First Take: Two Tales of Mining and Human Choice

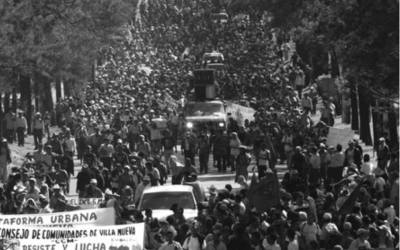

A Chilean miners’ labor union mural (1999 near La Serena in Andacollo, Chile. Photo by Louie Palu/Zuma Press.

Two tales of very small human settlements with mining potential may help us reflect on what Latin America, on a larger scale, faces today regarding the exploitation of minerals from its territories. At these two settlements, mining was stopped because of human choices and collective action. In one case, tensions led to the use of force and rebellion; in the other, environmental tensions led to deliberation and democratic practice. Both illustrate the never-ending controversies about mining that have been haunting our continent in past centuries and to this date.

One of the stories, on the small island of Navassa in the Caribbean, ended in the death of some workers, the jailing of several people and the suspension of the collection of guano, a natural fertilizer highly valued toward the end of the 19th century at a moment when the U.S. agricultural sector was in great need of improving its farming productivity. The other case took place in 2013 in Piedras—a small town in Colombia’s highlands—where the plans of a major international gold mining company to extract around a million ounces of gold per year over a twenty-year period are now stalled, while raising the hopes of a community that feared the threat of gold extraction would ruin their health, water sources and agricultural activities.

Both stories might be used to reflect on the current prospects of a new wave of mining in the region, brought by an increasing world demand for minerals. This boom brings fears of social and environmental negative impacts on the one hand, while on the other, it promises substantial revenues for states that urgently need to reduce poverty, now that most Latin American countries have embraced democracy and social redistributive policies.

There lies the dilemma of a curse or a blessing, mining as a source of conflict and tragedy, or mining as a means for improving the well-being of the majority through fiscal revenues and social investment. The following two stories lie at the extremes, and as such, they should invite a constructive policy debate for the region.

THE GUANO STORY ON NAVASSA ISLAND

On his fourth trip, part of the crew traveling with Christopher Columbus landed on this small island between Haiti and Jamaica, and found no water, probably the main reason why there was no interest for the next three centuries in this five-square-kilometer piece of land. In mid-19th century the United States enacted the Guano Island Act (1856), which allowed U.S. citizens to take possession of unoccupied islands where guano was found and where no other countries had declared jurisdiction. The demand for guano, a precious fertilizer at the time, was booming with prices ranging between $50 and $70 per ton.

In 1857 Peter Duncan claimed Navassa under this act, later transferring his rights to Edward Cooper who then sold them to the Navassa Phosphate Company of Baltimore. This company exploited the guano under the direst of working conditions with a group of between 140 and 180 African-American workers brought from the Baltimore area. Mining started by the mid-1860s, with each man digging up between one and one and a half tons of guano per day, while being paid around $8 per month.

By 1889 half of the workers were not allowed to go back to Baltimore because of their debt with the company store on the island, which charged more than they could pay with their earned wages. The levels of physical punishment and inhuman working conditions ultimately led to a riot that year, ending with the death of five supervisors, and trials and execution sentences for the miners in the United States. The company declared bankruptcy in 1898 as a result of its bad publicity, difficulty in hiring workers and competition from other fertilizer suppliers. In 1901, the short-lived mining project in Navassa was shut down.

THE “CONSULTA POPULAR” IN PIEDRAS, COLOMBIA

In May 2013, the municipal council of Piedras in the Colombian Andes decided to issue a popular referendum, known in Colombia as consulta popular. The question was whether the inhabitants agreed that the municipality should allow extractive activities that could harm the health, water supply and agriculture of its territory. This particular town is at the center of a controversial mining project (“La Colosa”) with estimated reserves of 24 million ounces of gold, worth more than $US30 billion today, and managed by one of the world giants of gold mining. The area affected is part of a particular ecosystem providing water sources for an entire region highly dependent on irrigation for rice production and human consumption. The project, according to the company, would cover 3,953 acres. Rough estimates mention state revenues between royalties and taxes of around USD$450 million per year during the length of the extraction project.

On July 28, 2013, this small municipality of 14,200 inhabitants voted on the referendum. For this vote to have legal validity, a minimum of 1,702 votes was required. A total of 2,995 valid votes were finally cast. Only 24 gave a “yes” to mining, while 2,971 votes (99 percent) for the “no” sent a clear mandate from the local level, expressing the direct will of the people.

However, here as in all Latin America, the subsoil belongs to the national state and not to the landowners sitting on top of the valuable resources, creating a challenging jurisdictional dilemma. The company expects to begin production by 2019 on what would become the largest gold mine in Colombia, but as of today it still needs to muddle through several legal pending issues regarding environmental licenses in addition to this popular referendum, all of which has created a predicament for the national government.

LESSONS LEARNED, AND NOT LEARNED

These two extreme outcomes illustrate the tensions associated with mining, and should thus offer some lessons for reflection. It is not easy for the state to forego valuable and often urgently needed revenues for reducing poverty in order to preserve cultural systems, biodiversity-rich ecosystems, water supplies, and to reduce the threats to the health of local inhabitants. At the same time, to carry out extraction under inhuman or unsustainable conditions for highly profitable short-term profits is an unlikely prospect and seems to be a thing of the past. However, the excessively high profits from extracting some of these commodities can create small mineral rushes—just as with gold or colombite-tantalite (or coltan) today—in many of the peripheral areas out of control of the state, offering opportunities to informal miners and illegal groups. In Colombia, for instance, guerrillas, paramilitaries and other armed groups have turned their attention to gold as a more profitable source of revenue than drug trafficking.

Where such remarkably high profits are available, there will always be entrepreneurs willing to take the risks of investment, and therefore extraction, legal or illegal, small or large scale, will follow.

The century that elapsed between the events at Navassa and Piedras witnessed the arrival of legal mechanisms for workers to demand more decent conditions than those faced by the African-Americans who travelled from Baltimore to Navassa in the 1860s through the 1890s, or the Chinese workers in the guano mines of Peru. Progress in environmental laws and awareness has opened more opportunities for civil society and authorities to stay vigilant to the possible risks brought by these extractive activities and even exercise their right to stand against mining entirely. International agreements such as Convention 169 to protect indigenous and tribal lands have also pushed for changes in the national legislations that regulate mining activities, while the increasing mobilizations by rural communities and indigenous tribes against extractive industries continue to confront the industry.

Although local communities have better legal and democratic mechanisms today to oppose projects if they wish to, this does not mean that such mechanisms are without controversy or are always successfully enforced. But they do exist and are being more frequently called upon to defend the interests of those endangered culturally, environmentally or economically because of the threats from extractive activities.

However, the boom in mineral prices in the last decade has brought an equivalent increase in demand and therefore in potential rents, changing the landscape for the rule of law. This price hike in commodities such as gold since 2000 is extraordinary. Not even the small gold boom in the early 1980s could compare to the high prices of the last few years.

When prices in the international markets send such strong signals, risks and threats will also thrive. That was the case during the Guano Rush in Peru and on numerous islands as carefully described in the book by Jimmy M. Skaggs, The Great Guano Rush: Entrepreneurs and American Overseas Expansion (St. Martin Press 1994). Increasing demand for coltan and other high-priced minerals will also bring these fears and opportunities.

THE LEGAL CONUNDRUM: RIGHTS BELOW AND RIGHTS ABOVE THE LAND

When informed and empowered civil societies enjoy a transparent private sector and effective and honest governments, dilemmas about mining can be solved through fair negotiations. This methodology creates opportunities for the mining sector while guaranteeing that economic benefits are spread evenly, and that environmental and social impacts are minimized.

However, there is still an institutional puzzle to be solved in the case of Latin America and its mining regulations. The problem is the dispute between the rights of the land where the mining projects are located and the rights over the subsoil. Because of historical reasons that date back to Castillian law and its subsequent laws for the “Indias,” national governments in the region have declared the resources of the subsoil of national interest and therefore these non-renewables remain under the ownership of the state.

Meanwhile, rights over the land have evolved towards guaranteeing private property through land reforms and legalization of the historic occupation of land, while also recognizing the rights of ancestral, Afro-descendent or indigenous groups over their lands through collective titles. Better legislation regarding the protection of forests, biodiversity and water resources has also helped to clarify and guarantee the common interest over the private interest when activities around the land threaten the sustainability of life and society. At the same time, the gradual and continuing process of decentralization from national to regional and local state levels in Latin America has empowered citizen-voters to get closer to their local public affairs. This has created regional and local movements that often collide with the political agendas or priorities of their national governments.

The continuation of the tradition to control and own the minerals and fuels in the subsoil for the national interest has provided governments with important sources of revenue, opening possibilities for social investment but also for corruption and the emergence of less democratic leaders. It is certainly easy to understand that no national government would forego such a rapid revenue checkbook. But it also needs to be recognized that the coexistence of state ownership of the subsoil with a more empowered civil society, stronger constitutional rights about the environment and cultural diversity, along with private and collective property rights over the land, will bring additional conflicts for designing and implementing any kind of mining activities under it.

Mining is bound to harm the socio-ecological integrity of the land where the extraction is to happen, often exacerbated by the additional infrastructure required for the mining operation such as roads, water supplies or disposal of material. These activities often bring undesired side effects through the colonization of forested lands and expansion of the agricultural frontier. The trade-off is quite clear. The benefits of mining will have to come at a cost to the environment, agriculture and the integrity of the cultural systems in the location of the mining project.

The tale of Navassa could have had another ending, if more humane conditions of work were put in place and the distribution of benefits was closer to fair, allowing the Navassa Phosphate Co. to seize the opportunity of a great business that was closer to the eastern coast of the United States. At the time, Peru was facing serious political and economic problems and finding it difficult to maintain its prominent role as a major supplier of guano. A missed opportunity indeed. The future scenarios for the “Colosa” gold mining project in Piedras are still to be written, while the company and the environmental authorities resolve pending legal issues regarding licenses and impact evaluations, and while the judiciary deals with the extent to which the popular mandate of the voting in Piedras collides with the legal conundrum of the ownership of the subsoil by the national state.

Latin America does not have to face more Navassas, as more democratic institutions offer today more civilized spaces to exercise the right of people to intervene in their local public and private affairs, as was shown in Piedras. The trade-offs between minimizing the socio-ecological impacts and generating revenues for the state and private sectors can be solved through deliberation and the rule of law, but the main legal and political challenge in Latin America regarding the rights over the land and the rights to the subsoil remains.

Winter 2014, Volume XIII, Number 2

Juan Camilo Cárdenas is a professor in the Economics Department at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. He was a Robert F. Kennedy Visiting Professor of Latin American Studies at Harvard in 2007-2008.

Related Articles

Making a Difference: Building Blocks

Since the first, unplanned visit of a Brazilian entrepreneur in 2011 to Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, a diverse group of professors, practitioners, civil society leaders and other committed individuals at Harvard and in Brazil have…

Travails of a Miner, VIP-style

English + Español

Sergio Sepúlveda is a Chilean miner with an enviable salary—equivalent to that earned by a university-educated professional. He owns a brand new Korean-made car, and every three years…

Indigenous People and Resistance to Mining Projects

English + Español

Latin America’s governments and its indigenous peoples are clashing over the issue of mining. Governments, motivated by economic growth, have established legal frameworks to attract foreign investments to extract mining resources. When those resources are located in…