A Review of El Salvador Could Be Like That: A Memoir of War, Politics, and Journalism from the Front Row of the Last Bloody Conflict of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War

Writing the Rough Draft of Salvadoran History

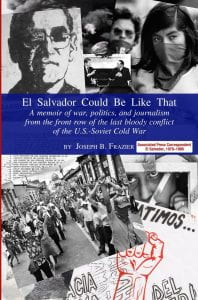

El Salvador Could Be Like That: A Memoir of War, Politics, and Journalism from the Front Row of the Last Bloody Conflict of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War by Joseph B. Frazier (Karina Library Press, 203 pages)

“There are no just wars. There are only just causes.”

I was sitting in the modest home of a former FMLN guerrilla woman in a rural village in the northeastern corner of El Salvador. It was 2001, and I was nearing the end of my second year-long stint in this small Central American nation, interviewing more than 200 Salvadorans, mostly from rural areas, about their experiences during the civil conflict of the 1980s. My host was not one of my campesina respondents, but rather a highly educated woman with urban, middle-class roots. She was small but wiry; an aura of relaxed self-assurance veiled, but could not hide, the underlying sinewy toughness of her personality. She had struck up a friendly conversation with my friend and me as we wandered through her village. Within minutes of saying hello, the former guerrillera had invited us to spend the night in her extra bed. After two years of consistently generous hospitality from rural Salvadorans, I had ceased to be surprised by such offers. We graciously accepted.

After dinner, our host’s story began to unfold. A university student turned activist turned rebel fighter in the late 1970s, she had spent 12 years fighting with the FMLN guerrillas in the rural war zones, and then elected to stay in the countryside after the Peace Accords were signed in 1992. Her story surprised me on two fronts. For one thing, in my experience, most urbanites had been only too happy to return to city comforts after the war’s end. For another, she made a number of statements suggesting that she thought the FMLN’s militant actions in the early 1980s might have been a mistake. It wasn’t that most of my respondents were knee-jerk FMLN supporters. Most expressed frustration with at least some aspect of party politics, even if they at the end of the day preferred the FMLN to other parties. But none—not one—had ever questioned that war was the FMLN’s only option in 1980s El Salvador. The state military was massacring Salvadoran civilians, I was told. The FMLN had no choice but to pick up arms and defend them. After another such moment of questioning the FMLN’s militant strategy, I asked, “But didn’t you think the war was just?” To which she responded: “There are no just wars. There are only just causes.”

Joe Frazier would have felt right at home in that conversation.

Frazier’s book takes us back to El Salvador in the early 1980s, where thousands were killed, tortured and disappeared each month because they expressed the wrong political beliefs, lived in the wrong village, exchanged pleasantries with the wrong friends, or just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Frazier, a foreign correspondent for the Associated Press living and working in wartorn El Salvador recounts the war in a dizzying fashion. His writing is clear and direct, slipping seamlessly from anecdote to interview to colorful jokes to political commentary, but often losing track of dates, places or the significance of the reported event. Indeed, Frazier seems to be nudging us to draw exactly this conclusion: that the events themselves were insignificant; what mattered were the lives lost in exchange for the political posturings of the 1980s.

This is a memoir, not academic analysis. As I read, I initially found myself somewhat frustrated at the flatness of the Salvadoran people portrayed in the book. But soon I realized that this was intentional. Frazier wants us to feel his frustration with the flatness of his own interactions with Salvadorans in a situation where so many more powerful emotions—outrage, anger, deep sadness—would have seemed more appropriate. For example, Frazier recollects how well-meaning AP editors repeatedly asked him to get the opinions of the “regular” Salvadorans on the street, despite reminders that “regular” Salvadorans were far too smart to vocalize their opinions to a U.S. reporter if they wanted to avoid torture and death.

By the book’s end, the eclectic and dizzying collection of recollected events began to take on a rhythm of its own, and the feel of El Salvador in the 1980s—an El Salvador I’ve never experienced—began to emerge. This was a time when Salvadorans survived by saying the exactly right nothing. Where is your compañero? Working. Doing what? Working. Where are the other men in this village? Working. This was a time when politicians offered platitudes and excuses, but no real information about the fighting, the deaths, the armaments, or the intelligence that made widespread killing possible. And the greatest silence of all came from the bodies, the relentlessly accumulating bodies, whose appearance on busy sidewalks, along highways, or at the foot of the infamous “Puerto del Diablo” cliffs was so routine that they seldom caused passersby to slow their pace. These bodies are regularly remembered throughout Frazier’s manuscript.

Reading this book helped me understand the magnitude of the challenges faced by journalists in war zones. They are asked to write a story, to define the sides of a conflict, to explain the bodies, to provide accurate accounts of where arms came from or which political alliances were forming, in a situation where such information could (and did) get you killed. It is because of reporters like Frazier that the international community learned about massacres like El Mozote and the Rio Sumpul. It is because of reporters like Frazier that the international community came to understand how “democratic” elections can exist alongside antidemocratic politics. It is because of reporters like Frazier that the international human rights community turned its attention to Central America, at least for a while, placing pressure on the warring sides to significantly reduce the massacre of civilians by the second half of the war, and to help forge a peace agreement by 1992.

Frazier is at his best when he is reflecting about the past. This richness is developed through interviews with hard-to-kill communist leaders, gringo surfers and war orphans. His discussion of the complicated relationship between the Church, the state, art, and the people expertly captured the complexity of political ideas, and the pervasiveness of old power, in El Salvador. Frazier’s discussion of the present is understandably less well-developed and tinged with sadness. He draws striking comparisons between deaths caused by gang violence today with those caused by political violence in the 1980s. He laments the continued poverty and suffering of Salvadorans, as well as the state’s efforts to forget the past, including wiping the nuances of the civil war out of school children’s history books. Mostly, he laments how little the rest of the world seems to care about the continued poverty and violence that wracks El Salvador, after paying so much lethal attention to it in the 1980s.

Frazier never had the luxury of getting to know Salvadorans’ opinions about the war like I did—through long, leisurely conversations that lasted into the dark of the night. And yet he sacrificed so much to tell the story of Central America. While in El Salvador, Frazier’s friends and fellow journalists were killed. His wife was killed. Several people who granted him interviews were killed shortly after speaking to him. Yet he stayed on, raising his young son. It is difficult to overstate his commitment to the Salvadoran people, despite the understated nature of his memoirs.

Upon finishing the book, what most struck me was the difference between his Salvadoran experiences and my own. Journalists like Frazier wrote the rough draft of Salvadoran history, often at great personal risk. Since then, forensic scientists have uncovered bodies, former generals have begun to confess their war crimes under new amnesty laws, and academics have started putting flesh on the skeleton of Salvadoran history. I, like Frazier and my Salvadoran host, agree that there are no just wars. But I could have never written about the devastation of the Salvadoran war as did Frazier, who actually lived it. Nevertheless, the fact that Salvadorans are now free to fill in the details of Salvadoran history with data from their own lives, either through their own writing or through long interviews with visiting academics, is, in my view, reason for optimism.

Jocelyn Viterna is Associate Professor of Sociology at Harvard University. Her book, Women in War: The Micro-processes of Mobilization in El Salvador will be published in 2013 by the Oxford University Press.

Related Articles

First Take: Memories and Their Consequences

I visited the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos in Santiago, Chile, two years ago. It was a heart-rending experience. To enter the museum, I moved through a stark and subterranean passage and found myself in a somber space of transition. There, a wall of photographs transported me back in time—long ago in a messy graduate student lounge in Cambridge, Massachusetts, four of us stood in shock …

An Exploration of the Mexican Health Care System

The recent creation of Seguro Popular—a governmental program granting basic health services to millions of Mexicans previously uninsured—has newly enabled thousands of Mexican women afflicted with breast cancer to access treatment. With the growing prevalence of breast cancer survivors, the question now arises of how best to maintain their health and address their needs. …

Educating the “Good Citizen”: Memory in postwar Guatemala

On my many field trips, I tell Guatemalan teens I’m interested in how they learn about the 36-year conflicto armado (armed conflict). I then study their faces. If not baffled, they avert their eyes and share refrains passed on by many adults in their lives: “We have no historical memory,” or “In Guatemala, there is no historical consciousness.” School teachers say, occasionally with concern, “We don’t talk about that here,” …