Friends Who Disappear

Reflecting in the Time of Covid-19

I first met Marvyn Perez in 1988 when I was teaching English in Mexico. I was having dinner at the home of Guatemalan exiles, fellow instructors at the university in Puebla. Marvyn must have been 18 or 19 years old, but looked much younger. He was with his high school girlfriend from Los Angeles. Both were clad in jeans, T-shirts, and gold-rimmed glasses. Though shy, Marvyn had an easy smile that seemed hopeful and expectant. He was in Puebla to begin medical school. It wasn’t until sometime later that I learned he was a torture survivor.

Marvyn and his sisters, 1982. Courtesy of Marvyn Perez

By 1993 when we next met, I was collecting survivor testimonies as I began graduate school at Stanford University and Marvyn was a 23-year-old medical resident at the Autonomous University of Puebla. Now more confident and mature, his kind eyes were still framed by curly, black hair and gold-rimmed glasses. No doubt, his gentle demeanor reassured many a child and parent seeking medical care. Because we were friends and both had university educations, I somehow thought that there was something we shared that would make taking his testimony easier. Perhaps some point of access that would allow for a less painful, if not seamless entry and exit from his experience.

Probably, I thought that my book knowledge of Guatemala prepared me to understand his experience. Somehow, I believed that the intersection of all these shared or almost shared experiences would help Marvyn open up and talk about experiences that are, in many ways, unspeakable. Naively, I thought that together we might be able to make sense of what had happened to him. In “Vocabulary,” Chilean poet Ariel Dorfman writes:

Let me tell you something

Even if I had been there

I could not have told their story.

— Dorfman, Ariel. 1993. “Vocabulary.” In Forche, Carolyn, Ed., Against Forgetting. Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness. [New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 615-616].

The Guatemalan Truth Commission documented the forced disappearance of 50,000 people from 1960 to 1996. Marvyn was 14 when he was disappeared in Guatemala. He was one of 5,000 children selected by the army for forced disappearance. Marvyn spent that day telling me his story as the sun rolled over the valley of Puebla and set behind the snow-capped Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl volcanoes. Nearly three decades later, I am unclear if there is any sense to be made of what happened to him, but I know that it is a story that must be told. In the time of Covid-19, I find myself once again reflecting on those who have disappeared, on that long-ago suffering for which there are no words, but we must try to put into words to recognize and understand how the pain of loss shapes our present and future.

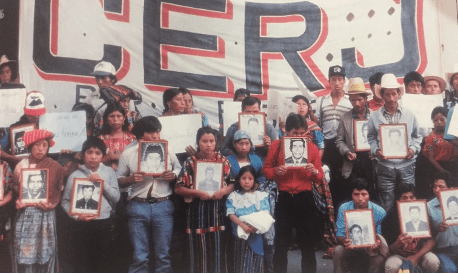

Families of the Disappeared, Santa Cruz del Quiche, 1989. Courtesy of Amilcar Mendez

We sat down in his living room on rustic, locally made furniture surrounded by the bright white walls that he had found neither time or interest to decorate on his way to bed from hospital rotations. I was grateful that he was giving up sleep to remember this painful experience with me.

Imagine you are 14 years old and among the privileged minority in your country who go to high school. You have joined a student organization protesting cuts to education and lack of access to public schools. You and your friends have made some leaflets demanding your rights to education and want to distribute them. But you live in a country where being caught with this kind of leaflet has a legal definition: “possession of subversive literature”—a punishable crime. You are a really good basketball player; on the national team, in fact. You are strong, fast and daring. You have some fire crackers – which are legal because they are made with gun powder by the same people who make army munitions. You meet up with two of your friends from school and you put the leaflets in a paper bag with some of the firecrackers. One of your friends extends the firecracker fuse with toilet paper, broken off match heads and water. You attach the paper bag of leaflets and firecrackers to the pulley you and your friends have rigged with some square knots in a piece of rope you have thrown over a lamppost on a busy street. It is exhilarating. One of your friends lights the fuse and you start to run down the street. You turn to watch the leaflets floating through the dark smoky air as you hear the crackle and boom of the firecrackers. You are awestruck at the spectacle you have made with your friends. You start to smile and just as you are about to congratulate your friends, you hear the sirens.

You and your friends run and hop on a bus, get off at the next stop and get on another bus. But the siren follows you, until the bus stops for it. The police get on the bus. They order all the passengers off and separate the men from the women. They search everyone. Then, they call you and your friends. The uniformed national police say, “We know who you are. Don’t play stupid.” They begin to beat you with the butts of their rifles as they push you into their car. As the car drives away, one of them looks at you and says, “I want to cover you with gasoline and light a match. Then, you’d talk.”

Marvyn and his friends were taken to the National Police Department of Investigations. After sitting in silence for hours, the interrogations began. Then, the children were locked in a bathroom where they slept on the floor until dawn. They were awoken by the police bringing in two other high school students, both badly beaten. Then, the police brought in a man who was tied up from head to toe. They filled the wash basin with steaming hot water. They accused the man of stealing as they slammed his face down into the sink and held him under the hot water as he choked for air. Then, the police dragged him away.

Soon after, the police returned and put a rubber hood on one of the boys. One by one, each of the children was then hooded and taken into an adjacent room. When not the hooded subject of the police interrogations, they could hear what was happening to their friends: the police punching, kicking and shouting, followed by the screams and moans of their friends. Marvyn told me he was the last to be hooded and dragged away. He was beaten and kicked. This first day was not a focused interrogation. The police brutalized the children, shouting “Confess! Confess!” with each blow.

The second day, still in the police station, the army took charge. One-by-one, the children were taken a room where they were shown photos in an album.

“Do you know him? Do you know her?” asked the uniformed officer.

“Do you know her?” an official asked as he pointed at a girl.

Marvyn knew she was a high school student who had left school to join the guerrillas in the mountains. Marvyn shook his head and said, “No.”

“Liar!” shouted the officials.

Three army men hit Marvyn, slammed his face into the table, and pulled his hair as he responded, “No” to the cascade of shouted questions. One official, whom Marvyn describes as looking like someone from Guatemala’s notorious G-2, the army’s secret police unit, had a lot of information. He looked at Marvyn, then pointed from one photo to the next, “Look,” he said, “this one belongs to the Revolutionary Student Front. This one joined the guerrilla last year. We killed this one. And this one, well we have him.”

That same day, the police captured two more students in downtown Guatemala City. There were three students, but one of them almost got away. The police shot and killed him as he fled. That same night, Marvyn’s two sisters and two other teenagers were disappeared—a defining element of forced disappearance is the elimination of the individual from the protection of the law through their disappearance. Forced Disappearance was a standard weapon of the Guatemalan government against dissent while maintaining an official posture of ignorance and government denial of the forced disappearance of the victims. Bruised and bloody from being beaten, they were all brought to the same police bathroom where Marvyn and his friends were being held. None of them were allowed to speak. The following morning, two more children were brought in. The police behaved as if they were bringing in wild game caught in a hunt.

That second morning at the police station, Marvyn and his two sisters were put in a room together with an army colonel, at least all the officials called him “Colonel.” This man was playing the “good cop,” Marvyn recounts.

“Look, kids,” he said, “it’s better if you talk. Nothing bad is going to happen to you. Don’t worry. You just have to say a few things and then you will be free.”

The colonel turned to his sister. He said, “You should talk. You are the oldest. You understand the situation. You can save the lives of your brother and sister.”

Marvyn and his sisters each told the colonel that they had nothing to say.

“Look, we understand that you do these things for patriotism, for your country, because you have big hearts” responded the colonel. “But you have been manipulated by the guerrilla. They are delinquents causing trouble in the country. It will be better if you talk.”

But Marvyn and his sisters did not talk. “We had nothing to say,” explains Marvyn.

The third day, the colonel began to interrogate the children individually. “Who is your leader?” he demanded to know. All the children began to give information, but it was all different because they were inventing it as they went along. When the army officials realized this new information was pure fabrication, they began to beat the children again.

On Tuesday, they put a capucha (hood) on Marvyn. He had heard about the capucha. He thought it was a plastic bag and that they would sit him in a chair and beat him. But this was a more sophisticated operation. The army officials put a rubber hood over his head—there were no openings for his mouth, nose or eyes. He could barely breathe. They bundle-tied his hands and feet together behind his back. They tied a cord that was connected to the hood to his hands and feet. Then these army men threw 14-year-old Marvyn face down on the floor and pulled the cord bending his back and contorting his body unnaturally upwards. They hung him in this position.

Marvyn remembers the hanging like this:

It produces a searing pain and at the same time, because of the rubber hood, you can’t breathe. Then, they begin to ask you questions. They begin to torment you and you can’t breathe. When you are asphyxiating, they drop you back down on the ground. You hit the floor hard. Then you take a breath and they pull you up again and hit you in the stomach to knock the air out of you. Then, up and down, up and down, over and over again. The punches aren’t just in the abdomen, they are everywhere. Each time when you begin to asphyxiate, they drop you to the ground. Right as you start to take a breath, they pull you up and the rubber hood asphyxiates you and the beating starts again. And all along they are shouting at me, “Talk or we’ll kill your sisters.” Even if you had something to say, you can’t talk when you are asphyxiating with a rubber hood on your head. This torture is how they begin to break your moral character, to destroy your conscience. They did the same thing to my sisters: “Talk or we will kill your little brother!”

After being tortured, the bruised and bloodied children were taken to a room where they were left wondering what would happen next. They were beginning to lose their sense of time and self. Very late that night, a group of unknown men in their 30s came into the room. These tough-looking, muscular men had very mean faces. As soon as the door closed, they sneered at the children and said, “You are from the FIL.”

“What’s the FIL?” responded the children.

“We knew the FIL were the Irregular Forces of Liberation, a structure of the EGP [Ejercito Guerrillero de los Pobres, Guerrilla Army of the Poor],” explains Marvyn. “They repeated, ‘You’re from the FIL.’ We said, ‘We don’t know anything about that.’ With contempt, they said, ‘Don’t be assholes, you sons of bitches. You know what that means. You just wait.’ And, then they left us alone again.”

A little while later, these rough men returned. “Blindfold them,” they ordered the army soldiers—most likely D-2 or G-2 Army officers—standing guard at the police station. “We are taking them with us.” Though they never identified themselves, this time they made it clear who was in charge and who they were. The teens had been captured by police, turned over to army officials and were now in the hands of a death squad—an organized group of armed men with direct ties to the army and/or police that operates under the shroud of secrecy as it terrorizes the population with disappearances, kidnappings and extrajudicial executions. The secret nature of these squads guaranteed impunity for the perpetrators as the army and police claimed ignorance of their activities. Day by day, as the children were disappeared, tortured and transferred from police to army to the death squad, government officials claimed ignorance of their whereabouts and even blamed the guerrilla for their disappearance.

Marvyn and the others realized they had moved through the official hands of the police to uniformed army officials to a secret death squad. Marvyn saw sadness, fear and dread in his sisters’ faces: “Looks that we had each reconciled ourselves with death and that the moment to die was upon us.”

All of them were crying. They tried to embrace one another, to bid farewell with a trace of kindness, even as the FBI handcuffs, which tighten on wrists with any movement, pinched ever further with each human touch.

The death squad goons pushed the children downstairs and shoved them into a car. Inside, there were four other kids, friends who had also been captured. All these children, packed one on top of the other on the floor of the car, began to whisper to one another. “Don’t talk because whoever speaks is dead,” snarled one of the adult men whose job is to torture children. The car fell silent except for the revving engine as they drove into the unknown.

Suddenly, the car screeched to a halt. “Here,” one of the goons barked, “we’ll get rid of one of them here.” As the children shook with fear, these grown men laughed and drove on. Every now and again, they would repeat this torment. Time stopped. Time sped by. The children’s bodies quaked in terror, their mouths went dry, they couldn’t swallow, they couldn’t speak, they were cold, they were hot, they were hungry, they were thirsty, they couldn’t breathe, their wrists hurt, their fingers were frozen, their hands were numb. They could feel the breathing and warmth of the child above and below, feel the soft belly, the boney elbows and knees, the near suffocation of the human pile on the floor of the speeding car.

They reached a house. They heard the gates open and close as the car drove in. Still bound and blindfolded, the children were pulled and pushed out of the car. They shivered. The night felt very cold.

Blindfolded and handcuffed, we walked up some stairs into a house. Immediately upon entering the house, life became even more gloomy and frightening. With the blindfold, it was already obscure, but entering the house, everything seemed to be consumed into darkness. The odor was horrible, a mixture of blood, urine, excrement— the screams and moans of people being tortured—a terrible thing. We knew this was what awaited us. This was perhaps the biggest blow.

For two weeks in the clandestine jail, Marvyn and the other children were tortured in every way. Marvyn was beaten, burned, slapped, choked, hung, subjected to mock execution, drowned, asphyxiated and shocked with a cattle prod on every part of his body. Marvyn and his sisters were among 32 known children (defined by the International Convention on the Rights of the Child as under 18, and whose rights are protected by that international convention) disappeared in June of 1982 and among 13 released in a large public display of the children presenting forced confessions to the press. In Marvyn’s group of 16 disappeared middle and high school students, three of his friends remain missing. The whereabout of the other missing children remains unknown. All these stories of torture that he shared with me slipped into some unconscious part of my memory behind the image of the unspeakable.

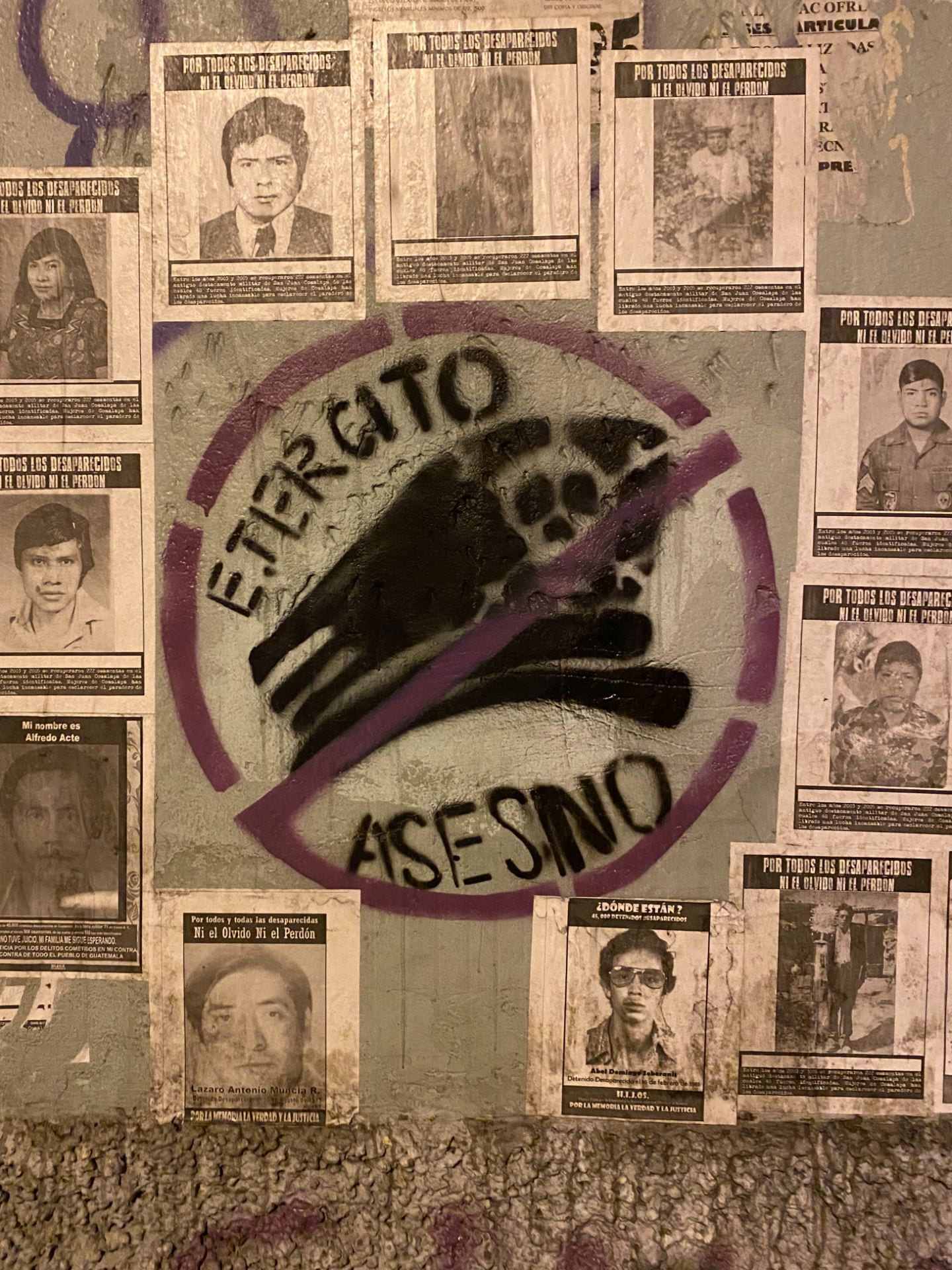

Where are the Disappeared? 2022. Courtesy of Luisa Samayoa.

Marvyn’s story, and now my story telling it, is about how traumatic experience enters your body or soul and won’t let go. How it stays with you over time. It is about how trauma occupies different spaces—spaces of memory, forgetting, and daily life. His story and mine are about pain, depression and the struggle to understand. Our stories remind us that traumatic experience shapes the contours of the present manipulating how we allow past trauma to seep in and how we hold it at bay. And yet, painful experiences seep into every bit of our lives despite all the complicated formulas we develop to separate the past from the present or work from daily life. Ultimately, this is a story about exposure to intimate traumatic memories of others and how we are all interconnected when we witness and share lived experience. This is the story of how other people’s stories can shape our lives and perhaps how collective memory is made over time. It is about repression, recovery and liberation. It is about keeping hope alive despite all experiences to the contrary. It is about what we do while we are waiting for the barbarians or living in their midst.

Marvyn and I have talked about why torture is used, what it does to the victims and to society. There seems to be a continuum of complicity from the señora who volunteers the “subversive” to the police to the barbarians who torture while shouting “Confess! Confess!” To those who seem almost proud of the knowledge they have accrued and delight in sharing it with their captives, “This one we killed.” To the deeply macabre and sinister that seek to destroy the essence of what it means to be human, to be whole. To break the moral anchor and scar the soul of a fellow human being. To strip an individual of dignity through exposure to horror. Those who miraculously survive are forever marked in body and spirit.

Nunca Mas. Never Again. 2022. Courtesy of Vicente Chapero.

In Western terms, Marvyn suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Like diabetes or heart disease, PTSD is a comorbidity factor for many illnesses, including Covid-19. Healthy and fully vaccinated, Marvyn, now 53, delayed seeking medical treatment when he began to experience Covid symptoms. Trained in Western medicine, Marvyn has practiced medicine in a variety of settings in Guatemala and Mexico, he is now a doctor and professor of the healing arts in Los Angeles. Yet he did everything possible to avoid the institutionalization and loss of autonomy that accompanies hospitalization.

Reflecting on his hesitancy to seek treatment, he said, “It is just not the same to be in a hospital as a patient as it is to be part of the health staff.” After five weeks of symptoms and dependent on oxygen, he finally sought medical treatment at a Los Angeles hospital. I offered to speak with the attending physician on the phone to explain Marvyn’s PTSD because intake interviews do not routinely include questions about surviving torture or violence. In the best of circumstances, it is difficult for torture survivors to raise the issue of their suffering.

Marvyn and I have been texting because his labored breathing makes it difficult to speak and talking tires him quickly.

He texted me that Covid-19 was triggering his PTSD, especially when he was social distancing in quarantine. “To be completely isolated in a room and struggling to breathe reminded me of the times they subjected me to the capucha,” he explained, “the exhaustion, the weakness, the inability to sleep, the interminable nights” brought the nightmare memories to life.

When Marvyn was gravely ill with Covid, the nights terrified him because the symptoms came in more intense and longer waves in the pre-dawn hours. He left his bedroom curtains open so he could see the sunrise and know that he was still alive for another day. As Marvyn struggled for each breath, he wrote “It felt like I was in the clandestine jail in that house where the nights were equally long and terrorizing.” He remembered the long wait in darkness for “the rooster to crow announcing the breaking of dawn.”

Fall 2018, Volume XVIII, Number 1

Victoria Sanford (Bunting ‘00) is the author of Buried Secrets: Truth & Human Rights in Guatemala and Bittersweet Justice: Feminicide and Impunity in Guatemala (forthcoming). She is currently completing The Vanished of Guatemala: Violence, Corruption and the Invention of Forced Disappearance.