Carnaval in the Dominican Republic

A Stew of Cultures

I stand mesmerized by the flashing fangs and devilish eyes of the mask, topped with spiked horns and kaleidoscopic mane, worn by a whirling, dancing costumed figure in the street. Suddenly a bruising smack breaks the spell. I am hit hard on the leg by a pig bladder gripped by a laughing—and now running—10-year-old boy—an abrupt welcome to Carnaval in the Dominican Republic!

Just as in New Orleans, Rio de Janeiro or Port-au-Prince, every resident of the Dominican Republic seems to look forward each year to Carnaval. Each major city or town has a distinctive look or theme to its costumes. Neighborhood groups design and construct new costumes each year, spending months working on them. When Carnaval arrives in the days before Lent, the costumes are worn in town parades, and participants also often later travel to enormous combined parades in the capital city of Santo Domingo, and recently in Punta Cana in the east. Dominican Carnaval celebrations traditionally occur throughout February, and peak around Independence Day, February 27, earlier than in other countries.

As an ancient tradition based on Catholicism, Carnaval often begins on the Sunday before Ash Wednesday, with feasting on the aptly named “Fat Tuesday,” the day before Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent, and the following 40 days of fasting before Easter Sunday. In the early colony that was to become the Dominican Republic, these days before Lent were known as “carnolestadas,” or days of much meat. The very word Carnaval itself means full of meat, signifying an indulgent time of much carnal consumption before the cleansing abstinence of Lent.

Over the 500 years since its beginnings in Catholic Europe, Carnaval has come to include cultural elements from many sources, particularly from Africa through the population that arrived as slaves, but also from native America and popular culture. Among the early images are those of the devil, still seen in the masks of the town of La Vega and elsewhere, the bronzed skins and loinclothes of the indigenous Taino, seen in Puerto Plata, and in the distinctive animal heads of Salcedo. They are joined by icons from popular movies such as Star Wars or Predator, as well as themes of protest.

Since the beginning, Carnaval has been a relatively safe means to express dissatisfactions, for political protests and even rebellion. For example, a recurrent presence over the decades is a figure of a towering Uncle Sam (a personification of the United States ostensibly dating to the War of 1812 or earlier) invariably portrayed on stilts. Among the current political themes is the symbol of four percent, alluding to the constitutional requirement that four percent of the national budget be allocated to education (and showing dissatisfaction with lower percentages).

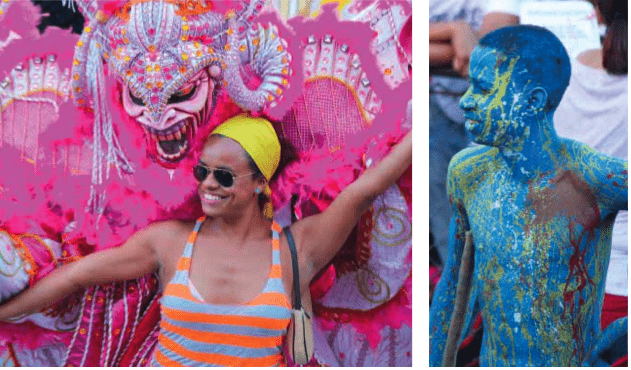

Thus, the Carnaval is a stew of cultures, a mix of the old and new, the costumes and dances a freewheeling admixture of images and textures in motion. Enormous banks of speakers on roadside platforms blast deafeningly loud merengue, often written for Carnaval, and other Latin music. The crowd is many deep on both sides of the street, with occasional openings created by charging diablos swinging the inflated dried pig bladders called vejigas. Stands with ice-cold Presidente beer are ubiquitous and highly visible, and the larger towns and cities set up portable bandstand seating. The parades are open to everyone who wishes to participate, whether in groups known as comparsas or as individuals. This freedom of expression has characterized Carnaval since its colonial beginnings, when male and female participants dressed in masks and costumes that blurred their genders as well as their identities. Freed from recognition, individuals threw water and eggs and generally created joyous havoc in the days before the somber weeks of Lent. The original themes from Spain and other colonizing countries often included devils and angels. In particular, the green, red and yellow colors of St. Michael the Archangel are predominant in the elaborate costumes of the devils known as diablos cojuelos, among the most popular costumes in the city. Hundreds of different groups of individuals create their own diablos costumes each year, festooned with mirrors, bells, tiny dolls and beads. The elaborate masks are made of papier- maché. The diablos cojuelos often carry the vejigas or synthetic equivalents, on a string to hit anyone that comes near, and of course, young boys are quick to put the vejigas to use without a need for a costume of any sort*. Other popular personifications in the Dominican Carnaval include Roba la Gallina, usually a man dressed as a very ample, matronly woman with a large bosom and broad skirt to hide her “stolen” chicks—followers (children and youths) who shout “Roba la gallina, palo con ella,” “The hen is stealing, hit her with a stick!” Another personage intrinsic to Carnaval is that of Califé, a poet dressed in black, usually on stilts and with an exaggerated top hat, who uses jocular verse to criticize political figures of the day. Some groups express their African heritage by covering their bodies with black (usually used motor oil). Others called Los Indios dress as Native Americans.

Another popular Carnaval group is the Ali Babas, recalling the story of One Thousand and One Nights. A group of Ali Babas may number in the hundreds, and march to music dominated by double drums. One old theme of Carnaval, most likely originally from Spain, is that of the Bulls and Civilians, typical of the north coastal town of Monte Cristi. Some participants wear animal masks and stage fights with civilians with whips. The cracking of whips in the street also accompanies the fantastic horned masks of the diablos cojuelos of La Vega, just outside of Santiago de los Caballeros in the north central region. Santiago is also known for the brilliantly colored horned masks called Lechones because of their pig-like snouts, and their wearers also wield whips as they ramble through the streets. Variation in these costumes may follow neighborhood efforts to be distinctive. For example, two well-known Santiago neighborhoods—La Joya and Los Pepinos—are distinguished by the form of their horns and so their wearers are called Joyeros (the two main horns covered with smaller horns) and Pepineros (two main horns or many tiny horns ending in flowers).

Scenes from the carnaval—which we’ve chosen here to spell the Spanish way—in the Dominican republic.

On the north coast, the town of Puerto Plata is home to the Taimácaros, groups that recreate the masks and myths of the original Taino inhabitants of Hispaniola, including the rituals of use of tobacco and a hallucinogenic drug called cohoba to invoke the apparition of Yocahú or Opiyelguabiran, among the most important gods of the Taino. In Salcedo and Bonao, enormous horned devil masks called Macaraos (los mascarados, the masked ones) are common Carnaval personages, some representing giants or other mythological beings, and others the Moors of medieval Spain. Other Macaraos dress to resemble African animals such as those seen in early circuses. In the southern town of Cabral, men and women dress asCachuas (the horned ones) with manes of colored paper. The Cachuas also use whips to fight in the streets. These and other themes have been associated with their respective towns for as long as anyone can remember, though at the same time revelers also bring in new costumes and incorporate ideas current in public discourse, like the 4%. Ingenuity in costume design and construction is also apparent. For example, a tradition in the town of Cotuí was to create their costumes from newspaper, hence their name papeluses, with a mask made of a dried calabash fruit (Crescentia cujete, also known ashiguero). Today plastic bags are replacing the newspaper and lending a new look. Sometimes in Cotui the costumes are made of dried plaintain leaf, and are then called platanuses.

Dominican Carnaval shares many elements with the Carnavals of other countries, including neighboring Haiti, but it is also distinctive in the traditions mentioned above, a tiny sample of this truly diverse celebration. From the beginning, Dominican Carnaval was not simply imported from Spain, but rather integrated ideas from many sources, and was always meant to capture the joyous, Caribbean character of the people, happy with life, and always ready to laugh at themselves.

*After being hit once, I discovered that pointing a camera will stop any diabloor boy in their tracks as they will pose and then walk away, but let’s keep this secret among the readers of this magazine.

The information in this article draws on an excellent essay by anthropologist Soraya Aracena, originally published inTR3: Contemporaneidad dominicana—Catalog of the 2005-2006 Traveling Exhibit. I thank Irina Ferreras and our Dominican family for introducing me to the extraordinary celebrations of Carnaval in the Dominican Republic.

Spring 2014, Volume XIII, Number 3

Brian Farrellwill become the Director of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies in July. He is a Professor of Biology and Curator of Entomology in the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard. He travels frequently to the Dominican Republic for research, teaching and pleasure.

Related Articles

Colombian Devils

The devils from Europe and Africa arrived in Colombia and as soon as they encountered the indigenous devils, they happily got together to amuse themselves. They take advantage of any…

Whose Skin Is This, Anyway?

An African-American dresses as a Plains Indian, as if seen through the lens of Fellini, while Andean natives wear white masks and carry whips, pretending to be colonial overseers. Whites…

Making a Difference: A Tale of Two Centuries

Harvard’s ties to Latin America go much farther back in time than 1994, the year that Neil Rudenstine and David Rockefeller launched the David Rockefeller…