Environment, Indians, and Oil

An Indian leader from the Upper Amazon recently commented to me that the whole issue of the environment, Indians, and oil companies had taken on global mythical proportions. He was partly proud, partly surprised, and partly bemused. For many people, the mythic image evoked by an oilrig hacked into the Amazon Rain Forest, particularly if it looms over Indian communities, is that of Paradise Lost. However, for others who currently view the wide array of communities, institutions, organizations, companies, adventurers, journalists, and other characters, compounded by each’s enigmatic or mutually misunderstood concerns, interests and agendas, the images are more like those molded by Gabriel Garcia Marquez than by John Milton. Beyond comparing narratives, one can also ask if anything can be done to prevent this mix of interests from becoming a social and environmental tragedy in the region. Perhaps. Here we review two recent efforts by Harvard’s Program on Nonviolent Sanctions and Cultural Survival (PONSACS).

An Indian leader from the Upper Amazon recently commented to me that the whole issue of the environment, Indians, and oil companies had taken on global mythical proportions. He was partly proud, partly surprised, and partly bemused. For many people, the mythic image evoked by an oilrig hacked into the Amazon Rain Forest, particularly if it looms over Indian communities, is that of Paradise Lost. However, for others who currently view the wide array of communities, institutions, organizations, companies, adventurers, journalists, and other characters, compounded by each’s enigmatic or mutually misunderstood concerns, interests and agendas, the images are more like those molded by Gabriel Garcia Marquez than by John Milton. Beyond comparing narratives, one can also ask if anything can be done to prevent this mix of interests from becoming a social and environmental tragedy in the region. Perhaps. Here we review two recent efforts by Harvard’s Program on Nonviolent Sanctions and Cultural Survival (PONSACS).

Colombia: Oxy and the U’wa

Ironically, a protagonist in Garcia Marquez’ Noticia de un Secuestro, Colombia’s ex-Minister of Defense Rafael Pardo, helped draw PONSACS into a complex applied research/conflict management project in Colombia. In mid-1996, Pardo, then a Fellow at Harvard’s Center for International Affairs, discussed with me the difficulties of deciphering the complex cultural and political “codes” of those involved in environmental disputes. PONSACS’s interest in disputes involving international extractive companies, Indians, and rain forests were a case in point. Pardo quietly suggested the need for such work in Colombia. About a year and a half later, the Colombian Ministry of Foreign Affairs asked the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States (OAS) to undertake an on-site investigation of a stalemated, multi-stakeholder dispute between an indigenous group –the U’wa– and a multinational oil company, Occidental de Colombia (OXY). Pardo, then working at the OAS, recommended that the Chief of Staff, Ricardo Avila, solicit the participation of Harvard University’s PONSACS Program. The General Secretariat, drawing in its Unit for the Promotion of Democracy, then established the OAS/Harvard Project on Colombia with experts in international law, indigenous rights, and the analysis and prevention of inter-ethnic conflict.

What was going on? In April 1995, U’wa Indians were threatening to commit mass suicide by leaping from a 1,400 foot cliff to protest OXY’s plans for oil exploration in the Samore Block, the Colombian newspaper El Nuevo Siglo had reported. U’wa leaders said that oil production would destroy the world as the U’wa knew it. They and the Colombian national Indian organizationalso argued that all previous oil activities in Colombia’s rain forest had already left a legacy of social and environmental degradation and destruction. In the face of national and international pressure, OXY halted all work in the Samore Block, and sought to open discussions with the U’wa and other critics of the proposed work.

Meanwhile, the Colombian Ministry of Mines and Energy and the national oil company, Ecopetrol were contending that oil-exporting Colombia would become a net importer by the year 2005, thus precipitating a national economic crisis. Other ministries and directorates, particularly the National Ombudsman and the National Directorate for Indigenous Affairs supported U’wa rights. The national Indian organization, while strongly supporting the U’wa, argued that the National Directorate was, in general, an unnecessary paternalistic anachronism.

The U’wa situation prompted the various stakeholders to test aspects Colombia’s progressive 1991 constitution, specifically with regard to indigenous rights. The case thus served as a platform to debate human rights, environmental risks demonstrated by earlier oil exploration, and national economic priorities. It also illustrated the entangled roles of various government ministries, expanded the political space occupied by Colombia’s national Indian organization, increased attention on the environmental and economic impact of international oil companies operating in Colombia. The fact that the Ministry of the Environment’s had approved OXY’s work plan thus became submerged in a flurry of broad national political debates.

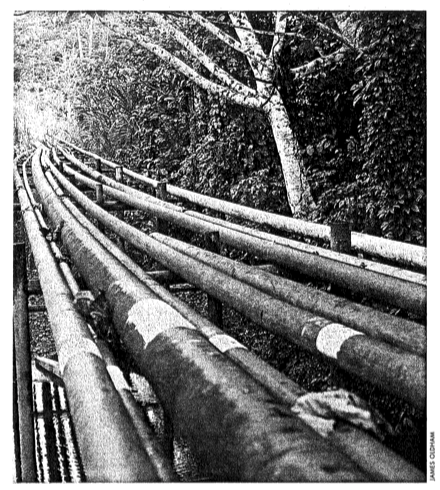

Added to the soup of stakeholders were, and still are, the various factions of the National Liberation Army along with sectors of the well-armed Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces, who regularly blow up OXY’s existing Cano Limon pipeline, and kill oil workers. This in turn has encouraged increased Colombian Army presence. This mix of guerrillas and army, close to the U’wa’s densely forested and mountainous terrain, places the Indians at considerable risk. While most U’wa try to remain neutral, they are simultaneously recruited and questioned by the Colombian army and the guerrillas alike. The clear presence and influence of guerrilla groups also sidetracked many aspects of the national debate with oil companies emphasizing the guerrillas’ influence, while the indigenous organizations insisted that the issue of guerrilla involvement merely blurred Indian rights issues such as consultation and the need to evaluate potential environmental destruction occasioned by oil production.

All dialogues became acrimonious debates. The U’wa’s situation, whether interpreted as a culture and its lands at risk or individual lives in jeopardy, became a platform for arguing group rights and national economic priorities, but the stakeholders weren’t listening to each other. The Ministry of Foreign Relations decided to seek outside help through the newly-formed OAS/Harvard team. At about the same time, the national Indian organizationand the U’wa, with support from US non-governmental organizations submitted a formal complaint to the OAS’s Inter-American Commission on Human Rights..

The OAS/Harvard team’s initial research quickly recognized that, despite the apparent simplicity of this David and Goliath/Garden of Eden case, a complex set of concerns were clearly linked to a wide set of national and international interests. Nonetheless, the team focused its research on what, in its opinion, were the two critical themes: the Colombian Constitution’s stipulated but ambiguous requirements for community consultation and respect for indigenous rights in determining the future of their traditional territories and resources.

The researchers’ recommendations, drawing on much of the pioneering conflict management work at Harvard, focused on issues and concerns apparently shared by the key parties to develop some form of joint problem solving process.

In early September 1997, OAS Chief of Staff Ricardo Avila and the author of this article, PONSACS Associate Director Ted Macdonald, traveled to Colombia to present the team’s report to all of the major stakeholders. The newly elected government of President Andres Pastrana, as well as many of the stakeholders, have now indicated a desire for continued involvement by the OAS/Harvard team, as a means to assure Colombian remains compliance with a “friendly settlement” recommended by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in response to the complaint. As of this writing (September 1998) plans for future work have been made but the second phase of the project is not yet underway.

Though the U’wa/OXY case has obtained one of the highest profiles in the Americas, it is by no means an anomaly. PONSACS has already been asked to undertake similar research and recommendations in two oil-related cases in Ecuador as well as an on-going Indian/forest concession dispute in Nicaragua.

Dialogues on “Oil in Fragile Environments”

Given the extent of mutual misunderstanding and the increased presence of oil activities in the Upper Amazon, PONSACS began a program last year to complement its direct involvement in field activities with broader more traditionally academic efforts through meetings at Harvard. Thus, the program initiated the “Dialogues on Oil in Fragile Environments.” The dialogues were founded on two simple background considerations: (a) exploration for and production of oil in fragile environments, particularly the Upper Amazon regions of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela, have produced a number of reactions and realities that range from non-Governmental organizationsS demands for a total ban on oil production to oil company operations which are insensitive to either social or environmental concerns; (b) presently occupying a large and expanding middle range is a “moderate center,” composed of oil companies, environmental non-governmental organizations and indigenous groups concerned with minimizing the negative impact of resource extraction. There are few, if any forums in which these groups can meet informally and quietly.

The Dialogues were established to provide a framework for analytic, non-adversarial discussions that regularly bring together members of these interested parties in small groups. The meetings are expressly not designed as a forum for negotiation, but for free, open, and confidential exchange. The third-party facilitating team assists the flow of the meetings; the substantive issues, specific format and other aspects of the dialogue are defined, periodically revisited, and agreed upon by the participants themselves. Four oil companies and four non-governmental organizations, which had expressed concern for pursuing the objectives outlined above, participated in the February 1997 dialogue. Since then the group has developed ways to progressively and effectively expand to include more companies and non-governmental organizations, doubling in size since the first meeting.

There has also been a desire for direct participation by those local stakeholder groups involved in or affected by oil exploration and production in fragile environments, including many of the region’s indigenous peoples. Consequently, beginning with the September 1998 meetings at Harvard, indigenous representatives experienced in oil issues, from Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, will participate in the Dialogues. The long-term goal is to establish a permanent, yet informal forum for discussion and clarification of inevitable misunderstandings and disputes.

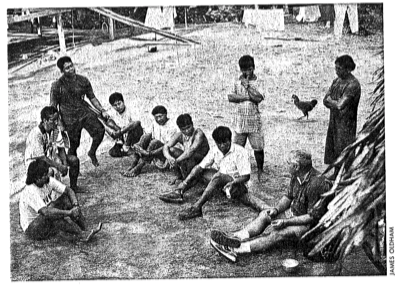

Ted Macdonald, far right, discusses oil negotiation

These illustrative projects are, in a sense a form of “preventative diplomacy.” Given the current and often conflictive need to reconcile evolving international human rights norms with the perceived government need to attract foreign investment in Latin America, conflicts will inevitably increase. However, disagreement and conflict, provided that they are not met with repression and violence, are signs of a healthy and normally “messy” democracy. The expanding and direct role of indigenous peoples in environmental disputes with some perceptions of national development need not be a threat to stability. On the contrary, such participation illustrates expanded, and thus positive, political pluralism within culturally plural and traditionally asymmetric societies.

For more information on PONSACS consult its Website – http://data.fas.harvard.edu/cfia/pnscs

Fall 1998

Theodore Macdonald, anthropologist, is Associate Director of the Program on Nonviolent Sanctions and Cultural Survival at Harvard’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. His most recent book, Ethnicity, and Culture Amidst New Neighbors: The Runa of Ecuador’s Amazon Region chronicles some of his research in the area, beginning in the early 1970s.

Related Articles

The Urban Environment

Urbanization has transformed Latin America over the last forty years. Its cities, always diverse and lively, have now also become chaotic and centers of social conflict. Millions of subsistence…

The Environmental Agenda in Latin America

f the eighties was the decade of economic reforms, and the nineties that of political and social reforms, the 21st century will be that of environmental concerns. Environmental integrity…

The Environment

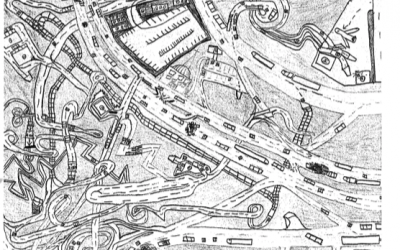

In planning my schedule for the weeks of research I spent on the U.S.-Mexican border this summer, I knew I would have to factor traffic into my plans. This was certainly on my mind as…