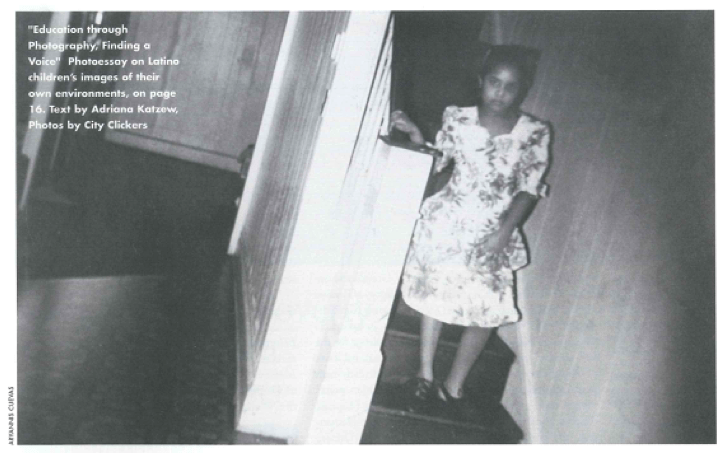

Education in Latin America

Challenges for Latin Americans, U.S. Latinos

Whenever one asks about ways of struggling against impossible odds in Latin America, one is told not to worry because no”hay mal que dure cien anos” (no evil lasts one hundred years). The saying points in the direction of passive resistance since all one needs to do is wait for evil to pass. Remembering our collective histories of endurance in Latin America, Central America and the Caribbean, one may relax and choose to wait it out. But the popular saying has a second part to it. After telling you that “no hay mal que dure cien aíños,” the saying continues, “ni cuerpo que lo resista” (nor body that can resist it). This second part points in the direction of shifting the form of resistance from passive to active since, clearly, resisting for so long is not possible.

This issue of DRCLAS News, which focuses on education, challenges this popular saying. It inspires active resistance to the educational neglect suffered by the majority of Latin America’s citizens. As Fernando Reimers in “Education and Poverty in Latin America” tells us, in Latin America “[i]t is almost possible to imagine two distinct countries within each country’s physical borders, according to educational attainment.” He explains that the first country prepares students for participation in the elite, while the second country, inhabited by the dispossessed, receives few educational opportunities, insuring their perennial poverty.

The second country has tested the saying and found it fundamentally flawed: their educational neglect can and has lasted for hundreds of years. Poor and indigenous people in Latin American have resisted with their bodies, minds and spirits, but change has eluded them. They cannot wait any longer.

There is general consensus that if the countries of Latin America were serious about facing up to the poverty of millions of children, they would focus on educational reform. Students and parents know this; some politicians and policy makers seem to understand it. Yet, all too often, one finds an absence of will (and capacity) to implement changes and provide the necessary supports to ensure success. Merino Juárez, in his essay, “Education Decentralization and Institutional Change: Preliminary Lessons from Mexico,” concludes that “absent additional reforms, the process might be too slow.” Given how long poor and indigenous children have waited so far, “too slow” is too long. The cost for each generation that is left waiting–the unrelenting continuation of poverty–is too high.

Links explored in this edition–especially those that connect the experiences of Latinos/as in the northern and southern hemispheres–deserve further scrutiny. Donaldo Macedo, in the foreword to Paulo Freire’s book Pedagogy of Freedom(1998), explains that the United States is starting to resemble the Third World. Rodolfo Stavenhagen in his article, “Society and Education: Latin America’s Challenge for the 21st century,” after pointing to the poor educational levels of indigenous children in Latin America, particularly high school desertion rates, reaffirms Macedo’s observation, pointing out that “a similar situation prevails among Hispanic children in parts of the United States.” Lawrence Hernandez, in “Latino Families and the Educational Dream: Resilience Along the Rocky Road,” and June Carolyn Erlick, in “Harvard Immigration Project: Researching the Lives of Children,” explore these connections in more detail. Hernandez explains that “Latino immigrants have the worst performance and the grimmest economic prospects in young adulthood of any groups.” The Harvard Immigration Project, directed by Marcelo and Carola Suarez Orozco, finds that “many successive generations of youths from immigrant backgrounds are performing more poorly than their foreign-born, first generation peers.”

Again, as if to test the popular saying, poor Latinos in the United States searching for better educational and economic opportunities for their children come up empty handed. Evil not only seems to last for hundreds of years, but it also seems to follow parents and children to the United States. But Latinos/as are resisting, searching for solutions to a centuries-old problem.

This issue of DRCLAS NEWS offers up examples of new solutions to old problems. Stavenhagen points to the necessity of community involvement: “educational systems will flounder without community support and they will flourish with community involvement.” Lúcia Dellangnelo, in “Community Participation: What Do Communities Get Out of It,” adds to Stavenhagen’s argument, explaining how participation in the schools benefits community members in multiple ways. Through activism, individuals and families break their isolation, reconnect with their communities, and find strength in the collective struggle to improve the lives of their children. Claudia Uribe, in “The Teacher and School Incentives Program in Columbia: Promoting Participation for Improving School Quality,” finds hope in the community and recounts her visits to schools where everyone had mobilized to paint, raise funds, and plant gardens. Full of hope and excitement, these communities view these activities as steps in the right direction.

From these articles, communities emerge as powerful agents in educational reform. It appears that the most effective way to break the cycle of poverty is to invest time, effort, and resources in community activists who are unwilling to wait another one hundred years for change. To effectively support community-change efforts, however, we must shift our paradigm. The paradigm that rules our way of thinking both in Latin America and the United States–that educational/social change comes from the top down–prevents us from understanding that effective change, in fact, comes from the bottom up, or at the very least, emerges from collaborations at the grassroots level. It will take a leap of courage and conviction to shift paradigms, but the cost of not doing so is too high–continued poverty for millions of Latinos/as throughout the Americas. Finding ways that we as educators begin to learn from those we have unsuccessfully tried to educate for hundreds of years is the only strategy that makes ethical, moral and common sense.

The following articles explore ways in which new hope can be discovered in the midst of old stories of neglect and despair.

Spring 1999

Eileen de los Reyes, a political scientist, is an Assistant Professor of Education in Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. She is interested in issues of power and the creation of democratic communities in both formal and informal education. Her forthcoming book, Pockets of Hope: How Students and Teachers Change the World, studies the process through which marginalized students educated in democratic classrooms, emerge as powerful agents of change in their schools, communities and the society at large.

Related Articles

Latino Families and the Educational Dream

Insisting that we do our interview in English, Ricardo Robles reluctantly recalls the dreams he had for his children when first arriving nine years ago to the U.S. from Zacatecas, Mexico.” They…

LASPAU Expands Fulbright Partnerships

LASPAU Expands Fulbright Partnerships An Array of Partners Since 1975, LASPAU has administered Fulbright Program grants for Latin American and Caribbean faculty members, professionals, and researchers. Fulbright programs have provided academic opportunities for...

Harvard Immigration Project

A refrigerator is the most important thing in life, the 10-year-old immigrant child reported in a matter-of-fact sort of way…