Cuba’s Many Faces

Not Quite the New Millennium

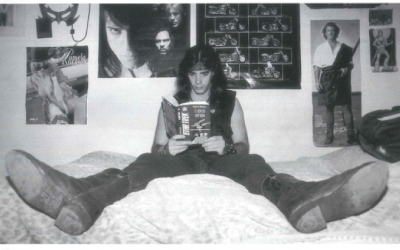

Reading Granma to workers in a tobacco factory.

Surely Elián González was Cuba’s most public face as the decade reached its end. The little boy’s mother took Elián aboard a boat that capsized in the Straits of Florida; the mother drowned. Just shy of six years of age at the time of his rescue in the high seas, the boy’s extended-family relatives in Miami sought to keep him. The boy’s father in Cuba reclaimed him. The U.S. government dithered for weeks before making the decision that the boy should be returned to his father. In the meantime, President Fidel Castro launched a massive campaign throughout Cuba to seek public support for Elián’s return. No doubt President Castro believed that this little boy should be in Cuba. No doubt, too, this unexpected crisis was a win-win situation for him, no matter how the crisis would end. If the boy were to be returned, it would be a success for him; and if the United States were to prevent the boy’s return, it would reveal the U.S. government as an accomplice to a kidnapping. More than two million people marched in the streets in various parts of Cuba; every public meeting, no matter how local or how lowly, was also expected to endorse Elián’s return.

Other public faces of Cuba were those of its chief economic ministers, José Luis Rodríguez, Minister of the Economy, and Manuel Millares, Finance Minister. In December 1999, they reported that Cuba’s gross domestic product would grow by 6.2 percent that year, the second highest growth rate for any year in the 1990s, and only the second year of the decade with significant growth. They beamed with pride on national television. The economic results allowed them to declare victory over the U.S. Helms-Burton Act, enacted in 1996 to toughen the U.S. embargo and related economic sanctions on Cuba. Cuba’s economy had suffered, they made clear, but Cuban leaders and workers had joined hands in yet another successful instance of resistance to yet one more attempt by the United States to overturn the political regime founded in 1959.

Ministers Rodríguez and Millares, as is their custom, emphasized the statistical aspects of this impressive accomplishment. Their numbers reveal the dimensions of an economic recovery in 1999, even if it falls still far short of returning to Cuba’s level of gross domestic product in 1989. Cuba’s workers had become appreciably more efficient, albeit from a very low starting point. Cuba hosted more than 1.6 million tourists from many countries throughout the world, confirming the tourist industry as the engine of economic recovery. Cuba’s budget deficit as a percentage of gross domestic product held at 2.4 percent (it had been about 33 percent in 1993), fairly consistent with its level for the second half of the 1990s. Cuba’s sugar economy recovered a bit in 1999 from the disastrous production levels to which it had fallen. At not quite 3.8 million metric tons, however, the 1999 sugar harvest accomplishment was still below the 1963 harvest, the worst sugar harvest since revolutionary victory in 1959 until the collapse of sugar output in 1998. Cuban output of petroleum, manufacturing, and various non-sugar agricultural products improved substantially in 1999. Cuban enterprises were also performing much better; many fewer state firms were money-losers. And yet, even at the end of the happy year of 1999, about one quarter of Cuba’s state enterprises still ran deficits. Finally, over one million Cuban workers were paid to some extent in hard currencies (U.S. dollars or equivalent currencies); nearly two-thirds of all Cubans had access to hard currencies, although most had only modest amounts. Nonetheless, life was austere for the significant minority of Cubans without access to hard currency. Cuba’s median salary rose in 1999 to 223 pesos per month, which amounted to about $11 dollars at the prevailing exchange rate.

Cuba displayed as well the successful faces of its new internationally competitive business enterprises. Habalear S.A., a joint venture between Canada’s International Clothing Inc. and a state enterprise owned by the Cuban Ministry of Light Industry, began to produce high-fashion shoes for the international market, including tourist dollar-currency stores in Cuba. Its 40 workers were expected to produce about 120 of these pairs of shoes per hour. Ordinary Cubans would not be its most likely customers, however. Cubacel, another joint venture, offers cellular telephone services in Cuba. For four consecutive years, its 104 workers have won the “Vanguardia Nacional” recognition for best overall efficient production. In 1999, the firm’s profit rate exceeded 35 percent. The firm was not well known to ordinary Cubans, however, because it sells only to business firms, not to individuals. The faces of successful entrepreneurship in Cuba, therefore, reveal as well the faces of the nation’s new inequality.

Equally visible as the 1990s closed were Cuba’s internationalist health-care workers, the Cuban government’s sole far-reaching internationalist program as the century approached its end. They were the face of Cuba’s success at home in constructing an impressive health-care system for its people; they were also the face of Cuba’s once far-flung attempt to project its influence worldwide. Cuba’s special niche was the rapid deployment of health personnel to assist with natural disasters. Cubans were thus sent to Central America to assist with the care of the sick and wounded in the aftermath of Hurricane Mitch; in late 1999, for that and related purposes there were still 434 Cuban medical doctors in Guatemala, 87 in Nicaragua, 53 in Belize, and 31 in Honduras. In December 1999, terrible flooding and mud slides devastated a large area of Venezuela, displacing a great many people. Cuba immediately mobilized more than 400 health-care personnel to assist with the recovery from the catastrophe. However, the Cuban internationalist health-care program went beyond emergency relief. As 1999 closed, 467 Cubans were serving in nearby Haiti and 154 in far-away Gambia. Cuba’s export of its medical doctors, nurses, and health technicians were mostly the result of bilateral agreements, but Cuba had also deployed 11 health-care personnel under United Nations auspices to Kosovo.

As the decade closed, Cuban leaders worried considerably about the prospects of U.S. military actions in Cuba, especially after Fidel Castro’s passing. To make the U.S. government think twice before committing its troops, Cuban leaders sought to re-establish some kind of relationship with the Russian military, even if only at the symbolic level. Cuba’s Generals, therefore, were thrilled to welcome Col. General Valentin Karabelnikov, of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, during his visit to Havana in December 1999. He was greeted by his Cuban counterparts, Division Generals Julio Casas Regueiro and Jesus Bermúdez Cutíño. Of course, Russian military officers were commonplace in Havana from the 1960s through the 1980s but much less common in the 1990s. This visit helped the Cuban government make the point to the U.S. government that the Russian military still cared about Cuba..

Cuba’s political leaders characteristically become quite visible in end-of-year rounds of meetings, and 1999 was no exception. National Assembly President Ricardo Alarcón emphasized his double role. He was still the manager of Cuba’s relations with the United States, then in the midst of a migration crisis over Elián González’s fate, and he was also the guardian of Cuba’s formal institutionality, seeking at the same time to improve the performance of Cuba’s justice system and environmental protection.

Party Political Bureau members José Ramón Machado and José Ramón Balaguer sought to strengthen the provincial and local organizations of the Communist party of Cuba. They toured Cienfuegos province in December 1999 to praise its accomplishments but also to note many deficiencies. Party cadres behave as bureaucrats, not as political leaders, they observed. Party resolutions are formulaic and ineffective. Discussion at meetings is stiff and ritualistic. The party’s relations with workers or with young people left much room for improvement. Machado and Balaguer knew that the Communist party still has to reinvent itself.

And Women’s Federation President Vilma Espín publicly pondered why women’s roles in Cuban electoral politics had changed so little. Cubans have been electing municipal assembly members in multi-candidate (albeit single-party) elections since the mid-1970s. As the 1990s closed, a good Marxist-Leninist might believe that the objective conditions had ripened for more extensive participation by women in electoral politics. Consider Pinar del Río province, which Espín visited in December 1999 for a meeting of the provincial branch of the Women’s Federation. Women accounted for nearly 45 percent of the civilian work force in the state sector, including nearly two-thirds of the technical and over four-fifths of the administrative personnel; the party’s first secretary in the province (an appointive post) was a woman. Yet only 14.3 percent of the elected municipal assembly members were women. Why were Cuban voters so reluctant to elect more women to local city councils, given that so many women were clearly well-trained?

There were also the more anonymous faces of ordinary Cubans who remind us that, notwithstanding the good things that happened in Cuba in 1999, much is still woefully wrong in the country. Consider three examples. Cuba’s political and economic leaders were rightly proud that unscheduled electric power blackouts, common in the early 1990s, had become much less frequent as the decade ended. Nonetheless, massive electric power failures still recurred. On December 21, the electric power supply to the city of Pinar del Río and six other municipalities in Pinar del Río province failed. It took twenty-two hours to restore electric power – a period of time that the paragon of perpetual optimism, the daily official newspaper Granma, celebrated for its short duration.

A second example speaks to the question of efficiency and quality control, no doubt much improved in Cuba in 1999 but still quite unsatisfactory. On July 7, Osvaldo Milián, from Cienfuegos, found a box abandoned on the highway. It contained imported electrical equipment worth about $2000-3000, the equivalent of not less than fifteen years of wages at the equivalent level of Cuba’s current median salary. Milián contacted the local newspaper and radio to advertise the fact of his finding in order to locate the enterprise to which the equipment belonged. Several enterprises called to claim the box, but none could describe its actual contents. In December 1999, the rightful owner had not been found. Inventory control remains a goal yet to be achieved more fully.

The third example indirectly relates to Cuba’s readiness to cope with international tourism, the nation’s best hope for accelerating its economic recovery in the years to come. Alejandro Moreaux had been serving in Namibia in an international mission on Cuba’s behalf. To prepare for his return to Cuba, he shipped his belongings from Namibia to Santiago de Cuba on June 28,1999. They reached the Varadero international airport on July 17, where the cargo sat for four days. It was then shipped to the Havana international airport, where it then remained for 37 days. It finally reached Moreaux in Santiago on August 27. While Moreaux was not a tourist, such miserably poor handling of luggage reflects badly on Cuba’s tourist capacity. The decade also closed on an unhappy note for Cuba’s civil aviation, with major disasters (and many casualties) aboard Cuban airplanes in Guatemala and Venezuela.

Another public and private face of Cuba was evident as well at Christmas time. For the third consecutive year, the government declared Christmas day a holiday. Jaime Cardinal Ortega, Archbishop of Havana, led perhaps the largest outdoor procession since the Pope’s visit in January 1998. It was certainly the largest public march of the year that had not been sponsored by the Cuban government, Communist party, or official organizations.

Finally, the capacity of the Cuban government for authoritative nonsense was on full display as 1999 ended. Rosa Elena Simeón, ordinarily a competent and sensible government official, issued a signed press release on behalf of the Ministry of Science, Technology, and the Environment. The Minister explained that the millennium ended at the end of the year 2000, not at the end of 1999. Consequently, the Cuban government did not celebrate the end of the millennium on 31 December 1999; it would forego tourist riches and it would behave as a know-it-all grouch. Perhaps, as in instances past, the political leadership would turn this minor fiasco into a new “victory” by celebrating the noisiest and most fun New Year’s Eve party on December 31, 2000, proving yet again the superior wisdom of its leadership!

Winter 2000

Jorge I. Dominguez is the Director of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University and a member of the DRCLAS Executive Committee. The Clarence Dillon Professor of International Affairs at Harvard, he is the author and editor of dozens of books on Latin America, including Cuba, Order, and Revolution (Harvard University Press, 1978), To Make a World Safe for Revolution: Cubas Foreign Policy (Harvard University Press, 1989), and Democratic Politics in Latin America and the Caribbean (Johns Hopkins, 1998).

Related Articles

RFK Professor Roberto Schwarz

Roberto Schwarz, Robert F. Kennedy Visiting Professor this past semester, is one of the foremost Latin American intellectuals whose critical work spans 25 years. Students who took his Romance…

Resistance and Reform

A university chemistry professor in Havana quietly mixes chemicals-paid for by the state- for a local photographer. The photographer in turn sells some of his pictures to a Spanish tourist…

Reminiscences of the Botanical Garden at Central Soledad

The bus-it was Greyhound, I believe-took us all the way from Boston to Key West that summer in 1940. Then we boarded the ferry to Havana and finally the night train to Cienfuegos in the middle…