Burning Messages

Antonio Berni’s Provocative Trash Aesthetic

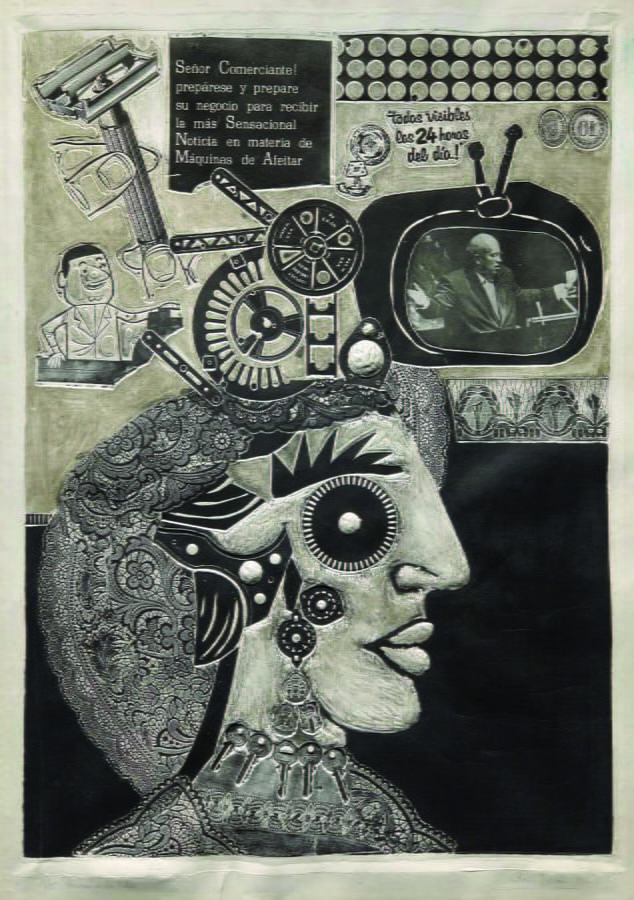

La sordidez, de la serie Monstruos cósmicos, c. 1964. Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. © José Antonio Berni.

A bomb exploded at the entryway to artist Antonio Berni’s home and studio in Buenos Aires early one morning in 1972. Fortunately no one was injured: the artist was away in Paris, his wife startled but safe in their bedroom a few rooms away from the blast. Why had Berni been targeted? And by whom? Initial news reports speculated that terrorists had bombed the wrong address, intending to hit a nearby government building. But nowadays most agree the bombers were aiming for Berni and were part of an anti-Communist terrorist group—possibly a precursor to the infamous Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, or Triple A, a secret government-affiliated death squad that carried out assassinations and illegally detained intellectuals and rival political leaders during the Dirty War of the 1970s. Berni, briefly a member of the Communist party in the 1930s, had long sympathized with the left. But in all likelihood the attack on his home was not prompted by his political affiliation, but rather by his artwork and the powerful critical message contained within.

Ramona en la calle, 1966, xilo collage relief. Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. © José Antonio Berni.

At the time of the bombing, Berni was arguably at the height of his career—one that stretched during much of the 20th century. In the 1930s and 1940s, he had gained national recognition for leading the country’s Nuevo realismo, or New Realism, movement, channeling his exceptional skills as a painter to create mural-sized scenes about working-class life in the era of the Great Depression. During the 1960s and 1970s, Berni’s prominence reached new heights, above all for his series about two fictitious characters, Juanito Laguna and Ramona Montiel. In this series, Berni transformed trash into imaginative visual narratives about contemporary Argentinean realities. Narrating episodes of Juanito’s and Ramona’s lives in a non-linear sequence, these works epitomized the artist’s creativity and his mastery of materials. Through them, he wove together controversial content and form to create a tightly knit set of social and political commentaries that resonated with the Argentinean public.

Berni began developing his idea of Juanito, a boy living in the shantytowns on the fringes of Buenos Aires, around 1959-1960. Berni later explained on a 1977 album about his character, which he co-created with musician César Isella: “When I first started sketching scenes of the poorer neighborhoods I used to look at the barrio kids and felt that my character lacked an identity of its own. So I decided to give him a name; I wanted to name the character, this archetype of all those children of greater Buenos Aires and all the little boys in every Latin American city. He could be from Santiago, Lima, Rio de Janeiro, or Caracas….” Like many Argentinean families at mid-century, the fictional Laguna family had migrated from the countryside to the capital city in search of jobs and better lives, only to find that the available work—mostly menial and low-paid factory positions—forced them to live on the margins. Berni constructed images of Juanito and his family from a variety of found trash taken directly from the streets of actual shantytowns: corrugated metal, factory waste, broken toys, damaged electronic components, dirty cloth scraps, tin cans and various other pieces of garbage. In a representative example from the series, Juanito Goes to the City (1963), we see a life-sized Juanito made from discarded clothing, plaster and paint, his hair likely strands of an old broom. He wades through a pile of garbage on his way to the city center, perhaps in search of work, or to bring lunch to his father, the metal worker, as the title of a different assemblage announces. Rows of buildings and a diesel truck (viewed oddly from the rear) appear at mid-ground. An ominous grey cloud hangs over the scene. Yet, despite his miserable surroundings, Juanito is not to be viewed purely with pity. Instead he perseveres, being an underdog with street smarts. As Berni reminded interviewers, “Juanito is a boy who is poor, not a poor boy.”

uanito ciruja, 1978. Image courtesy of Malba-Fundación Costantini, Buenos Aires. © José Antonio Berni – Luis E. De Rosa.

At the same time that Berni created assemblages of Juanito, he also invented his own form of printmaking—techniques he called “xilo-collage” and “xilo-collage-relief”—that incorporated trash materials into his woodblocks; the resulting paper prints contained rich surfaces of embossing and debossing. In 1962, Berni won first prize for printmaking at the prestigious Venice Biennale, where he showcased several assemblages and large xilo-collages depicting Juanito fishing, hunting and bathing in the abandoned areas nearby factories. With his prize money, Berni set up a studio in Paris and began developing his second protagonist, Ramona Montiel, a lower-middle-class girl, raised Catholic, who worked as a seamstress to support her family. Motivated by desires for the finer things in life, Ramona became attracted to the glitz of nightlife, working as a cabaret dancer and eventually a prostitute. Ramona served as a prism through which Berni explored conflicting societal pressures and desires. Judged for selling her body, Ramona is also a powerful heroine who uses her sexuality to gain influence and wealth.

Like Juanito’s, Ramona’s narrative takes place in Buenos Aires, but there are key differences between them: whereas Juanito was the subject of various assemblages, Ramona’s narrative unfolded primarily through prints. Also, Berni chose to incorporate different materials into his Ramona works, namely, images from fashion magazines, pieces of lace, plastidoilies and furniture pieces that he scavenged in Parisian flea markets and that spoke to Ramona’s material conditions and her desire for glamour.

For nearly twenty years, Berni alternated between creating images of Juanito and Ramona, using each to address a different set of timely subjects. (In fact, they do not appear together in Berni’s work). Through Juanito, Berni reevaluated trash, literally bringing it into established art centers and encouraging art collectors and the elite to confront images of the poor and downtrodden, people who generally go ignored. As evidenced by Juanito the Scavenger (1978), Berni’s boy hero lives with pollution and environmental waste generated by mass consumerism. He makes do, even when he appears powerless. Through his Ramona series, Berni turns his attention to social hierarchies and pressures confronting modern women. He created various portraits of Ramona’s suitors and protectors, her so-called “friends.” These images, perhaps some of Berni’s most satirical, present a cross-section of Argentinean society: here are religious leaders, a spiritual psychic, an aristocrat, a mafia thug, a bourgeois couple named Mr. and Mrs. Pérez, and various military men, all with their own agendas for Ramona. Some are caricatures of recognizable figures, such as The Sailor (1963), which exaggerates the pointed nose of admiral Isaac Rojas, who helped overthrow Juan Domingo Perón in 1955. In the mid-1960s, Berni also created large monsters of trash, generally understood as characters from Ramona’s nightmares. With titles like Sordidness, Hypocrisy, and Voracity, they embody the deadly sins consuming modern society. Darkly comedic, the monsters are at once amusing and general indictments of the people in power as well as of the common man.

Juanito va a la ciudad, 1963. Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. © José Antonio Berni – Luis E. De Rosa.

Given Berni’s unflinching aesthetic, perhaps it’s not surprising that he became the target of a bombing attack as the country entered the worst periods of military dictatorship. In retrospect, it seems the bombers were destined for failure. They could not turn into rubble what was once trash in the first place. In fact, Juanito and Ramona grew beyond Berni’s control to become folk heroes. By the mid-1970s, Berni recalled seeing “Juanito Laguna” painted on the back of trucks. Folk singers including Mercedes Sosa created music about Juanito, and some of the nation’s most influential writers, including Ernesto Sábato, wrote versions of Ramona’s story. These characters’ popularity continues today. They appear in school plays and text books, but also have Facebook fans and appear animated in YouTube videos. Yet, the problems that Juanito and Ramona faced—including class and gender discrimination, pollution, government abuses of power—refuse to diminish. And so their relevance only grows.

Winter 2015, Volume XIV, Number 2

Michael Wellen is a curator of Latin American art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and coorganized Antonio Berni: Juanito and Ramona, the first major traveling exhibition of Berni’s work to appear in the United States in nearly 50 years. View the exhibition at Malba–Fundación Costantini, Buenos Aires, until Feb. 25, 2015. Contact: mwellen@mfah.org

Related Articles

Garbage: Editor’s Letter

Religion is a topic that’s been on my ReVista theme list for a very long time. It’s constantly made its way into other issues from Fiestas to Memory and Democracy to Natural Disasters. Religion permeates Latin America…

Buenos Aires, Wasteland

English + Español

Walking down Avenida Juan de Garay last week, I passed a giant black trash bag that had ballooned and burst. Orange peels, tomatoes, candy wrappers…

First Take: Waste

Waste—its generation, collection and disposal—is a major global challenge in the 21st century. Cities are responsible for managing municipal waste. Solid…