Ephemeral Memorials

The emotional challenges of Covid-19 have been immense, especially when it comes to memorializing the dead—both our own loved ones and the nameless others lost in an enormous pandemic. People worldwide could not practice customary funerary and remembrance rites—activities which help manage trauma and grief. Large, traumatic events—war, natural disasters, genocide, and disease—spur the creation of memorials, and we think of memorials as being made of marble (which seems so wonderfully permanent, but is not, given acid rain).

However, I am going to argue the opposite: that sometimes the ephemeral and personal memorial may be the most effective for honoring and remembering losses. Cultures rooted in Latin America have demonstrated a powerful, flexible, yet fleeting way of memorializing both family and unknown victims of the pandemic using ofrendas and the celebrations of Todos Santos, or Días de los Muertos. The ofrenda and associated traditions originating in Latin America have some advantages in helping individuals manage profound grief and loss in the pandemic due to their inherent mutability—perhaps the opposite of a stone monument.

The ofrenda —the household altar dedicated to deceased family members—features transitory elements—bread, sweets, fruits, cooked dishes, candles, both alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages and flowers, particularly marigolds, known as “flowers of the dead.” All these items associate the altar with the natural processes of death and decay. Foods are meant to be eaten or they rot, cut flowers begin to deteriorate the moment they are separated from the plant, and candles burn down to nothingness. For those familiar with art history, ofrendas are three-dimensional versions of the Northern Baroque still lives which served as memento mori (reminders of death) for wealthy, pious homes by showing transitory items. However, the lush, multicolored tulips in those paintings retain their preserved elegance centuries after the tiny brush touched the canvas, while the marigolds on the ofrenda are allowed to decay and be replaced.

\

\

Photographs of the departed are very common on the altars. Since its inception, photography has been associated with death because of its ability to arrest time, just as death stops life. Because analog photographs record moments that cannot be repeated, philosopher Roland Barthes has called cameras “clocks for seeing” and speaks of a concept of “that-has-been” which exists in every photograph. The invention of photography benefited the ofrenda tradition immensely, as by the mid-19th century, photographs were relatively inexpensive and allowed for ongoing customization of each altar rather than a static and unchanging monument. As time and family members passed, photographs could be added to the display

As an aside, I have a friend who rented a Midwestern apartment above a funeral home for many years. Probably because my friend is a photographer, his landlord, the funeral director, told my friend about some recent Spanish-speaking clients and the importance of photographs. The clients requested some time alone in the funeral parlor, and, of course, the funeral director stepped aside to let them have private time. The director returned to find the body somewhat rearranged in the casket. The family had been taking pictures with the deceased. I have always imagined those photographs as gracing an altar in that Midwest town.

During Todos Santos (November 1-2) both the offerings and their display location change, as mourners add pan de muerto (bread symbolically representing a skeleton), papel picado (cut tissue paper banners) and handsomely decorated sugar skulls. Around the holidays, sales of pan de muerto, sugar skulls, and marigolds soar, people hold parades in death-themed costume, and families visit and decorate graves using methods of the home ofrenda as a signal to attract the departed for a chat during that brief chance to reconnect. For this reason, the word choice of “cemetery” over “graveyard” or “burial ground” would always be the best in a Latin American cultural context, for the word “cemetery” comes from the Greek meaning “to put to sleep.” Those buried are not gone, but simply resting.

With Covid-19 raging, November 1-2, 2020, had to be different, and it was. However, unlike marble memorials to the dead, the traditions of the ofrenda and Días de los Muertos had the elasticity to immediately accommodate at least some of the needs to mourn and remember –even to honor disease victims the mourners had not known in life.

Some traditions of Días de los Muertos were not possible, particularly visiting the cemeteries where usually an ofrenda would normally be created. For example, the Mexican government closed access to cemeteries where families might gather and place symbolic objects. For the most part, cemeteries were open only to a limited number of mourners for burials, but not for holiday, ritual events.

However, adaptations to changed circumstances were immediate. The mayor of Mexico City declared three days of official pandemic mourning beginning October 31, 2020, and erected an ofrenda at the National Palace dedicated to Covid-19 lives lost (at that time approximately 90,000 in Mexico). For the record, on November 1, 2020, the seven-day moving average of new cases in Mexico was 5,462—a number that soared to 17,463 in the following months. As of this writing, 263,470 Mexican citizens have died of Covid-19.

In the absence of large gatherings, some celebrations during 2020 moved online to continue communal mourning. For example, the Hispanic Business Alliance (HBA) of New Braunfels, Texas, hosted a virtual party and showed Disney’s Coco at a drive-in movie theater. HBA Chair Shelley Bujnoch reflected on the way that the occasion could reach those affected by Covid everywhere, remarking, “There’s no color; there’s no denomination; there’s no political view when it comes to losing somebody, and everybody has been touched by the loss of a loved one. And so I think that’s what makes it so important to be able to continue that tradition.” In San José, California, large events were cancelled; however, altars were shared online, many of which included references to the pandemic. Artist Phyllis Carrasco, who organized some of the local events, included a photo of one of people first to die of Covid-19 in the area, Arcelia Martínez, who was not part of Carrasco’s biological family.

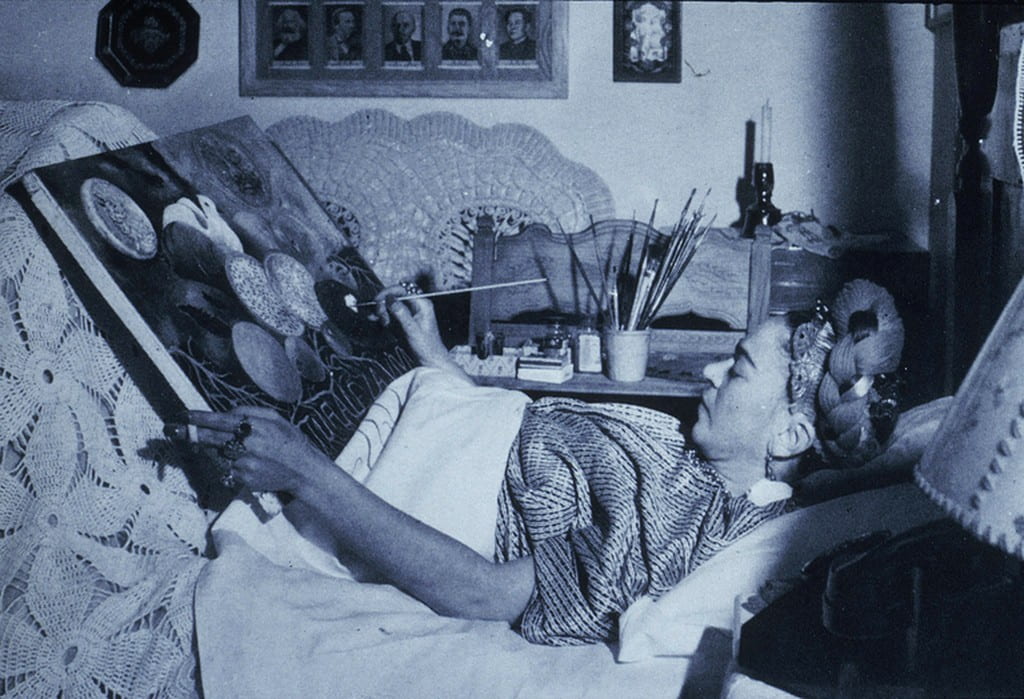

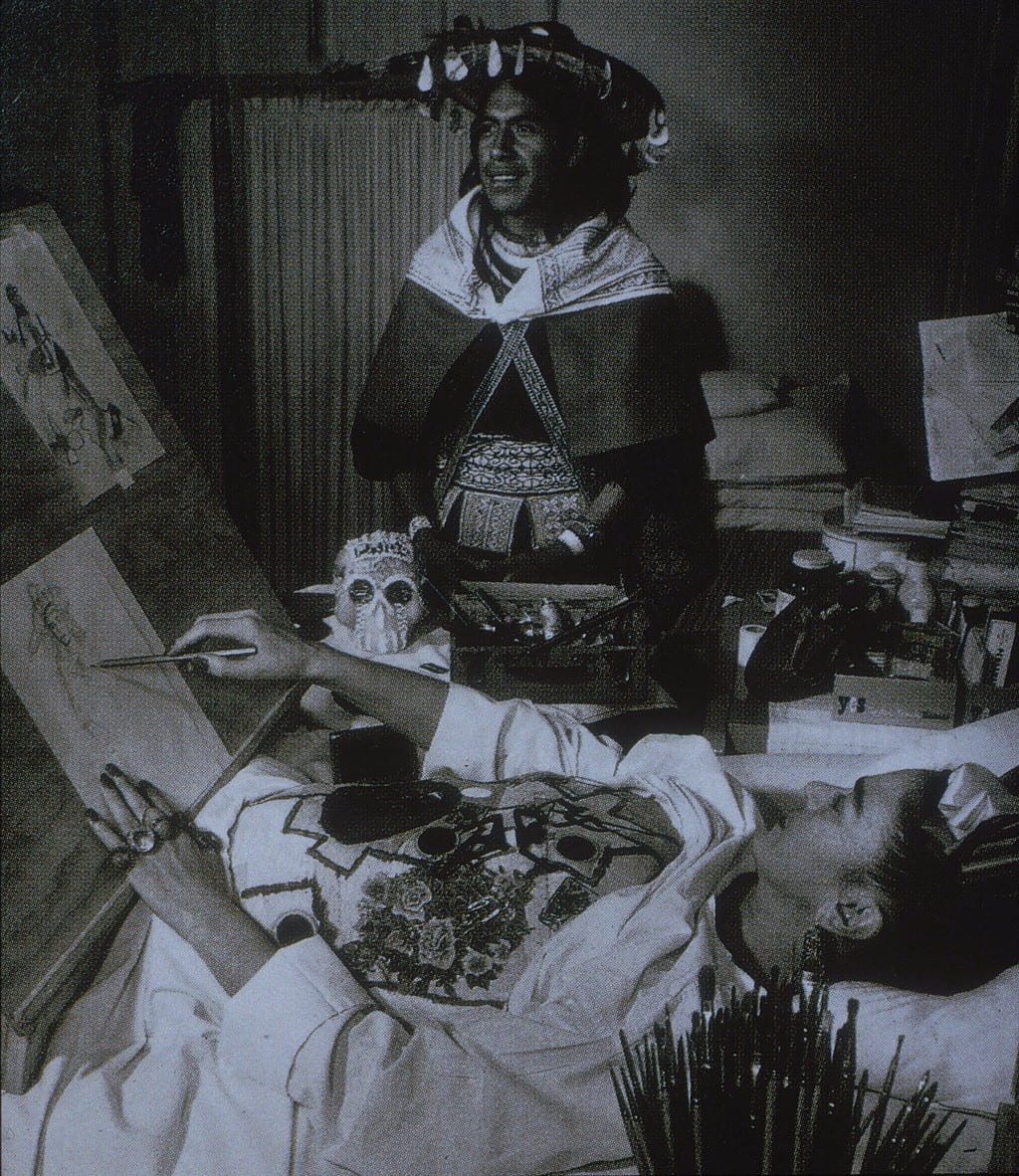

Instead of parades in full costume, some wore protective masks made out of fabric imprinted with skulls or skeletal parts. Directors at the Museo Frida Kahlo (in La Casa Azul in Mexico City) teamed up with fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier to create an altar entitled “The Restored Table: Memory and Reunion,” a tribute to artists who died in a pandemic. A few choices are questionable for the “pandemic” category, but plague is represented by Titian and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, tuberculosis by Chopin, Spanish flu by Gustav Klimt, and AIDS by Keith Haring, among others. The location of this exhibit, in the home that Kahlo and Rivera inhabited and re-invented on a continual basis, is important. During her lifetime, Kahlo’s slept in her own ofrenda. Very often confined to bed because of a terrible injury, she installed a mirror on the canopy above (in order to paint self-portraits) as well as a papier-mâché skeleton. At the head of the bed photographs of herself, loved ones, and admired (and dead) political figures (Lenin, Marx) stood watch.

As a gender-bender and supporter of Marxism, Kahlo was no stranger to countering accepted beliefs. Since so many of Días de los Muertos rituals either went online or were displayed in public (as in Covid masks), one might read the observation of November 1-2, 2020 as a kind of counter-protest regarding health care among different populations. News reports have revealed worldwide disparities in health care, particularly during a pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control’s sobering report, “Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity” says that compared to “White, non-Hispanic Persons,” “Hispanic or Latino Persons” demonstrated 1.9 times the number of cases, 2.8 times the number of hospitalizations, and 2.3 times the number of deaths. In fact, only “American Indian or Alaska Native, Non-Hispanic Persons” exceeded that death rate at 2.4 times the number of “White, non-Hispanic Persons.” I think to myself, “Houston, we are going to need a lot more help for November 1-2!” However, with the online, drive-in and drive-by presences, an opportunity became available to make death visible to others new to those traditions.

During 2020, families welcomed both Covid victims known by name as well as those without a name to their homes and to their traditions in a way that any eventual memorials made of permanent materials cannot do. In my mind’s eye, I see Kahlo’s toothy calavera smiling.

Spring/Summer 2021, Volume XX, Number 3

Emily Godbey has a Ph.D. in Art History from the U. of Chicago and an MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. As an associate professor at Iowa State University, she works on topics in photography and early film—mostly ones involved with death and destruction.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...