Corporate Philanthropy

Is it the government or the philanthropist that should lead the way in combating poverty? It’s an old debate, with special relevance for today’s Latin America. In his Memoir on Pauperism (1835), Alex de Tocqueville opposed “legal charity” because any measure that establishes legal charity on a permanent basis and gives it an administrative form thereby creates an idle and lazy class, living at the expense of the industrial and working class. On the contrary, individual alms-giving established valuable ties between the rich and the poor. The deed itself involves the giver in the fate of the one whose poverty he has undertaken to alleviate.

Industrialized countries had to wait until the 20th century to solve this controversy in favor of the welfare state. In the developing world, however, a plethora of government and private arrangements are still in place. Wealthy entrepreneurs, community organizations, trade unions, churches and especially women contribute to ameliorate the situation of the poor. I don’t intend to place a value on the merits of these arrangements; that history is not yet written. Instead, I will concentrate on the case of Colombia.

Colombia’s corporate philanthropy is one of the oldest and strongest traditions in Latin America, taking into account the size of economic contribution, its diversity and innovative capacity. In 1997 there were 94 corporate foundations with assets nearing one billion dollars, 1% of Colombian GDP and 5% of total public expenditures. However, a high proportion of resources concentrated in the largest foundations. The 10 largest foundations account for 97.7% of the total assets of all foundations in Colombia. This situation raises the question of how these few powerful foundations compare to other non-government organizations or membership associations with fewer resources. It also raises the question of the empowerment of the private sector to which these foundations are linked in a country with high levels of concentration of capital: in Colombia the four largest companies in each sector concentrated 62% of production and more than 67% of income (World Bank, Colombia: Private Sector Assessment, 1994).

Another reason for examining the Colombian case is the historical precariousness of the state measured by its weak presence in the territory and its difficulty in mediating the interest of powerful actors. Private sector support for social programs can be understood as a reaction to the lack of presence of the state. It is also a reflection of the saying there is no healthy business in a sick society, an imperative to better the social environment where business is conducted. The state has increased the contracting of social services with foundations and non government organizations. I contend that while contracts with corporate philanthropy increases economic resources and provides innovative solutions to social ills, it has not similarly contributed to the democratization of the decision making process nor to the strengthening of the legitimacy of the state. Programs in the hands of foundations are not accountable to citizens nor do they increase the capacity of the state to act as an intermediary of powerful interests. I examine this problematic using the most successful experience of private philanthropy: the micro-credit program. Although it is a worrying situation, I believe it is one that has a solution.

The National Plan of Microenterprise Development (NPMD)

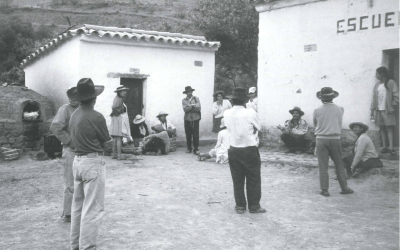

The 1980s economic crisis made evident the vulnerability of the development process. Both government and private sector circles regarded poverty, unemployment and informal sector growth with concern. It’s not surprising that the Carvajal Foundation, which had worked with micro-entrepreneurs since 1976, lobbied the national government to launch the National Plan of Microenterprise Development in 1984. The NPMD co-finances training, support centers for microentrepreneurs’ credit and marketing activities. The NPMD launched a private corporation, the Corporación Mixta para el Desarrollo de la Microempresa to strengthen these projects and distribute economic resources. The private sector, especially corporate foundations, carried out the plan for the most part. Colombia thus found itself at the vanguard of countries in the region. When approved the NPMD had US$ 7 million of Inter American Development Bank-IADB financing and US$ 3 million from national resources. In 1990 these resources doubled. Presently, there are two million small enterprises, which contribute 25% of GDP.

The NPMD gave corporate foundations leverage in terms of its financial resources, since the government co-financed 50% of its projects. The plan also gave foundations more decision making power by allowing them to influence the orientation and distribution of economic resources. With half of the seats on the Corporación Mixta board of directors where the policy for the sector is developed, foundations are over represented in the NPMD’s decision-making and policy boards. Foundations are also members of the Asociación Nacional de Fundaciones Microempresarias, a non-profit organization, which is an active member of the board of directors of the Corporación Mixta. There is also an over-representation in the board of directors of the Association where the largest foundations have five of the seven seats.

Foundations also had half the votes in the Technical Awarding Committee where resources are allocated. Furthermore, the institutions participating in the board of directors are allowed to implement projects financed by the Corporation. In 1998, from the total amount of resources assigned by the Corporación Mixta, foundation members of the Asociación received 60% of the resources approved. Seven of the largest foundations received 25% of the yearly resources. This tremendous concentration of power explains but does not justify their resistance to the creation of an organization of micro entrepreneurs that participate at the same level than the Asociación. As one study concludes, political empowerment was not a priority in the agenda of corporate foundations in their work with micro-entrepreneurs (Rodrigo Villar, La Influencia de las ONG en la Política para las Microempresas en Colombia, unpublished, 1999).

Without a doubt, foundations reach an important segment of the small proprietors in Colombia and they contribute with important resources. Twenty corporate foundations have micro-enterprise development as their main activity and most foundations have programs for small entrepreneurs as part of their activities. The program has been able to combine the liberal principles of self-responsibility and creation of wealth while increasing the ties between the company, the poor and society in general. As a result, private philanthropy is gaining important social recognition. The December 3, 2001, issue of the important Colombian magazine Semana dedicated an entire section to social responsibility. The publication mentions the case of Fundacion Santodomingo, which granted a quarter million credits worth US$28 million in the past 20 years; Fundación Compartir had trained 103,000 micro entrepreneurs and Fundación Corona did the same for another 32,000. Being identified as a company with noble causes or altruistic activities provides significant benefit to a company in terms of image vis-à-vis consumers. Dinero magazine undertook a survey of 301 Colombian businesspersons (August 1998) and the firms that garnered the most admiration were those that maintained foundations. The three highest ranked were Bavaria, Carvajal and Exito, all of which maintain their respective philanthropic company. This admiration contrasts with recent polls of public perception of trust, where private companies outrank government and political parties: on an index of 10, the evaluation is 4.98 for larger companies; 3.9 for the national government and 2.77 for political parties. The latter’s rank is higher only than that of guerrilla and paramilitary groups. (John Sudarsky, Colombia’s Social Capital, unpublished)

Far from attributing the de-legitimization of the state to the private sector, I ask how much the state is missing the opportunity for building a public discourse that allows it to recover its fragile political legitimacy, especially when an important part of this legitimacy derives from social programs. This does not mean to suggest stopping government support to corporate foundations. Legitimacy is not a zero sum relationship. The solution is to find mechanisms that acknowledge the presence and contribution of the state to these programs. For example, not all corporate foundations’ financial balance sheets are available for public scrutiny. In those cases where they are available, these balance sheets do not discriminate between the sources of funds nor their destinations. On rare occasions beneficiaries are informed of public support for these programs. Reporting about the nature of the funds would make foundations more accountable to citizens in their quality of administrators of public and not just private funds.

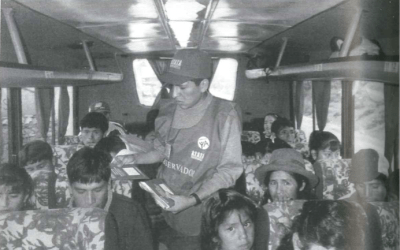

A similar consideration can be applied to the methodologies guiding the relationship between providers and beneficiaries of the program. Most of the foundations adopted the methodology developed by Carvajal foundation: three weeks of training courses in accounting, investment and management as a requisite to obtain credit. This methodology has been questioned because it tends to select the beneficiaries more likely to remain in the program, such as those with higher income.

Some foundations build donor-beneficiary relationships in a paternalist and affective way, while others are more participatory. An example of the latter is Fundación Social’s program Integral Local Development, whose objective is the consolidation of the poor as social subjects. The methodology includes a political dimension allowing the beneficiaries to negotiate their projects. However, the methodology used by most foundations is assistentialist to ensure the loyalty of the beneficiaries. Some programs are overloaded with experts ranging from economists, accountants, psychologists and social workers in charge of evaluating the economic and social aspects of the beneficiaries like living conditions, family conditions, how they live and what are the condition of the house.

Following Tocqueville’s dictum on private giving, the deed involves the giver in the fate of the one whose poverty he has undertaken to alleviate. What he missed is that it is not always in the interest of the giver to develop in the beneficiary the capacity to negotiate the poor’s collective interest. This transformation is better negotiated when beneficiaries are participants of a public service where government and private sector participate. A solution is for government to provide standards for selection of beneficiaries and instances of negotiation based on rights rather than affects.

Last but not least in importance is the issue of evaluation and monitoring of the NPMD. Three partners conducted a recent evaluation: Departamento Nacional de Planeación, Fundación Corona, Corporación para el Desarrollo de las Microempresas, (Evaluación de los Programas de Apoyo a la Microempresa, 1997-1998, 1998). The study was conducted under the leadership of Fundación Corona, a highly specialized, technical and perhaps the leading corporate foundation in terms of quality of interventions and capacity for innovation. According to the study the program did not generate employment nor pull out people from poverty. The program helps beneficiaries to remain in their position. The study found that this was more true for the poorest and women. The most successful cases occurred in educated men with a higher socio-economic level. According to the study the best solution is a separation of those with potential from those that need income. In their view employment generation and wealth, on the one hand, and the support of the poorest, on the other, are two objectives that can not be dealt with the same instruments. The latest Development Plan (1998-2002) reflected this solution, calling for providing a differential attention for micro enterprise with potential for development and micro enterprise for generation of income. Without evaluating the impact of the proposed solution, I want to call attention to the fact that this is a political decision where beneficiaries have a stake. Without questioning the professionalism of the study it is worrying that foundations are acting in all the instances of the NPDM: design, allocation of funds and evaluation. Beneficiaries are absent.

This explains my call to democratize the process of decision-making, accountability and legitimacy of the collaboration between the state and corporate philanthropy in Colombia.

Spring 2002, Volume I, Number 3

Cristina Rojas teaches international political economy at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs. A 1999-2000 DRCLAS Visiting Scholar, her research on philanthropy was also financed by a grant from the Ford Foundation. She is the author of Civilization and Violence: Regimes of Representation in Nineteenth Century Colombia (University of Minnesota Press, 2002). The book is published in Spanish by Editorial Norma.

Related Articles

Social Responsibility in Latin America

Effective involvement in social issues is essential to business, both in the United States and Latin America. In recent years, most-although certainly not everyone-increasingly agree that business …

Brazil’s Comunidade Solidária

In a dynamic, complex and unequal society such as Brazil, processes of change may take a while to mature but once unleashed they tend to move forward at an accelerated pace….

Andean Traditions of Giving

In Andean tales, the fox is always the central figure, a hero who is never wins, but who is also never defeated either. His comings and goings stretch from mythical times to colonial history …