, providing local committees and news agencies with the official documentation necessary to back their claims. By 1980, news coverage of the political situation had increased in the U.S and overseas.

As the boycott gained support and reports of the repression under General Romeo Lucas García (1978-1982) increased, the number of tourists traveling to Guatemala plummeted. In 1980, the number entering the country dropped below 1975 levels. The industry continued to suffer through 1981, during which tourism decreased 55%. By 1980-81, hotel occupancy rates had fallen to 43%, a significant drop from the 70% maintained for the same period in 1979-80, and the 80% it averaged in 1970. Unable to continue paying maintenance costs without income, many related businesses fell into debt, laid off workers or closed their doors – some temporarily, others permanently.

To counter the IUF tourism boycott, subsequent U.S. State Department travel advisories and ongoing international advocacy, numerous members of the Guatemalan government and the national tourism industry, public and private, responded with their own campaign denying that tourists were unsafe. While admitting the country’s difficulties at the time, these pro-government advocates pointed out that Guatemala had socio-political problems no worse than Ireland, Italy or the Middle East. They charged that they were being unfairly singled out for U.S. scrutiny, as was the U.S.’s historical tendency in dealing with its southern neighbors. The importance of Guatemala’s national sovereignty was invoked, as was the ECLA era Latin American critique of U.S.’s inability to support its neighbors when they were dealing with internal crises and factionalism. A number of these communications recommended that foreign advocates focus on the bountiful social injustices of their own governments and social systems and leave Guatemalans to the job of caring for their own people. The international left paused in shock as they watched Guatemala’s right appropriate many of its anti- and post-colonial arguments. Negations of clear human rights abuses, however, overshadowed whatever historical veracity these other claims held and resulted in even stronger international support for sanctions.

As the income from tourism, which had been one of the country’s leading industries, slowed to a trickle, industry agencies recognized that they must, in order to survive, find new economic strategies to fight the boycott. At the 1981 National Convention of Hotel Owners in Quetzaltenango, private and public agencies sought a sector-wide solution, appealing to the government for aid in promoting Guatemalan tourism abroad. Due to lack of national funds and the pressing priorities of the war, few of these plans progressed beyond the inquiry stage. Frustrated and struggling to regain some of its lost foreign market, the Instituto Guatemalteco de Turismo (INGUAT), in 1981, agreed to pay New York public relations firm Needham and Grohmann U.S.$1.5 million to launch an international campaign to counter the boycott. The agency had little success. In 1982 the industry generated only U.S.$60 million, significantly lower than the pre-boycott U.S.$132.4 million it grossed in 1979.

Despite continued efforts by international organizations to curb human rights violations and by the Guatemalan government to convince the international public that Guatemala was safe, little changed during the administrations of Generals Efraín Ríos Montt (1982-82) and Oscar Humberto Mejía Victores (1983-85). It was not until 1985, when the increasingly isolated Mejía Victores government conceded to hold elections, that the stalemate was broken. With the promise of a “return to democracy” and the inauguration of civilian president Vinicio Cerezo in 1986, solidarity organizations and the international media relaxed the campaign and allowed the effects of the boycott to subside. Results were rapid: In 1986 totals increased by 14%; in 1987 they rose another 23%. By this time however, the Guatemalan industry had turned its attention away from the U.S. and begun pursuing more elite European markets, Italy and Germany being the two largest, neither of which, incidentally, had issued travel warnings during the previous years.

CREATING A “COLORFUL AND FRIENDLY” GUATEMALA AND AN ALTERNATIVE MUNDO MAYA

Much of the post-Peace Accords work in Guatemala today focuses on the documentation of human rights abuses. Even during times of relative peace, this is a difficult job. Fighting against silence, over competing memories, indigenous and ladino leaders work with national and international human rights commissions to define the way Guatemalan history will be written and remembered. Participants are aware that the narratives they are constructing will play a critical role in defining their county’s future. As painful and traumatic as revisiting the past is, what scares survivors most is the idea that it could be forgotten. In this context, the images and texts featured in glossy tourism brochures represent much more than pleasure-seeking apolitical escapism. They are guides to understanding highly politicized power relations and the testing ground for alternative national landscapes.

During the 1970s and 1980s, when the war raged in the highlands, tourism brochures offered a space where the state could successfully pacify the Other. Despite the increased coverage of political violence, the collapse of internal markets, and the government’s growing isolation, attractive brochures similar to those printed in the early 1970s continued to be produced, inviting tourists to visit this “peaceful country.” It was during this conflictive period that “Colorful and Friendly” Guatemala became the central building block of INGUAT’s ethnic tourism campaign, a marketing tag that would last well into the late 1990s. Visual representations of smiling men, women and children dressed in “traditional” traje decorated brochure covers, complementing condensed histories of “the Maya,” descriptions of what they eat, wear, speak and other details about their “fascinating” and “mysterious” way of life. Purged of all signs of profanity, disorder, chaos and aggression (misery and poverty) that signify the anxiety-provoking “bad other,” these images were homogenous enough to be placed into the category of Indian (natural, timeless, geographically remote, mysterious), yet heterogenous enough to still be interesting (regional uniqueness). In these texts, cultural pluralism and peaceful coexistence take the place of ethnocracy, genocide and civil war, and happy female petty commodity producers replace the angry “subversive” male rural guerrillas portrayed by the military. Thousands of years of conquests and ideological conflict disappear in the bustling activity and productive exchange of the age-old highland marketplace. These were the state’s reassuring images of immediate post-Cold War Central America, but they would not last.

By 1986 the Guatemalan tourism industry had already begun to show signs of change, adapting travel packages to “alternative” tourism, the industry’s response to the recent growing consciousness about the world’s social and environmental problems. In Guatemala, these alternative packages took the form of “soft-foot” and “eco-tourism” projects such as the Mundo Maya. In 1990 Alberto Rivera, one of the first INGUAT consultants to the Mundo Maya, explained that while pictures of smiling indigenous people in traje commonly seen in earlier promotions were still necessary, they were no longer sufficient. The program plans for the Mundo Maya would produce a new kind of tourism for Guatemala based on the creation of more individualized, “unique” and “authentic” experiences for greater numbers of wealthier tourists. Two years later, the indigenous people who had been featured on brochure covers and posters were just one of the sights/sites in a rapidly expanding panorama of national attractions such as nature reserves and recently restored archeological sites.

Yet, one of the goals of the tourism boycott had been to keep the image of indigenous Guatemalans in the public eye and in that way to keep the Guatemalan State accountable. As the gaze of the international human rights community shifts to struggles in other countries, the risk for indigenous Guatemalans is not misrepresentation (the “images” vs. “Reality”), but total erasure. “My fear,” confided Alberto Gomez Davis, the then director of INGUAT’s Patrimonio Cultural, “is that we are just preparing for the next time it happens. Only, this way, afterwards there will be no need for Indians.”

Winter 2002, Volume I, Number 2

Related Articles

Restoring a Ravaged Venezuelan Coastline

Dramatic floods ravaged the Caracas seaside known as the Littoral in December 1999, ripping up houses and literally re-shaping the coastline and beaches. Less than a year later, I joined several …

From Trek Leader to the Research Track

I earned a living for many years making the world a smaller place. I led treks into the remote and mountainous terrain of Nepal, India, Bhutan and Tibet, escorting small armies of intruders from North America …

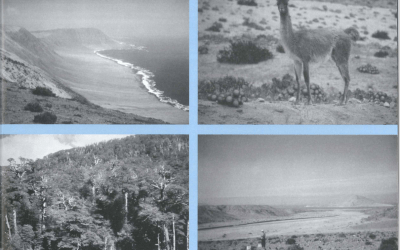

Ecotourism in Chile

From the point of view of a scientist, the worldwide surge in ecotourism is a mixed blessing. On the one hand, who can deny that interest and exposure to nature ecosystems provides an …