First Take: Never Again

A Photoreflection

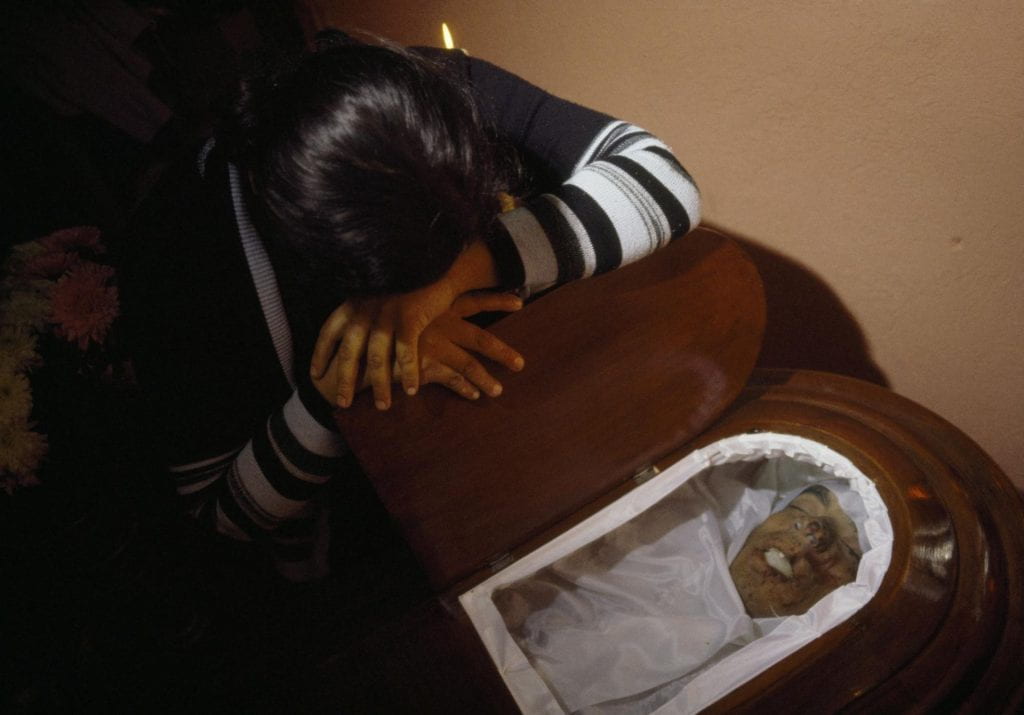

Wake for Hector Gomez Calito, founding member of Mutual Support Group for the Families of the Disappeared (GAM), Amatitlán, 1985. Photo by Jean-Marie Simon

I traveled to Guatemala for the first time in late 1980, believing, with the breezy confidence of a 20-something, that my photographs of Guatemala’s war—army, guerrillas and terrified civilians—would bring me photographic stardom. Soon afterward, I imagined, I would make my mark in Serbia, Panama or wherever as Girl Globetrotter. Despite my cocky assumptions, I was not naïve regarding Guatemala’s pariah human rights status. I had read the requisite human rights reports, acquired triple-A contacts, and even got a letter from my parish priest, pronouncing me a practicing Catholic. When I landed at Guatemala City’s Aurora Airport just before Christmas, the soldiers on the runway and the intelligence agents doubling as customs officers already existed in my imagination.

What surprised me, however, were three realities I did not foresee: the challenge of taking pictures in a country where almost no one wanted to be photographed; the apathy of U.S. newsrooms with respect to Guatemala; and the difficulty of putting a face on terror.

The first circumstance—dealing with a list of contacts who did not want attribution in a caption, much less a photo of themselves in the newspapers—was at first discouraging, particularly when my colleagues in El Salvador described how they would go out with the FMLN guerrillas and be back the same day, in time for cocktail hour.

The reason for the second circumstance was transparent: Guatemala was the third player in a triptych of events that, by 1981, editors back home viewed as the latest in an amorphous regional blur. The overthrow of Somoza in Nicaragua, followed by massacres and the death of Archbishop Óscar Romero and four U.S. churchwomen in El Salvador precluded any reporting on Guatemala, as these events were dramatic and directly tied to U.S. political and economic interests

The third element was the most unnerving: at first blush, Guatemala seemed normal. Planes to Miami and L.A. departed like clockwork, Christmas vendors were out in full force, and pre-dawn firecrackers announced birthday celebrations. Even outside the capital, travel was not impossible: American Express continued its excursions to the Chichicastenango market; hippies sold bird-sound cassettes on Calle Santander in Panajachel; and Time magazine ads trumpeted the magic of Tikal’s Mayan ruins.

At the same time, however, Guatemala was riven by irrefutable, state-inspired violence: “civil war” to some and “internal armed conflict” to others. Amnesty International, in 1981, accused the military regime of overseeing a “government program of political murder.” Normalcy, moreover, was skin-deep because Guatemala was living in an undeclared state of terror. U.S. flights took off and landed, but they were nearly empty; those birthday firecrackers were indistinguishable from machine-gun fire; and films with a liberal political slant were de facto forbidden. In 1983, when the Cine Capitol showed Missing—the story of the abduction and torture of U.S. reporter Charles Horman, during the 1973 military coup in Chile–a professor friend joked that Guatemalans were so hungry for such movies that the army could have eliminated half the urban guerrilla leadership by dropping a bomb on the opening night at the movie theatre.

Moreover, and in some ways worse, I became accustomed to this climate of terror. It was normal for friends to have a pseudonym, or even two. It was tantamount to an insult if your telephone was not tapped, since it implied that your work was cursi, or useless. And even newcomers to Guatemala soon learned how to interpret the news: “delinquent” meant guerrilla and “disappearance” meant extrajudicial kidnapping. In truth, the only news related to the constant kidnappings during that time were paid announcements published by the relatives of the victims: fuzzy black and white photographs paired with a terse description of the victim and the assertion that he or she had no political connections.

Perhaps the most insidious truth about living in Guatemala during the 1980s was its effect on relationships with your colleagues and even family, and the gnawing doubt it inexorably created with respect to whom you trusted, including your most intimate circle of friends. Guatemalans wondered aloud if the person plucked from the street at midday, by plainclothes men with rifles, could be a common thief, or whether the young professional forced into a Jeep without license plates had committed a crime. ¿A saber en qué estará metido?–“Who knows that he might be mixed up in?—was the mantra.

Between 1980 and 1989, when I lived in Guatemala, my goals changed; the idea of being a rock-star photographer faded as I did more interviewing and consulting along with the photography. I went on contract to Human Rights Watch and wrote four human rights reports, among other endeavors. Although the rewards were initially more unpredictable—one month it was Time, the next it was Maryknoll magazine; a Finnish film crew in September, 60 Minutes in December—they were fulfilling. I went from wanting kudos in American Photographer to wishing to be useful on the ground. I also realized that what I was photographing had its limits in the United States. When I took my photographs to National Geographic in 1986, the photography editor told me that my photos were too “one-sided.” “Keep shooting,” he advised. “Show us the other side of the coin.” Although I knew what he was saying, I felt like Robby the Robot: “Does not compute.” I kept taking photographs of the Guatemala I lived in, and realized that the only way to show “my side of the coin” was to do a book.

Now, with the Spanish edition of my book, Guatemala: eterna primavera, eterna tiranía, my photos have almost come full circle. The next project is to do a cheap, pocket-book edition of the book with 200 color photos and to price it at under $15, with a 5,000 print run.

The question I perhaps most often heard when the book was launched, in Guatemala, this summer was: “What has changed?” Well, in some ways, a lot. You can be a leftist politician without getting killed. You can teach at the San Carlos University without being gunned down on campus. You can spray-paint graffiti on a wall without signing your death warrant. And bookshops like Sophos exist, where, if you have the money, you can buy a basket full of paperbacks of every political ilk. People whose grandparents were the poorest of the poor now send money home from Miami and Houston and build houses with electricity and full-length mirrors. And, once in a blue moon, a miracle: Bishop Juan José Gerardi’s murderer stood trial, and one of those responsible for the Dos Erres massacre has been arrested. This is all progress of one kind or another.

At the same time, however, little has changed: there have been no investigations into the great majority of political crimes and, with few exceptions, those responsible go unsought and unpunished. In addition, Guatemala now faces another kind of terrorism, one where violence and narco-trafficking are inseparable pandemic evils. To be a bus driver means risking your life, and getting on a bus is almost as large a risk. And in the midst of this new violence, poverty and corruption–two inextricably bound realities–continue to dominate, front and center, Guatemala’s economic and political landscape.

People also ask, “Why don’t you offer a solution? Your photographs hold no answers.” True enough; my photographs do not attempt to offer either profound thoughts with respect to the past nor solutions to Guatemala’s present. At the same time, however, and perhaps their greatest value, is that they were taken before the era of Photoshop, before you could change the truth with the click of a mouse. In other words, they do not lie.

SEE THE FULL PHOTOESSAY HERE.

Jean-Marie Simon’s original book, Guatemala: Eternal Spring, Eternal Tyranny (WW Norton, 1988), recently re-issued in Spanish as Guatemala: eterna primavera, eterna tiranía, contains over 150 color photographs, including 50 previously-unpublished images. Her book is available through Amazon.com. It has been nominated for the 2010 Wola-Duke Book Award. Simon is a graduate of Georgetown University and Harvard Law School (JD 1991) and a former Fulbright scholar. She lives in Washington, DC, with her husband and their daughter.

Related Articles

A Beauty That Hurts: A Photoessay by Carlos Sebastián

A Beauty That Hurts A Photoessay Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1 Related Articles

Cyclones of Violence: A Photoessay about Determination and Survival

A Photoessay about Determination and Survival

Revitalizing Mayan Textiles

English + Español

What satisfaction could be greater than the joy of sharing the completion of one’s first weaving? None! This pleasure is even greater when the weaver is a young boy or girl, facing for the first time the challenge of…