About the Author

Alfredo Garcia Garza is a Ph.D. student in the Committee on the Study of Religion at Harvard University.

El Niño Fidencio

Healing Power of the Afflicted

A few years ago, during my first semester at Harvard Divinity School (HDS), I was shocked when Professor Davíd Carrasco lectured about his research on the transnational Mexican curandero (spiritual healer), el Niño Fidencio—José Fidencio de Jesús Síntora Constantino (1898-1938). Up until that moment, I had largely kept my own childhood years of attending Fidencio’s healing rites in rural México, a private matter. I was afraid how people would react if I told them I grew up going to curaciones (healing rituals), where a materia (medium) channeled the spirit of a dead Mexican curandero, so I kept those religious experiences to myself.

To my surprise, I learned that Carrasco had actually met el Niño (or simply Fidencio) while he was a graduate student at the University of Chicago in the 1970s. He was part of a misión (healing community) located in Little Village, a Mexican neighborhood in Chicago, at the same time he was studying shamanic traditions with the historians of religions Charles H. Long and Mircea Eliade. As I came to understand the vast impact of el Niño, I realized that my own religious experiences and practices could be utilized as an unprecedented source for organizing new knowledge about the sacred. That is, new knowledge about what Eliade in The Sacred and The Profane called, “pre-eminently the real, at once power, efficacity, the source of life and fecundity… (which) reveals absolute reality and at the same times makes orientation possible.”

In “el Rancho”—a little rural town in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila—,where I grew up, every third day of the month people came together to meet the sacred. They would come from surrounding ejidos (agricultural towns) to attend curaciones organized by the local misión. The scent of sahumerio (burning incense) could be smelled blocks away, foreshadowing the curación about to begin. The gathering took place at night, in the home of the materia who channeled the spirit of Fidencio. Most of those organizing the séance and attending it were women—whose ‘folk religious practices (like Fidencio himself) have been discouraged or prohibited’ by the Catholic Church, anthropologist Kay Turner notes.

The curación started by the women praying the rosary behind the materia, who in turn, was facing the domestic altar. The altar was filled with candles and images of the crucified Christ, the Virgen de Guadalupe, other saints, and Fidencio (who is recognized as a saint only by his followers). As the rosary came to an end, the materia started yawning. This was the signal that he was about to enter a trance. One of his main assistants covered his head with a towel as the materia’s yawning turned into accelerated coughing and el Niño took possession of his body. Then, Fidencio softly recited three Ave Marias in call and response form, marking the end of the ecstatic transition.

As el Niño Fidencio manifested himself, he greeted everyone and led them in reciting different prayers. One of the initial prayers used to announce his presence blessed “el presente y el ausente,” and believers and non-believers alike, as well as those addicted to alcohol (el borrachito) and those in prison. In other words, el Niño started curaciones by blessing the marginalized—those neglected, shamed, and persecuted by political or religious institutions.

Fidencio blessed those who were present as well those who were absent. The absent were those in el otro lado, namely men who had migrated to the United States; many of them were the husbands and fathers of the women and children attending curaciones. El Niño was a spiritual caregiver to those families separated by the border.

Sitting or standing for hours, people waited in line for a personal, customized, one-on-one consultation with their confidant. The time varied depending on the amount of people attending and on the number of migrants who kept the phone ringing. They were calling from different parts of Texas so they could share their pains and afflictions and hear Fidencio’s irreplaceable counsel.

El Niño gave those attending and calling recetas (“prescriptions”) of medicinal herbs for their ailments. He cured empacho (stomach discomfort) and mal de ojo (evil eye). He did barridas or limpias (sweepings or cleansings) using pirul (pepper tree branches) to cure susto (soul loss/fright sickness) resulting from traumatic experiences. Most importantly, he advised his followers to wait, or disclosed the pivotal moment to act, when making life changing decisions or responding to a tragedy regarding their families located in México, in the United States and even in Central America.

As the curación went on and the line of people waiting to see Fidencio kept growing, they received food prepared by las cocineras—members of the misión whose role was feeding those attending the healing ritual. El Niño did not charge anything to those seeking to be healed. Instead, he gave away everything they reciprocated. As a kid, I played a role when el Niño share ofrendas (offerings) during curaciones.

He often called for me to give me a task. Even though I was not the only kid being called, I was the only boy whom he referred to as “el intelectual,” suggesting that I preferred solitude to immerse myself in my studies, or perhaps he simply applied humor to the fact that I wore glasses. Regardless, many years later Fidencio revealed to me that he had “sent” me to Harvard, which I interpreted—in part—as him watching over me and accompanying me in my academic journey.

When called by Fidencio during curaciones, I skipped the whole line from wherever I was sitting with my mother to see what was required of me. “Dales una naranja” or “dales un dulce” he said. I carefully grabbed the bag of fruits or chocolates and went through the line distributing them one by one. I noticed some of the chocolate bags had English labels, indicating that they were sent by some of his followers in the United States. When not occupied with receiving gifts (food, fruit, candy, or blessed crafts) from El Niño, those waiting to see him kept singing alabanzas.

Alabanzas are religious hymns central to curaciones. Across time and space, ordinary people have written them to express their religious experiences as followers of Fidencio. The alabanzas mention places like San Antonio, Texas and Chicago, Illinois, where misiones organize curaciones for their materia to channel the spirit of el Niño Fidencio.

Anthropologist Antonio N. Zavaleta, who has carried out a 30-year academic study of Fidencio and his followers, notes that there are misiones at places such as Saltillo and Torreón in the state of Coahuila, in Monterrey in the state Nuevo León, and Reynosa and Matamoros in the state of Tamaulipas. The three states are consecutively adjacent to each other. In the book chapter “El Niño Fidencio and the Fidencistas,” Zavaleta also notes that misiones in the United States developed in “areas where Mexican migratory agricultural workers settled, such as Texas, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Colorado, Washington and Oregon.”

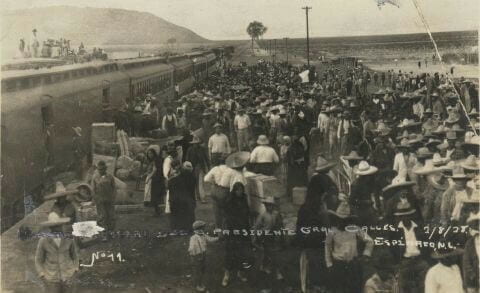

Like the multitudes of people who arrived in train to Espinazo, Plutarco Elías Calles (México’s president) sought Fidencio’s healing in 1928. Photo source: Dr. Antonio N. Zavaleta’s El Niño Fidencio Research webiste. https://drtonyzavaleta.com/category/el-nino-fidencio-research/

The (peripheral) center in the alabanzas is a tiny town of the desert called Espinazo. It originated as a railway station located in the outskirts of the states of Nuevo León and Coahuila (a few hours away from el Rancho). Espinazo became known as “el campo del dolor” (the field of pain) and a site of pilgrimage since el Niño Fidencio rose in influence and fame in the late 1920s, when thousands of desperate people came in seek of healing. Espinazo is referred to in dozens (if not hundreds) of alabanzas.

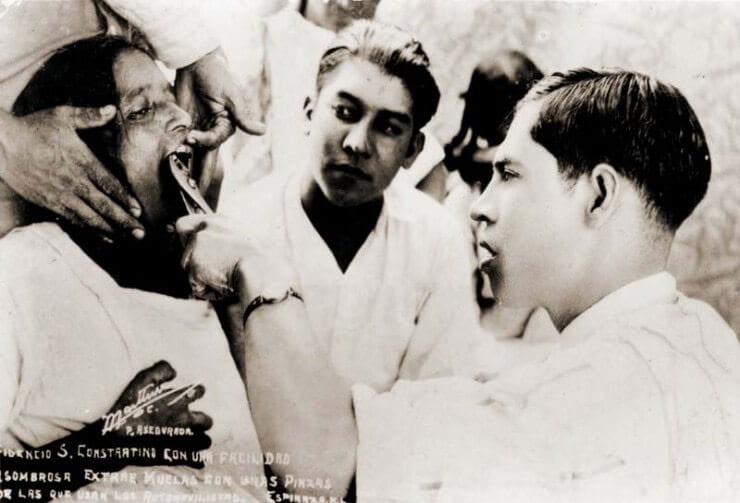

Taken together, the alabanzas may be understood as a sacred history narrating the miracles and marvelous acts performed by the God-chosen illiterate healer of the desert. They speak of the primordial times when Fidencio—walking barefoot among the poor in Espinazo and without any medical training—performed surgeries, removed tumors, cured lepers and the mentally ill.

Fidencio extracts a malignant tumor using a piece of glass. The surgery is performed without anesthesia. Photo source: Dr. Antonio N. Zavaleta’s El Niño Fidencio Research website. https://drtonyzavaleta.com/category/el-nino-fidencio-research/

The alabanzas include witness accounts of Fidencio’s power and unconventional healing methods in making the blind see and the mute speak. They mention his use of medicinal plants and the significance of el pirulito, the pepper tree under which God gave the don (gift of healing) to Fidencio and revealed to him his mission on earth. Simply put, Fidencio’s mission is to use his don to heal the suffering poor. Thus, the alabanzas conceive Espinazo as holy ground, a space that became sacralized through a manifestation of the sacred—that is, through a “hierophany.” Essentially, what the alabanzas have in common is that they reveal—what Eliade calls—an encounter with the sacred.

Fidencio, “easily” and “extraordinarily,” extracts teeth using pliers. Photo source: Dr. Antonio N. Zavaleta’s El Niño Fidencio Research website. https://drtonyzavaleta.com/category/el-nino-fidencio-research/

A favorite alabanza I heard while growing up is called “A tus pies vamos llegando” (we are arriving at your feet). It speaks of an afflicted community that cries as it arrives at Fidencio’s feet in el campo del dolor—the field of pain. According to the alabanza, this community gathers around their great, God-chosen, Mexican doctor and saint who heals the ailments of the poor. The reference to Fidencio’s God-given abilities as a doctor is significant because it implies his lack of medical training and formal education whatsoever. “A tus pies vamos llegando” also highlights the gratitude the faithful feel towards God for allowing them to arrive near el Niño—in whom they put their “trust” and “hope”—, for “everyone” knows God heals through Fidencio. Therefore, they long to be in the company of Fidencio as he “imitates” the divine savior—also a healer of the poor in his own biblical times. The alabanza ends by recognizing Guadalupe—“our mother”—as el Niño’s protector and asking Fidencio for a blessing before they depart.

Something to be learned from this alabanza is that the afflicted community arriving at Fidencio’s feet suggests a sense of orientation toward a transcendental power. The implication (found explicitly in other alabanzas) is that they experienced a transformation in their being through an encounter with the sacred.

The encounter with the sacred is also revealed in the way people greet Fidencio. As they approach him one-on-one, most people kiss the hand of the materia channeling his spirit (the materia may be male or female depending on the misión). I have noticed that newcomers attending curaciones do not usually kiss Fidencio’s hand (unless instructed by others to do so). Kissing el Niño’s hand, or “paying him respect,” is a subtle way to differentiate between those who feel a sense of reciprocal obligation to Fidencio and those whose “heart” has yet to be transformed.

For instance, in a short VICE investigative film called The Miraculous Life of El Niño Fidencio (2015), a reporter meets David Donado—the main materia in Espinazo. The reporter approaches el Niño and says he came to conocerlo (know who Fidencio is). Then he gets closer and kisses the crucifix in the materia’s hand. El Niño responds with a hint of humor (addressing him through the formal and respectful usted), “(because you have seen me) you think you know me? You won’t know who I am until I touch your heart.” Meaning, he will not know who Fidencio is until he experiences a transformation in his being.

In other words, without encountering him as the sacred one cannot know Fidencio. Therefore, kissing el Niño’s hand implies and reveals a reciprocal relationship with the sacred. Another thing this film highlights for me is a fundamental distinction between some of Fidencio’s followers in Espinazo and in el Rancho. In my hometown, Fidencio’s followers may not necessarily conceive themselves as members of a Fidencio’s organized church or larger movement, but simply as Catholics who also are followers of Fidencio. Regardless of affiliation, the transformation in one’s being implies a change in how one conceives suffering.

Whether physically healed or not, Fidencio’s followers remain loyal to him, notes writer Carlos Monsiváis in his book, Mexican Postcards. ‘Through their faith they transform imposed suffering into joyful suffering.’ That is, they experience healing at a deeper spiritual level by assuming—what Eliade calls—a different existential mode of being in the world. A mode of being where—through Fidencio—the afflicted make suffering in their lives bearable.

Overall, this not to ignore the socioeconomic and transnational neoliberal forces that create miserable living conditions in the first place. Rather, I am noting that despite economic exploitation and political subjugation, despite cultural vanquishment and social destitution, through the sacred the poor may endure structural violence and postpone death. By creating the conditions for the sacred to manifest himself, healing communities play a crucial role in (re-)orienting and giving meaning to the afflicted. To this day, in the U.S.-México borderlands and beyond, Fidencio’s followers form misiones to deal with their families’ suffering created by migration and deportation. The afflicted continue to trust in a Mexican curandero who, in life and in death, has been a source of healing power in their lives.

More Student Views

Resilience of the Human Spirit: Seizing Every Moment

In the heart of Chicago, where I grew up, amidst the towering shadows of adversity, the lingering shadows of generational demons and the aroma of temptation, the key to the gateway of resilience and determination was inherited. The streets of my childhood neighborhood became, for many, prisons of poverty, plundering, crime and poor opportunity.

Andean Cultural Landscapes in Danger: The Chinchero International Airport

English + Español

Cusco stands as one of the most culturally and ecologically captivating regions globally.

Blossoming Bonds: Beauty and Belonging in Mexico

When I heard the news about my upcoming trip to Mexico, a surge of excitement coursed through me, and I immediately felt the urge to share this exhilarating news with my close friends and family.