El Salvador’s Future

A Pending Quest for Social Justice and Equality

In 2005, I met María Chicas. The gaze of this young woman reflected the harshness of her life in Torola, one of the poorest municipalities of Morazán. For the first time in her life she had become a beneficiary of the government-run poverty alleviation program aimed at women and their families. Chicas and her family were participating in Red Solidaria, a conditional cash transfer program (CCTs), and the first program targeted to the poorest families in rural areas in El Salvador. The design of Red Solidaria (now Comunidades Solidarias) was based on the best practices and evidence-based results of Bolsa Familia (Brazil), Oportunidades (Mexico) and Familias en Acción (Colombia).

Like the majority of participants in the 32 poorest municipalities, at first María Chicas did not believe in the truthfulness of the program. Nevertheless the applicants went through the motions, took the interviews and then signed the participation and responsibility agreement. In the short term, the program emphasizes poverty alleviation through cash transfer, an amount sufficient to ensure the participants’ regular school attendance and health checkups. In the long term, the objective of the program is human capital accumulation.

For me, women and men are equal, and I’ve educated my husband this way. … Because I have a head (own thinking) and I can also decide … this is what I’ve learned in the program.

—María Chicas, Caserío Agua Zarcas,

The program has had a positive impact on education and health, as well as empowering and increasing the self-confidence of women through its training component, according to the impact assessment conducted by FUSADES and IFPRI between 2007 and 2010. This positive impact demonstrated by these programs in Latin America, along with the development of policy instruments, created an opportunity for promoting and strengthening social protection systems in various Latin American and Caribbean countries—policies that are both effective and aimed at achieving sustainable human development.

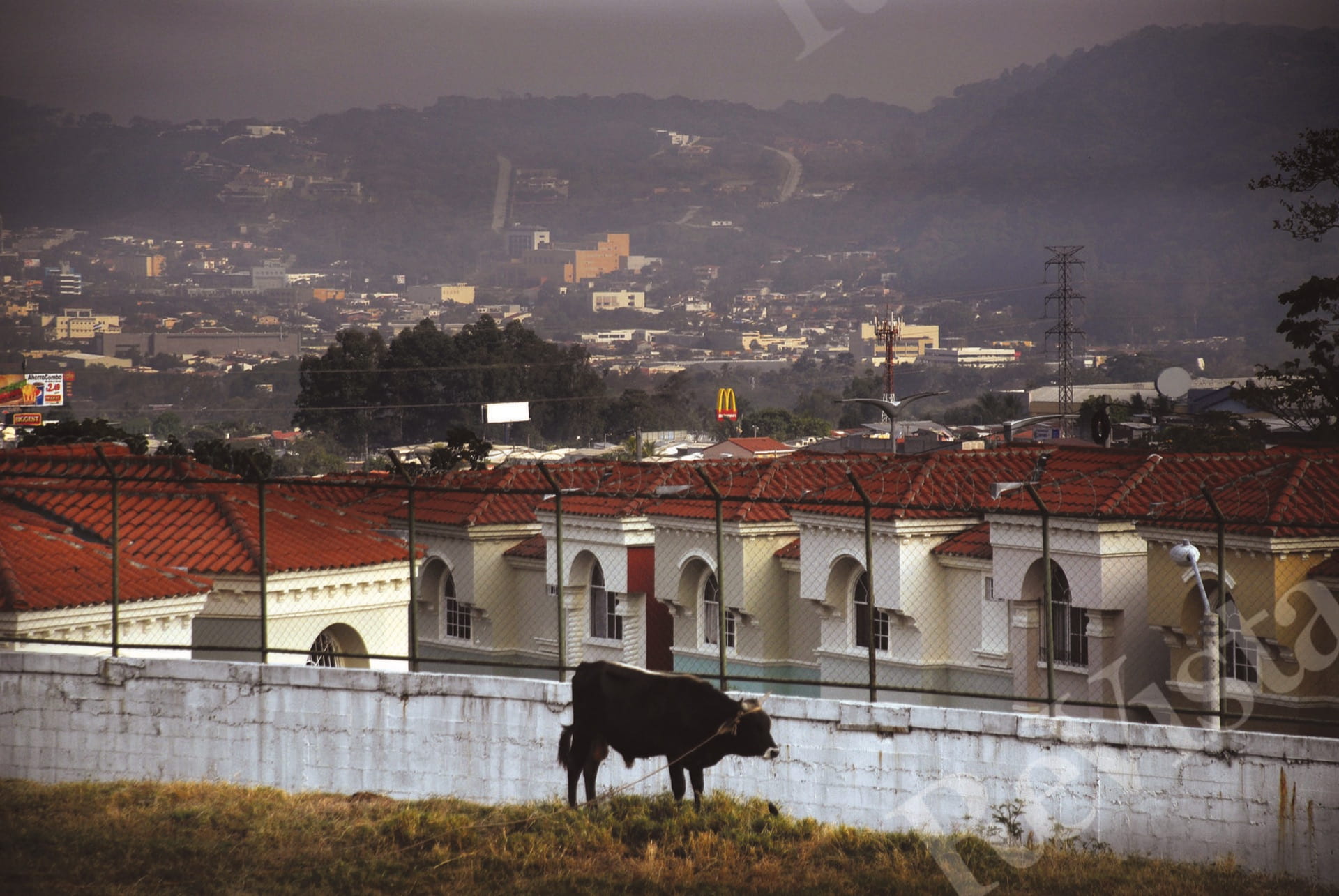

Twenty-four years after the signing of the Peace Accords, social justice and equality is a pending quest in El Salvador. The twelve-year civil war tore apart the social fabric and eroded social cohesion in this small country of Central America. However, it is important to recall that inequalities and high levels of human poverty were key reasons for the war.

There have been five democratic elections since the war ended that have included the FMLN as a political party, resulting in three consecutive right-wing governments of the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) (1994, 1999 and 2004) and two left-wing governments of Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) (2009 and 2014), thus providing political alternation. These governments have undertaken economic and social reforms in a complex political scenario, characterized by increased polarization and systematic political confrontation between ARENA and the FMLN. They have shaped the way the country faces the challenges of good governance, building and strengthening public institutions and sound public policies that address the main social, economic and environmental issues, and all of these in the context of globalization. This article focuses on the social dimension of public policy and reforms.

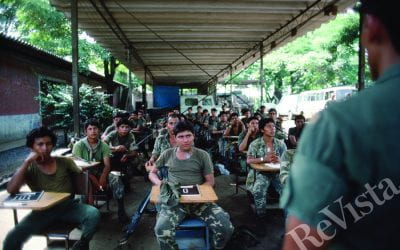

Social policies during the first twelve years of the post-conflict period in El Salvador were strongly influenced by the structural adjustment programs and liberalization reforms known as the Washington Consensus. An important reform in social security was the shift of a pay-as-you-go pension scheme to individual retirement accounts privately managed by the Pension Fund Administrators after the Chilean model. This 1998 reform sought to lighten the fiscal stronghold that the old system had on public finances. Nevertheless, the transition costs of the reform remain a fiscal burden; very low coverage of the population (20 percent) has not improved; multiple systems coexist (i.e. Armed Forces), and the economy contains an extensive informal labor market which, according to the International Labour Organization, encompasses 65 percent of the active population. The political debate about social security and pension systems, of problems such as fragmentation, low coverage and lack of sustainability, continues to be postponed.

Other social reforms have focused on primary education and health and basic infrastructure, redirecting public spending towards services that help the poor. In 1991 the government implemented EDUCO, a decentralized community-oriented strategy that reached the poorest rural communities of the country; this helped expand six-fold the coverage of primary education in five years. Education reforms (i.e. curricular) were carried out between 1995 and 2004, and a long-term National Education Plan for the 2005-2021 period, the result of a national consultation process, was put in place. In 2015, the country achieved the educational Millennium Development Goal of universal primary education. The most urgent challenge now is to ensure the physical safety of students and teachers in schools, and to achieve quality education, as well as longer-term pre-school and secondary-school coverage.

The health-care system has been characterized as being highly centralized and fragmented; a public sector brings together different health-care service schemes—for the general population, for teachers and armed forces, among others. The Ministry of Public Health now covers eight out of every ten Salvadorans in the country; the Social Security Institute covers the formal sector workers, among other entities. In 2009 the National Health Reform was launched. Its goal was to achieve equality and universal access to health-care services, based on a primary care approach, as well as the promotion of social and community involvement. However, this reform must overcome the existing institutional weakness. Although the process of change has been implemented at a slower pace than planned, it has contributed to the improvement of key indicators, such as the reduction of maternal mortality.

Despite these modest but important advances in education and health, these sectors faced very limited—below the Latin American average—budget allocations. In El Salvador, the public social expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 2012 was 14.8 percent. Education and health averaged 4 percent each. Social protection expenditure as a percentage of GDP was a paltry 4.8 percent (El Salvador government data).

Poverty and inequality persist as a common denominator in El Salvador, as well as in other countries of Latin American and the Caribbean. We need to put a human face to the more than 35 percent of families living in multidimensional poverty in El Salvador. The Garcías, the Riveras, the Mejías face a variety of hardships like the following: eight out of ten of these families live in crowded conditions, face underemployment and job instability and have no access to sanitation; three out of ten of their children do not attend school and six in every ten are fearful of attending school because of insecurity (Multidimensional Poverty Measure, government and United Nations Development Programme).

While other Latin American countries began expanding social assistance programs to cover a segment of the population excluded from formal social security net years ago, El Salvador did not implement its first targeted program designed to alleviate poverty, Red Solidaria, until 2004. The impact assessment and the program’s positive results encouraged the new left-wing government to maintain the program. The program incorporates rigorous design, implementation and accountability, based on several management tools: targeting mechanisms (geographic and individual), registry of beneficiaries, information systems and monitoring and evaluation. This system served as a model for the Social Protection Universal System launched by the government in 2009.

The Social Protection Universal System gained further legal support in a broader law passed in 2014. This Development and Social Protection Law establishes a system that protects, promotes and ensures compliance with the basic rights of the individuals. The system also establishes criteria for targeting the poor and vulnerable population and expanding the programs. Instead of defining target groups or individuals according to parameters of vulnerability, poverty and exclusion, the law lists programs, many of them without impact assessment, casting doubts about their effectiveness. Another weakness is the absence of a strong institutional architecture to ensure its effective implementation. A third drawback of the law, and a serious one, concerns the lack of clear funding provisions, as no percentages or fixed monetary resources were set by the legislators.

Despite all these efforts at designing laws, policies and programs, the government’s capability to meet the goals of poverty reduction and social exclusion has fallen short. The results of the Multidimensional Poverty Measurement presented by the government and the United Nations Development Programme in 2014 are a clear indication of this situation.

Social protection can and should contribute to inclusive economic growth through investment in the workforce, with a particular focus on socially disadvantaged groups, expanding their chances of entering the labor market in equal conditions. Greater investment in health and education will also enhance opportunities among the more vulnerable, while aiming at sustainable and equitable growth that in the long run will reduce poverty and the need for social assistance.

Institution-strengthening, long-term consistency of social policy implementation and the factoring in of external shocks—such as instability in the price of commodities and the effect of natural disasters—must be considered in the efforts to speed up the implementation of sound social policies that will shorten the path towards development. In the case of El Salvador, the context of political and social violence, past and present, has an important impact that has to be taken into account. While people like María Chicas from Torola and her children have benefited from social protection programs, they should also have the opportunity to generate their own income and live a sustainable life with dignity and full rights.

The challenge in El Salvador is to craft a country-oriented vision of development shared by all. Most importantly, we need to place people squarely at the center of the development process. The economic reforms for a sustainable and equitable growth must aim at improving productivity and widening economic opportunities, particularly for young people entering the labor market for the first time. Last but not least, progressive fiscal and taxation policies should contribute not only to distribute income, but also to offer citizens a genuine equality of opportunities.

So finally, 24 years after the peace accords were signed in Chapultepec, what are the unfulfilled expectations of the people of El Salvador? I believe that the first wish of my fellow Salvadorans is the longing for real peace and true reconciliation after the civil war. Only after achieving it, can we, as a society, aspire to face the many challenges before us and build a better, more cohesive and just country for all.

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Carolina Avalos is an economist and international social policy advisor and former President of the Social Investment Fund in El Salvador. She was a 2015-16 Central American Visiting Scholar at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

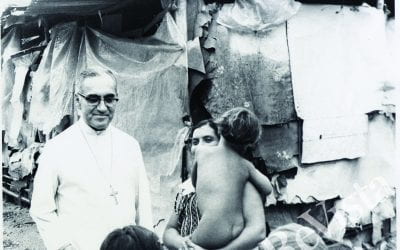

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…