First Take: The Political Geography of Water In a Changing Brazil

A young man gazes out at the water in Salvdor da Bahia, also in northeastern Brazil. Photo by Cristina Costales

“One must begin with water,” wrote the historian Fernand Braudel, because the provision of water services is one of the foundations for civilization. People and societies want protection from floods and droughts; they want water to drink, to irrigate their crops and to produce clean energy. Brazil is a case in point for how one country has used water as a platform for economic development, with its successes, failures and current challenges. A hydrological overlay corresponds closely, as Braudel might have expected, to broad economic regions.

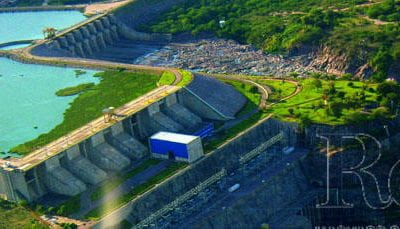

The South and Southeast, the economic heart of modern Brazil, are blessed with abundant and consistent supplies of water. The country’s industrial development was built on the basis of cheap (and clean) hydropower, mostly at a very large scale—the Itaipu Dam on the Paraná River produces more electricity than any other dam in the world. Over the latter half of the 20th century, most of the economically viable hydropower in this area has been tapped. Hydropower does not, of course, consume water, but rather takes advantage of its flow. Thus, the regulated rivers of the South and Southeast also provided a reliable and abundant supply of water for the growing megalopolises of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, as well as this region’s many other large and small cities.

The availability of abundant water is, however, just one part of a supply chain needed for a healthy urban life. Surveys in São Paulo have shown the dynamic of challenge and response and the hierarchy of demands for a growing economy. Fifty years ago, “clean water” was the highest priority for the burgeoning favelas. This need was met both through economic growth and political voice, only to be followed by a demand for getting wastewater out of the house and neighborhood. This challenge, too, has largely been met, and the challenge for the cities is now the drainage of storm water, treatment of wastewater and improvement in the quality of rivers and estuaries. Accompanying these efforts have been gradual changes in the institutions for managing water. In the days of the 1950s “Brazilian miracle,” the approach was state-driven and centralized. Much was accomplished, but the water institutions were largely unaccountable and inefficient. Within the context of the maturing of the Brazilian economy, water institutions too have changed. The Brazilian water utility SABESP, the fifth largest in the world, has evolved into a hybrid institution, half-public, half-private, that is charting a new and promising path for reconciling social accountability and efficiency in Brazil and elsewhere. The consistent and moderate rainfall in this region has also underpinned the development of Brazilian biofuels, with entrepreneurial farmers and quality scientific research meaning that Brazil can rely on ethanol as the primary source of energy for its transportation network.

At the other end of the hydrological and economic spectrum is the Northeast, where water has always been both scarce and unreliable, giving rise to endemic poverty and a paternalistic “culture of drought.” The great response in this region—one followed, amongst others, by President Lula—was migration away from hydrological-induced suffering to the favelas of the Southeast. But attempts have also been made to use the ample waters of the São Francisco, the one great perennial river of the region, to build a water platform for growth both within the São Francisco Valley and in the arid hinterland. Again the dominant feature has been the capture of the large hydroelectric potential of the São Francisco, providing cheap and clean power to the regional economy. Efforts to use the waters of the river for agriculture within the valley have been persistent, but of limited benefit. Some successes with private farmers irrigating high-value crops have been offset by persistent failures of large public irrigation projects to kick-start the regional economy. Learning from these successes and failures, Brazil is now experimenting with new models of public-private irrigation partnerships, which, it is hoped, will bring dynamism but also a broad-based distribution of benefits. Beyond the basin, the great temptation has always been to see a pipeline from the São Francisco as the solution to the endemic water insecurity of the arid areas of the Northeast. After decades of discussion, such a pipeline is now being built, in an effort to find a new security equilibrium for the “drought polygon” to the north. Necessary as the infrastructure is, the great challenge—yet to be squarely faced—is what software (allocation and management instruments) will be put into place to realize the promise of a very large investment.

The third great hydrological region is the Center-West, a savannah once considered impossible to cultivate but now the heartland for the world’s largest production of soybeans. Brazil’s decades-long investment in agricultural research has been the key, but so too is the relatively even and consistent rainfall that waters these vast plains.

The fourth great hydrological region of Brazil is the Amazon, home to the world’s biggest river and largest forest. Until recently, the Amazon and its tributaries were primarily a barrier to development. But this is changing, because of two big national drivers. The first is the massive hydropower potential of the Amazon and its tributaries. Large as the installed hydropower capacity of Brazil is, twice this potential still exists in the Amazon. Some early attempts to develop this power were disasters, with huge areas submerged for little energy return. As environmental concerns have risen in Brazil, so designers have innovated, with current-generation projects having a footprint per unit of energy just 1/100th that of earlier projects (albeit at the cost of lower reliability of energy supply). The second driver is the need for cheap, environmentally friendly transport of grains. Despite having two of the great river systems of the world (the Amazon and Paraná), Brazil ships only about 15 percent of its grains by river transport (in comparison to 60 percent for the United States). River transport, unlike roads, does not lead to deforestation and thus developing Brazil’s internal waterways is a high priority for the country.

Panglossian as this picture is,two great unknowns and potential threats endanger Brazil’s water security. The first of these is the effect of land-use and vegetative changes. A big mystery is why the runoff of the Paraná River has increased by almost a third in recent decades. It is generally assumed that this must be due to land-use changes in its catchment, but there is little science to support this thesis. Looming larger still are questions about the potential impact on the hydrology of the plains of changes in the Amazon forest because of both climate change and deforestation. Every year about 12 trillion cubic meters of water fall on the Amazon forest. About half of this runs back to the ocean in the rivers, but the great forest re-evaporates half, and 6 billion cubic meters (10 times the flow of the Mississippi) gets blown onto the Andes, with the clouds then sweeping down and raining on the plains of Brazil and Argentina. Whereas rain in the United States and Europe comes almost entirely directly from ocean-based evaporation, in South America it is this land-based evaporation which drives the hydrological cycle. Whence a great question: what will happen to the hydrological cycle when, due to climate change and deforestation, the vegetation of the Amazon region changes? What will be the impact on the great green sources of electricity (hydro and ethanol)? What will be the effect on Brazilian agriculture and even on the water-dependent cities?

Last, of course, is politics. People looking from the banks of the Charles River in Boston may raise eyebrows at the “sustainability” of all of these achievements. And indeed the usual celebrities—from James Cameron to Bill Clinton—make the usual lofty statements about their opposition to dams in the Amazon, and the U.S. government finances international and local NGOs to build opposition to these priorities of a democratic government. But Brazil, like China and India and a growing group of middle-income countries, no longer have to bow at these altars—the Brazilian Development Bank is three times the size of the World Bank. At the end of eight years in office, President Lula had presided over extraordinary changes in his country, both in making (in his words) Brazil into “a normal country,” no longer subject to populist politics, and in consistent growth, especially for the poor. President Obama described him as “the world’s most popular politician.” And what was Lula most proud of? The first items in his farewell speech to the nation had to do with infrastructure, especially the hydro plants of the Amazon and the São Francisco inter-basin transfer. Building a water platform for growth and securing Brazil’s water-related security is indeed a great achievement, but as is always the way with water, successes give rise to new challenges which will test the ingenuity of the next generation of Brazilian political and scientific leaders.

John Briscoe is Gordon McKay Professor of the Practice of Engineering and Environmental Health at Harvard University, where he directs the Harvard Water Security Initiative. He teaches undergraduate and graduate courses on water management and development.

Related Articles

Al Son Del Río

English + Español

Wending our way down the Atrato River in Colombia’s Chocó region, we finally reach the town of Puné. It is a fickle June afternoon, one of those humid tropical afternoons when the sun and water alternate in sudden torrential rains. “The river is everything to us,” …

Water: The Last Word

A man was shot and killed in a dispute in June 2010 over a water connection in San Juan Cancuc, Chiapas, Mexico. A Zapatista settlement coexists, if uneasily, on the edge of the municipality. Residents of the nearby community of El Pozo had threatened to shut off Zapatistas water connection. A confrontation ensued, shots followed, with one fatality and nine wounded. …

Water, The Energy Sector and Climate Change in Brazil

As a Brazilian, I am very proud of the rich natural resources of my country, in particular water resources. As an engineer who had worked in the Brazilian energy sector for the last fourteen years, I am very proud of the infrastructure built over the last seventy years that has allowed the use of water resources responsibly and intelligently. But as a hydrologist and doctoral student in water resources,…