Education and Poverty in Latin America

Can Schools Make Any Difference?

“The children of the poor face very limited opportunities to participate in economies ever more integrated into the world economy,” writes Fernando Reimers.

More Latin Americans are living in poverty than twenty years ago, despite the region’s economic growth. The poor generally are still illiterate or barely literate. What is worse is that their children have limited opportunities to learn. They do not get a chance to move out of poverty by acquiring skills and knowledge, although about nine out of every ten children in the region enrolls in first grade.

The dynamics of education in Latin America are a critical link in the intergenerational transfer of poverty. Equality of educational, and social, opportunity is central at this time in the history of Latin America because it will contribute to the perceived legitimacy of democratically elected regimes and their policy choices. Democratic consolidation requires a broad based understanding that the life chances of all citizens are a function of merit and ability.

There is a documented association between poverty and educational attainment in Latin America. The poor are those with lower levels of education. Because they have disproportionately more children most children in Latin America are poor. Although most poor children enter first grade, they enroll in schools of lower quality, and are more likely to drop out after completing a few grades. In order to reduce poverty in Latin America, we must first understand the simultaneous processes of how education reproduces poverty and how education fosters opportunities to learn and for social mobility for the poor.

At least one in three people in Latin America now lives in poverty. Thirty six percent of the population lives on less than US$2 per day at 1985 prices. For the structurally poor, it seems, prosperity has not trickled down during the last ten years. Countries achieving significant economic growth during the last ten years have not reduced the incidence of poverty. In Argentina, for example, economic growth more than doubled per capita income and led to increases in real salaries and to the creation of thousands of jobs. Yet, unemployment in that country has also doubled and about a quarter of the population has lived with unmet basic needs since 1991. The percentage living below the poverty line in Latin America has stagnated since 1980, according to World Bank studies. The percentage had declined significantly from 60% in 1950 to 35% in 1980

Educational opportunities are the key to provide Latin American citizens access to knowledge, to the opportunity to participate in the creation of wealth and to the opportunity to prosper. As the economy becomes more global and knowledge-based, those with the greatest access to knowledge will benefit the most from the opportunities resulting from the integration into the world economy.

In Latin America, the sharp inequalities in the distribution of income reflect themselves in equally sharp inequalities in the distribution of access to knowledge and skills. Some children participate and succeed in schooling, acquiring basic cognitive skills, world views and social experiences. Their education enables them to go on learning, to work productively and to participate socially and politically. The children of the poor have more limited educational opportunities, leading to school failure and a lack of opportunity to acquire the same cognitive skills, to partake in the views and social experiences associated with good schools. Many of them face very limited opportunities to participate in economies ever more integrated into the world economy.

A fair amount is already known about the relationship between education and poverty in Latin America. We know that the poor have lower levels of education and that income rises with educational level. In Latin America, 14% of adults 26 years and older cannot read or write at all. If we assume a sixth grade education is necessary to reach functional literacy and to acquire basic cognitive skills, the number of Latin Americans who are absolutely or functionally illiterate equals the number of people living in poverty.

Education and income are closely related. In Brazil, for instance, the poorest 40% of teenagers (ages 15-19) average four years of schooling, while their counterparts in the top 20% of income distribution have twice that average level of schooling. In Northeast Brazil the gap increases: the poorest 40% of fifteen- to nineteen-year-olds average only two years of schooling versus 5 years for the top 20%. In Haiti the poorest 40% of the youth average two years in school, while the wealthiest 20 % averages six years. In Guatemala the gap between these groups is 2 versus 6 years of schooling on average.

Indigenous Latin Americans suffer even more from lack of schooling. For instance, in Bolivia’s urban areas, the average non-indigenous person goes to school for ten years, Spanish-speaking indigenous people average six years of schooling, and those who do not speak Spanish have an average of 0.4 years of schooling.

The lower levels of educational participation and attainment among the poor in Latin America are a paradox in a region with legislation that mandates universal free primary education. We can understand this paradox if we think of educational opportunity as a series of steps in a ladder.

The most basic level of this ladder is the opportunity to enroll in first grade, an opportunity now enjoyed by the great majority, but not all, of Latin America’s poor children.

Considerable progress has been made in expanding access. In the last 50 years, the number of students at all levels in Latin America increased from 32 million in 1960 to 114 million in 1990. Only three out of every five children were enrolled in first grade in the early 1960s, but today 95% of nine-year-olds are enrolled in school. Enrollment rates since 1960 increased from 60% to 88% at the primary level, from 36% to 72% at the secondary level and from 6% to 27% at the tertiary level. These increased opportunities to enroll in school demonstrate a remarkable expansion of the education system and great efforts in building schools and hiring and training teachers, especially when one takes into account the burgeoning population.

It is generally between the first and second level of the ladder of educational opportunity that the poor fall behind in today’s Latin America. One out of every three children who enroll in first grade fail just as they are beginning school. Many of the poor have no preschool education whatsoever, and many teachers serving poor children have not been prepared to address their particular needs. For instance, many indigenous children are taught in a language and with materials they don’t understand. Grade repetition is disproportionately higher among the poor. Research shows that repetition leads to more repetition and eventually to school dropouts.

The third stage of educational opportunity gives students a chance to complete the first cycle of education, to achieve functional literacy, to do simple math, to establish cause-effect relationships, and to have basic information about science, history, social studies. Most of the children of the poor do not complete this cycle. One reason is that parents of children who must repeat grades find it increasingly impossible to continue supporting their studies. High repetition rates mean children only reach an average of fourth grade, even if they are staying in school longer.

The next level of opportunity means students in the same grade will learn comparable skills and knowledge. However, most students in Latin America don’t get this chance because schools are very segregated by family income and sometimes ethnicity. In general, students from low income families have the lowest scores in standardized tests.

The highest level of opportunity provides equal economic and social opportunities to students with equal skills. Thus, graduates of a given educational cycle will have the same options in life. This level of opportunity does not exist in Latin America. Studies have shown that indigenous workers, and especially women, have the same educational achievement and work experience as their mestizo counterparts, they generally still earn less money. It is not apparent that Latin American societies and labor markets have meritocratic systems to provide access to social and economic opportunities.

While Latin America has made much progress in advancing the first level of educational opportunity, many interlocking reasons prevent equality from being obtained at all levels of educational opportunity.

The first is poverty itself. The children of the poor have poorer health and nutrition; they have less time to spend on school activities and less support for homework, and they tend to be absent more from school because of poor health, family and economic needs. Thus, poverty perpetuates poverty.

Since poor children have very limited opportunities to quality pre-school, they are less ready for school when they actually do begin. The type of schooling they are offered is often not equal to that provided to better-off children. The schools and teachers are often of lower quality; there is less access to instructional materials and less time devoted to teaching.

Above all, there is a lack of compensatory policies, of positive discrimination, which would enable teachers to work effectively with disadvantaged children and which would provide them with instructional materials geared to their needs.

The impact of these factors is cumulative and compounded over time, as children reach higher levels of education. Low quality or no access to pre-school education makes it difficult for poor children to benefit equally from primary education; the resulting low quality of learning at the primary level makes it difficult to benefit equally from secondary education, and so on. As can be expected, very few disadvantaged children reach higher levels of education. In El Salvador, for example, only seven percent of the university students come from the poorest 40% of the households, while 57% come from the richest 20% of the households. As Latin American economies become more competitive a quality higher education becomes more important. The fact that most higher education graduates come from higher income groups leads to the consolidation of inequalities and lack of social mobility in Latin America.

The good news: the great potential of poor children and the difference schools can make

Although the children of the poor generally have on average lower levels of academic achievement than their non-poor counterparts, I have found in Colombia and Mexico that there is overlap in levels of achievement between the poor and non-poor. Some disadvantaged children have comparable levels of academic performance than children in significantly more advantageous conditions. For example, in Mexico’s four poorest states, I have observed that some children attending indigenous and small community primary schools have levels of achievement higher than most of their urban counterparts in standardized mathematics and Spanish tests. This demonstrates that poor children are capable of the same levels of performance as their non-poor counterparts. I have found the same overlap in the levels of academic achievement among secondary school students in rural and urban areas in Colombia. Variations in student achievement can be explained by differences between schools and by differences between children. The data from Mexico show that poorer the child, the more important the quality of the school in explaining the differences in academic achievement. This finding is consistent with research in the United States and other OECD countries, but it is especially significant because it signals the potential of schools to further opportunity for the poor to learn.

Several Latin American governments are implementing policies to foster educational opportunities for poor children. These programs include affordable access to pre-school in disadvantaged communities, improvement of educational quality in rural areas, and improvement of the quality of education in selected schools attended by disadvantaged children in urban and rural areas. Several years ago, for example, Chile started a program to improve the quality of rural schools and to proactively compensate by upgrading schools attended by the poorest children. Mexico has several programs to selectively increase the quality of education of the schools in its poorest states and those attended by the poorest children. There is much yet to learn about the effects of these interventions, although they signal the possibility to implement compensatory and positive discrimination policies.

Turning around the vicious cycle of poverty reproducing itself through the education system requires that we better understand and change the conditions that give opportunities to learn to the children born in low-income homes. We must look at the experience of Latin America and other regions to evaluate the results of policies to provide the children of the poor real opportunities to learn and to experience social mobility. The Summit of the Americas last year prioritized education as an avenue of poverty alleviation. Achieving this goal will require education reforms which actually implement these policy aspirations. Only then will it become possible for every citizen in the region, including the 168,787,800 people-most of them children-now living on less than $2 a day, to benefit from the remarkable economic, social and political achievements made by Latin America during the twentieth century.

Spring 1999

Fernando Reimers is an Associate Professor at the Harvard School of Education and Director of the new masters program in international education policy. He obtained his masters and doctorate in education policy at Harvard and his Licenciatura at the Universidad Central de Venezuela where he lectured 16 years ago. Prior to joining the Harvard faculty he served as senior education specialist at the World Bank and as an advisor to several governments in Latin America on issues of education reform. He is currently conducting research on the links between education and poverty in Latin America.

Related Articles

Gender and Education

In terms of sheer numbers, girls in Latin American schools aren’t in such bad shape compared to other areas of the world. They have gained what is termed “gender parity”-girls are as likely as…

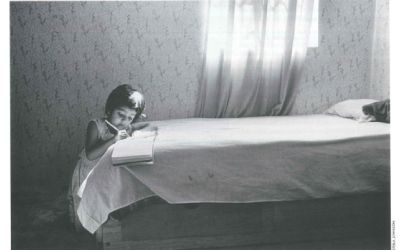

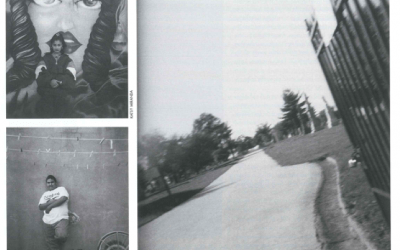

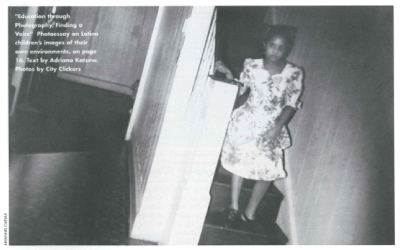

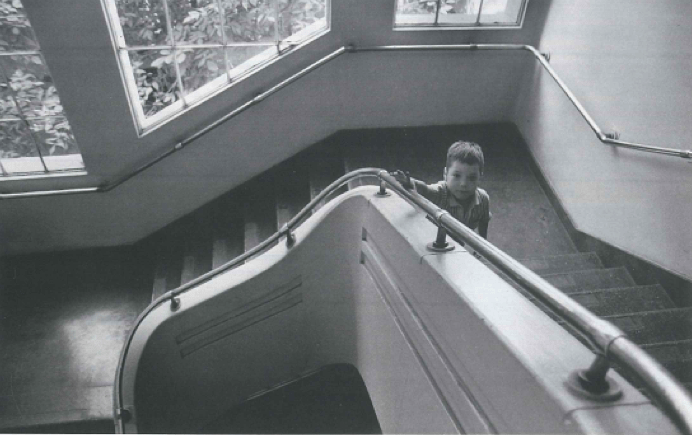

Education Through Photography

From 1995 to 1997, more than 80 Latino children in Philadelphia’s barrio participated in City Clickers, a photography and creative writing program that I created and implemented with the…

Education in Latin America

Whenever one asks about ways of struggling against impossible odds in Latin America, one is told not to worry because no”hay mal que dure cien anos” (no evil lasts one hundred years). The…