Fluvial Poetics in the Amazon

Displacement, Infrastructure, Modernization

We were in the hands of the river.

I had been told that the boat for Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, would depart from Santarém at noon. Instead, we set sail at 2 pm. The arrival was even more difficult to determine. The guy who sold me the tickets assured me that the boat would arrive at Manaus on Wednesday morning (we left on a Monday) but Caroline, who lived in Manaus—and whom I met on the boat—, explained that it was simply impossible to predict the arrival time: it could very well be Wednesday morning, but also in the afternoon, in the evening, or maybe on Thursday. I had not considered the possibility of such a long delay. My admittedly unadventurous travel agenda was suddenly imperiled.

Caroline also told me about other effects of that displacement that I was experiencing for the first time and which I could not fully understand: “You know, when we arrive in our destination the feeling is really weird, it is as if you were still moving in this same ‘boat rhythm’ while walking, as if a very particular rhythm stayed in your body.”

In this 2015 trip, my first one to the Amazon in which I took most of the photographs that accompany this essay, I learned that the forms and times of displacement in Amazonia can greatly differ from the most common ones in places we consider modern. That’s especially so when they have to do with the rivers, as still today a huge part of all travel in the region takes place through its immense waterways. So, how to tell the stories of rivers? And how to listen to the stories that rivers tell? How to narrate the displacement typical of fluvial cultures and regions? The aquatic imaginary is an essential part of Amazonian peoples, but it has also intrigued intellectuals, travelers and statemen who have written about the region, trying to understand and/or transform it. These are some of the questions that traverse my current research project on the Amazon, which might end up becoming a book with this essay’s title.

Hammocks on a boat trip on the Amazon River. Photo by Javier Uriarte / Hamacas paraguayas en un barco por el río Amazonas. Foto por Javier Uriarte

Rivers have been central in the cultural dynamics of the Amazon region, as Brazilian writer Leandro Tocantins so astutely observes in his 1952 book O rio comanda a vida: uma interpretação da Amazônia (The River Governs Life: An Interpretation of Amazonia). They have played a pivotal role in shaping the ways in which indigenous societies have found food, traveled, traded, engaged in war, celebrated rites and established various kind of exchanges with each other. At the same time, they have also molded the daily lives of ribeirinhos (people of mixed race living close to the rivers) who constitute the great majority of the region’s population. For example, throughout the Amazon basin, different communities have believed—and still do today—in the existence of underwater beings, cities, worlds (my friend Caroline also mentioned that her father would tell her stories about the “monsters” and worlds existing in the depth of the rivers) that play different roles in everyday lives.

Candace Slater’s Dance of the Dolphin studies—among other folk elements—the sexual connotations of the centuries-old popular tales of an important riverine creature: the pink dolphin (o boto rosa in Portuguese, bufeo in Spanish). Slater, a Brazilian specialist who is a professor at the University of California Berkeley, describes these beings thus: “Dolphins in the Amazon are often encantados, supernatural entities in the guise of aquatic animals who turn into men and women in order to carry off the objects of their desire to an underwater city or Encante, from which few ever return” (4). Slater gathers stories through interviews with several inhabitants of the Brazilian Amazon, exploring the various forms and connotations that these beings adopt in the region’s popular culture. This metamorphic quality is perhaps these beings’ most interesting one as it has to do with a certain protean element strongly present in the fluvial imaginary and which I particularly seek to explore. As suggested, also stories of indigenous communities often reveal a fluid and constant preoccupation with a sense of merger between humans and non-humans.

But not only native Amazonians have had an intimate relationship with the rhythms of the rivers, with the forms of understanding spaces and times typical of riverine life. These “fluvial poetics,” and their role in the everyday lives of the region’s inhabitants, have also been central to the state’s modernization and infrastructure projects of production and exploitation of the soil, as they tried to impose new ways of conceiving of travel (and, in more general terms, displacement) and have sought to “read” rivers in new ways. I am interested, then, in studying the presence, roles and connotations of rivers in the writings of various intellectuals during the first decades of the 20th century. I will compare their perspectives with those present in the indigenous stories (mostly from the Taulipang and Arekuna peoples) collected, during roughly the same years, by the German anthropologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg (1872-1924), and published in his work From Roraima to the Orinoco (1917).

Therefore, I pay special attention to the moments when rivers—their rhythms, their logic—adopt a central importance in these writings. The body of work includes a variety of texts, from novels to travelogues, from private diaries to essays, from official reports to short stories. This comparative approach will show not only when and how the different works were intensely citing each other, but also that they shared obsessions and views related to the Amazon as a modern frontier and to its role in various ways of understanding the state, nature and the dynamics between the local and the global. As I analyze an heterogenous corpus, I question some of the frequent assumptions about the Amazon, namely its deserted, “wild” or abandoned character, by bringing to the foreground the strong network of incessant and productive intellectual, material and cultural contacts that characterize it.

Igarapé near Alter do Chão, on the Tapajós River. Photo by Javier Uriarte / Igarapé cerca de Alter do Chão, en el río Tapajós. Foto por Javier Uriarte

The works studied were published between 1907-1917, during the most intense—and final—years of the period known as the rubber boom. Once Charles Goodyear achieved the vulcanization of rubber in 1839, making it suitable later on for automobile production, the Amazon turned into a cosmopolitan frontier and the world’s main producer of rubber. This export economy produced a new commercial and demographic growth in the region, transforming it into an economic center for various countries.

Some cities in Amazonia such as Manaus, Belém or Iquitos underwent significant architectural and social transformations. However, in some parts of the Amazon, this boom—a savage exploitation of the region’s natural resources—was experienced more tragically than in others. For example, notably in the Putumayo region, close to the border between Colombia, Peru, and Brazil, this boom brought devastating consequences for several indigenous communities, which suffered systematic enslavement and torture at the hands of rubber impresarios and their overseers.

This unprecedented penetration of global capital in the region transformed the uses and connotations of several waterways as they became the key arteries for commerce and for the displacement of workforce and merchandise. This new strong logic associated with water complicated the ways in which concurrent narratives of rivers played out in the region. I am interested, then, in exploring the intersections and borrowings between these diverse fluvial poetics, as well as their connections with the changing economic and social reality of Amazonia during the first years of the last century.

Some of the intellectuals I study, such as the Brazilians Euclides da Cunha and Alberto Rangel (authors of À margem da história [At the Margins of History, 1909] and Inferno verde [Green Hell, 1908] respectively) or the Colombian Miguel Triana (author of Por el Sur de Colombia [Through Southern Colombia, 1907]), were engineers working for the state who imagined the Amazon as transformed by infrastructure projects such as roads, bridges or railways. Still today, this kind of projects, like the recently finished Belo Monte dam, continue to dramatically impact the Amazon’s environment as well as its cultural, economic and social dynamics. These projects—sometimes almost fantastic in their grandiosity—have been present in the state and lettered imaginaries about settling the region for more than a century and they have involved a rethinking of the uses and rhythms of waterways.

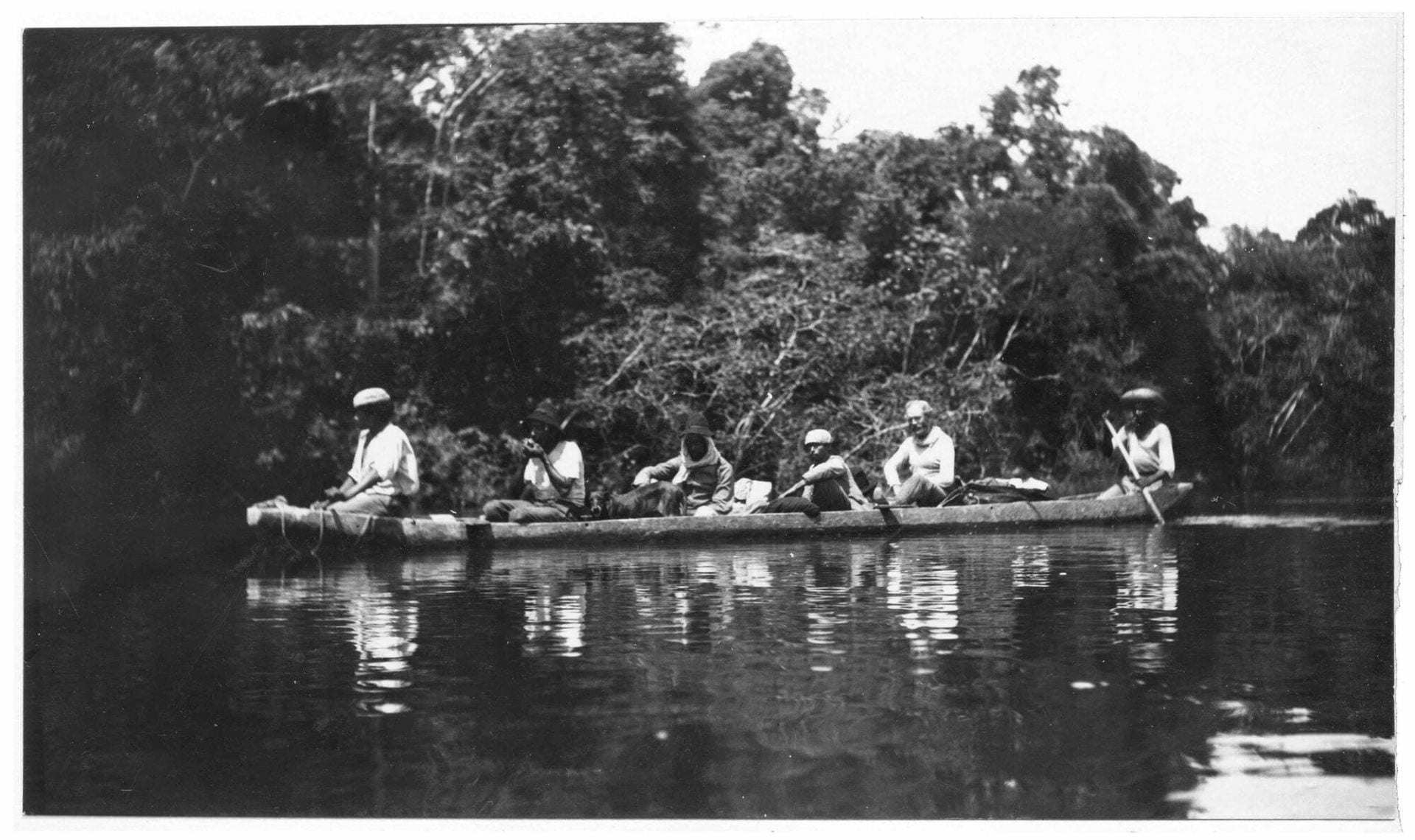

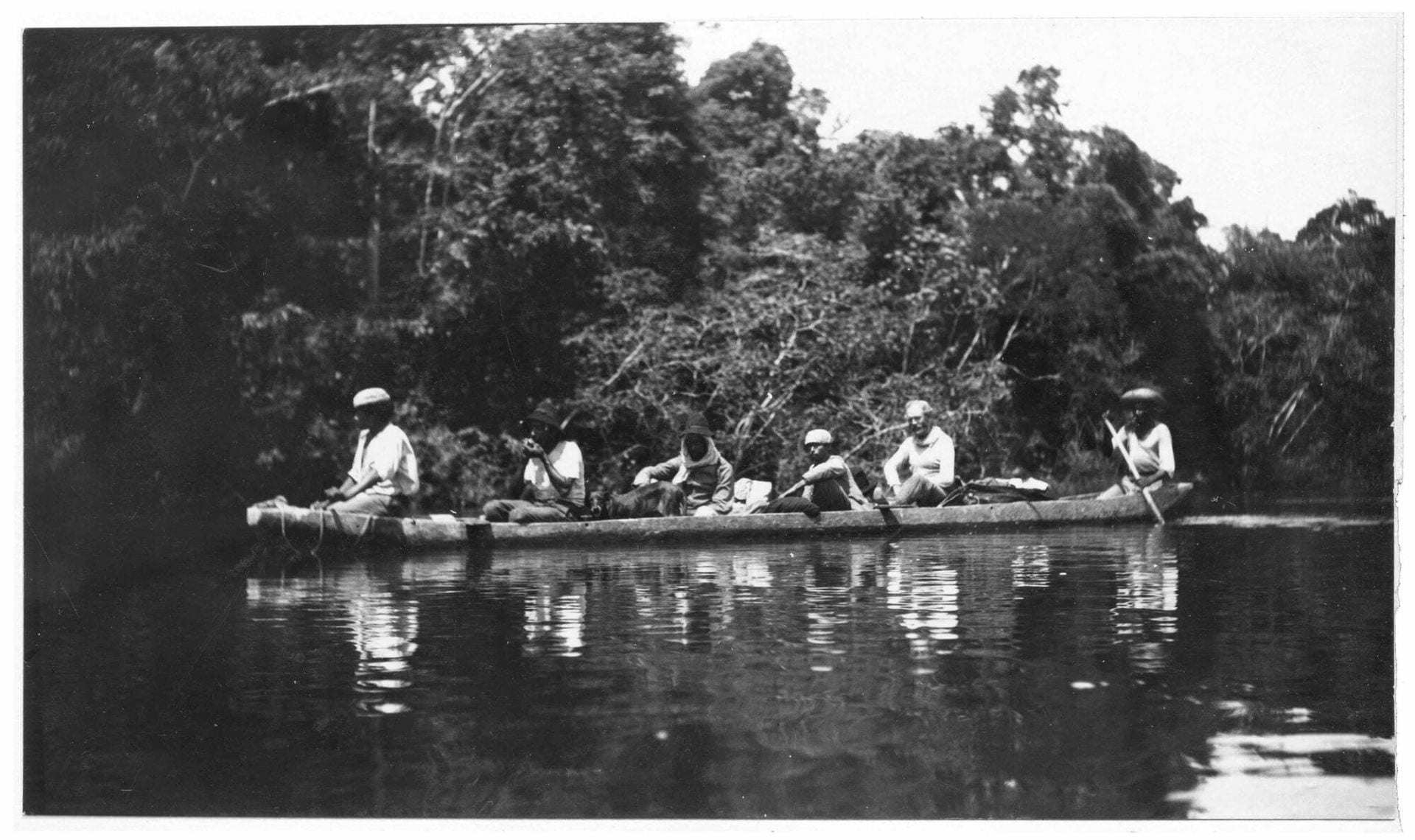

Canoe on Rio Roosevelt, Mato Grosso, Brazil Image # 218634p. Photo courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library / Canoa por el río Roosevelt, Mato Grosso, Brasil. Foto cortesía de American Museum of Natural History Library

In more general terms, infrastructure projects have profound environmental consequences, offering us interesting perspectives for rethinking the relationships between humans and the non-human world. Looking at these elements from the perspective of infrastructure, reading the “language” of infrastructure, the traces that humans leave on it, can help us understand in a new light issues of modernization and exclusion; of environmental policies and crises; of landscape conceptualization and transformation; and of labor, working conditions, and uneven development.

Rangel and da Cunha, for instance, see rivers as associated with disorder, with chaos, with barbarity. In his stories, Rangel specifically links the volubility of rivers with a violent and uncontrolled sexual behavior in some men who come from outside of the Amazonian space with the intent of taking advantage of its riches (the context of the rubber boom is key to his writings), something that he represents as sexual assault on local women (incidentally, I have found that issues of gender and sexuality have a lot to do with rivers in the Amazon). Da Cunha, referring to what he sees as the nomadic character of the rivers, suggests they cannot be appropriately looked at from a civilized perspective and also expresses a profound anxiety regarding the uncontrolled and unpredictable movement of the region’s rivers, as he seeks to propose ways to control or “tame” them, to make them “readable” from the perspective of the state. In order to do this, he makes use of a rhetoric of infrastructure that imagines the construction of bridges and dams, as he considers the effects that building highways or railroads would have in communications, national security and international relations. As suggested above, this section of the book will establish a strong dialogue with the emerging field of infrastructure studies, exploring in depth the links between infrastructure and water.

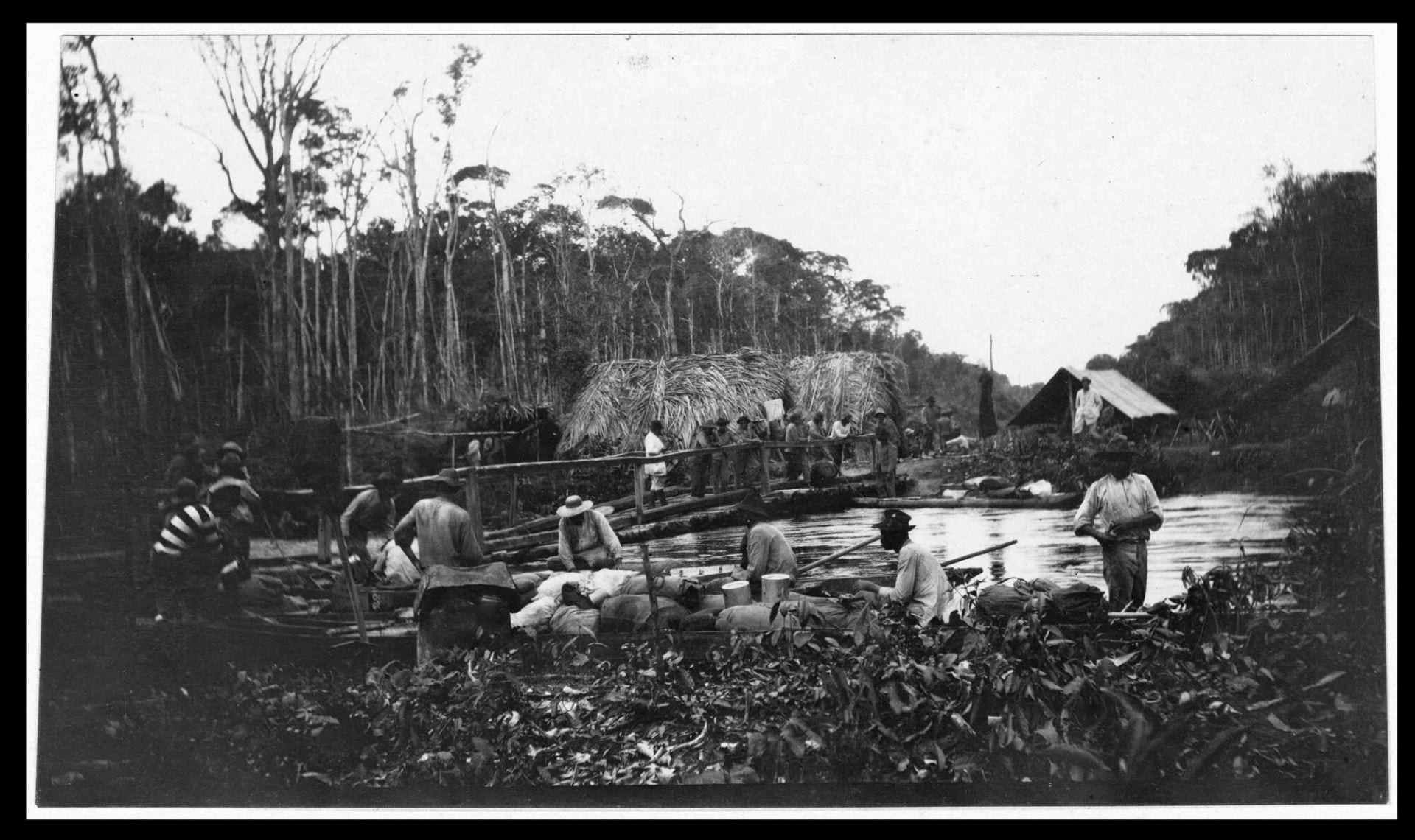

A third intriguing example has to do with Theodore Roosevelt’s trip to Amazonia, narrated in his 1914 book Through the Brazilian Wilderness, in which he sails, for the first time, a river he baptizes as “The River of Doubt” (known today as the Roosevelt River, a tributary of the Aripuanã River) because it was not on contemporary maps. It was a river whose trajectory remained unknown, as it traversed uncharted territories (from the point of view of a white man, that is). Here, “discovering” the river has to do with Roosevelt’s ideas regarding the frontier, a notion so central to the U.S. national imaginary. Once the U.S. expansion provoked the closure of the frontier, the expresident decided to take with him the hypermasculine logic of adventure (his is profoundly gendered style), akin to that of war (another important element of Roosevelt’s thinking), to the world’s largest river basin. In this trip the river becomes an obstacle to be overcome—which in turn brings to the fore the physical strength needed to perform what Roosevelt understood as a feat never achieved before. There are numerous scenes of portage, of construction of canoes, and of navigations over unknown and dangerous waters. In the many photographs included in the book, the body of the traveler (posing after hunting or while sailing) becomes an unavoidable presence.

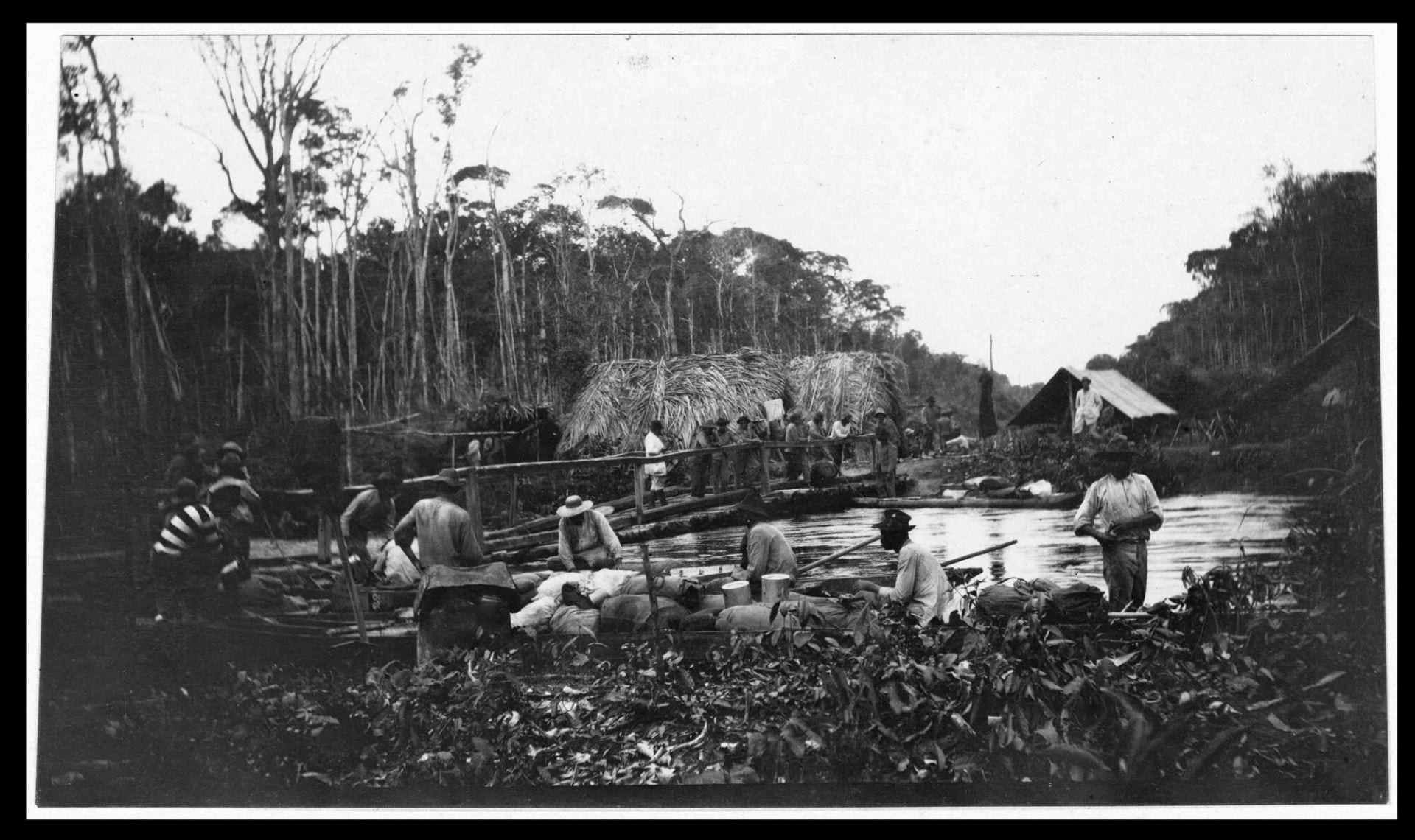

Rio Duvida camp, on Rio Roosevelt, 1913-1914 – image # 218643p. Photo courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library / Canoa por el río Roosevelt, Mato Grosso, Brasil. Foto cortesía de American Museum of Natural History Library

These different logics of domination of the waters constitute a stark contrast to the indigenous stories that show a continuity between the worlds of land, water and sky, between which the characters move seemingly without difficulties. There is also no clear distinction between humans and non-humans, as interactions between, for example, men and fish are not described as involving any relevant distance: fish talk to humans, and sometimes help them or fight against them on an equal footing. River plants and animals adopt a crucial role in various stories regarding the origin of primordial or daily elements.

Contained in these stories one can find numerous examples of all this: fish drink a special potion in order to be braver, just as natives do before war; rays were created from an aquatic plant; Pílumog, the great dragonfly, has the habit of flying above the water containers and throwing water outside of them by moving its body forward, and so in the sky the dragonfly empties a large lake; “Moto,” the earthworm, which drills the riverside sand of the sky rivers, penetrates into a rock. Also, in some occasions these stories explain that humans, falling into the river waters, are transformed into animals. Finally, just as many narratives of non-Amazonians (the example of Rangel’s stories is perhaps the clearest in my corpus), these stories about origins linked to rivers and waterways have a strongly sexualized content, and make the body—its transformations, its instincts, its fluids—one of its most visible thematic components. This bodily, sexualized or gendered element of rivers constitutes an additional aspect that I am curious about exploring.

Rio Roosevelt from hill below – Image # 315-054. Photo courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library / Río Roosevelt desde una colina. Foto cortesía de American Museum of Natural History Library

The uses and connotations of rivers have oblique and potentially productive points of contact in these quite different ways of telling aquatic stories, of conceiving of navigation, fluidity and displacement. In my trip I began to grasp the idea that the Amazon is a fragile and sometimes confusing or dissonant chorus of voices that speak through its waterways. Listening attentively to them in order to disentangle and dive into its various meanings and poetics is one of the objectives of this future book.

Poéticas fluviales en la Amazonia

Desplazamiento, infraestructura y modernización

Por Javier Uriarte

Estábamos a merced del río.

Me habían dicho que el bote saldría de Manaos, en la Amazonia brasileña, hacia Santarém al mediodía. Terminamos saliendo a las 14hs. La llegada fue todavía más difícil de prever. La persona que me vendió el boleto me aseguró que el bote llegaría a Manaos el miércoles de mañana (salimos un lunes), pero mi compañera de barco Caroline, que vivía en Manos y a quien conocí en el viaje, me explicó que era simplemente imposible saber de antemano la hora de llegada: podía muy bien ser el miércoles de mañana, pero también de tarde, de noche, o incluso el jueves. Debo admitir que no había pensado en la posibilidad de un retraso tan largo. La organización de mi viaje, que en este punto carecía de sentido de la aventura, se vio de pronto en peligro.

Caroline también me habló de otros efectos de ese desplazamiento que yo experimentaba por primera vez y que no acababa de entender: “Cuando llegamos a nuestro destino la sensación es muy rara, es como si uno se siguiera moviendo al mismo ritmo del bote al caminar, como si un ritmo muy particular permaneciera en nuestro cuerpo.”

Era 2015 y yo viajaba por primera vez a la Amazonia (las fotos de este ensayo fueron tomadas en esa ocasión). Empecé a intuir entonces que las formas y los tiempos del desplazamiento en la Amazonia pueden diferir considerablemente de los más comunes en lugares considerados modernos. Sobre todo cuando se trata de los ríos, ya que todavía hoy gran parte de los traslados en la región se dan a través del inmenso delta que la conforma. ¿Cómo entonces contar las historias de los ríos? ¿Y cómo escuchar las historias que los ríos cuentan? ¿Cómo narrar el desplazamiento típico de las culturas y las regiones fluviales? El imaginario acuático es un componente esencial de los pueblos amazónicos, aunque también ha generado interés en intelectuales, viajeros y hombres de Estado que han escrito sobre la región tratando de entenderla y/o transformarla. Son estas algunas de las preguntas que recorren mi proyecto actual de investigación sobre la Amazonia, que puede resultar en un libro con el mismo título de este ensayo.

Hammocks on a boat trip on the Amazon River. Photo by Javier Uriarte / Hamacas paraguayas en un barco por el río Amazonas. Foto por Javier Uriarte

Los ríos han sido centrales en la vida cultural de la región amazónica, como el escritor brasileño Leandro Tocantins señala con tino en su ensayo de 1952 O rio comanda a vida: uma interpretação da Amazônia (El río dirige la vida. Una interpretación de la Amazonia). Han jugado un rol fundamental en las formas en que las comunidades indígenas se han alimentado, viajado, comerciado, hecho la guerra, celebrado sus ritos y establecido entre ellas varios tipos de intercambios. Al mismo tiempo, los ríos también han moldeado la vida cotidiana de los ribeirinhos (ribereños, personas mestizas que viven cerca de las orillas), quienes constituyen la mayoría de la población de la región. Por ejemplo, a lo largo de toda la cuenca amazónica, distintas comunidades han creído—y creen todavía hoy—en la existencia de seres, ciudades, mundos subfluviales (mi amiga Caroline me mencionó también los cuentos de su padre acerca de los “monstruos” y mundos que existían bajo el agua).

El libro de Candace Slater Dance of the Dolphin estudia, entre otros elementos folklóricos, las connotaciones sexuales de los antiguos cuentos populares referidos a una importante criatura del río: el delfín rosado (o boto rosa en portugués, bufeo en español). Slater, una especialista en Brasil que es profesora en la Universidad de California en Berkeley, describe a estos seres del siguiente modo: “Los delfines en la Amazonia son con frecuencia encantados, seres sobrenaturales con forma de animales acuáticos que se transforman en hombres y mujeres con el fin de arrastrar a los objetos de su deseo hasta una ciudad submarina o Encante, de donde pocos regresan” (4). Ella recopila historias a través de entrevistas con varios habitantes de la Amazonia brasileña y explora las varias formas y connotaciones que estos seres adoptan en la cultura de la región. Esta cualidad metamórfica acaso sea la más interesante de estos seres acuáticos, ya que se relaciona con cierto elemento proteico que constituye una parte importante del imaginario fluvial y que quiero especialmente explorar. Como he sugerido, también las narrativas de comunidades indígenas incluyen una fusión entre los mundos humano y no humano, entre los cuales las transformaciones son constantes.

Pero no sólo los nativos de la Amazonia han tenido relaciones estrechas con los ritmos fluviales, con las formas de entender los espacios y los tiempos típicos de la vida ribereña. Estas “poéticas fluviales,” así como su rol en la vida diaria de los habitantes de la región, han sido también centrales en los proyectos infraestructurales y modernizadores estatales dirigidos a la producción y explotación del suelo que han intentado imponer nuevas formas de entender el viaje (y, en términos generales, el desplazamiento) al buscar “leer” los ríos de maneras nuevas. Me interesa entonces estudiar la presencia, los roles y las connotaciones de los ríos en los escritos de varios intelectuales durante las primeras décadas del siglo XX, comparándolos con las historias indígenas (sobre todo de los pueblos Taulipang y Arekuna) recogidas, aproximadamente en los mismos años, por el antropólogo alemán Theodor Koch-Grünberg (1872-1924) en su libro de 1917 Del Roraima al Orinoco.

Igarapé near Alter do Chão, on the Tapajós River. Photo by Javier Uriarte / Igarapé cerca de Alter do Chão, en el río Tapajós. Foto por Javier Uriarte

Así, presto particular atención a los momentos en que los ríos—sus ritmos, sus lógicas—adoptan mayor visibilidad en estas escrituras. El corpus con que trabajo incluye una variedad de textos, desde novelas a libros de viajes, desde diarios privados a ensayos, desde informes oficiales a cuentos. Esta perspectiva comparada contribuirá a mostrar no solo cuándo y cómo estas diferentes obras se citan intensamente unas a otras, sino que ellas comparten obsesiones y perspectivas sobre la Amazonia como una frontera moderna y sobre su lugar en formas de entender el Estado, la naturaleza y las relaciones entre lo local y lo global. Al analizar un corpus heterogéneo, cuestiono algunos de los lugares comunes sobre la Amazonia, como su carácter de espacio abandonado, desierto o “salvaje” haciendo visible una intensa y productiva red de contactos intelectuales, materiales y culturales que constituye uno de los rasgos principales de la región.

Las obras estudiadas se publicaron entre 1907 y 1917, los años más activos—y finales—del período conocido como el boom del caucho. Luego de que Charles Goodyear consiguiera la vulcanización del caucho en 1839, volviéndolo después más adecuado para la producción de automóviles, la Amazonia se volvió una frontera cosmopolita y el principal productor mundial de caucho. Esta nueva economía de exportación produjo un nuevo crecimiento comercial y demográfico en la región, volviéndola el núcleo económico de varios países.

Algunas ciudades de la Amazonia, como Manaos, Belém o Iquitos, sufrieron transformaciones urbanísticas y sociales significativas. Pero también, en algunas partes de la enorme cuenca con más intensidad que en otras (principalmente en la región del Putumayo, cerca de la triple frontera entre Colombia, Perú y Brasil), esta explotación salvaje de los recursos naturales produjo consecuencias devastadoras para algunas comunidades indígenas que sufrieron torturas y esclavitud sistemáticas a manos de los empresarios del caucho y sus capataces. Esta penetración sin precedentes del capital global en la región transformó los usos y los significados de varios ríos que se volvieron las arterias clave para el comercio y el desplazamiento de trabajadores y mercancía. Esta nueva lógica asociada al agua hizo más complejas las formas en que las narrativas paralelas sobre los ríos se fueron desarrollando en la región. Me interesa entonces explorar las intersecciones y préstamos entre estas distintas poéticas fluviales en los primeros años del siglo pasado.

Canoe on Rio Roosevelt, Mato Grosso, Brazil Image # 218634p. Photo courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library / Canoa por el río Roosevelt, Mato Grosso, Brasil. Foto cortesía de American Museum of Natural History Library

Algunos de los intelectuales que estudio, como los brasileños Euclides da Cunha y Alberto Rangel (autores de À margem da história [Al margen de la historia, 1909] y Inferno verde [Infierno verde, 1908] respectivamente) o el colombiano Miguel Triana (autor de Por el sur de Colombia, 1907) eran ingenieros que trabajaban para el Estado e imaginaron la transformación de la Amazonia como resultado de proyectos infraestructurales como la construcción de carreteras, puentes o ferrovías. Gigantescos proyectos de este tipo, como la recientemente terminada represa de Belo Monte, siguen hoy transformando dramáticamente la región, su medio ambiente y sus dinámicas culturales, económicas y sociales. Estos proyectos—con frecuencia de una grandiosidad casi fantástica—han caracterizado los imaginarios estatales y letrados relacionados con formas de apropiar la región y han implicado una reconsideración de los usos y ritmos de sus ríos.

En términos generales, los proyectos infraestructurales tienen importantes consecuencias medioambientales al tiempo que nos ofrecen perspectivas interesantes para repensar las relaciones entre los humanos y el mundo no-humano. Mirar la naturaleza y a las personas desde la perspectiva de la infraestructura, leer su “lenguaje”, las huellas que los humanos dejan en ella nos puede ayudar a entender de maneras nuevas cuestiones de modernización y exclusión, de políticas y crisis medioambientales, de trabajo, y desarrollo desigual, así como cuestiones que tienen que ver con formas de conceptualizar y transformar el paisaje.

Rangel y da Cunha, por ejemplo, asocian los ríos con el desorden, el caos y la barbarie. Rangel, específicamente, vincula en sus cuentos la volubilidad de los ríos con el comportamiento sexual descontrolado y violento de algunos hombres que provienen de fuera de la Amazonia e intentan aprovecharse de sus riquezas (el contexto del boom del caucho es central en sus narraciones). Esto aparece representado como una violencia sexual, recurrente en sus textos, contra las mujeres locales. Da Cunha, describiendo lo que ve como un comportamiento nómade de los ríos—los cuales según él no pueden mirarse adecuadamente desde un punto de vista letrado—también expresa una profunda inquietud respecto del movimiento descontrolado e impredecible de los ríos en la región mientras propone formas de controlarlos y “domesticarlos”, de hacerlos “legibles” desde la perspectiva del Estado. Para conseguir esto emplea una retórica de la infraestructura que imagina la construcción de puentes y represas al tiempo que considera los efectos que la construcción de caminos o vías férreas tendrían en las comunicaciones, la seguridad nacional y las relaciones internacionales. Como sugerí arriba, esta sección del libro establecerá un diálogo estrecho con el campo emergente de los estudios infraestructurales, centrándose en la relación entre infraestructura y agua.

Rio Duvida camp, on Rio Roosevelt, 1913-1914 – image # 218643p. Photo courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library / Canoa por el río Roosevelt, Mato Grosso, Brasil. Foto cortesía de American Museum of Natural History Library

Un curioso tercer ejemplo lo constituye el viaje de Theodore Roosevelt a la Amazonia, narrado en su libro de 1914 Through the Brazilian Wilderness (A través del desierto brasileño), donde el autor navega por primera vez un afluente del río Aripuanã. Dicho afluente era conocido por entonces como “Río de la duda” (después de este viaje será bautizado como Río Roosevelt) ya que no figuraba en los mapas. Se trataba de un río de trayectoria desconocida que atravesaba territorios inexplorados (desde el punto de vista del hombre blanco, claro está). Aquí, el “descubrimiento” del río debe leerse en el contexto de las ideas de Roosevelt sobre la frontera, noción central al imaginario nacional estadounidense. Cuando ya la expansión en este país había conquistado la frontera, el expresidente decidió llevar su lógica hipermasculina de la aventura, similar a una lógica guerrera (otra presencia importante en su pensamiento) a la mayor cuenca del mundo. En este viaje el río se vuelve un obstáculo a ser superado, lo cual a su vez coloca en primer plano la fuerza física necesaria para realizar lo que era para Roosevelt una proeza nunca conseguida. Hay por ejemplo numerosas escenas de transporte de carga, de construcción de canoas y de navegación por aguas desconocidas y peligrosas. En varias fotografías incluidas en el libro el cuerpo del viajero (en pose luego de haber cazado o navegando) se vuelve una presencia inevitable.

Estas diferentes lógicas de dominación de las aguas constituyen un fuerte contraste con las historias indígenas que muestran una continuidad entre los mundos del agua, de los cielos y de la tierra, entre los cuales los personajes se mueven sin aparentes dificultades. No hay tampoco una distinción clara entre humanos y no humanos, dado que las interacciones entre—por ejemplo—hombres y peces se describen como carentes de toda distancia relevante: los peces les hablan a las personas y a veces las ayudan o luchan contra ellas de igual a igual. Las plantas y animales de los ríos adoptan papeles cruciales en varias historias sobre el origen de elementos primordiales o vinculados con la vida diaria.

En estas historias se puede encontrar numerosos ejemplos: los peces toman una poción especial para ser más valientes, del mismo modo que los indígenas antes del combate; las rayas se crearon de una planta acuática; Pílumog, la gran libélula, tiene el hábito de volar sobre los recipientes de agua y lanzar esta afuera echando su cuerpo hacia adelante, y así es que vacía un gran lago en el cielo; “Moto,” la lombriz de tierra, que taladra la arena de las riberas de los ríos, se introduce en una roca. Además, estas historias a veces cuentan que los humanos, al caerse en los ríos, se transforman en animales. Finalmente, del mismo modo que muchas narrativas de personas ajenas a la Amazonia (el caso de los cuentos de Rangel acaso sea el más claro en mi corpus), estas historias sobre orígenes vinculados a los ríos tienen un contenido fuertemente sexual y hacen del cuerpo—de sus transformaciones, sus instintos, sus fluidos—uno de sus componentes más visibles. Este elemento corporal vinculado a los ríos constituye un aspecto más que procuro explorar.

Rio Roosevelt from hill below – Image # 315-054. Photo courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library / Río Roosevelt desde una colina. Foto cortesía de American Museum of Natural History Library

Los usos y los significados de los ríos tienen puntos de contacto oblicuos aunque potencialmente productivos en estas formas tan distintas de contar historias acuáticas, de concebir la navegación, lo fluido y el desplazamiento. En mi viaje empecé a intuir la idea de que la Amazonia es un frágil coro de confusas o disonantes voces que hablan a través de sus caudalosos ríos. Aprender a escuchar con atención para encontrar sentidos y poéticas—y sumergirme en ellos—es uno de los objetivos del libro que imagino.

Spring/Summer 2020, Volume XIX, Number 3

Javier Uriarte is Associate Professor in the Department of Hispanic Languages and Literature at Stony Brook University. He is the author of The Desertmakers: Travel, War, and the State in Latin America (Routledge 2020), and co-editor (together with Felipe Martínez-Pinzón) of Intimate Frontiers: A Literary Geography of the Amazon (Liverpool U. Press, 2019).

Javier Uriarte es Profesor Asociado en el Departamento de lenguas y literaturas hispánicas de Stony Brook University. Es autor de The Desertmakers: Travel, War, and the State in Latin America (Routledge 2020), y co-editor (junto con Felipe Martínez-Pinzón) de Intimate Frontiers: A Literary Geography of the Amazon (Liverpool U. Press, 2019).

Related Articles

Borderland Battles

When then-President Juan Manuel Santos signed a peace accord with one of the Western Hemisphere’s oldest guerrillas in 2016 (the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), optimism ran high that an end to decades-long violence in Colombia had been…

Exile Music

Novels about the Holocaust and Jewish survival span countries and languages and audiences of all ages. Such stories tend to be told against a European or United States background. Rarely does a novel involve European Jewish refugees who found sanctuary in Latin…

A Seat at the Table

About a year ago, a foreign visitor to Harvard gifted me with an odd realization. It doesn’t seem as something intentionally taught, but it may have been—it is impossible to know someone else’s intentions. What I know is that his spatial and cosmological imagination grew…