Chilean Art

Between Reality and Memory

Edwín Rojas, “Las Princesas.

Chile’s contemporary artists do not cling to any particular ideology. Rather, this new generation of artists seek to understand the recent past without a sense of guilt or victimization. They look to the future with a critical and constructive view, without hatred.

Only a few artists focus on the political and social context. Instead, some vent their criticism on the economic model, the free market and the consumer society. An example is the well-received 1999 exhibition by Bruna Truffa and Rodrigo Cabezas at the National Fine Arts Museum, Si vas para Chile (If you go to Chile), taking its title from a well-known traditional folk song and making fun of consumer culture. Later, the artists produced another exhibition, Si vas para el Mall (If you go to the mall).

While many artists mock the consumer society and the search for easy and quick satisfaction, few concern themselves with the poverty, unemployment, and social and economic inequality that is part of modern Chile. The degree of social consciousness in art in Chile has varied in intensity over time. At the beginning of the last century, the so-called Generación del 13 used painting to highlight social concerns by depicting local customs. An incipient muralist movement in the 1940s, stimulated by the Chilean sojourn of Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, and the 1960s’ “art of denunciation” somehow contributed several artistic ways of interpreting the aftermath of the Pinochet coup (see below).

Yet social concerns have often been on the periphery. In addition to the contemporary mockery of consumerism, much of today’s artistic expression of social concerns deals with lifestyle and identity. The liberation of morés and customs greatly influences artistic production. Topics such as nudity, eroticism and homosexuality are no longer forbidden. There is a resurgence of conceptual art, in which theorical discourse has great relevance. These trends are supported by a great number of art schools that are very keen on new aesthetical expressions. Painting does not escape the conceptualists’ scrutiny; it is often questioned as a means of artistic expression.

At the same time, technological developments have made it possible to incorporate new elements of artistic expression. The use of interactive multimedia has attracted a considerable number of young Chilean artists who explore the possibilities of combining painting, photography, found objects and video in their installations. There is an interweaving of elements and artistic expression. A crisscross of traditional and conceptual changes occurs as a product of a globalized world.

This globalized vision may also account for a number of ecological groups that have recently appeared on the artistic scene. The clay art of Zinnia Ramírez, Ana María Wienecken, Leo Moya and Norma Ramírez reflect the increased use of organic materials as part of this newfound ecological sensibility.

In a sense, this ecological movement is a subtle return to Chile’s artistic past, but with a twist. Chilean art began with landscaping artists who worked in the European tradition with an elitist bent, as Chileans searched for their own identity in the last century. These early landscape artists showed little interest in Chile’s ancestral civilization, reflecting the relative absence of indigenous culture and pre-Columbian past compared to other Latin American countries. This attitude contrasts with some of the new ecological artists that use their art for the vindication of ancient cultures, particularly the Mapuche.

The recycling of discarded materials evokes both ecology and meager resources. The newspaper constructions of Andres Vio are a good example of this trend, creating an intertwining of contemporary art’s uncertainties and forms of expression related to Chile’s living conditions.

Other artists working with a different type of recycled materials have developed a “memory of the past” by searching for lost and found objects. Carlos Montes de Oca, for example, takes his findings out of context and presents them with poetic texts in boxes of impeccable craftsmanship. Some of his latest works have included interventions in urban spaces with small tents which reference the fragility and lack of protection of the human being.

Amid all these changes and experimentation, a very special type of inward-looking Chilean painting still persists, displaying great imagination in alluding to a dream-like world where timeless landscapes are filled with eccentric human figures and illogical objects. Most predominant among these artists are Mario Gómez, Edwín Rojas, and Lorenzo Moya. These artists recoil to a private subjective world, which they splash on the canvass with rich imagination and dexterity.

Despite its diversity, Chilean art is now only beginning to become an integral part of the international and domestic scene. The scarcity evoked by Vio and other recyclers is also an artistic commentary on the difficulty in catapulting contemporary Chilean art into established international circuits due to the lack of resources. Until the 1950s and early 1960s, Chile had been insulated from the international art world.

Within Chile itself, one can see that there is a growing relationship between art and the general public, as attendance to galleries and museums increases. Exhibition spaces—private and public—have increased as well. The opportunity for viewers to permit themselves moments of confrontation and reflection with art has greatly expanded.

However, much of the general public has difficulty understanding the complex theoretical proposals of conceptual art, neither grasping the codes nor possessing the necessary facts. As pointed out by Tomás Andreu, director of the avant-garde art space Galería Animal, some art dealers draw on the seduction of material, shock impact and the surprise element as way of attracting the public’s attention.

Nevertheless, art is becoming an integral part of the urban scene. Large scale sculptures, not only in Santiago but also in Chile’s provinces, bring art to urban spaces. Among the prominent sculptors that have taken part in these projects are Osvaldo Peña, Sergio Castillo, Francisco Gacitúa, Aura Castro, José Vicente Gajardo and Alejandra Ruddoff.

Chilean art may not necessarily incorporate a social message, but the very act of incorporating art into public life is a social statement. Within the overall cultural framework of Chile, successive democratic governments put great effort into elaborating a cultural policy, encompassing all artistic tendencies and expressions. The recently created Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (National Council for the Arts and Culture) has created great optimism within Chile’s cultural community.

Private corporations—in keeping with the current free market economic model—continue to play a major role not only in financing artistic endeavors but in the promotion and diffusion of art. The role of private enterprise in fomenting art began for the most part during the military regime when the dictatorship shied from fostering cultural expression.

During the period of the dictatorship, an art market developed in Chile. New galleries opened up and the public timidly began to acquire contemporary art. The patrons who financed exhibitions and contests were the large corporations of the private sector, looking with favor on those artists who did not overtly politicize their works. Today, Chile’s democratic governments seek a mixed participation between the public and the private sector for all sorts of art, socially conscious or not. Art expressions in today’s Chile are as diverse as the perceptions of every artist vis-à-vis his or her own life experience. Art will be the mirror that will rescue and preserve Chile’s cultural memory.

A QUICK TOUR OF CHILEAN ART HISTORY

1955–1960

-

- The Rectángulo group breaks off with the naturalist model, instead producing rigorous geometric art that never strays away from the primordial role of Chilean landscaping. This generation’s main theorist Ramón Vergara Grez entitles many works in relation to the Chilean landscape.

- Years later, Vergara Grez forms a group called Forma y Espacio. Matilde Pérez, a main figure in the Retángulo group, uses geometric structures inspired by pre-Columbian art.

1961

- The Signo group sees painting as an agent of change. Influenced by the Catalan abstract expressionism movement, members of the group establish a strong relationship with politics and the social issues of the time. Principal artists include José Balmes, Gracia Barrios and Alberto Pérez.

1964–1973

- Street mural painting—with a heavy dose of leftist ideology—appears. Muralist brigades spring forth with energy, including the famous Ramona Parra brigade in which Chilean expatriate Roberto Matta participated. One of the most emblematic places of collective work for these brigades was the banks of the Mapocho river.

SEPTEMBER 11, 1973, AND ON

- The military coup brings brutal repression, torture, exile and censorship. In the first few years of military dictatorship, pessimism and desolation paralyzes the artistic community. Little by little, new ideas, proposals and artistic creativity reappears, mirroring the historical context of the country. Some of these artistic expressions have been referred to asestetica de la expiación, emerging as a conscience of a sort of a collective guilt for the loss of democratic values. Still other expressions rise from the ashes—la estetica del escombro, born out of pondering on the devastated democratic scenario (Milan Ivelic in “Arte Latinoamericano del siglo XX”, Editorial Nerea, 1996, p.309).

1975–1982

- A new iconography appears in the Chilean art scene. The traumatic experience suffered by artist Guillermo Núñez at his exhibition at the Chilean-French Cultural Institute is a case in point. Núñez’s installation consisted of various bird cages individually filled with diverse objects such as bread, flowers and a Chilean flag. After the opening day, the artist was detained by the police, subjected to six months of imprisonment, partially blindfolded and eventually released into exile.

- Local artists had to develop strategies to elude censure. The social message of their work became hidden through the use of artistic metaphors and indirect language. Many artists felt that the traditional way of expressing their art such as painting, sculpture and prints insufficiently expressed what they felt and created new avenues in relation to materials, social reality, and politics of the times. Documentary photography and other new material became frequently used to express social reality. In tandem with the international trend, this subversion of traditional means of artistic expression gave way to a conceptual art experimentation such as installations, art auctions and body art.

- CADA (Colectivo Acciones de Arte), an interdisciplinary group of visual artists and intellectuals, utilized urban space to create new circuits for the flow of art. Main figures were: Lotty Rosenfeld, Juan Castillo, Raúl Zurita, Diamela Eltit and Fernando Balcells.

- The so-called Escena de Avanzada, composed of artists such as Eugenio Dittborn, Carlos Altamirano, Juan Dávila, Francisco Smythe, Gonzalo Mezza, Carlos Leppe and Gonzalo Díaz, ponder over what is to be a painter in Chile. TheEscena de Avanzada, a term coined by the art critic Nelly Richard (Richard, “Margins and Institutions: Art in Chile since 1973” Art & Text, Melbourne, 1986) point through their theoretical discourse to changes in the codes of cultural communication.

- Dittborn acknowledges the precarious conditions of the country and plays around with it. He underscores the marginality of Chile in different aspects including the international art circuit. Dittborn sends his works through the mail in neatly folded packages.

- Juan Dávila uses forms of Pop art with great irreverence and Carlos Leppe injures his own body to project his art.

1980S

- In 1981, the first French-Chilean meet of video art occurs. In this gathering we found the works of Juan Downey and Alfredo Jaar. In opposition to the French video artists, who place great emphasis on the technology, these Chilean artists are more interested in the link between content and technology. A neo-expressionist trend emerges, influencing mostly younger artists fresh out of art schools like Bororo, Samy Benmayor, and Omar Gatica. Their work, a sort of action painting with open-minded ideas and technique, is perceived as an act of liberation against repression although no theoretical underpinning supports this body of work. It is impetuous and spontaneous with some influence by the Italian Transvanguardia movement.

- Another group of artists, sculptors and painters base their work on a personal vision that originates in the inner soul of the artist, where fantasy’s flight plays a fundamental role. Principal figures include Mario Toral, Rodolfo Opazo and Gonzalo Cienfuegos.

- With the onset of the economic crisis of 1983, censorship became weaker. An important group of exiled artists return, including José Balmes, who spearheaded a more politicized and testimonial art. Street mural painting appears in the shantytowns, suburbs and closed spaces. In 1988, the government called for a plebiscite, and the muralist brigades became visible again in support of “No” vote to decide whether the military regime should continue in power.

1990

- With the inauguration of a new democratic government, the art scene changed. Young artists who did not live in a dictatorial regime took charge of the memories of their parents. The awareness of human rights violations is a recurring theme for some. Because of the recent 30th anniversary of the military coup, the mass media revisited the history of the dictatorship, helping to relive or narrate the process with more maturity.

Arte Chileno

Entre realidad y memoria

Por Beatriz Huidobro Hott

La contingencia histórica ha sido un importante referente de las artes visuales chilenas a partir de la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Nos encontramos ante una diversidad de tendencias, de caminos paralelos, de entrecruces y transferencias.

La búsqueda de lo propio se inicia históricamente a través del paisaje. La carencia de un pasado precolombino y la falta de interés por los vestigios, aunque escasos, de las etnias originarias y el desconocimiento de la riqueza cultural de su percepción del mundo, privilegiaron un arte con una fuerte influencia europea, y de un marcado carácter elitista.

La excepción nos la entrega la llamada Generación del 13, quien a comienzos de siglo realizó una pintura costumbrista, vinculada a demandas sociales, que tuvo eco en la literatura y en la música nacional. No debemos olvidar un incipiente movimiento muralista que surgió en los años cuarenta, motivado especialmente por la estadía de David Alfaro Siqueiros en Chile.

Existía un desfase con relación a los movimientos de los centros artísticos internacionales. Esta situación se revierte en la década de los cincuenta e inicios de los sesenta. Se acortaron las distancias e hicieron su aparición tendencias de arte no figurativo. En 1955 el grupo Rectángulo, con un arte geométrico riguroso, rompió con el modelo naturalista. Se produjo una confrontación con el esquema anterior, pero no se desligó de la referencia a la visión del paisaje chileno. Ramón Vergara Grez, su principal representante y teórico, lo alude en los títulos de sus obras.

Esta agrupación deriva años más tarde, en Forma y Espacio en la que participará Matilde Pérez, interesada en las estructuras geométricas del arte precolombino. Realiza un arte cinético que no es comprendido, señalando la artista: “quedé encerrada entre cordillera y mar sin encontrar ningún eco”, actualmente, para varios artistas jóvenes, su obra es un referente.

En 1961 surge el grupo Signo, cuyos integrantes se vinculan a las corrientes informalistas, especialmente al arte catalán. Participan José Balmes, Gracia Barrios, Alberto Pérez y Eduardo Martínez Bonatti. Estos jóvenes se cuestionaron acerca de la pintura como agente de cambio. Establecieron una relación con la política y los acontecimientos sociales contingentes.

En los años sesenta la ideologización del país se acelera. Las grandes fuerzas quedan definidas claramente. Se suceden gobiernos de distintas tendencias políticas en una misma década. Se acaba el diálogo lo que lleva a serias confrontaciones. Es un periodo de importantes transformaciones sociales y políticas y a la vez se produce la fragmentación de la sociedad chilena al polarizarse las tendencias.

Los artistas participan activamente de este proceso, se genera un arte de denuncia, que se visualiza claramente en su iconografía. Entre 1964 y 1973 hace su aparición la pintura mural callejera, que se nutre de los planteamientos políticos de izquierda. Surgen las brigadas muralistas, como “Ramona Parra”, en la que participó Roberto Matta en uno de sus viajes a Chile. Uno de los lugares más emblemáticos donde realizaban este trabajo colectivo, es la rivera del río Mapocho.

A partir de 1973 se vive una situación nueva y traumática. El 11 de septiembre el Golpe Militar trae consigo una brutal represión con torturas, exilio y censura. En los primeros años el pesimismo y la desolación paraliza la labor de los artistas. Poco a poco reaparecen planteamientos vinculados con la situación histórica, “una de ellas, que podríamos denominarestética de la expiación, surgió de una conciencia de culpa colectiva por la pérdida de los valores democráticos; otra, que llamaremos estética del escombro, nació de las reflexiones y juicios que provocaba la contemplación del espacio democrático arrasado”.

Hacia 1975 hace su aparición una nueva iconografía en el arte chileno. La situación vivida queda claramente graficada en lo sucedido con la exposición del artista Guillermo Núñez realizada en el Instituto Chileno-Francés de Cultura, donde presentó un conjunto de jaulas para pájaros y dentro de ellas colocó diversos objetos, como un pan, una flor o una banderita chilena. Al día siguiente de la inauguración fue detenido por la policía. Durante seis meses estuvo en distintas prisiones, un gran tiempo con los ojos vendados, hasta que le fue posible exiliarse.

Desde entonces los artistas debieron revisar sus estrategias de trabajo para eludir la censura. Los contenidos de mensaje social fueron velados. Hicieron uso de la metáfora plástica, de un lenguaje indirecto.

Muchos creadores sintieron que los medios de expresión tradicionales, como la pintura, el grabado y la escultura, no eran suficientes para poder expresar lo que sentían, e inventan nuevos recursos, buscan una relación entre los materiales y la realidad social y política que están viviendo. La fotografía testimonial será profusamente utilizada. Esta subersión de los medios tradicionales se inserta en una tendencia mundial de experimentación conceptual. Aparecen las instalaciones, las acciones de arte, el arte corporal. Estas manifestaciones serán testimonio de aquello que no se podía decir a través de otros medios de comunicación.

Surge el grupo CADA (Colectivo Acciones de Arte) que utilizó el espacio urbano, creando así nuevos circuitos de circulación del arte. Era un grupo interdisciplinario donde participan artistas visuales e intelectuales, fueron los propios artistas los teóricos de sus obras, entre ellos Lotty Rosenfeld, Juan Castillo, Raúl Zurita, Diamela Eltit, y Fernando Balcells.

Artistas como Eugenio Dittborn, Carlos Altamirano, y Gonzalo Díaz, se plantean qué es ser pintor en Chile. Dittborn acepta la precariedad y trabaja con ella. Hace notar la marginalidad de Chile en diferentes aspectos incluyendo el circuito internacional artístico. Envía por correo sus obras en papel doblado.

Estos artistas cuyo quehacer se realiza entre 1977 y 1982 constituyen La Escena de Avanzada, denominado así por la crítica de arte Nelly Richard, con un discurso teórico que modifica los códigos de comunicación cultural. Juan Dávila haciendo uso de formas del pop art con gran irreverencia, y Carlos Leppe, hiriendo su propio cuerpo, se insertan también como figuras destacadas en este conglomerado.

En los ochenta surge una tendencia neoexpresionista, sobre todo en los pintores más jóvenes recién egresados de las escuelas de arte, como Samy Benmayor, Bororo y Omar Gatica. En su pintura gestual y desenfadada, se percibe un acto de liberación de las represiones. No hay un aporte teórico que sustente esta pintura. Es impetuosa y espontánea. El conocimiento de la Transvanguardia italiana no es ajena a estas tendencias subjetivistas.

Se desarrolla un mercado del arte en Chile, surgieron nuevas galerías y muy tímidamente el público comenzó a adquirir arte contemporáneo. Los mecenas, quienes financiaban los concursos y exposiciones, eran las empresas del sector privado, a las que les favorecía la carencia de un contenido político crítico.

Subsistió otro sector de artistas que no dejó de pintar y esculpir con propuestas paralelas al arte conceptual durante todo este periodo. Este tipo de pintura descansa en un imaginario personal que surge de la interioridad del artista (Mario Toral, Rodolfo Opazo, Gonzalo Cienfuegos), donde la fantasía juega un rol fundamental.

A partir de la crisis económica de 1983, la censura se va debilitando. Comienza a regresar un grupo importante de pintores exiliados, como José Balmes, quienes realizan un arte de carácter testimonial. Reaparece el muralismo en las poblaciones de la periferia urbana o en recintos cerrados. En 1988 salen las brigadas nuevamente a la calle para apoyar el No en el plebiscito convocado por el gobierno militar.

En 1990 el retorno de la democracia trae consigo un nuevo escenario. Jóvenes que no vivieron la dictadura militar se apropian de la memoria de sus padres. Un mundo, desconocido para muchos, queda en evidencia. El reconocimiento de la violación de los Derechos Humanos será para algunos, un tema recurrente. Se han hecho recientes revisiones a través de los diferentes medios de comunicación con motivo de cumplirse 30 años del golpe militar, lo que lleva a asumir con madurez el proceso vivido o relatado.

La joven generación no participa de una ideología. Quieren comprender el pasado reciente, sin el sentido de culpa o de víctima de la generación anterior. No insistir en los rencores y mirar hacia el futuro, con una mirada crítica, pero constructiva.

Las posturas van dirigidas en otro sentido. Son pocos los artistas que abordan la problemática política y social. Surge una expresión crítica al modelo económico, al libre mercado, a la sociedad de consumo. La más emblemática es la exposición de Bruna Truffa y Rodrigo Cabezas que presentaron en 1999, en el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes y que denominaron “Si vas para Chile”, aludiendo al título de una conocida canción popular. Más tarde realizan otra muestra titulada “Si vas para el Mall”.

Se ironiza acerca de la sociedad de consumo, de la búsqueda de un placer fácil y superficial. Pero no se ve reflejada una preocupación por la pobreza, por el desempleo o por la desigualdad social y económica, que aqueja al Chile actual.

Surgen grupos ecologistas, como también la reivindicación de un pasado acerca a algunos artistas a las etnias autóctonas, especialmente la mapuche. La utilización de materiales orgánicos, toman relevancia, como los trabajos realizados en barro, es el caso de Zinnia Ramírez, Ana María Wienecken, Leo Moya, y Norma Ramírez.

Otros artistas rescatan la memoria a través de objetos encontrados, como Carlos Montes de Oca, quien los descontextualiza presentándolos, junto a textos poéticos, en cajas de impecable factura. Actualmente ha realizado intervenciones en el espacio urbano con pequeñas carpas que hacen referencia a la desprotección y fragilidad del ser humano.

La liberación de las costumbres también ha influido en las propuestas artísticas. Hay una mayor tolerancia hacia temas antes vedados como los desnudos, el erotismo o la homosexualidad. Resurge el arte conceptual, donde el discurso teórico es de gran relevancia. Esta tendencia es propiciada por un gran número de Escuelas de Arte. Están muy atentos a las nuevas propuestas estéticas. La pintura no es ajena a este análisis, hay un cuestionamiento al soporte bidimensional.

El desarrollo tecnológico ha hecho posible incorporar nuevos medios. La utilización de la interacción multimedia ha atraído a un número importante jóvenes, que conjugan pintura, fotografia, objetos encontrados y videos en sus instalaciones. Se entrecruzan las fronteras de los medios y lenguajes artísticos. Se producen cruces y desplazamientos formales y conceptuales, propios de un mundo globalizado.

Destaca el uso de materiales de desecho que son reciclados, como las construcciones con papel de periódico de Andrés Vio. Son materiales cotidianos, sobrantes, que remiten a la precariedad, a la creatividad popular ante la falta de recursos. Se enlazan problemáticas propias del arte contemporáneo y un lenguaje atinente a las condiciones de vida de nuestro país. También esta precariedad alude a la dificultad de dar a conocer el arte chileno en los circuitos internacionales establecidos.

En la actualidad podemos concluir que se acrecienta la relación entre el arte y el público, el que asiste a museos y galerías. Han aumentado los espacios de exhibición, tanto privados como estatales, lo que permite que se creen instancias de confrontación y de reflexión.

El problema se suscita con las propuestas teóricas muy herméticas ya que el público no posee los códigos que hacen posible la comprensión de estas obras. Algunos galeristas apuestan porque la seducción de los materiales, el impacto o la sorpresa actúen como los caminos de acercamiento y de atención.

Paralelamente persiste la pintura, especialmente aquella con un imaginario que alude a un mundo onírico, paisajes donde se insertan extrañas figuras humanas y objetos incongruentes con un dejo de atemporalidad. Es el caso de la obra de Mario Gómez, Edwin Rojas y Lorenzo Moya. Se repliegan en un mundo privado, subjetivo, el que transfieren con una rica imaginación y gran oficio.

Con el deseo y la voluntad de los gobiernos democráticos se ha trabajado para elaborar una política cultural, que acoja las diversas tendencias y manifestaciones, dando lugar al recientemente creado Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, lo que conlleva a un mayor optimismo. También es necesario destacar el interés por presentar el arte en los espacios públicos; el emplazamiento de esculturas en el entorno urbano, no solo en Santiago, sino a lo largo del país, ha sido muy acertado. Entre los artistas que han participado en estos proyectos se encuentran los destacados escultores Osvaldo Peña, Sergio Castillo, Francisco Gacitúa, Alejandra Ruddoff, José Vicente Gajardo, y Aura Castro.

De acuerdo al modelo económico, las empresas privadas continúan ejerciendo un rol fundamental en el financiamiento de los proyectos artísticos, en su difusión y promoción, rol que asumieron en el período de la dictadura, puesto que el gobierno militar se desligó de las responsabilidades relacionadas con las manifestaciones culturales. Actualmente se han buscado mecanismos de participación de manera conjunta.

Podemos apreciar que el arte pone en evidencia una realidad compleja, contradictoria, de la que no siempre estamos conscientes. Las manifestaciones son tan diversas como lo son las percepciones que cada artista sensible tiene frente al entorno que le tocó vivir. El arte será el espejo que rescate y preserve nuestra memoria cultural.

Spring 2004, Volume III, Number 3

Beatriz Huidobro Hott is an art historian and curator in Santiago.

Beatriz Huidobro Hott es historiadora del arte y curadora en Santiago.

Related Articles

The Other 9/11

Like a bolt of lightning that illuminates a darkened landscape, attracting everyone’s attention, the recent commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the military coup of 9-11-1973 has…

Open Schools, Open Minds, Open Societies

Seventeen years of authoritarian rule leave deep scars in the people of a nation. They also leave deep marks in an education system. On a trip to Chile in June 2003 to study the effects of…

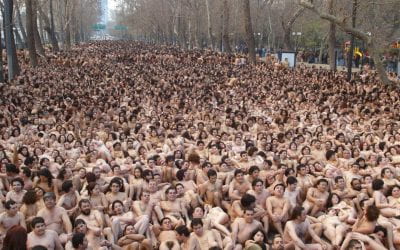

Naked in Santiago

On a freezing winter Sunday morning in July 2002, four thousand people euphorically took off their clothes in a downtown Santiago park. Spencer Tunick, the American photographer working…