Engraving a City in Flux

An Interview with Max Aruquipa Chambi

Max Aruquipa Chambi’s work focuses on everyday life. Photo by Julio Pantoja/Sudacaphotos.

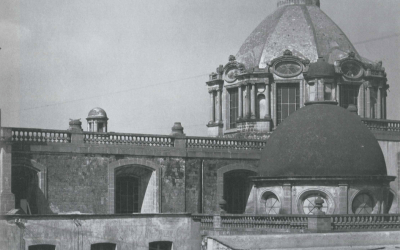

In La Paz, the hills that used to define the city limits overflow with improvised neighborhoods. El Alto, a sprawling satellite city, is poised to become the most populous in the nation. Millions of ex-miners and landless campesinos struggle to make a living in a city that offers precious little opportunities for upward mobility. La Paz is no longer a city of urbanites; it is a migrant center whose identity is slung somewhere between countryside and city.

The experiences of the new paceños, and the city they are helping to transform, inspire an artist who himself was part of the great migrations of the 1960s. In a market that overwhelmingly favors representations of Indians as faceless shadows or folkloric motives, Max Aruquipa Chambi’s work focuses on everyday urban experiences that are nonetheless rooted in a profound intersection of Andean culture and modern urbanism. As part of the group “Benemeritos de la Utopía,” or “Veterans of the Utopia,” Aruquipa is dedicated to inscribing the experiences of a group systematically excluded from Bolivia’s official history.

Aruquipa was born in Santiago de Huata, a village on the shores of Lake Titicaca, a few months before the national revolution of 1952. In his adolescence, he settled in La Paz with his brothers, working in a woodshop during the day and studying at night. He later graduated from the National School of Fine Arts, but was forced to survive as a day laborer during the dictatorships of the 1970s. Since 1983 he has served as a professor in the School of Fine Arts and in the art department of the Universidad Mayor de San Andres, specializing in lithograph and engraving.

This October, while supervising students in the university’s engraving workshop, he settled back on a tool bench to discuss the intersection of art and the urban migrations that are transforming La Paz. The art campus is located in an overgrown garden on the periphery of the city, and, as Aruquipa notes, its isolation and small size tends to foster a family-like familiarity between students and teachers. He speaks in the measured, ponderous Spanish which highland Bolivians, “kollas,” are known for, complementing a temperament which is at once observant, critical, and patiently philosophical. He interrupts himself occasionally to help a student, and to brush back the floppy black hair that persistently falls over his eyebrows.

L: Do you consider yourself part of any particular school or artistic tradition native to La Paz?

MA: Yes, because La Paz has an innate artistic tradition. The men and women of La Paz are naturally artists, in their manner of speaking and even celebrating. I am not saying that we are all painters or drawers, rather that the paceño is a visual artist every day. In dance, for example we have the Señor del Gran Poder (an annual religious parade involving thousands of dancers.) These visual manifestations are in themselves artistic, especially as expressions of the mestizaje that continues to shape the city. These are daily things. The imagistic world of the Aymara and the Quechua is naturally very expressive, very artistic.

Now, the historic tradition of La Paz, where does that come from? I take Arturo Borda as a reference. In literature, we have Franz Tamayo, also a mestizo. These two artists are the pillars of the artistic tradition in La Paz, and why not, in universal art as well.

The idea of a Bolivian nation that comes out of La Paz is very profound. As we are at the apex of all the cultures in Bolivia, our cultural expressions are the most fundamental and enduring. In the tropics, for example, their art does not have so much depth… I think this is the merit of La Paz; it is a land that is able to take in many people, everyone that comes, and there is not ethnic discrimination in that sense. Of course, there are internal prejudices that still exist, against Indians, cholos (urbanized, working-class Indians and mestizos,) etc., but this is also being eliminated through the process of mestizaje.

L: Your conception of mestizaje comes from the Revolution, then, as a process which defines the future of the country?

MA: Of course, this is obvious, I do not believe that there exists a “pure” culture or race … Today all the nouveau riche you see in La Paz, are people with Aymara and Quechua features.

L: Can you tell me more about your group, “Veterans of the Utopia”?

MA: “Veterans of the Utopia” celebrates the five hundred years that have passed since the Spanish conquest. There are five of us, right now we are rather dispersed due to various personal obligations, but soon we want to come together again to dust off this history. We have plunged directly into history precisely because in Bolivia, history has been badly written, whatever fits the interests of the leaders: the politicians, the oligarchy. Those people already have their history written, according to their own interests. But the “Veterans of the Utopia,” as we are all migrants, and we are all rebellious, we see things from a different point of view, and we review history.

One of our projects, for example, was an exposition entitled “500 Años de K´unchiria,” K´unchiria in the Aymara language means “curses.” … We have many themes, we paint issues from the mines, and we paint the passions that exist in every human being. We have many themes to work on as a group, to make art that provokes discussion, and above all does not blindly accept the version of history we have been told…

Right now the United States has the advantage of being able to send its messages rapidly, and people who are misinformed believe everything they hear on television. And this is not right, we have to lead ourselves, we have to maintain the essence and the personality of Bolivian art. We aspire to what is our own. The goals of the Veterans have been precisely this: to rescue, to rediscover our culture, and to resist these bad influences.

L: Why have you focused so much of your art on the city, and on La Paz in particular?

MA: La Paz has its “iman,” its energy. Of course, it is also cursed (“maldita”) at the same time. Take for instance its original name (Chuquiago,) which indicated that this was a sacred place. But as time has passed, so much blood has flown, between Indians and whites, and plenty of people on both sides have died. There is a reason that we also call La Paz “The City of Tyrants”…

All these revolutions that we have been talking about, have grown out of La Paz. The miners in Oruro and Potosi always come here to protest. This is a privilege, in a way, that comes with being the national capital, so that we witness things that they never see in Santa Cruz and other cities. Here, a day does not pass where there is not some sort of march, people coming down from El Alto or one of the provinces, even the soldiers have their strikes! All of this makes La Paz different from any other city.

One of the greatest themes in La Paz is the resistance of the marginal peoples, which we explore in the group “Veterans of the Utopia.”

L: Who makes up the audience for your art in La Paz? How is your art interpreted and accepted in various levels of society?

MA: There are certain sectors of the elite that have taken over the city, especially the means of communication. I attribute to the press, a great deal of misinformation and hypocrisy. So, rarely we have expositions of drawings or engravings, these things are not in such demand from the public: and of course, other techniques are more popular, for example watercolor, which attracts an audience through its pleasing color. Generally, the public is not well-educated in being able to interpret a work of art, they are not prepared. Also, the people from the Zona Sur (the wealthy section of La Paz) and foreigners, like to take their art as colorful souvenirs. People rarely are interested in interpreting engravings… Many even consider engravings as an art form of the elite, obviously that is not the case.

In La Paz, artistic production is still split into two tendencies: art with a social, often revolutionary focus; and art which is decorative and passive. This second type, this inoffensive art, is useful for decorating walls: the best example of this tendency are the colorful neo-Indian designs of Mamani Mamani. This type of art is commercial above all, without a social function, which should not be so. We should not produce art to be like musica chicha (the repetitive cumbias in vogue these days in Bolivia.) I am not achieving much commercial success with my engravings, but I do think my work has something to say about the human being.

L: How can you begin to observe and interpret the experience of the migrant in La Paz?

MA: It is rather painful to speak about this. The phenomenon of urban migration is due to lack of attention from the government, which has so many projects supposedly for the benefit of the campesinos, since the Agrarian Reform Act of 1953. Since the 1960´s there has been a great wave of migration of people from the altiplano, who also have gone to Yungas, Chapare, and Santa Cruz. Some of these migrations have been planned, others no. But what has been happening here in La Paz is that the migrations from the mines and the provinces have filled up El Alto. Of course, these migrations have also brought enrichment, not everything is negative. The cultural aspect is where there are the greatest riches, and in the ethnic and sociological aspects, since there are so many peoples living together here in the city. In this sense, the study of migrations is incredibly fertile.

But of course, there are so many limitations, there is not enough work. Every day you see in the street this sort of improvised work that manages to keep people alive from one day to another. For example there are the women who sell any little thing, and the shoeshiners, lately we have been seeing lots of private security guards; all of these types of work that you did not see in La Paz before, are a result of the migrations.

The artists that focus on these themes, these tragedies, know that this happens every day, that in the altiplano there is no longer land, no more space, and the campesino is forced to migrate. The youth have come to the city, and so in the villages all that are left are the old people and a few toddlers. This means that there is also a loss of values: for example, in the altiplano we used to eat fifty varieties of potatoes, now we are familiar with only five varieties. An Aymara migrant who goes to the tropics completely forgets how to plant a potato or how to play his own music. This is the process of acculturation.

L: Do you try to incorporate Andean symbols in your art, especially as these symbols are translated in the city?

MA: Every place has its symbolic values. La Paz also has its native character. But we should not always identify La Paz with Illimani, llamas and the kantuta (an Andean flower and Bolivia´s national symbol.) Rather, I have seen that working with the students is when one discovers all the possible symbols, the visible and invisible elements possessed by every human being. The wealth of La Paz lies in these young migrants who come together here in the university, here is where I discover the symbolic values that give strength to a culture. Finally, these young artists need a well-nourished culture, so that they may express themselves in their work. Education is the way to construct and reproduce culture.

I am not speaking only of visual art, but also music and dance. I have had the honor to participate in entradas folkloricas in Oruro and the provinces, and I am absolutely convinced that in these expressions lie the cultural essences of each region, and above all of La Paz. So, La Paz should not be renowned simply for Illimani, but above all for the wisdom of its people… In all the world, you cannot find a city like La Paz.

L: What is the greatest challenge for an artist in La Paz?

MA: The challenge would be that the artist may continue to produce in the spirit of the time. That the artist may speak the honest truth. What is important is to leave a testimony, and for this the artist must have a certain level of fame, so that his work spreads all over the world and makes people reflect.

Lindsey McCormack is currently completing research for a Harvard senior thesis on the ideology of Warisata, an educational movement in 1930s Bolivia. She expresses her gratitude to the paceños who have so generously shared their interpretations of Bolivia’s past and future.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

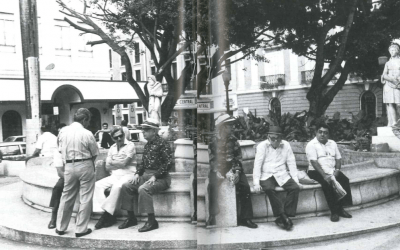

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….