Constructing Democratic Governance in Latin America

A REVIEW BY ALFREDO CORCHADO

Democracies are messy—none so more than those across Latin America. A common refrain used by academics and journalists alike to describe those democracies is usually “weak,” or “fledgling.”

And yet, in spite of endemic poverty, weak economies, rising security concerns and growing drug violence, democracy continues to take root across the continent, albeit with a few hiccups here and there. This is the thesis of the third edition ofConstructing Democratic Governance in Latin America, a 412-page tome edited by Jorge I. Domínguez, a professor and Vice Provost for International Affairs at Harvard University and Michael Shifter, Vice President for policy of The Inter-American Dialogue and an adjunct professor at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. The book features chapters written by thirteen experts on the region.

Even under the glare of media scrutiny and the criticisms of some skeptical analysts and constituents alike, democracy in Latin America is proving to be a “resounding success,” according to Shifter. “The advance may not be irreversible,” he notes in his chapter. “But it is becoming increasingly ingrained, and voting, happily, is a tough habit to break.”

Still, economic problems, security issues and old paternalistic practices continue to challenge these incipient democracies, threatening the very advances that people fought for decades to achieve, often at the cost of their own lives.

In Venezuela, President Hugo Chávez continues to amend the constitution to assure his power for years to come. In Colombia, President Álvaro Uribe is accused of thinking about doing the same. And in Argentina, economic calamity threatens new generations and a democracy with a weak congress, and fragile state institutions. The president remains too powerful, thus hampering the checks and balances that any democracy needs to fully take root, notes Steven Levitsky, a professor of government and social studies at Harvard University, in his chapter on Argentina.

But “no government across Latin America today is killing voters, or stealing elections, or using coups to take power,” Levitsky said in an interview. “It’s difficult to sustain democracy with high levels of poverty so the fact that democracy works even at a minimal sense represents a major achievement for Latin America.”

Levitsky and other experts, however, warned that Latin American governments must do more to tackle poverty and provide security for its citizens, or risk seeing democratic institutions weakening and populist leaders rising. “Economic crisis and security concerns are the prime killers of a democracy,” he said.

Consider the drug violence across Mexico, a nation of 110 million people that shares a 2,000-mile border with the United States. Nine years after the opposition National Action Party, or PAN, defeated the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, ending 71 years of one-party rule, the verdict is still out. The PAN was supposed to solidify democracy, which had been little more than a word among Mexicans during several decades of oligarchic rule until that point. Today, the rule of law in Mexico is withering even before it takes root. Since 2006 more than 10,000 people have been killed in drug-related violence.

The government’s inability to restore order and retake regions of the country from drug traffickers has some growing nostalgic for the semi-authoritarian PRI. The PRI, after all, ruled with an iron fist. Its corrupt governance provided the glue that kept society together, as it protected citizens by coddling criminals in exchange for hefty kickbacks. Often, PRI government officials made arrangements with members of organized crime in exchange for lucrative kickbacks. The pacts guaranteed that deadly disputes were taken care off internally, unlike today when powerful weapons and decapitations terrorize entire communities.

Almost overnight, Mexico’s “Imperial Presidency” lost its power and transferred quickly to some members of Congress determined to hold on to as many past paternalistic practices as possible. The result: stagnation that has made governing Mexico more difficult by stalling pivotal reforms, as Denise Dresser, a professor of political science at the Autonomous Technological Institute in Mexico City, notes in her chapter. “So what the presidency has given up, or been forced to concede, Congress has gained,” she writes. “ …. Drug traffickers and organized crime have taken advantage of what the Mexican state is no longer able to ensure – such as a monopoly on violence.”

And yet Levitsky argues, “Being there in Mexico and reading the newspapers everyday makes you convince that Mexico doesn’t look good … but Mexico’s long term trajectory is very good.” He added that Mexico is on par with Costa Rica, Uruguay, Chile and Brazil as nations that have emerged, or are emerging, as “serious democracies.”

Nonetheless, Domínguez strikes an ominous note in his chapter when he warns of the generally poor “record of Latin American democratic performance.” “The key to democracy remains the decision of its citizens,” Domínguez stated. “In their hands and on their wisdom, rest the region’s democratic prospects. As the region approaches the 200 anniversary of the start of its independence, Latin America’s democratic star shines less brightly than it did a decade ago, but it still shines more brightly than it did for the proceeding generation.”

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Alfredo Corchado is a 2009 Nieman Fellow at Harvard University and Mexico Bureau Chief for The Dallas Morning News.

Related Articles

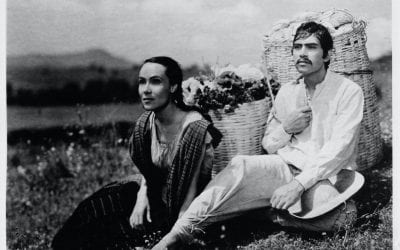

Golden-Epoch Cinema in Mexico

The acting was appalling, the inconsistencies of plot and character so constant that any occasional consistency seemed glaring. The soft-bodied chorus girls always skipped and wiggled in non-unison and the heroines always sobbed in precisely the same cadence, and no director…

First Take: New Technologies and New Narratives

Recent film trends in Latin America and beyond cannot be understood without examining new technologies and their impact on new narrative forms. That is why, in November 2008, the Real Colegio Complutense of Harvard University, together with the Universidad Complutense…

First Take: Film in Latin America

Latin America cinema has undergone a remarkable transformation since the mid-1990s, with Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba and Mexico in particular emerging as vibrant centers for some of the most innovative and imaginative filmmaking in contemporary world cinema. A bastion…