About the Author

Carla Troconis graduated with a BA in Government from Harvard in 2019 and wrote her senior thesis on the participatory patterns of the Venezuelan diaspora in South Florida. She is a proud Venezuelan immigrant who hopes to use her varied skills and background to bring awareness to the horror back home and tell stories of the Venezuelan diaspora in all its complexity. Currently, Carla is working as a writer and filmmaker and is releasing her first documentary, DIASPORA, in Fall of 2019.

Five Weeks in Doral, A Lifetime in Crisis

I arrived in Doral, Florida on May 13, 2018. It was the earliest I had ever left Harvard for the summer. Usually, I liked to stick around, relax after finals, and watch friends of mine graduate and leave for their adult lives. This time around, however, there was a pressing need to get out of Cambridge. I had been approved for political science thesis research and a documentary project for Alfred Guzzetti’s famed “Nonfiction Video Projects” class—both exploring the Venezuelan diaspora.

For five weeks, I rented out a small studio and focused on conducting political interviews with and capturing footage of a range of Venezuelan immigrants living and fighting against the Maduro regime in South Florida. The individuals I met and the stories they told me shocked and moved me more than expected. As a Venezuelan immigrant myself, my exposure to the current political crises has spanned my entire life. Yet the Venezuelan diaspora in South Florida is more diverse and more complicated than I could even imagine. Above all, the Venezuelan diaspora is a community in crisis trying its best to combat the dictatorial demise of their home while forging deep cultural bonds in a nation that oscillates between pretty rhetoric and nasty action.

As I frequented countless arepa restaurants and one opposition march after the other, I quickly met a young protestor named Juan on May 20th, the day of the highly contested Venezuelan presidential elections, a key site of global protest was Miami, Florida. In the mass of impassioned protestors, faces contorted in the cries for help they had rehearsed at protests in the past, stood Juan—unmoving, gaze steely, and holding a poster board with roughly twenty printed names and dates arranged neatly over it. Later in conversation, Juan told me that those were the names of his twenty closest friends and fellow student protestors in Venezuela, all of whom had died as a result of government oppression in 2017. One of the only survivors in his friend group, Juan fled Venezuela after the massive wave of violent student protests in 2017, crossing alone first into Colombia and working any jobs he could until he could afford a plane ticket to Miami. Now, he lived in Doral, biding his time until his asylum hearings, which he assured me would go successfully. Every day, Juan woke up at five-thirty, piled three recently purchased winter coats onto his arm, and walked to the flower plant he worked at. There, he and other undocumented Latin Americans, mainly from Venezuela and Colombia, would lift heavy boxes in sub-freezing temperatures until roughly six in the evening. As Juan described his day to day routine, he would often downplay the difficulty and pain of his life as an undocumented Venezuelan by saying it would all be resolved once he was granted asylum. The majority of Venezuelans fleeing to the United States are trying their luck the same way Juan is: by applying for political asylum. In the meantime, they live as undocumented immigrants in a country quickly becoming more aggressive and hateful towards them. While listening to Juan and others I would later meet like him, the irony of their situation began to make sense in my head. The Trump administration’s recent anti-immigrant rhetoric and cruel human rights abuses against immigrants painted a clear picture to Latin Americans arriving in the United States that acceptance and assimilation is not in the cards for them. Yet, on the other hand, President Trump and Vice President Pence’s enthusiastic lip service to the Venezuelan community have created the illusion that Venezuelans, much like the Cubans that preceded them, are a protected class of Latinx immigrants. Pushed by ideological preference and often ignoring the nitty gritty details of the social, political, and economic situation in Venezuela, our current President has assuaged incoming Venezuelans that they are a special breed of immigrant whose status will be quickly presented if and when an asylum proceeding is carried out. The key, however, in the midst of Trump’s immigrant directed hypocrisy is that asylum laws over the last few years rose to a 50% denial rate of Venezuelan asylum applicants and a 35% increase since last year in the deportation of Venezuelan immigrants. The more and more I spoke with Venezuelans on the ground in Doral, whether they were recently immigrated student protestors like Juan or heavyweight political pundits who negotiated with Trump himself, it became clear that they were entranced by a powerfully crafted political hoax. On one hand, there is Trump and Pence, who have both appeared in Doral themselves, signaling that Venezuelans are the shining diamond amongst the rough. They stand to win if they pursue the American dream, unlike their brothers and sisters from Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, and countless other Central American countries. On the other, the administration limits the likelihood of legal status through the only possible option of asylum, dooming more and more Venezuelans like Juan to the restrictive and increasingly dangerous reality of living without papers. In this way, Trump and Pence gain a crucial group of supporters in a swing state quickly tipping blue.

The majority of Venezuelans I spoke to, however, didn’t spend their times thinking of intricate political manipulations by the Trump administration. For people like José Antonio Colinas, prominent hardline activist and head of VEPPEX (Venezolanos Perseguidos Politicos en el Exilio), only one thing occupied their minds: going back home. For José, that manifested in every area of his life. He owns a business that deals in exporting and importing but almost all of José’s emotional energy is channeled into his work with VEPPEX, where he leads an organization that routinely holds informational panels, lobbies U.S. government officials, and engages in grassroots, community wide “call outs” of enchufados (wealthy Venezuelan immigrants who are living large off money made from or in relation to the Maduro government). I interviewed José three times and every time I spoke with him, I was struck by his dogged dedication to returning to Venezuela. In one interview, he described to me feeling like his life had been “stopped in time” since he fled and telling me that he had his two suitcases already packed and prepped so nothing could slow him down when the time came to return.

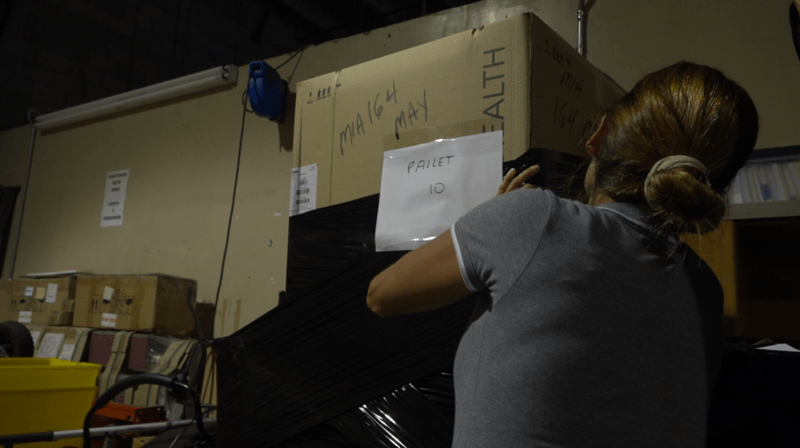

What touched me most in José was the deep well of pain and longing that lives, in some way or another, in every member of the Venezuelan diaspora. He expressed it in gruff protestations and a persistent preparation for what he was sure was to come. My mother expressed it in clouded tears held back while reminiscing with my grandfather on the home they knew would never be the same again. Even in me, that loss and longing lived, felt in the friction between the grounded, hateful underbelly of my long-time home country (the United States) and the lofty, smiling tales my mother told of a land far gone. Partly in spite of this trauma, and partly because of it, Venezuelans in Doral have created a sprawling, vibrant, and ever-growing community, full of little tokens of the lives they used to have. As I tried to fully entrench myself in the diaspora, I went to countless bustling arepa restaurants, attended forums full of helpful community voices reassuring those newly arrived, and observed the incredible scores of women dedicating their time and money to founding and running organizations like Ayuda Humanitaria Para Venezuela (run by the selfless Marisol Dieguez) and Lejos Pero No Ausentes. In every aspect of life in Doral, Venezuelans were present, building centers for gathering, grief, and political action.

One afternoon in early June, only a few days before I had to leave Doral, I got lost in Hialeah, Florida. Hialeah, unlike Doral, is a heavily Cuban community and as I drove around, trying to find my bearings, I was struck by the similarities of the two diasporas. There are scores of differences, of course, between Cubans in Miami and Venezuelans: time spent there, makeup of immigration waves, details of their respective dictatorships. But the way Cubans had managed to turn their heartbreak, their loss of a homeland, into a new one, at that moment, echoed the efforts of the Venezuelans in Doral who were day by day, carving out their own little slice of Caracas (or Maracaibo, or Merida, or wherever it might be). After a few wrong turns, I finally found myself back onto NW 74th St, in the direction of Doral. Flanked by the familiar flashes of red, blue, yellow, and the smattering of stars that make up the Venezuelan flag, I thought of the possibility of resilience and I had seen in the diaspora over the past five weeks. There was so much to do, both in American politics and certainly back in Venezuela. But during that twenty-minute drive, it was enough to just sit, take in the palm trees, and let the landscape melt into a hybrid land. Not quite Venezuela, not quite United States, but something joyful and persistent nonetheless.

More Student Views

Blossoming Bonds: Beauty and Belonging in Mexico

When I heard the news about my upcoming trip to Mexico, a surge of excitement coursed through me, and I immediately felt the urge to share this exhilarating news with my close friends and family.

Weapons of Mass Construction: Building a Puerto Rico for the People

I zip up my raincoat and turn on my headlamp as we tread along a damp trail in El Yunque National Rainforest, Puerto Rico.

Climbing the Tepozteco: Meditations on Mexico

English + Español

With sweat trickling down my forehead, I meditated on the question: What does motivation look like?