(Dis)locations of Violence in Latin American Film

Displacement and Visual Representations

Transitioning back to cold in Boston invites me to a weekend of movies on Netflix. A curiosity self-justified, as research interest cascades into shameless binge watching of two seasons of Narcos, followed by a re-watch of El Patrón del Mal. “Because you watched Narcos,” Netflix points me to La Reina de Sur, El Cartel de los Sapos and El Capo. Inevitably, I find myself going back to other violence-related films such as Blow (Ted Demme, 2001), Traffic (Steven Soderbergh, 2000) and Sicario (Denis Villeneuve, 2015). No matter the format—television series, telenovelas, movies—these productions somehow reduce and somewhat glorify specific characters and episodes of Latin America’s recent history of crime and violence. They all share a common thematic focus: the region’s problematic relationship with the drug trade. But this is only part of a bigger picture—both of violence and its representation in the visual arts.

Since the 1960s and 70s, displacement and violence in Latin America have been represented widely in cinema, video art, and—later on—in television series. Film in particular is a fitting form to portray violence since there is, in a way, a double rupture in the expression of violence through film. Violence as such, is not experienced in a structured manner—it implies a break in the sense of personal or collective narrative. Similarly, the dislocations between text, images and sound are inherent to film as a medium. For instance, when a character faces the camera in a close-up, there are several ruptured elements: his visual field (whom or what is he seeing?), the imageless voices and sounds around him, and so on. The spectator is, at the same time, in the position facing the character on the screen, sharing the auditory experience of that character on close-up, and missing visual access beyond the frame. Thus, the relation between story and spectator is, in many ways, a mediated and incomplete experience. In addition, the narrative elements, images and sounds are continuously re-shuffled from one scene to the next—despite the perception of continuity, in film, essential discontinuity exists even at the sole level of images. These ruptures push the spectator’s gaze and overall experience in different directions—just like the concrete fact of displacement.

The work of Cuban artist Ana Mendieta with her multidisciplinary art (as per her own dodging of categorization), moving between performance, sculpture, photography and film, carried this sense of displacement even further. She engages the body—her own body: as actual presence, or as shadow or silhouette—with blood, fire, water, and earth. Mendieta’s work is deeply personal and, at the same time, a definite expression of what Howard Oransky describes as “a larger collective experience, which included the dislocations characteristic of the modern era: personal, cultural and political displacement” (Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta, University of California Press, 2015). Her exile from Cuba as an adolescent, and a shared human condition of instability (product of mortality and our constant facing of time) are equally expressed both in material (i.e. physical) and temporal terms.

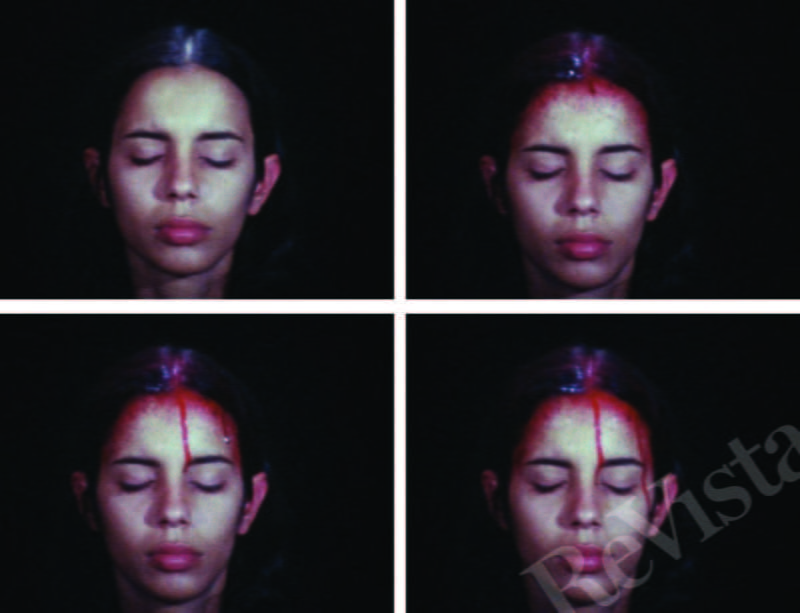

But in Mendieta’s films, the connection with time goes a step further. While they retain the evocative tone of her photographic work (evocative of violence, displacement, time lost, the body, nature), in film, the subtle pace adds to a heavy silence, heightening a sense of imminence, of a violence that doesn’t explicitly materialize. In Sweating Blood (1973), the camera captures a motionless close-up of Mendieta’s face, her eyes closed. Slowly, blood starts flowing from the top of her head, down her face. The face remains still, while the blood puddles up. Another film, Blood Writing (1974), shows Mendieta with her back to the camera facing an exterior white wall. Slowly, with blood taken from a container, she spells out with her hand the words “SHE GOT LOVE” on the surface. Her shadow remains on the wall after she leaves the scene. Mirage (1974), in contrast, sets a complex mix of elements and sense of narrative: a landscape, a mirror, the image in the mirror of a nude pregnant woman, and an almost accidental—although very much intended—over-the-shoulder shot, presumably of the artist. The motionless pregnant woman’s image builds tension, intensified by the subtle movement of grass surrounding the mirror. After a pause, she brings out a tool and cuts her belly open. Out of the womb, come handfuls of feathers, repeatedly. In all these works, stillness fades gradually, confronted by dislocating elements. Violence is presented, although not present.

In feature films—to distinguish from experimental films in the visual arts, such as Mendieta’s—through the 1960s and 70s, filmmakers mainly from Latin America, Africa and Asia developed an independent movement with its own aesthetics, production methods, and political voice: a “Third Cinema.” Highly influenced by Italian neo-realism, but also by other experimental trends such as cinema verité and the French New Wave, this movement meant a break with Hollywood and other commercial and mainstream traditions, including the European art film. New technologies allowed for a revolutionary (i.e. political and experimental) cinema that exposed the historic and prevalent conditions of the colonized: collective and national experiences of poverty, inequality, displacement, violence and other forms of oppression. Some films from Latin America of this period include: Memories of Underdevelopment (Tomas Gutierrez Alea, 1968), Black God White Devil (Glauber Rocha, 1964), The Hour of the Furnaces (Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getina, 1968), and Barren Lives (Nelson Pereira Dos Santos, 1963). Third Cinema led not only to making films, but also film theory and criticism in texts such as Glauber Rocha’s Aesthetics of Hunger (1965) and Toward a Third Cinema (1969) by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino. Rocha, in Aesthetics of Hunger, brings up the European nostalgia for primitivism in Latin American art: “… while Latin America laments its general misery, the foreign observer cultivates a taste for that misery, not as a tragic symptom, but merely as a formal element in his field of interest.” Displacement is crucial as theme and as form, not only in the films, but also in the theoretical framework that connects these works beyond their national and regional bonds.

Later Latin American films are also highly aesthetically complex, political, and crucial in a discussion about violence and displacement. For instance, Patricio Guzmán’s masterpiece The Battle of Chile (Chile, France, 1975) and Luis Puenzo’s The Official Story (Argentina, 1985) are key representations of the region’s history of dictatorships, forced disappearances and other forms of oppression. But contemporary films from the 21st century deal with matters of violence and displacement in a less explicit, but not less compelling and committed manner.

THE OTHER: THE HEADLESS WOMAN

Lucrecia Martel’s The Headless Woman (Argentina, 2009) is a story of a road accident and its psychological aftermath: events misremembered, guilt, complicity, and, in terms of style, bodies half shown or seen in passing, repeated gestures and haunting sounds.

The story is minimal: Veronica, a middle-class woman, is distracted by her ringing cell phone and runs over something (or someone?) on the road. This is the same road from the opening sequence, where three kids—the class gap apparent—were carelessly running and playing with a dog. At first paralyzed, while a cheerful song plays on the radio, she puts her sunglasses back on, fixes her hair and turns on the engine. As she drives away, the camera moves to a long shot of the road and what, at a distance, looks like a dead dog. The film has been running for only six minutes. The rest relates to Veronica’s mental swings between denial (confusion, avoidance, attempts at normalcy) and guilt (self-doubt, emphatic confessions). But the details insist and accumulate: hand prints on the car window, phones ringing, Veronica’s hair, the wrecked car, the hospital, the hotel where she spent the night, and the kids from the first scene—minus one. What is relevant? Moreover, in the end, the status quo is restored, precisely, in the details. Traces from the hospital and the hotel are gone, the car is fixed, the missing child is replaced, and Veronica’s hair goes back to dark.

The accident is startling and the notion of the dead child (regardless of whether he was hit or he drowned) is disturbing, but nothing graphically violent really happens. The most palpable violence in Martel’s story is class related. Not only in the premise that the poor are replaceable and their absence solved by “handling” traces, but also in trivial interactions at home, with vendors, and so on. In a casual conversation at the swimming pool, the women mention not getting their heads in the water, in case it’s contaminated—a seemingly banal statement, but full of meaning. Additionally, Martel formally creates a disorienting atmosphere through sound, camera movements and odd framing. For instance, in the opening scene, the road is shot from a tilted perspective, the curves half hidden, while the kids’ bodies move in and out of frame, stressing their vulnerability. Also, disassociation is enhanced as Veronica moves out of frame when she gets out of the car after the accident. Sounds such as the phone, a ball hitting a fence and the turning wheels of the car wrecked in the accident are brought back to insist and make us aware of the existence of the other, even if we (that is, Veronica and the spectator) have to suspect having killed someone. The normalizing elements leave no space for normalcy.

SPECTACLE AND MARGINS: TONY MANERO AND MADAM SATÃ

Pablo Larraín’s Tony Manero (Chile, 2008) and Karim Ainouz’s Madam Satã (Brazil, 2002) are stories in which displacement is explored through identity: characters split between marginal life and a spectacle persona. But, despite sharing the focus on individual experience and identity, the search of Tony Manero’s protagonist for the “other” (that is, imitating the American cinema icon) differs from the complex and multiple experiencing of “self’ in Madam Satã.

Raúl Peralta is a fictional character, an impersonator of Saturday Night Fever’s protagonist, Tony Manero. Set in 1978, in the midst of Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile, Larraín’s film is not explicit about historic events, but is doubtless political, a fog which constantly permeates the atmosphere. Raúl’s cultural identity appropriation symbolizes a form of involuntary complicity with the United States and, thus, with the oppressive regime. Resistance, on the other hand, arises from secondary characters’ clandestine propaganda handling, as well as scattered allusions to a context of scarcity, crime and secret police. Acts of violence in this film are plentiful, some graphic, some merely allusions: a few murders and thefts, plus random events such as Raúl’s feeding an old lady’s cat after killing the woman, defecating on a competitor’s dancing suit, or in several sloppy sexual encounters.

Madame Satã, on the other hand, is based on a real character from Brazilian popular culture, João Francisco dos Santos (1900-1976), a drag performer who became known as Madame Satã—inspired by a 1930s film by Cecil B. DeMille. So this movie, as well, is the representation of a representation. Besides his stage persona, João Francisco is an outlaw, street fighter, unpredictable (sometimes madly laughing, then enraged) friend and father, elegant man and gay lover. In Rio de Janeiro’s underworld of the 1930s, issues of race, class, sexuality and crime come together in this extremely dynamic film that switches times, formats (documentary and fiction), settings, and various compelling characters. Dislocation is revealed through contrast: the fights and explosive reactions, the ecstatic body movements, and the frustrated attempts at being loved, accepted and even paid for work. The stunning body that wins several carnival competitions is also, as per the authorities verdict, the vehicle of “repulsive and criminal acts, an individual harmful to society.”

Equally powerful, these two films also have different aesthetic approaches. Tony Manero conveys a calculated dark and unpleasant atmosphere. The heavy pace, raw acting, oppressive settings, and unattractive bodies are met, formally, by the instability of a handheld camera and gloominess of the film’s grainy shots. In contrast, in Madame Satã rage and violence clash with the film’s overall beauty. High-contrast photography, frenzied movement and meticulous compositions deliver a lively and alluring mood. Ainouz makes the body a focal point: mainly the protagonist’s body that moves, sweats, glitters, fights, seduces, and physically changes between macho, thug, beaten-up murderer, and beautiful queen; but also others, among them the very effeminate Taboo, or João’s handsome lover, Renatinho.

OTHER DIRECTIONS: COLONIZATION, MIGRATION, AND MODERN LIFE

Portrayals of displacement and violence in Latin American film are frequent. A few additional works about colonization, migration and modern life struggles follow, to open a larger discussion in the future.

The Embrace of the Serpent (Colombia, 2016) is Ciro Guerra’s beautiful black and white movie, with quasi-ethnographic imagery. Two journeys—separate in time, but connected through the characters—explore commercial and cultural exploitation in the Amazon, with the last Cohiuano tribe survivor and a European white explorer moving across the territory in search of the yakruna, a sacred plant. The central themes are colonization, plus relations between colonized and colonizer, and migration. The movie puts at conflict the beauty of the land and cinematography, with the horror brought by exploitation not only of the territory and its indigenous tribes, but also of indigenous boys and tribes abused by white religion-linked figures. Questions about self and other are also raised in Lucia Puenzo’s The Fish Child, only from the point of view of modern class domination. The colonized figure, in this case, is a lower class Paraguayan immigrant in a love relationship with the daughter of her Argentine upper-class employers. Migration from Argentina to Paraguay grants the two a blank slate to escape the police, but also to come together as a gender and class defiant couple. Also, this movie touches on issues of sexual abuse and, more briefly, human trafficking.

Finally, Damian Szifron explores the dislocations and stress of everyday life, in Wild Tales (Argentina, 2014). Using a very different register, this dark comedy consists of six short films about characters pushed to the limit by highly relatable situations: love and work relations gone bad, financial ruin, road rage, bureaucratic abuse, high class impunity, and a wedding. These encounters end up in outrage and depression levels that lead to over-the-top reactions such as a deliberate plane crash, bloody fights and a deadly car explosion, detonation of explosives in front of a car-towing business, or a wedding turned into a hell of knives and mad sex. Asides from the explicit consequences, violence is expressed in humorous and styled scenes of repressed tension turned, finally, into brutality. The episodic format of the film formally enhances the atmosphere of daily, fleeting rage.

Displacement has many faces–violence, migration, oppression, among others—and so does its representation, especially in a medium as complex in its aesthetic possibilities as film. Unlike mainstream representations of acts of violence and other forms of abuse and repression, displacement in some of the works discussed here is hinted at or indirectly explored. The aesthetic limits of these films are pushed in different directions–some more visceral, some extremely calculated. In addition to the narrative content, atmosphere and imminence take the place of graphic presentation. Thus, displacements are not only thematic, but also an aesthetic that becomes particularly powerful in the choice of medium.

Winter 2017, Volume XVI, Number 2

Paola Ibarra directs regional and thematic initiatives in Cambridge at DRCLAS at Harvard University. She holds an ALM in English from Harvard Extension School, and an MSc Development Studies from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Related Articles

Urban Spaces of Internal Displacement in Mexico

When news came that the drug dealer Joaquín Guzmán, El Chapo, had escaped from a Mexican prison on July 2015, memories about cocaine cartels and urban gangs creating…

The Tupac Amaru Rebellion

On May 18, 1781, Spanish authorities in Cuzco executed José Gabriel Condorcanqui Noguera, also known as Tupac Amaru, in front of thousands of onlookers. Claiming to be the rightful…

A Search for Food Sovereignty

Displaced persons in post-conflict societies throughout Central and South America have been finding an unusual source of support: seed networks of food-growers…