Firefly Dynamics

Catching the Bolivian Middle Classes

View from La Paz. Photo by Alejandro Loayza Grisi, Instagram: www.alejandroloayza.com

As the mestizo grandson of Bolivian Indigenous farmers and Scottish aristocratic landowners, I’ve long been fascinated by social mixing and mobility. Growing up in the city of La Paz, I was intrigued to see changes in the occupational and ethnic characteristics of people moving in and out of the areas where we lived. Families from outlying provinces, with historically poorer backgrounds, started to acquire properties and have access to businesses and leisure activities in neighborhoods traditionally inhabited by élite social groups. Fascinated by these firsthand experiences, I decided to focus my doctoral research on the Bolivian “middle classes,” how these had been redefined during the country’s history, and how their boundaries had been transformed in recent political times.

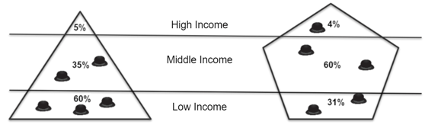

The shifts I’d observed in patterns of consumption and residence, in a country historically marked by profound inequalities, had to do with national economic growth and income redistribution policies introduced since 2006 by left-wing Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) governments. As you can see in the figure below, between 2005 and 2021, the proportion of Bolivia’s population with low incomes fell from 60% to 35%, and the proportion with high income fell in the same period from 5% to 4%. The result was a swelling of the middle income sector, which almost doubled in size (from 31% to 60%).

Source: Amaru Villanueva Rance based on data from National Institute of Statistics Household Surveys (INE, Encuesta de Hogares, 2017; 2021)

In our apartment block assembly meetings and virtual forum, I noticed that our neighbors didn’t mention “class” as a category of difference or belonging, inclusion or exclusion. They did talk about fair and transparent administration of bills and quotas, disputes about residents’ “proper” and “improper” behavior and conflicts among groups in wider society.

In my doctoral thesis (Villanueva Rance, 2021), I came to the conclusion that the Bolivian “middle class” was a figment of the imagination whose definition shifted constantly according to the interests of those describing it. During two hundred years of the country’s existence as a republic and then a plurinational state, mentions of the “middle sectors” or classes had popped up sporadically and disappeared from view for decades at a time. A key moment came in 1946 when Wálter Guevara Arze, a co-founder of the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR), proposed an alliance between middle classes, workers and rural farmers. Although this was not formalized, all these sectors participated in actions which led to the 1952 National Revolution and the MNR’s ascent to power.

In the 1960s, more attention was paid to the middle class, but no statistical research took place on it in this era. Between 1967 and 1982, there was a succession of military dictatorships that banned critical analysis of social issues. With the return of democracy, policy-makers adopted a development strategy of alleviating poverty and diminishing social inequality. From 1985 and during the next two decades, popular mobilizations resisted neoliberal structural adjustment measures, opposed privatization of gas and water resources, and defended Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Building in El Alto, Bolivia. Photo by June Carolyn Erlick

At the time of Evo Morales’ first government in 2006, support for the MAS had come from unionized sectors and popular organizations representing the country’s impoverished majorities. The rapid transformation in income distribution had effects on the profile and interests of the party’s traditional base. However, despite improvements in their socio-economic status, references to class-belonging were not apparent in the popular masses’ spontaneous, everyday language and self-positioning.

Nevertheless, political and social analysts were highly interested in the topic of class self-identification, and they explored it in national surveys that formed part of global research programs. A surprisingly high proportion of Bolivian respondents, when asked to choose between pre-defined class categories, declared that they belonged to the middle class, or to some group within that sector. The World Values Survey, in its seventh wave (2017-20), found a world average of 57% middle class self-identification. In the Latin American region, Bolivia stood out with a level of 66%, while Argentina had 59%, Peru 58% and Brazil 33%. According to another major survey (Latinobarómetro, 2020), 79% of Bolivian respondents self-identified as middle class, again ranking higher than Argentina (70%), a country traditionally referred to as a middle-class society.

Putting findings from my research together with these results, I sensed some kind of split in understanding between people’s everyday indifference to social class as a feature of self-definition, and their readiness to sign up to middle-classness if pushed to opt for a label. What could it mean to identify consciously with a middle sector? In terms of belonging, it could signify feeling part of a recognized majority in society, neither élite and privileged, nor poor and excluded. In ideological terms, it could be an expression of leaning towards the center of the political spectrum, thus distancing oneself from extremes or forms of radicalism.

Going from the perspective of those analysed to that of the analysts, some commentators referred to the middle sector as a cohesive block, while others used labels of internal stratification such as upper, middle and lower-middle class. Debates grew about whether attributes labelled as typical of the middle class had more to do with income level, types of occupation, cultural and educational background or patterns of consumption.

Looking more closely at politicians’ declarations over time, I saw that Evo Morales had traditionally referred to the Bolivian middle class in dismissive terms. In various speeches, as president, he cited sociologist Sergio Almaraz who called it a “clase a medias,” a half-baked class (Morales Ayma quoted in Maldonado, 2014; Morales Ayma, 2014, 2016). It was therefore surprising how Morales revised his position in January 2018, after a series of significant political events and mobilizations, “We need to improve, look into and gather the aspirations of the new middle class” (Morales Ayma, 2018). In that same month, former president Carlos Mesa, an opposition leader highly critical of MAS, published an article in which he portrayed the middle class as “an idealized space” towards which all societies should head (Mesa, 2018). In turn, Morales’ vice-president Alvaro García Linera outlined his position in a newspaper article, remarking that this large grouping—made up by over half of the country’s population–was divided into two bands: “decadent” traditional groups, and “new” groups (García Linera, 2018).

Man at Work. Photo by Iván Rodríguez. Instagram

In this same period, some MAS leaders pointed to a need to look for the middle-class vote once more, suggesting that they had ignored this group of the electorate. Two leaders talked about this class as if they were an object of romantic desire. Victor Borda, then policy chief of the MAS parliamentary bench, said that it was necessary to “win them over” again (reconquistar a la clase media). The then vice-minister of Coordination with Social Movements, Arturo Alessandri, spoke of going back to court (volver a enamorar) the middle classes. Moving into the debate, some opposition leaders argued that public policies had abandoned the middle classes. It is difficult to tell how judicious it was for political strategists to seek votes from a middle class that was extremely diverse and undefined, and more imaginary than concrete.

During the years following the November 2019 coup d’état orchestrated by national and international players, different analyses were published on the political situation, some bringing the question of the middle class back into discussion. In reviewing a group of press articles and books published since that date, I can identify a context marked by two different types of crisis. On the one hand, convulsion marks the period of the Jeanine Añez administration because of its lack of legitimacy, manipulation of repressive state apparatus to pursue political opponents, and readiness of social organizations to demonstrate against those in charge of government. On the other hand, the health crisis provoked by the Covid-19 pandemic has absorbed public attention as Bolivians faced quarantine, limited access to medical supplies and services, variable uptake of and compliance with preventive measures, and effects of the above on the economy, particularly in the informal sector.

Some MAS representatives—including leaders I interviewed for my doctoral research in 2018-2019—have expressed concern and even self-blame regarding some decisions taken by the party in its periods of government and during the 2019 electoral campaign. Areas they touched on as problematic included reaching out to the middle classes, trying to occupy the political center, leaving the popular masses to one side, and pursuing success through “growth of the middle classes.” The epitome of anti-MAS antagonism was identified in a vocal middle-class sector known as “pititas”—a term first used to ridicule these anti-government demonstrators as racist and elitist, and then defiantly taken on as a label by the demonstrators themselves.

Street Scene. Photo by Iván Rodríguez. Instagram

I identified moves taken by MAS to create, embrace and then devalue the real or imagined constituency of the middle classes. First they brought it into being by pulling the majority of the population out of poverty. Then, they paid attention to the newly-emerged center of the electoral mass and courted its occupants. Next, they heard the voices of historic MAS affiliates who felt relegated when the middle classes were explicitly taken into account. They then shed doubt on middle-sector reliability and cohesion. Finally, they ignored middle sectors (not affiliated to unions or popular organizations) in policies to redistribute power and employment quotas. They achieved this last step by regrouping party ranks and leadership around social movements, and concentrating resources on sectors that had traditionally been loyal to MAS. This was their strategy, rather than reaching out to indecisive or undefined elements of the newly configured electorate.

I could read internal splits in politicians’ oscillations between assigning negative and positive attributes to the Bolivian middle classes. They expressed this ambivalence in public declarations that these influential sectors were worthy of campaigning attention, without taking steps to follow through by introducing concrete policies in their favor. What grabbed my attention in this era was the emotive character of politicians’ expressions regarding the middle classes. Representatives of different parties started referring to this sector less in terms of statistics and demographics, and more in discourses that swung between attraction and repulsion, love and hate. The topic’s popularity grew when leaders reassessed their potential allies and opponents, during electoral campaigns, and throughout the highly-charged period of the 2019 coup d’état and fall-out from the authoritarian Añez administration.

This dance of off-on switches between strong emotions of repulsion and attraction between the middle classes and MAS as legitimate or desired partners, reminded me of a popular Andean cumbia entitled Luciérnaga (firefly), whose lyrics say:

I, like them all, believed in you, and I got lost in your eyes / Firefly, firefly / How you light up and go dark, all the time. / Firefly, firefly / Come back one day when you’ve learned how to love.

I visualized a love-hate relationship being engendered between the MAS and those social actors, so hard to grasp, and for that very reason, perhaps, so enigmatic in the way they could be attracted by—and attract—electoral and political proposals. The pendulum is now swaying away from a focus on the middle class, and swinging back to MAS concentration on popular social sectors that have been its traditional base. When and how the pendulum will return to focus attention on the middle class—and how its boundaries will alter in new economic contexts—is a question for the future.

Amaru Villanueva Rance is a Bolivian/British sociologist with a Ph.D. from the University of Essex. He has a B.A. Hons. in Politics, Philosophy and Economics and an M.Sc. in Social Science of the Internet, both from the University of Oxford. Amaru currently lives between La Paz and London. This article was written with the indispensable help of Mario Murillo and Susanna Rance.

Related Articles

Slavery Upstairs, Slavery Downstairs

On February 14, 1800, someone slipped an anonymous letter to the solicitor general of Lima’s high court via one of his domestic servants. When he opened it, the solicitor (fiscal)…

Let’s Talk about Resilience

English + Español

When I joined the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) family in October 2019, I never imagined that a few months later I would experience both the pain and…

Qualified but Rejected

English + Español

As of 2021, more than six million Venezuelans had left a crisis-ridden country in search of a decent life that is not plagued by food insecurity and the lack of other basic needs. Close to five million of them…