Difference and Repetition

The Argentinean New Wave

“Despite distance, we all belong to one or more service providers: the old boy Century Club network, the gay curators, the ex-pat New Yorkers, the wannabe Eurotrash, the genuine Eurotrash, the international upstarts, the desperately fashion-conscious deans, the desperately everything-conscious journalists, the p.c. nags, the young academics, the unionized staff, the kids-in-the-know, those-who-haven’t-heard-anything, and the Argentines.”

—R.E. Somol, “Pass it on…,” Log 3 (Fall, 2004): 6

Although jocular in tone the remark by Robert E. Somol, a leading architecture critic and historian, alludes to the status of the Argentines as a distinct group in architectural culture. The following excerpts from interviews with a number of Argentine architects practicing in the United States today will examine the various constituents and interests of the group and situate its energies within a broader historical context.

Spanning the course of four decades and occurring in two distinct waves, a significant number of Argentinean architects have exerted a profound influence upon the discipline and experimental practices of architecture in the United States today. Indeed, each group is inextricably linked to specific trends of postwar avant-garde architecture, and can be related to two specifically charged episodes in architectural discourse.

The first group consists of Argentinean émigré architects embedded at the core of Ivy League schools and the leading architectural schools in the country. They include Rodolfo Machado and Jorge Silvetti at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Diana Agrest at The Cooper Union, Mario Gandelsonas at Princeton University, Emilio Ambasz, Rafael Viñoly, and Cesar Pelli at Yale University. Many of these architects studied together at the University of Buenos Aires (UBA), and later at the Centre Recherche d’Urbanisme in Paris in the late 1960s, a period coinciding with the political and social unrest unraveling Argentina throughout the 1960s and 1970s which undoubtedly informed their decision to remain abroad. Heavily influenced by French literary theorists such as Jacques Lacan, Roland Barthes and Gaston Bachelard, this first wave of Argentine transplants were among the first to explore the relationship between Architecture and Semiotics, Linguistics, Structuralism and later Post-Structuralism. Prolific writers and dedicated educators, the first generation of Argentinean émigré architects have remained instrumental in the field of architecture and their thinking continues to resonate today.

The second, more recent generation of Argentinean architects—the new wave of experimental designers and thinkers—includes Hernan Díaz Alonso, Juan Azulay, Pablo Eiroa, Georgina Huljich, Mariana Ibañez, Ciro Najle, Florencia Pita, Alexis Rochas, Galia Solomonoff, Marcelo Spina and Maxi Spina, most of them interviewed for this article. Like their predecessors, most of these young architects received their early training in Argentina—Diaz Alonso, Huljich, Pita, Spina and Spina at Universidad Nacional de Rosario; Azulay, Ibañez, Najle and Rochas at UBA—before traveling abroad to complete post-graduate degrees at universities invested in more avant-garde design and theory. The majority graduated from Columbia University (with the exception of Huljich who attended University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), Ibañez who graduated from the Architectural Association in London, and Rochas who was at The Cooper Union in New York), and it is important to note that during the late 1990s and early 2000s when this young generation completed their studies these schools were pioneers in the realm of digital computation, fabrication, and conjectural modes of architectural formalism.

Today, many of these young architects practice on the West Coast, established—like their earlier counterparts —within the most influential academic circles (Southern California Institute of Architects (SCI-Arc) and University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and as leading voices in both academe and architectural practice, while a few have remained on the east coast, equally invested in speculative practices and teaching (Harvard GSD and Columbia GSAPP). The following interview is a highly edited, associative compilation of answers to broad questions probing the idea of a possible Argentine collective informed by the obvious filiations of their shared backgrounds, their disciplinarian affiliations, and the relevance of their new contexts. Whether or not their postcritical, computational, Deleuzian take on the discipline is directly informed by its collective backgrounds will remain subject to interpretation, but what is certain is that their contribution to the discipline and the rigor brought to Architecture by their collective intellect is as relevant today as it was four decades ago.

MG: Do you consider yourselves part of an intellectual collective of Argentinean architects that have a strong and defined presence abroad, and as such, were figures such as Machado, Silvetti, Agrest, Gandelsonas, Pelli, Ambasz, Viñoly, a point of reference to you when you decided to study abroad and establish yourselves outside of Argentina?

ROCHAS: First of all let me start by saying that being Argentinean is a really interesting fiction, a type of fiction I very much embrace. There’s a whole history of literary movements trying to define the country. I do believe this is an incredibly fresh way to identify oneself. And that’s the culture I come from. As far as if there’s an Argentinean collective; not really. I think it’s more like water in the landscape, it somehow, for some reason, finds its way down to the ocean, transforming the landscape as it runs. Our reasons for leaving were very different from those of an earlier generation, and so their trajectories were not considered as a reference point. I came here at the height of Menemism when the country was booming with strenuous exuberance, it was a good time to move on. As opposed to my predecessors who may have moved for other reasons—political or whatever it was. That sets a very different tone from the previous generation.

IBAÑEZ: The presence of Argentineans is quite evident in the architectural landscape of the US, and while I am aware of my compatriots, their work and academic influence (and, most importantly, their friendship) I certainly endeavor to establish my own pursuits. These are based on criteria that are not necessarily shared by—or mindful of—a collective model. However, our domains of interest do overlap and I am interested in and intrigued by their production in regards to the discipline. The cultural environment in which we were raised remains within us all, but broadly speaking, I could identify two factors that served as triggers when deciding to live and practice abroad: one that is internal to the profession—the search for a different intellectual environment—and one that is external and related to conditions of context.

MAXI SPINA: I like to think of myself as belonging to somewhat of a collective consciousness, maintained by a group of architects (namely, Hernán Díaz Alonso, Georgina Huljich, Florencia Pita and Marcelo Spina, to name a few), characterized, by and large, by a critical attitude towards architecture and culture in general. This collective consciousness, I believe, is not exclusively Argentinean, nor does it belong to the realm of the so-called critical regionalisms—hardly an operative term—but it constitutes itself as the conviction, among a few architects, that architecture needs not to be grounded as a service profession, but rather as an instrument of our intellectual and cultural becoming.

NAJLE: The notion of what a collective is has changed together with us, so I would say yes, even if the process was not, and is not, commanded ideologically. There is certainly a common ground, and numerous connections between us have evolved over the years, including a tacit acknowledgement of our differences, which are played out in the various contexts wherein we operate. It is clear that the culture arising in the nineties at Columbia as well as the profound influence of computation in architecture over the last decade have influenced us all. And this is still present in the work, no matter how far we may have distanced ourselves from those sources. We were driven by cultural motivations at first and by the dynamics of the cultural market after. Our move was probably less ideological and more personal—or self-seeking—than that of the previous generation. We did not ‘leave’ Argentina as much as we were interested in expanding our intellectual and professional horizons. The fact that the previous generation succeeded in its migration served as a precedent: we followed paths that had already been proven to be possible.

DIAZ ALONSO: Well, no, because that would sound like it’s been an orchestrated or choreographed effort, and I think this happened more as a happy accident. There are also different trajectories to be considered—myself and others come from Rosario, which had different sensibilities from what was happening in Buenos Aires. In any case, I’m always suspicious of collective efforts. I agree with Groucho Marx: “I don’t want to be part of a club that has somebody like me as a member.”

PITA: I think it’s hard to say because, for me, the main problem is cataloguing a generation. I think there’s a lot of chance in all of this. There are particular events that occurred, and somehow these created a chain reaction. I would say that for the group of us here, the model was “transitional” —Galia introduced a group of us to Columbia when she visited Rosario. Marcelo was then the first to attend, then Hernan, then I, then Juan, in sequence. That’s what I call the chain reaction. The grouping of Argentineans in LA happened through another university affiliation, in this case SCI-Arc. Hernan started teaching, then came Marcelo, then I, then Alexis, Juan. It’s hard for me to pinpoint the relationship between us and previous generations because it has less to do with the recognition of a particular background, and more with a discovery of a new methodology.

MARCELO SPINA: Perhaps at a personal level because we share academic formative experiences and disciplinary environments. However, particular kinds of work from each individual begin to associate each of us with different people independent of their nationalities.

HULJICH: Yes, but in the sense that collective may mean being related to people from the same generation that have left the country at the same time and share many interests, not because a similar discourse might add to an understanding of our work. In a way I do consider ourselves influential in the new generation of practitioners, although I don’t consider the earlier generation as a direct point of departure. I think that has much to do with being on the West Coast. Many of the people you mention are on the East Coast and not necessarily related to Columbia, the closest relationship we built while being in New York for two years.

SOLOMONOFF: As I grow older, and as my influence deepens as a teacher, I have a stronger sense about an Argentine collective and I admire the efforts of everyone involved before and after me. I realize that there are traces in common yet not as strong as other collectives like the Madrid Club, for example. The sense of belonging to several communities has intensified, I am aware of the particularities of being an Argentinean woman practicing architecture in New York. Diana Agrest and Florencia Pita have helped establish the respect that comes before and after. In our office, SAS, we always have a young Argentinean architect, currently Ignacio Guisasola. I find that as a collective we combine theory and practicality, humor and horror with a unique ease!

AZULAY: I think we all feel that we are our own individual Diaspora, broader than Argentina. That’s the Argentine amnesia anyway. The closest thing to a nation we have is the possibility of our soccer team. However, looking back, you could begin to recognize cyclical diasporas. I think that for us, more than the references cited, it was Columbia or New York that served as the hinge point where these things came together and connections were forged. But it is strange that the patterns are convergent.

MG: Would you be able to discuss your professional and intellectual development in relation to your cultural and/or academic/formal background? How do you see your education and upbringing in Argentina playing a role in your personal work?

HULJICH: The education in Argentina is excellent. I believe we are very well prepared, and that this has played a very important role. We have a background that allowed us to learn new methodologies for making. It’s a type of background that allows you to be highly selective and not to just buy into anything that is presented to you.

MARCELO SPINA: My education in Argentina was incredibly important since it gave me a kind of ethics and rigor that I never got in the United States as a student. The foundation of what we do as architects can be traced to my former education there. Since we are not only involved in speculative work, but also in building it, that formative experience is still very valuable.

ROCHAS: Absolutely. I’m the product of public education. I am from Buenos Aires and I went through an incredible, however traditional, free, public school system that has an incredible potential. It has its limitations over the course of time, and given my own curiosity, I tried to transcend those limitations by moving abroad and experiencing a second wave of education, so that’s why I went through two undergraduate degrees—one in the University of Buenos Aires (UBA) and one at Cooper Union in New York. I think it took me five years to learn architecture, and it took me another five years to deconstruct it or pull it apart or undo what I knew what to do before.

AZULAY: I came to SCI-Arc in 1993 as an undergraduate late transfer, so I was able to complete my basic architectural military camp at the University of Buenos Aires, with its very rigorous training and its mechanical time-management-based skills. I recognize I was very fortunate to have received a disciplined and rigorous training in my early education, and later, at SCI-Arc, I worked with people willing to take me to the edge of the cliff.

MG: Are there any explicitly cultural-political moments in Argentine history that may have affected your understanding of your current environment/practice?

ROCHAS: I grew up with a country trying to figure itself out after twenty years of dictatorship, so in a way, I see the country as experimenting ever since. There’s no laboratory as big as Argentina, they keep experimenting today. It feels like a really awake country, they experiment economically, politically—some of the experiments fail, others transcend expectations, but the experimentation is continual. I always say that if the EU would work as an integrated utopia, it would very much look like Argentina.

SOLOMONOFF: I think, as an Argentinean—and as an immigrant—I am always ready for something to go wrong and to find a solution. I think we are conditioned, as kids of the dictadura, to understand double talk, to work hard, and to wait for gratification one day in some dreamed future.

NAJLE: I recognize the relative inconsistency of our background, and I consider it to be an intrinsic and deliberate cultural-political condition of our work, and not merely as a lack of position. We recognize that our speculations are developing in what one could understand as a mid-situation between the ironically paralyzing political activism of previous generations, and the underdeveloped criticality of those who have emerged since.

The model where practice and academia are both an integral and indispensable part of architectural enquiry is one that I learned in Argentina and luckily managed to develop in my experiences abroad. My education from various institutions in Buenos Aires was excellent, and I’m seeing many young architects in Latin America doing very interesting work. In the past, the distance from Buenos Aires to Europe and other cities of the world seemed to create a separation from contemporary discourse but the community is now more widespread and networked and characterized by local intensities.

AZULAY: Absolutely, I mean there’s a hard wiring that we Argentineans have. Someone once said, Argentineans love their dictators. In a way, it means coming to terms with our own DNA. Growing up, we were dealt with an even weirder hand than our predecessor[s] who were thrown out of planes, drugged alive, made to disappear. Our death planes were imaginary creatures, where we didn’t die, but were repeatedly thrown out. It’s an intangible, invisible form of violence that festers like a void. Without knowing it, I believe we inherited that void, and then had to invent our own space.

MG: How strong is your connection to Argentina and do you see your work and disciplinary interests having a resonance back home?

IBAÑEZ: The research and work of my practice is multi-variant—we produce architecture that is classically recognizable as static form responding to site and programme, but we also interpret architecture as a changeable domain, with interactive and augmented response in service of new relationships among environments and occupants. The location of Cambridge is ideal for this research with its proximities to people of expertise in many disciplines. Argentina as yet does not have this specific interest although we see aspects of it emerging.

HULJICH: I think our practice has more resonance outside of Argentina than within the country. For us it has been, and still is, an amazing showroom. Being able to have three built projects is an opportunity that many people haven’t had, and we’re very grateful for it, but we’ve been more recognized for them outside of Argentina. People look at our buildings, maybe without saying much, but still appreciate what we do.

DIAZ ALONSO: Incredibly strong in personal terms since we have family living there, but that is pretty much it—professionally and intellectually I have zero interaction with Argentina.

MG: You’ve been living abroad for about a decade—how much do you think the influences of the city have played a role in your work?

HULJICH: In general, the dynamic nature of Los Angeles requires many years to grasp, and in a way, you need to build your own infrastructure. Once you do, you own it. I feel like I own the part of the city which I know. You have to customize it to your own interest. It means that you can follow your own ways. The horizon of opportunity is endless because there nothing is set.

MARCELO SPINA: Certainly the city has had a profound impact in who we are as architects. The entertainment, aeronautic and automotive industry, the technology available for material fabrication and the fearless spirit of innovation of Southern California is extremely important and attractive to us.

PITA: I always say I received my education in Rosario, my extended education in New York with Peter [Eisenman] and at Columbia, and then my double degree in LA working for Greg Lynn for five years. I think this experience really marked me, and I suppose that’s the LA influence. I see it as “transferred influence.” Greg was one of the precursors of having the architectural education engage with the fabrication industry that came from the movie industry.

ROCHAS: LA, I consider it a mirage. A mirage is something that flickers—sometimes it disappears, sometimes it manifests itself. Sometimes there are beautiful clouds of smog covering all of the mountains and there is no landscape… other days the wind blows and suddenly you discover a whole landscape buried behind.

AZULAY: I think Los Angeles offers more space and a better conflation of forces than anywhere else. I’m interested in the cultural imaginary in-between that lies within the territory of LA and its heterogeneous, non-linear, high-intensity, low-frequency environment, as well as the mediated moment that Hollywood might offer. In its fringes lies the furtive component so compelling to the city. And ultimately, its materialization is behavioral rather than formal.

DIAZ ALONSO: Gigantic. I don’t actually have any interest whatsoever in the material aspect of architecture. When we build we deal with that aspect but it’s not something that interests me for investigation. I think it has to do with my ambition to keep everything in a kind of dynamic and cinematic logic. I will be the first to recognize that I’m much more obsessed with image than the physicality of form. So LA and I are made for each other. I like seeing the pictures more than seeing the object in reality. And nothing seems to be completely real here.

NAJLE: I would say that New York has had a strong influence in my aesthetic commitment to the brutal and the sublime, in my engagement with infrastructure, in my predilection towards wild and blunt material organizations, and in my preference for strong ‘anti-detailing’. It has also helped me to develop a certain freedom, perhaps boldness, in relation to the appropriation of historical materials. London’s influence is less object-driven and more about mind-set. I think its power lies in my attraction towards consistently elaborated forms of sophistication, in my attention to the excessively cultivated, and in the value I give to common sense: the beautifully constructed and strongly preserved sense of what has become ‘common’. Both cities have also taught me a lot about ideological agility and trained my sensitivity towards the forecasting of cultural trends.

IBAÑEZ: London was a uniquely catalytic experience – it is from my graduate education at the AA and work with people like Cecil Balmond and Zaha Hadid that has established strong points of reference for me as an architect. Congruently, Cambridge is home to extremely powerful institutions with resources, facilities and people and our contact with them have fundamentally changed the way we practice. I am interested in defining polemical positions and imagining new environments as a result of the overlap between expertise that is considered architectural and expertise that produces architecture but comes from somewhere else. In this regard, both London and Cambridge have been instrumental.

SOLOMONOFF: Life is a journey and it makes more sense if you recognize where you started.

See a slideshow of works by the architects interviewed by clicking here.

EXPANDED INTERVIEWS AVAILABLE ONLINE ONLY

Interview with Hernan Diaz Alonso

Interview with Juan Azulay

Interview with Georgina Huljich

Interview with Mariana Ibañez

Interview with Ciro Najle

Interview with Florencia Pita

Interview with Alexis Rochas

Interview with Galia Solomonoff

Interview with Marcelo Spina

Interview with Maxi Spina

Spring | Summer 2010, Volume IX, Number 2

Maria Guest, based in Cambridge, is co-Principal of Sharif Guest Studio, a collaborative design practice with Mohamed Sharif. Guest currently teaches at Rhode Island School of Design. Prior to teaching, Guest was Project Manager at Office dA, and from 2000 to 2006, Guest led the team for the US Courthouse in Eugene, Oregon, as Project Leader for Morphosis Architects in Santa Monica. Guest graduated from the GSAPP at Columbia University in 1996, where she was the recipient of the Outstanding Thesis Award, and the William Kinne Travelling Fellowship.

The Architects:

Hernan Diaz Alonso is the principal and founder of Xefirotarch, based in Los Angeles. He is Distinguished Professor of Architecture at SCI-Arc, Design Studio Professor at Columbia GSAPP, and Head Professor of “the EXCESSIVE program” at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. He worked as a designer in the office of Enric Miralles in Barcelona, and was senior designer at Eisenman Architects in New York. Diaz Alonso received his architecture degrees from the National University of Rosario, Argentina, and from Columbia University’s AAD Program, from which he graduated from with honors.

Juan Azulay is the director of the 10-year-old Los Angeles-based firm Matter Management. His award-winning practice ranges widely in discipline, methodology and media. Azulay received his B.Arch. from SCI-Arc and his Master of Science in Advanced Architectural Design (MSAAD) from Columbia. He is currently on the Design, Mediascapes and Visual Studies Faculty at SCI-Arc.

Georgina Huljich graduated from the National University of Rosario, Argentina and received her master’s degree from the University of California, Los Angeles. She is co-principal of PATTERNS and Design faculty and JumpStart Program Director at the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA. She was the 2005-2006 Maybeck Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.

Mariana Ibañez is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. She received her first degree from the University of Buenos Aires to then attend the Architectural Association in London for her Master of Architecture. After her graduate studies, she joined the Advanced Geometry Unit at ARUP before going to the office of Zaha Hadid. In 2006, Mariana relocated to Cambridge and co-founded I|Kstudio with partner Simon Kim.

Ciro Najle, an architect and design critic at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, is the Director of General Design Bureau in Buenos Aires and of Mlab in Valparaiso. He has taught at the Architectural Association, the Berlage Institute, Cornell AAP, Columbia GSAPP, the UTFSM in Chile, and the University of Buenos Aires.

Florencia Pita was the 2000 Fulbright-Fondo Nacional de Las Artes Grantee. She graduated with a Bachelor’s degree from the Universidad Nacional de Rosario, School of Architecture, and a Master’s Degree from Columbia University MSAAD program. Pita is the principal of FPmod and is a Full Time Faculty at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) in Los Angeles.

Alexis Rochas is the founder of I/O, a Los Angeles based practice focusing on the development of dynamic architectural methodologies integrating design, technology and advanced fabrication techniques. Rochas is a full-time Design Faculty at SCI-Arc and Program Coordinator for Making and Meaning, SCI-Arc’s foundation program in Architecture.

Galia Solomonoff earned a Masters in Architecture from Columbia University in 1994. She is founder and principal of Solomonoff Architecture Studio, and has been internationally recognized for her work. Solomonoff is currently Associate Professor at Columbia University GSAPP.

Maxi Spina is an Adjunct Professor at California College of the Arts since 2008. He was a Senior Designer at Studio Daniel Libeskind in New York from 2005-07, and taught at the National University of Rosario, Argentina and University of California, Berkeley, where he earned a Maybeck Fellowship in 2007-08.

Marcelo Spina graduated from the National University of Rosario, Argentina and received his master’s degree from Columbia University in NY. He is founder and co-principal of PATTERNS and Design and Applied Studies faculty at SCI-Arc. He was Visiting Professor at Harvard University; University of California Berkeley; Tulane University and University of Innsbruck in Austria.

Related Articles

A Tale of Three Buildings

Greek columns, in Thomas Jefferson’s designs for the University of Virginia, might evoke democracy. In Albert Speer’s designs for Berlin during the Third Reich, similar columns serve to…

Poverty and Poverty Alleviation Strategies in North America

The eight essays in this volume, coedited by Mary Jo Bane, Thornton Bradshaw Professor of Public Policy and Management at the Harvard Kennedy School, and René Zenteno, Professor at…

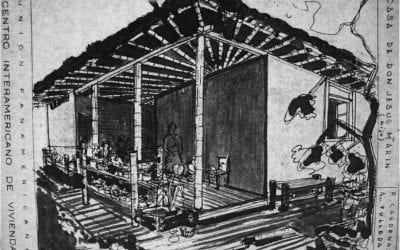

Productive Workers for the Nation

In 1954, Colombian architect Alberto Valencia took a short trip to the small town of Anolaima, two hours away from Bogotá. An architect at the Inter-American Housing Center—a joint project…