Fried Rice and Plátanos

In November 1968, two food critics for New York magazine enthusiastically announced the arrival of a new cuisine in town: “Probably the only benefit that has been derived from the U.S.-Cuba estrangement is the establishment of the Cuban-Chinese restaurant as part of New York’s gastronomic life.” Chinese Cuban restaurants emerged in Manhattan from Chelsea to the Upper West Side. At Asia Pearl on 54th Street, Spanish-speaking customers filled the plain formica tables or sat at the counter for their fried rice and traditional Cuban dishes. The reviewers noted: “The fried rice dishes are good and seem to be comfortably placed between the Chinese and Cuban cooking. Pork, ham, shrimp and one called simply special are $1.05 each. It is the Cuban side of the menu that should be the most novel for the average New Yorker. The scope of the familiar omelet is enlarged by the addition of either banana, shrimp or Spanish sausage (from 85 to 95 cents).”

La Fortuna, a former Chinese restaurant in Sagua la Grande, which had a large Chinese presence and was the birthplace of artist Wifredo Lam.

While this Chino Latino cuisine may have surprised the magazine’s readers, it was perfectly comprehensible for the influx of Cuban immigrants arrived since the 1959 Cuban revolution. They would have been familiar with Havana’s Barrio Chino, which by mid-century was one of the largest Chinatowns in the Americas, or encountered Chinese-owned restaurants and shops in provincial towns across the island. Indeed, the Chinese Cuban eateries in New York and elsewhere are one strand of a history of global migration circuits between Asia and the Americas.

From 1847 to 1874, about 125,000 men from southeastern Guangdong Province arrived in Cuba as indentured laborers for sugar plantations, railroads and mining prior to and during the period of gradual abolition of slavery. The coolie trade ended after an investigative commission exposed its atrocities in 1874. Those who remained settled in Cuba as agricultural and urban workers, artisans, labor contractors and market gardeners or remigrated elsewhere. As early as the 1860s they established eateries and food stands in an emergent Chinese district of Havana, and within a few decades merchants from Hong Kong and San Francisco set up transnational firms for the import of food products and luxury goods from China.

Food is a central motif in narratives about the Chinese role in the Cuban ajiaco (stew), a metaphor for the multiple ethnic components of Cuban national identity. The Chinese who participated in Cuba’s independence struggles beginning in 1868 and made interracial marriages and other alliances were key to a process of integration. War narratives emphasize the Chinese role in patriotic and noncombat auxiliary activities, such as delivering messages, preparing food and acquiring medicine and clothing for the rebels. In 1884, for example, a group of Chinese charcoal makers protected hungry Cuban insurgents from Key West from Spanish forces. Once they were out of danger, the Chinese welcomed the troops with coffee, as any good Cuban would do. The Cuban commander commented that “they prepared a magnificent meal: rice with chicken, fried pork, plantain and sweet potato: a Creole meal” (Antonio Chuffat Latour, Apunte histórico de los Chinos en Cuba,[1927]. As Shannon Dawdy notes in her article on food, farming and national identity in Cuba, the foundations of an emerging national cuisine were viandas or starchy roots and tubers such as sweet potatoes, yams and manioc, as well as plantains, which were native-grown and produced on small-scale farming plots. (New West Indian Guide 2002) A Cuban nationalist movement similarly developed in opposition to both foreign control and large-scale agricultural regimes. Although the Chinese were recent arrivals, through their preparation of a quintessential Cuban meal they were represented as supporters of Cuban independence and potential citizens in the new republic. These kinds of narratives undermined the more common racialized descriptions of the Chinese as a “yellow peril” that circulated throughout the Americas since the 19th century.

- Typical meal at La Caridad 78 Restaurant on Broadway in New York City.

Chinese immigration to Cuba was officially restricted under the U.S. occupation in 1899 and into the republican era, but the ban on Chinese laborers was lifted to boost sugar production during World War I. With an influx of new immigrants, bustling Chinese communities took shape in Havana and other provincial towns. Restaurants, bodegas, laundries, shoe and watch repair shops, bakeries, photography studios and pharmacies, as well as cultural institutions such as ethnic associations and theaters, lined the streets of Havana’s Barrio Chino.

Everyday interactions and intimacies, many of them around food and restaurants, fostered an environment in which the Chinese became Cuban. They made ice cream with fresh tropical fruit, sold savory fried snacks on street corners and ran restaurants that served working-class Cubans. Truck gardeners provided fresh cabbage, lettuce, tomatoes, carrots and beets to the Cuban population. Chinese vendors delivered produce and fish door to door in provincial neighborhoods. Cuban women who married Chinese men often learned to cook Chinese dishes and participated with their mixed-race children in religious and community life.

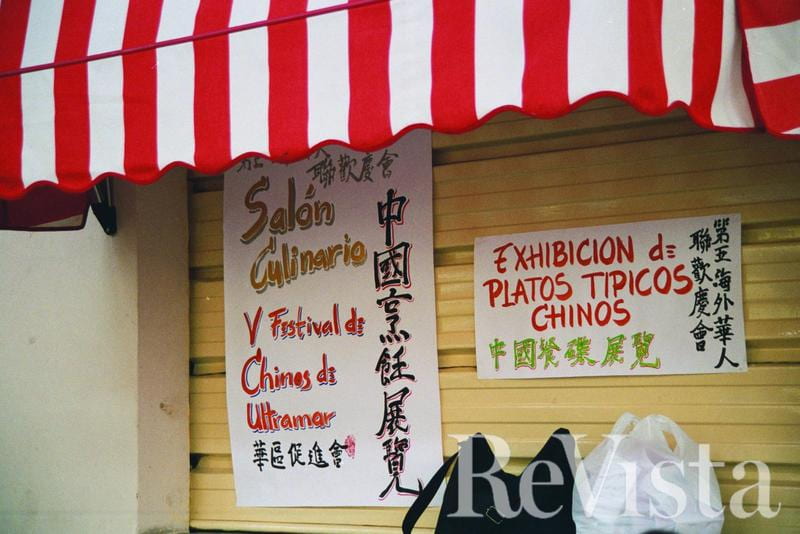

Culinary exhibit of typical Chinese dishes at Fifth Festival of Chinese Overseas, Barrio Chino, Havana. (2003).

In an October 2015 blog, journalist Tania Quintero Antúnez recalls carrying a metal container for take-out dinners from a Chinese restaurant just two blocks from her house in her Havana neighborhood. In the 1950s, 15 centavos could buy a “complete” meal of meat, rice and beans and plátanos maduros. Her family also frequented La Estrella de Oro on Monte Street for fried rice, chop suey and maripositas chinas (fried wontons). (https://www.martinoticias.com/a/salimos-a-comer-algo/105764.html ) The award-winning composer, conductor and arts educator Tania León fondly remembers her Chinese grandfather, born in Cuba to two Chinese parents. He presented León with her first piano when she was five years old. She accompanied him to dragon parades that coiled through Zanja Street during the Chinese New Year and to dinners at the famous restaurant El Pacífico. In a personal communication in 2005, she recalled: “We would have dinners there with his friends (owners and employees of the restaurant) and return home late.”

After the revolution, the final stage of the nationalization of private commerce in Cuba in 1968 produced an exodus of middle-class entrepreneurs, among them Chinese immigrants. They settled in Cuban neighborhoods of Little Havana in Miami, along the west side of Manhattan, and across the Hudson River in Union City, New Jersey, where they established small businesses. Now, fifty years later, we see the fading imprint of these later migrations upon urban landscapes.

Chinese Cuban restaurants offer a utilitarian ambiance, simple paper placements adorned with a map of Cuba and ample portions for their mostly working-class patrons. Mi Chinita (later Sam Chinita) on the corner of Eighth Avenue and 19th Street was known for its chrome, railcar-inspired façade typical of New York City diners of the era as well as for its ropa vieja (shredded beef in tomato sauce) and fried rice. At La Caridad 78 on Broadway, the menu’s “special combination platters” consist of arroz frito especial with ham, roast pork and shrimp alongside standards such as plátanos maduros, chicharrones de pollo (fried chicken chunks) or costilla ahumada (barbecue ribs).

Above all, Chinese Cuban restaurants provide for their Cuban customers a touch of nostalgia for a prerevolutionary era. Lisandro Pérez, CUNY professor and expert on the Cuban presence in the United States, was 11 when he left Cuba. He recalls frequenting El Wakamba in downtown Miami for fried rice and plátanos maduros. In his Cuban New Yorker blog, Pérez describes the interior of La Caridad 78 during a 2012 outing: “The décor (if we can call it that) is punctuated by yellowed magazine and newspaper reviews of the restaurant, and presiding over all of it is a framed image of La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, the restaurant’s namesake and the island’s Catholic patron saint, who looks over the restaurant’s tables with their Chinese zodiac paper placemats.” (https://cubannewyorker.wordpress.com/tag/la-caridad-78/)

Today only a handful of the original Chinese Cuban restaurants that proliferated along Eighth Avenue and in the boroughs remain, due to high rents, gentrification and an aging immigrant generation. Kenny Yu’s grandfather had established a laundry business in Cuba in the 1920s, but fled the island after the revolution and opened a restaurant in Chelsea in 1970. Yu did not meet him until the age of 12, when his grandfather brought family members directly from China to the United States. Since high school Yu worked in the restaurant, La Chinita Linda, and eventually took it over. In a June 2003 interview with Larry Tung, Yu commented that “the second and third generations are not interested in the restaurant business. They want to do other professional work, like [becoming] lawyers and doctors.” (http://www.gothamgazette.com/citizen/jun03/original_cuban_chinese.shtml)

The original Chinese Cuban restaurants have expanded their offerings to account for shifting demographics and more recent migrations from Latin America. At the remaining establishments, older Spanish-speaking Chinese staff are joined by newer Chinese immigrants, including some from Peru and elsewhere in Latin America. La Dinastia on 72nd Street now refers to its cuisine as “Chinese-Latin” and offers other Caribbean specialties such as mofongo.

As anthropologist Lok Siu notes in a 2008 Afro-Hispanic Review essay, these Chinese Cuban restaurants—and Chino Latino restaurants more broadly—claim “a distinct ethnic cuisine and cultural space within the urban landscape of New York City.” They challenge fixed notions of national culture that subsume alternate identities. Census categories and racial hierarchies fail to account for the secondary migrations of Asians from Latin America and the Caribbean to the United States. This neglect is beginning to change, as scholars, writers and artists increasingly explore the complex identity formations of Asians from Latin America and the Caribbean who re-migrate within the Americas, especially to the United States and Canada. They grapple with mixed-race identities, hybrid languages and histories of migration and displacement.

Emily Lo’s family history is rep- resentative of the twists and turns of global migration between Asia and the Americas. Lo’s Cuban grandmother married a Chinese immigrant who returned to China in 1949 and was never heard from again. Her grandmother left Cuba with her young mother in 1962 and found work as a seamstress in a New York City factory. Her grandmother’s niece, Aida, married Chinese immigrant Jesus Loo, whose family owned restaurants in Cuba. When Aida and Jesus left the island, they opened a chain of Chinese Cuban restaurants in New York, including the flagship Asia Número Uno on Eighth Avenue at 55th Street. The Loos were among several restaurant owners featured in a 1985 New York Times article by Marvine Howe that noted the gradual disappearance of these establishments. Their children grew up speaking English, Spanish and Chinese and helped out with the family business. Jesus Loo’s restaurants in New York City helped to fund the trans-Pacific migrations of his cousins, including Emily Lo’s father, a Chinese from Indonesia. In her 2007 essay “A Cuban-Chinese Familia,” Lo relates how her father met her Chinese Cuban mother in New Jersey: “He was set up with my mother when she was nineteen and he twenty-nine, and this was how my own Cuban-Chinese-American familia came to be” (Cuba: Idea of a Nation Displaced).

Some Asian Latinos such as Emily Lo have embarked on journeys to learn more about their family history. Lo laments: “I could never get stories out of Aida at our lunches at La Nueva Rampa, a Cuban-Chinese restaurant in Manhattan….We’d sit down and order rice and beans, bistec empanizado, breaded steak, and the kind of tostones my grandmother and I used to hand-make in our kitchen.” Although retired from the restaurant business, Aida Loo would easily fall into old patterns at the eatery owned by her friends: “She grabs her own silverware from the tray in the back. She finds the plastic pitcher of ice water and marches it head high to our table.” Lo describes her journey to uncover her family history and frustrations with the boundaries imposed by academic disciplines and U.S. racial categories. She explains: “I just wanted to know how I fit in my family. And I wanted to know how my family fit in a larger scope of history. We had studied immigration in school, but our textbooks never considered families like mine, families that were of blended heritage before they even set foot in America. We celebrated hyphenated ethnicities all the time in our diversity-conscious curriculums, but adding one more, like Cuban and Chinese American, didn’t fit any mold.”

Today, as descendants of Chinese Cubans in the United States make their way to Cuba in search of family history, they are met with a Barrio Chino in transition. After 1959, the population of ethnic Chinese in Cuba had sharply declined, and only about one hundred of the prerevolutionary immigrant population remains. However, the Chinese presence in Cuba has resurfaced through state investment and infrastructure projects, Chinese products such as bicycles and televisions, cohorts of Chinese students learning Spanish, and a handful of Chinese entrepreneurs. Festivals draw younger generations of mixed Chinese Cubans. The remaining Chinese ethnic associations run restaurants in their former meeting rooms to boost tourism and ensure survival. They maintain the tradition of serving Chinese food alongside comida criolla and pizza, popular among Cubans. Whether future reforms will be substantial enough to spur another influx of Chinese immigrant entrepreneurs is an open question. It is clear, though, that food and restaurants will continue to be an integral component of the Chinese Cuban migration experience in the Americas.

Fall 2018, Volume XVIII, Number 1

Kathleen López is a faculty member in the Department of Latino and Caribbean Studies and the Department of History at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. She is the author of Chinese Cubans: A Transnational History (North Carolina, 2013) and an expert on historical and cultural intersections between Asia and Latin America.

Related Articles

From Vendedor to Fashion Designer

English + Español

Korean immigrants in Latin America are shaping and developing fashion economies there. Upon arrival, Korean immigrants to Argentina and Brazil may have been lonely, isolated and confused…

Shared Sentiments Inspire New Cultural Centers

English + Español

In the early afternoon of January 3, 2018, in the mountainous village of Shicang, Zhejiang Province, China, firecrackers burst into the air and flags waved in the wind as a parade of Clan…

Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century

A Review of Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century Contemporary Human Rights and Latin America On September 5, 1921, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Hollywood’s then best-paid star, attended a party in San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel, drank...