Exhausted Women

We women are tired. Physically and psychologically. It is not just the fatigue due to the pandemic, or that of a particular context. It is historical fatigue, transmitted and accumulated, from generation to generation, from the origins. “The mother has not been able to transmit to the daughter but the capitulation, the idea of the limit that should not be crossed, threatened with exclusion and with the risk of not being considered a woman or feminine,” said Mexican writer Silvia Marcos—quoting the Italian psychologist Franca Ongaro—in 1978 at an alternative psychiatry congress. How won’t we women not be tired?

Like the universe, which is expanding at an ever-increasing speed, the fatigue of women is growing rapidly and worryingly in our times. It is as if, in the collective subconscious of the females underlies the “I have to” as an implacable self-supervisor who does not allow them to take a break, or forgive a mistake, in a continuous effort to feel worthy of their achievements, attention, and affection. The Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han points out that the pressure to produce of the last generations had the sad result of increasing consumerism and not necessarily, at the same level, well-being. This generated a tired society where human beings are their own supervisors who punish themselves by permanently raising their own levels of demand.

Historical efforts and the accumulated fatigue of so many years of struggles are added up to us women: for having the right to life, freedom of decision, the right to education, to be able to vote, have a bank account, get married or not — when, how and with whom they want — to have a place at the decision table and a voice that is heard and respected. Let us not fool ourselves. When their advances passed on to us, our predecessors also passed on their sufferings. We accumulate achievements, we accumulate fatigue.

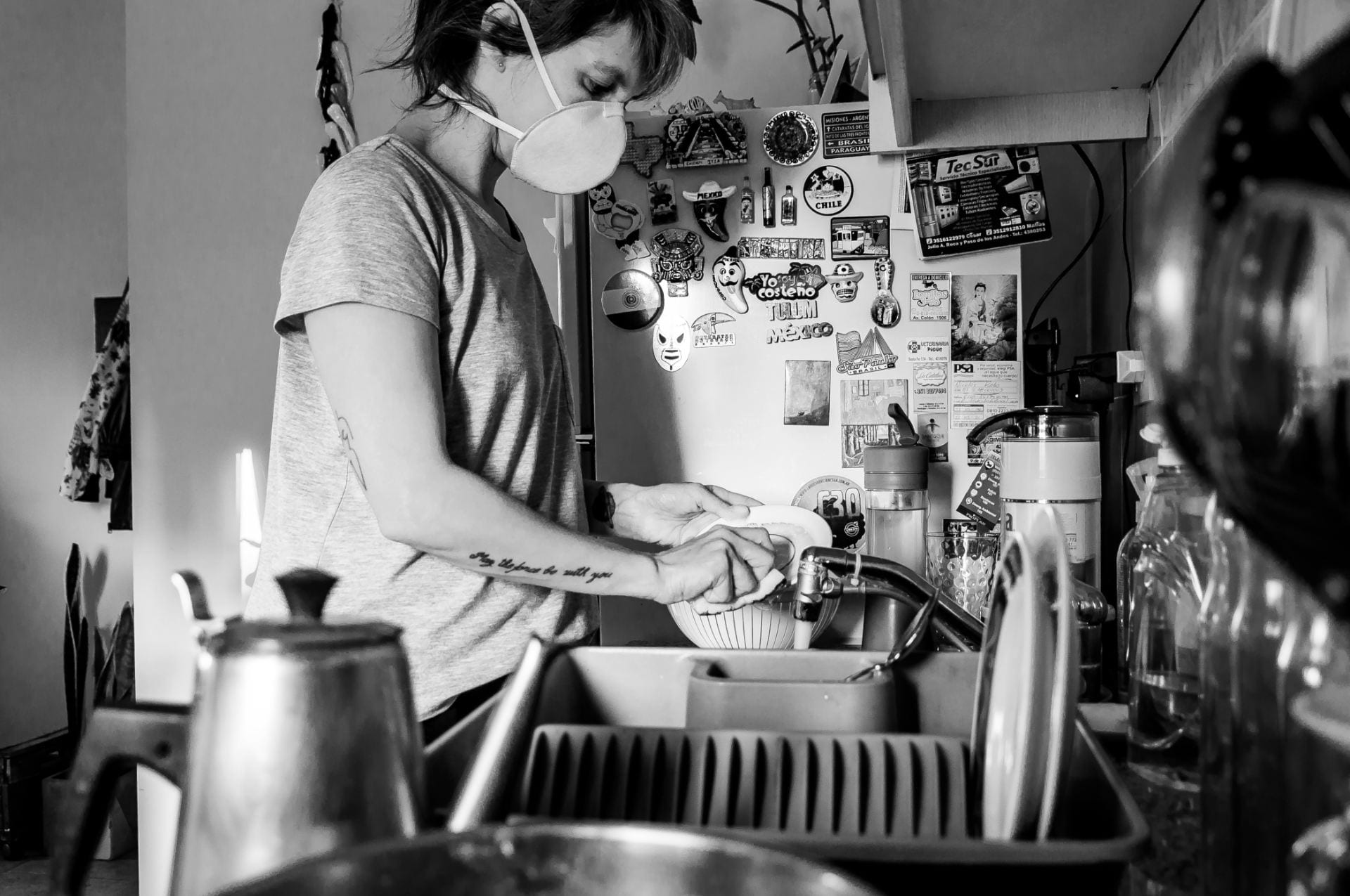

Venezuelan woman: “We Can’t Stop” Love. Photo by Andrea Hernández Briceño, who was chosen to participate in the DRCLAS digital exhibition, “Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 Through Photography,” curated in collaboration with ReVista and the Arts, Culture and Film Program.

Much is being written these days about women, about how the pandemic has affected them the most. It is women who, in this crisis, have lost the most jobs, have increased their family responsibilities, have worked in the most affected sectors—such as health— and have suffered the most serious consequences of domestic violence.

The numbers are, to say the least, worrying. During the first months of the pandemic, for example, in El Salvador, the police registered a 30% increase in calls related to violence against women. In Colombia, there was up to a 118% increase, and in the province of Buenos Aires in Argentina, up to a 60% increase in emergency calls for the same reasons, according to the United Nations Human Rights Office.

Several international organizations — such as the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), or the United Nations — consider that, in Latin America, we are losing in this crisis the progress made in recent decades on issues of gender equality. For this reason, the crisis recovery projects designed by the governments of the region should give priority to women and girls, according to María-Noel Vaeza, United Nations Regional Director for Women for the Americas and the Caribbean.

In most developing countries, women occupy a large part of informal jobs and are therefore in more vulnerable situations than men. In Latin America, this situation is even more marked since there is a large concentration of women in sectors with very low wages and without social protection, reaching up to 83% in Bolivia, Guatemala, and Peru.

Fewer resources mean more work. More work leads to a shortage of time and the lack of the slightest space to breathe, rest, take care of yourself, in short, exist. In the Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present (Herder Editorial, 2020), Byung-Chul Han considers that “time lacks… a firm framework… It disintegrates in the mere succession of a punctual present. It rushes without interruption. Nothing offers him a foothold. Time that rushes in without interruption is not livable. “”

Thus, we come to have an increasingly “less livable” life, with little time to rest, think, feel happy or sad. Sadness or melancholy are necessary and create a psychological balance because they help us to understand our own behaviors and adjust our reactions to the events that occur in our lives. In recent years, the obsessive pursuit of happiness has made these feelings “unpopular,” forcing us to pretend. Pretending to feel different from reality is another factor that contributes to psychological fatigue.

As women acquired more rights, our sense of guilt also grew. To all of us, as Silvia Marcos’sMarcos’s quote said, we have been told that the priority is families, the survival of children, or the care of the elderly. Spending time educating yourself, taking care of yourself, having a professional career, cultivating your spirit should be done in addition to the above. In fact, more than winning, women have added more responsibility by losing spaces with ourselves, so necessary for the body and spirit to rest. Like now, in theory, we can “have it all”, and we feel guilty if we do not try to achieve everything. We perceive the opportunity as an obligation. We have not arranged better. Rather we have loaded more. So, to fatigue, we add guilt.

The year of the pandemic has also accentuated another ancestral feeling, fear. The inner conflict in which human beings live in times like today rises to higher levels in women’s case. On the one hand, being mindful knows that you must show courage and project confidence in difficult times, be it for your children, the elderly, employees, or your patients. As the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung said, fear is ancient and underlies our unconscious. It is necessary to defend ourselves from dangers. However, a permanent inner fear produces a tension that is even more tiring. And so, tiredness, guilt, and fear are reinforced.

“Cellist from Sky” in Panama. Photo by Luis Acosta Castro, who was chosen to participate in the DRCLAS digital exhibition, “Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 Through Photography.”

What can be done? An appropriate cry of despair to be able to start again.

The Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran said in The Heights of Despair (Tusquets, 2012) that o” human beings have not yet understood that the age of superficial enthusiasm is over and that a cry of despair is much more revealing than a more subtle call, that a tear has a deeper origin than a smile. “”

Perhaps we do not have to come to the cry, but we do have to reflect before continuing to perpetuate fatigue, guilt, and fear, and to concrete measures that introduce lasting changes in the lives of women, such as those mentioned in this article.

Let us see some proposals for improvement that would have a positive impact on the quality of life of women in our region, collected from multiple sources, readings, conferences, articles, programs, and conversations with women, experts, leaders of academic institutions, or private organizations or public, during the last years:

Access to universal health.

Universal health is an issue in which Latin America, again, is lagging. Compared to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), where spending on public health is above 8% GDP, in Latin America and the Caribbean, it does not reach 4%.

Health problems further increase inequality and poverty as they prevent people from developing mentally and physically to their total capacity, increasing their productive activities and income level. Likewise, access to health is not only due to the lack of available services but to the reduced mobility that women in our region must reach the places where they can receive care. This brings us to the next problem.

Mobility

Mobility and poor road infrastructure throughout Latin America pose a barrier to progress for the entire population, men and women. For women, it represents an even greater barrier, both because it prevents them from accessing health services, as well as the movement to regions with access to education or better jobs. It is about ensuring not only better means of transportation but also their safety so that women can travel without fear of their physical integrity, citing a study by ECLAC. With greater mobility, women can start looking for new opportunities. However, there is still another issue to be resolved for this to happen: care networks.

“Collective Isolation in the Sibundoy Valley 06” in Colombia. Photo by Nicolo Filippo Rosso, who received an honorary mention in the DRCLAS digital exhibition, “Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 Through Photography.”

Care networks

As I mentioned at the beginning of the article, women are expected to take care of their families, both older and younger, in addition to taking care of their education and economic progress. Equality laws, imported from developed countries, do not have the same applicability in Latin America since support systems for the care of dependent people are non-existent or very deficient. Programs such as Red Cuidar+ —an alliance between the European Union, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the French Development Agency (AFD)— seek to unify initiatives in the region to share best practices and gather resources to improve national systems. With better health, greater capacity to mobilize, and more support for the care of people in their positions, we still have the challenge to approach to open access for more opportunities for women of all social levels in the region: access to the Internet.

Internet access

According to Henrietta Fore, UNICEF Executive Director, “The fact that so many children and young people do not have the Internet in their homes is more than a digital divide: it is a digital precipice.” In a 2020 report by UNICEF and International Telecommunication Union (ITU) about children and their internet access in their homes, it is noted that, in Latin America, more than 74 million, that is, 49%, do not have this service. Again, within this group, these are the girls who have even less access given that they are assigned more household chores or have limited use by their families for cultural reasons. Without internet access, without mobility, access to education, which is the main engine of personal progress, is automatically limited.

Education

The Giga initiative, led by UNICEF and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), which includes more than 800,000 schools in 30 countries, within the framework of the “Reimagining education project, seeks to improve the education of children by increasing and facilitating their internet access. Without education, with little mobility, all children have little hope for a better future in underdeveloped countries. Particularly, girls are condemned to repeat the fate of their mothers and grandmothers, limiting themselves to precarious, informal jobs, without any type of social protection.

Young women who belong to households with higher income also have to face challenges in terms of their education, since, culturally, they are oriented more towards careers associated with women – such as health services, human resources, communication – with lower salaries and projection future (Ilie, C., Cardoza, G., Fernández, A., & Tejada, H. (2018). Entrepreneurship and Gender in Latin America. Available at SSRN 3126888). Developing careers in areas where there are higher projections of quality jobs and better salaries — such as science, engineering, finance — would ensure a more equal starting point for young women in our region.

Like girls, women of high social levels have their challenges in terms of promotion opportunities, equal salary levels, being able to combine all the demands in the personal and professional fields. This group, in particular, tends to push themselves to meet self-imposed standards to be an example, always to be well, and not to complain. Similarly, psychological fatigue, guilt, and fear are present, differently but no less intensely, among these groups of women.

“The Seven Sundays of the Week #1” in Córdoba, Argentina. Photo by Marisa Arce Zencich, who was chosen to participate in the DRCLAS digital exhibition, “Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 Through Photography.”

Meanwhile, to move forward without waiting for the laws to change or for organizations to change their structures and cultures totally, there are simple things that we can develop that often make a big difference. To establish spaces to stop and reconnect with the essence of being, awaken a more universal consciousness, talk and listen without haste, without judging, ask for help, count on other women, strengthen the bonds of friendship and solidarity, create great small moments, can make a big difference. As the Chilean writer Gabriela Mistral said, “Remembering a good moment is feeling happy again.”

Women also need to look within again – in silence – to listen to what our heart and intuition tell us, to create a life that makes sense for ourselves. As Jung said in his last interview, “… we need more understanding of human nature, because the only real danger that exists is the human being himself.”

At a generational level, adults can stop the chain of transmission of the “I have to” to girls. Sir Ken Robinson used to say that “schools kill the innate creativity” of children. The school of life, where we transmit to girls who they have to be, kills their ability to live freely, without predetermined expectations, without recipes for success. If we add to them the great inequalities that, unfortunately, girls experience in developing countries, such as Latin America, we transmit to them an unbearable weight of being a woman.

If we continue to teach girls that a woman’s first vocation will always be to please, we will dramatically restrict her world of personal fulfillment. In this way, individuation, an essential process that brings together the individual and collective unconscious to help develop the personality of a human being, is marked by the ancestral feelings — fear, guilt, fatigue — that we are transmitting to them.

There is still hope. To do this, as the French writer Simone de Beauvoir said, we must accept the great adventure of being ourselves and not feel guilty or fear to recognize that we are tired and that we need help.

Mujeres Cansadas

Por Camelia Ilie

Las mujeres estamos cansadas. Física y psicológicamente. No es solo el cansancio por la pandemia, o el de un contexto particular, es un cansancio histórico, transmitido y acumulado, de generación en generación. “La madre no ha podido transmitir a la hija sino la capitulación, la idea del límite que no se debe trasponer, amenazada de exclusión y con el riesgo de no ser considerada mujer o femenina”, escribió la escritora mexicana Silvia Marcos— citando a la psicóloga italiana Franca Ongaro—en 1978 en un congreso de psiquiatría alternativa. ¿Cómo no vamos a estar cansadas las mujeres?

Igual que el universo, que se expande a una velocidad cada vez mayor, el cansancio de las mujeres está creciendo de forma acelerada y preocupante en nuestros tiempos. Es como si en el subconsciente colectivo de las féminas subyace el “tengo que” como un supervisor implacable que no les permite darse un respiro, ni perdonarse un error, en un continuo esfuerzo para sentirse merecedoras de sus logros, la atención y el afecto.

El filósofo coreano Byung-Chul Han señala que la presión por producir de las últimas generaciones tuvo el triste resultado de aumentar el consumismo y no necesariamente, en el mismo nivel, el bienestar. Esto generó una sociedad cansada en donde los seres humanos son sus propios supervisores que se autocastigan elevando permanentemente sus niveles propios de exigencia.

Venezuelan woman: “We Can’t Stop” Love. Photo by Andrea Hernández Briceño, who was chosen to participate in the DRCLAS digital exhibition, “Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 Through Photography,” curated in collaboration with ReVista and the Arts, Culture and Film Program.

En las mujeres se suman los esfuerzos históricos y el cansancio acumulado de tantos y tantos años de luchas: por tener el derecho a la vida, la libertad de decisión, el derecho a la educación, poder votar, tener una cuenta bancaria, casarse o no—cuándo, cómo y con quien quieran—tener un lugar en la mesa de decisiones y una voz que se escuche y sea respetada. No nos engañemos. Cuando nos legaron sus avances, nuestras antecesoras nos pasaron también sus sufrimientos. Acumulamos logros, acumulamos cansancio.

Mucho se está escribiendo estos días sobre las mujeres y sobre cómo la pandemia las ha afectado más. Son las mujeres quienes durante esta crisis han perdido más empleo, han aumentado sus cargas familiares y han sufrido las consecuencias del incremento de la violencia doméstica.

Las cifras son muy preocupantes. Durante los primeros meses de la pandemia, según la Oficina de Derechos Humanos de las Naciones Unidas en El Salvador la policía registro un 30% de incremento en el número de las llamadas telefónicas relacionadas con la violencia contra las mujeres. De acuerdo con el mismo reporte, Colombia se registró hasta un 118% de incremento y en la provincia de Buenos Aires en Argentina hasta un 60% de incremento de las denuncias por las mismas razones.

Varios organismos internacionales—como la Comisión Económica para América Latina y El Caribe (CEPAL), el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID) o las Naciones Unidas—consideran que en América Latina estamos perdiendo en esta crisis los avances logrados en las últimas décadas en temas de igualdad de género. Por ello, los proyectos de recuperación de la crisis diseñados por los gobiernos de la región deberían dar prioridad a las mujeres y las niñas, según María-Noel Vaeza, Directora Regional de Naciones Unidas Mujer para las Américas y el Caribe.

En la mayoría de los países en desarrollo, las mujeres ocupan una gran parte de los trabajos informales y, por ello, están en situaciones más vulnerables que los hombres. En América Latina está situación es aún más marcada ya que hay una gran concentración de mujeres en los sectores con salarios muy bajos y sin protección social, alcanzando hasta un 83% en Bolivia, Guatemala y Perú.

Menos recursos implica más trabajo. Más trabajo conlleva escasez de tiempo y conduce a la falta del más mínimo espacio para respirar, descansar, cuidarse, en definitiva, ser. En La desaparición de los rituales: una topología del presente (Herder Editorial, 2020), Byung-Chul Han considera que “al tiempo le falta…un armazón firme…se desintegra en la mera sucesión de un presente puntual. Se precipita sin interrupción. Nada le ofrece asidero. El tiempo que se precipita sin interrupción no es habitable.”

Cada vez más la vida es “menos habitable”, con poco tiempo para descansar, reflexionar, sentirnos felices o tristes. La tristeza y la melancolía son necesarias para crear un balance psicológico y entender nuestros propios comportamientos y ajustar nuestras reacciones a los eventos que ocurren en nuestras vidas. La obsesiva búsqueda de la felicidad de los últimos años ha hecho “impopulares” estos sentimientos, forzándonos a pretender. Fingir sentirse de una forma diferente a la real es otro de los factores que contribuyen al cansancio psicológico.

En la medida que las mujeres adquirimos más derechos, también crece nuestro sentido de culpabilidad. A todas, como decía la cita de Silvia Marcos, se nos ha transmitido que la prioridad son las familias, la sobrevivencia de los hijos, o el cuidado de los mayores. Dedicar tiempo para educarse, cuidarse, tener una carrera profesional, cultivar su espíritu debe hacerse además de lo anterior. En realidad, más que ganar, las mujeres hemos sumado más responsabilidad perdiendo espacios con nosotras mismas, tan necesarios para que el cuerpo y el espíritu descansen. Como ahora, en teoría, podemos aspirar a “tenerlo todo”, nos sentimos culpables si no intentamos alcanzar todo. La oportunidad la percibimos como obligación. No hemos compaginado mejor, mas bien nos hemos recargado más. Así que, al cansancio, sumamos la culpabilidad.

El año de la pandemia ha hecho aflorar además otro sentimiento ancestral, el miedo. El conflicto interior en el que viven los seres humanos en tiempos como los actuales se eleva a niveles superiores en el caso de las mujeres. Por un lado, el ser consciente sabe que tiene que mostrar valentía y proyectar confianza en tiempos difíciles, ya sea para sus hijos, los mayores, los empleados, o sus pacientes. Como decía el psicólogo suizo Carl Jung, el miedo es ancestral y subyace en nuestro inconsciente. Es necesario para defendernos de peligros. Sin embargo, un miedo interior permanente produce una tensión que cansa aún más. Y así, se refuerzan el cansancio, la culpabilidad y el miedo.

“Cellist from Sky” in Panama. Photo by Luis Acosta Castro, who was chosen to participate in the DRCLAS digital exhibition, “Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 Through Photography.”

¿Qué se puede hacer? Un oportuno grito de desesperación para poder empezar de nuevo

Decía el filósofo rumano Emil Cioran en Las cimas de la desesperación (Tusquets, 2012) que “los seres humanos no han comprendido todavía que la época de los entusiasmos superficiales está superada y que un grito de desesperación es mucho más revelador que una llamada sutil y una lágrima tiene un origen más profundo que una sonrisa.”

Quizás no tenemos que llegar al grito, pero sí, a la reflexión antes de continuar perpetuando el cansancio, la culpabilidad y el miedo. Urgen medidas concretas que introduzcan cambios perdurables en la vida de las mujeres.

Revisemos algunas propuestas de mejora que tendrían un impacto positivo en la calidad de vida de las mujeres, recogidas de múltiples fuentes, lecturas, conferencias, artículos, programas y conversaciones con mujeres, expertos, líderes de instituciones académicas, o de organizaciones privadas o públicas, durante los últimos años:

Acceso a la salud universal

La salud universal es un tema en el que América Latina, de nuevo, continúa rezagada. De acuerdo con la Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos (OCDE), en cuyos países el gasto en salud pública está por encima del 8% del PIB, en América Latina y el Caribe no llega al 4%.

Los problemas de salud aumentan aún más la desigualdad y la pobreza ya que se combina con otros factores para impedir que las personas se puedan desarrollar mental y físicamente en su plena capacidad, que puedan aumentar sus actividades productivas y su nivel de ingresos. Igual, el acceso a la salud, no se debe solamente a la falta de servicios disponibles, sino a la reducida movilidad que las mujeres en nuestra región tienen para llegar a los sitios en donde puede recibir atención. Esto nos lleva al siguiente problema.

Movilidad

La movilidad y la carencia de las infraestructuras viales en toda América Latina implican una barrera al progreso para toda la población, hombres y mujeres. Estas deficiencias representan una barrera mayor pues impiden el acceso a servicios de salud y el desplazamiento hacia regiones con acceso a la educación o a mejores empleos. Según la CEPAL, en el caso de las mujeres se trata de asegurar, no solamente mejores medios de transportes, sino la seguridad para que puedan viajar sin miedo a su integridad física. Con mayor movilidad, las mujeres pueden empezar a buscar nuevas oportunidades. Sin embargo, todavía queda otro tema por resolver para que esto ocurra: las redes de cuido.

“Collective Isolation in the Sibundoy Valley 06” in Colombia. Photo by Nicolo Filippo Rosso, who received an honorary mention in the DRCLAS digital exhibition, “Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 Through Photography.”

Redes de cuido

Como mencionaba al inicio del artículo, se espera que las mujeres se hagan cargo de sus familias, tanto de los mayores como de los menores, además de ocuparse de su cuido, educación y desarrollo integral. Las leyes de igualdad, importadas de los países desarrollados, no tienen la misma aplicabilidad en América Latina ya que los sistemas de apoyo para el cuidado de las personas dependientes son inexistentes o muy deficientes. Iniciativas como la Red Cuidar+—una alianza entre la Unión Europea, el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID), y la Agencia Francesa de Desarrollo (AFD)—buscan unificar las iniciativas en la región para compartir mejores prácticas y reunir recursos para mejorar los sistemas nacionales. Con mejor salud, mayor capacidad para movilizarse y más apoyo para el cuido de las personas a sus cargos, nos queda todavía un reto que abordar para abrir el acceso a más oportunidades para las mujeres de todos los niveles sociales en la región: el acceso a internet.

Acceso a Internet

Según Henrietta Fore, Directora Ejecutiva de UNICEF, “El hecho de que tantos niños y jóvenes no tengan Internet en sus hogares es más que una brecha digital: es un precipicio digital.” En el informe publicado en 2020 por la UNICEF y la Unión Internacional de Comunicaciones (UIT) sobre los niños y su acceso a internet en sus hogares, se señala que, en América Latina, más de 74 millones, es decir un 49%, no tienen acceso a este servicio. Dentro de este grupo, de nuevo, son las niñas quienes tienen aún menos acceso dado que tienen asignadas más tareas domésticas o tienen limitado el uso por sus familias, por razones culturales. Sin acceso a internet y sin movilidad se limita automáticamente el acceso a la educación, principal motor de progreso personal.

Educación

La iniciativa Giga, liderada por la UNICEF y la Unión Internacional de Comunicaciones (UIT), que incluye a más de 800.000 escuelas en 30 países, en el marco del proyecto “Reimaginar la educación”, busca mejorar la educación de los niños incrementando y facilitando su acceso a internet. Los niños tienen poca esperanza para un futuro mejor en los países subdesarrollados sin acceso a la educación. En particular, las niñas están condenadas a repetir el destino de sus madres y abuelas, limitándose a trabajos precarios, informales, sin ningún tipo de protección social. Vidas precarias donde también se restringe el derecho a soñar y cambiar.

Las jóvenes que pertenecen a hogares con mayores ingresos también tienen que enfrentar retos en cuanto a su educación, ya que culturalmente se les orienta más hacía ´carreras femeninas´ –servicios de salud, recursos humanos, comunicación, entre otras – con menos salarios y proyección a futuro (Ilie, C., Cardoza, G., Fernández, A., & Tejada, H. (2018). Entrepreneurship and Gender in Latin America. Available at SSRN 3126888). Desarrollar carreras en áreas en donde hay mayores proyecciones de empleos de calidad y con mejores salarios—ciencias, ingenierías, gestión—aseguraría un punto de partida más igualitario para las jóvenes de nuestra región.

Las mujeres de niveles sociales altos también afrontan sus retos en cuanto a oportunidades de promoción y niveles salariales desiguales. Además, encuentran serias dificultades para compaginar todas las exigencias en los ámbitos personales y profesionales. Este grupo, en especial, tiende a presionarse por cumplir los estándares autoimpuestos para ser ejemplo, estar siempre bien y no quejarse. De igual manera, el cansancio psicológico, la culpabilidad y el miedo están presentes, de manera diferente pero no menos intensa, entre estos grupos de mujeres.

Mientras tanto, para avanzar sin esperar que cambien las leyes o que las organizaciones cambien totalmente sus estructuras y culturas, hay que iniciar el camino con cambios sencillos que, muchas veces, pueden hacer una gran diferencia. Establecer espacios para reencontrarse con la esencia del ser, despertar una consciencia más universal, conversar y escuchar sin prisa, sin juzgar, pedir ayuda, contar con otras mujeres, fortalecer los lazos de la amistad y de la solidaridad, crear pequeños grandes momentos, pueden hacer la gran diferencia. Cómo decía la escritora chilena Gabriela Mistral “Recordar un buen momento es sentirse feliz de nuevo.”

Las mujeres necesitamos mirar hacia dentro – en silencio – para escuchar lo que nos dice nuestro corazón y nuestra intuición, para crear una vida que tenga sentido para nosotras mismas. Cómo decía Jung en su última entrevista, “…necesitamos más entendimiento de la naturaleza humana, porque el único verdadero peligro que existe es el propio ser humano.”

A un nivel generacional, los adultos podemos parar la cadena de transmisión del “tengo que” a las niñas. Decía Sir Ken Robinson que “las escuelas matan la creatividad” innata de los niños. La escuela de la vida, en donde transmitimos a las niñas quienes tienen que ser, les mata su capacidad de vivir libremente, sin expectativas predeterminadas, sin recetas de éxito. Si les sumamos las grandes desigualdades que viven las niñas en los países en desarrollo, como América Latina, les transmitimos un insoportable peso de ser mujer.

“The Seven Sundays of the Week #1” in Córdoba, Argentina. Photo by Marisa Arce Zencich, who was chosen to participate in the DRCLAS digital exhibition, “Collective Isolation in Latin America: Documenting Covid-19 Through Photography.”

Si seguimos enseñando a las niñas que la primera vocación de la mujer será siempre la de agradar, les restringiremos drásticamente su espacio de realización personal. Los sentimientos ancestrales—el miedo, la culpabilidad, el cansancio—que continuamos transmitiendo impiden la individuación, un proceso esencial que reúne el inconsciente individual y colectivo para ayudar al desarrollo de la personalidad.

Todavía hay esperanza. Para ello, como decía Simone de Beauvoir, tenemos que aceptar la gran aventura de ser nosotras mismas y no sentir culpabilidad ni miedo en reconocer que estamos cansadas y que necesitamos ayuda.

Camelia Ilie Cardoza is Professor, Dean of Executive Education and Strategic Innovation, and President of the Center for Collaborative and Women’s Leadership at INCAE Business School. More than a thousand women have graduated from her-led programs in Europe and Latin America. She was a Visiting Fellow at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS) at Harvard University in 2019, and she will write a series of articles for ReVista under the title “Focus on Women” during 2021

Camelia Ilie Cardoza es Profesora, Decana de Educación Ejecutiva e Innovación Estratégica y Presidente del Centro de Liderazgo Colaborativo y de la Mujer de INCAE Business School. Más de mil de mujeres se han graduado en los programas liderados por ella en Europa y América Latina. En el 2019 fue Visiting Fellow de David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS) at Harvard University y este año va a publicar una serie de artículos en ReVista, the Harvard Review for Latin America—bajo el título Focus on Women.

Related Articles

Brazil’s Vaccinated Democracy

In March 2021, former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a current presidential candidate, posed a pointed question in a speech lambasting President Jair Bolsonaro’s Covid-19 response. “Where is our beloved Zé Gotinha?” Zé Gotinha is not a respected public health expert or crisis manager

Broken Land: Climate Change and Migration in Guatemala

Broken LandClimate Change and Migration in Guatemala Santos Istazuy Pérez (right) sits in meditation during a group hike and workshop at a lush farm along with fellow Guatemalans and like-minded people from around the world including Germany and Uruguay. Photo by...

The Gift of Art

My dear friend, Colombian pioneer performance artist, Maria Evelia Marmolejo, (Cali, Colombia, 1958) whom I met during the research for the exhibition Radical Women: Latin…