FRITANGAS

Street Artifacts and Domestic Mutations

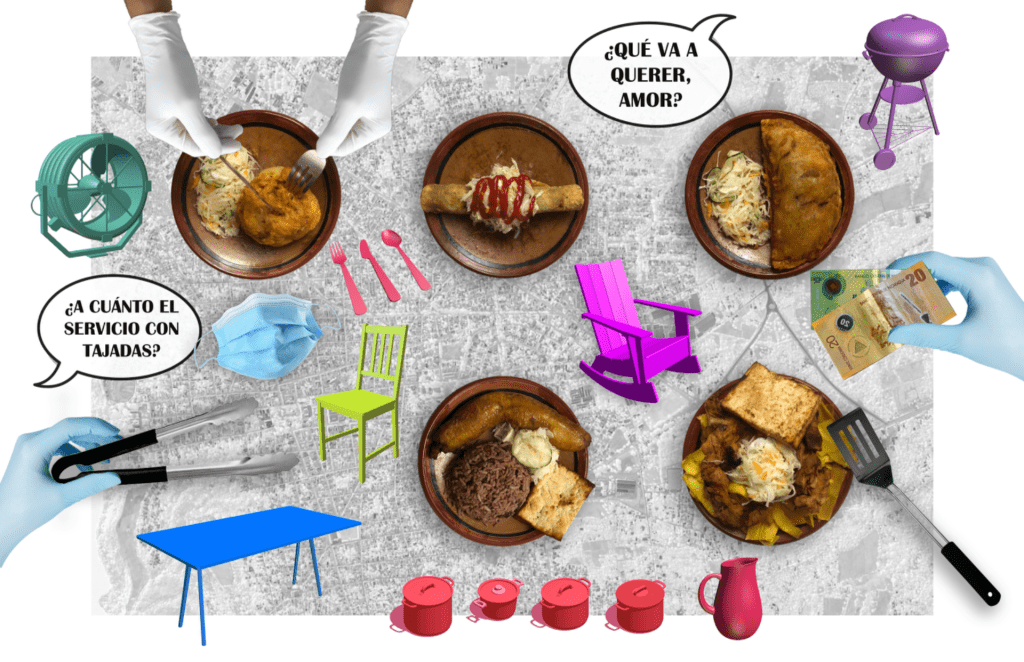

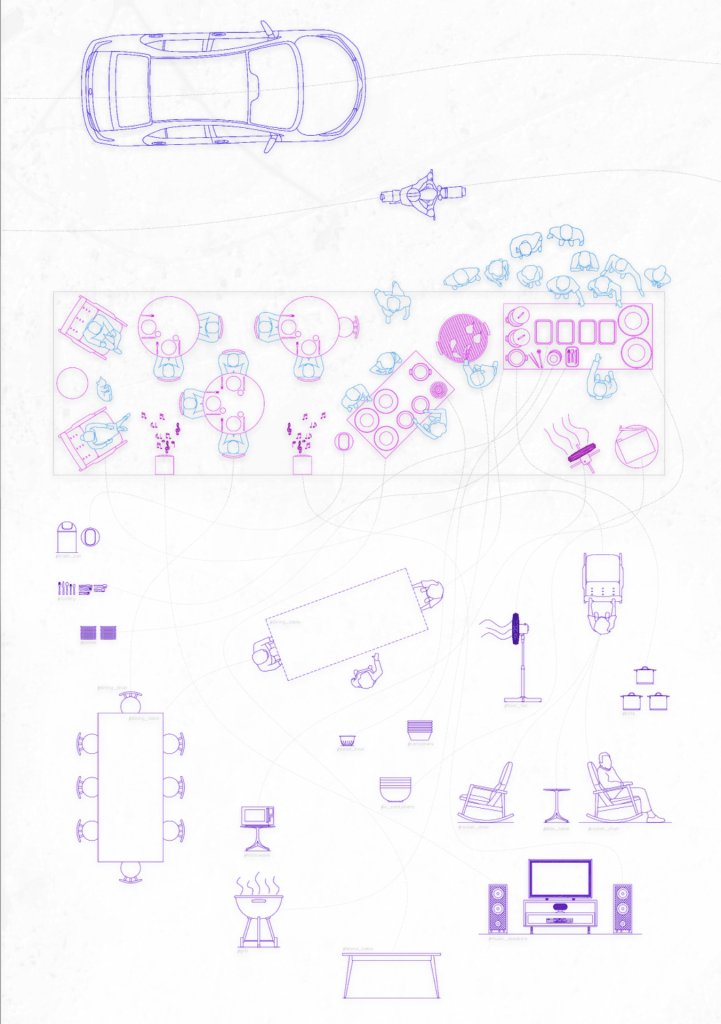

The fritanga mapping, a staging of domestic mutations and urbanity. Diagram: Oscar M Caballero

In Latin America, a house is a family heirloom that gets passed on for generations. It is a product of its time. One might see it as an avatar that can constantly change to accommodate new features and dispose of others. In the process of generating change, what happens when the street becomes an extension of the house? It becomes a type of “zone zero” in which rules are yet to be defined, spatial transformations are rarely regulated and urban accountability is reluctantly challenged.

In the current Covid-19 transition period, the turmoil around understanding human activities by redefining forms of living, working and interacting has entailed a thorough quest for entrepreneurship models. Nicaragua, the land of lakes and volcanoes, is an interesting case study of a female-driven economy as a means to cope with the nationwide socio-political crisis and the global health reckoning. According to the UN Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, also known as UN Women, 59% of women in Latin America and the Caribbean work in the informal economy.

In Nicaragua, fritangas are traditional street food businesses, originally informal but sometimes evolving into restaurants. Regardless of their architectural setting, they exist as an effort to heal a fractured economy and create urban nodes that, unintentionally and through their ubiquitous nature, influence much local contemporary culture and gastronomy. Over time, women are setting up more and more of these businesses. Partly due to the pressing post-pandemic economy that has created loopholes for this line of work to expand. This type of informal business can keep a household afloat, built from scraps of the domestic body to create a new body of work.

Tacit Matriarchy

Growing up in Masaya, a small town located about 20 miles from the capital, I saw clearly that the participation of women as a labor force had a tangible impact on the city’s economy. This unspoken and mostly overlooked role starts from within daily operations in the household, often supported and maintained by a matriarchal character. Somehow, heteronormative gender roles that segregate women into a domestic setting also permit the flourishing of unconventional models of self-reliant governance.

Since the society focuses on the nuclear family and is generally unresponsive to the needs of others, matriarchs have had to seek ways to make money beyond their limitations. Historically in Masaya, women carry out an important role in the local economy through informal businesses for the most part. Many of those have a domestic provenance, such as the sale of food or drinks prepared at home and sold on the streets: grilled corn, tortillas, boiled beans, cheese stands or even traditional desserts, to name a few. Marchantas sell fruits and vegetables on carts or warm sweet bread on bateyas moving across the streets either alone or with a family member. The urban landscape echoes the voices of women advertising their products every hour of the day, either on the streets, in their homes, and most recently—as a consequence of the pandemic—through social media platforms with touchless delivery.

The alliance between domestic and labor models provides an opportunity to stay close to family and rely on the home. In many ways, the matriarchal framework already had something to learn from when the Covid-19 pandemic waves turned the focus to home spaces for sources of remote working with limited human interaction. However, in Nicaragua, one could say social isolation started two years before the outbreak of the virus in 2020 when a wave of governmental actions drove citizens to protest. The unleashed violence and crimes against humanity by government forces affected the dynamics of how people lived and worked in their immediate environment. Due to the speed at which violence escalated, the cities rapidly shapeshifted their streets to endure the government forces’ attacks. The street paver blocks were repurposed as barricades, light posts blinked in disharmony and window blinds were shot permanently. The public realm was no longer safe and people took shelter in their homes by fear of repression and persecution. When government forces took control over the entire urbanscape, the domestic segregation had become the new living standard. This is how, by the time Covid-19 became a global affliction, Nicaragua only worsened and lengthened one of its most dreadful moments in history.

Aftermath

Hundreds of people attend the caravan organized by the government amidst the most infectious time for Covid-19 in the country. Managua Nicaragua. Photograph by Oswaldo Rivas_Reuters.

The coronavirus in Nicaragua carved a deep wound and set the clock back to an unprecedented but somehow relatable state of uncertainty. The similarities between the pandemic afflictions and the consequences of past socio-political crisis are many. To mention a few: communal graves, food rationing and injection of propaganda. Only this time the health component would worsen to a lethal stage. In March 2020, the government conducted a misinformation campaign about the management, spread and even existence of the virus in the country. Its response to the health crisis was ludicrous, exacerbating the situation by organizing mass caravans in different cities under the slogan: “Amor en Tiempos de Covid-19,” a play of words on Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez’ Love in the Time of Cholera. After two years of dealing with the aftermath of the pandemic, human loss, unemployment and mass migration, the country faces an unknown future. However, to understand the current context, it is necessary to look back at 2018.

According to the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), after a two-year recession caused by the 2018 sociopolitical crisis, Nicaragua suffered further drops in economic activity due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the two major 2020 hurricanes. Therefore, geopolitics, health and climate collided with each other for a devastating territorial shift from four decades of a slow post-war convalescence to a tumultuous period of survival of the fittest.

As the stories became scarier, vital goods more limited, and opportunities more scattered, life still went on, somehow, with Nicaraguans scavenging for ways to make it through the days. Harnessing domestic confinement produced a wave of entrepreneurship, and women were leading the way by increasing their experience in informal economies. At a distance, friends and family would mention to me every now and then how a new small business or venture, including the women in my own family, started navigating once more through a time of survival resourcefulness. Fritangas spread like wildfire across the cities, taking over sidewalks and displaying an enduring model for those who remain in the country amid its slow socioeconomic decay.

Lego House

Diagram of fritanga components by Oscar M Caballero.

Undoubtedly, a fritanga is a living type of architecture that extracts its parts from household items to build an appendix that will only live on borrowed time every day for a few hours until returning to its original body. In the same way that the Metropolitan Museums Cloisters in upper Manhattan is a staging of a building made of buildings, a fritanga is an assemblage of the patrimony we hold on to—“una puesta en escena” (stage)— in which characters get to play a second role. No two fritangas are the same, since they adapt to their idiosyncratic spatial conditions. The combination of selected objects that are reused and the rearrangeable spaces jointly provide a unique composition. The dynamic of these street artifacts is as volatile as their construction and as unmethodical as their programming. They rarely adhere to zoning regulations, how could they? They lack a permanent body.

Setting up a fritanga involves food preparation, food displaying and serving or dispatching. Each of these tasks will originate from a primary space to perform its function. The domestic anatomy gets temporarily shifted as the house makes room to host a new program. The front porch—or sidewalk— is the dedicated stage to perform the fritanga. Other vital spaces fulfill an important role; the kitchen is the core of all operations, either as a centralized space to cook all the food or by the addition of an improvised cooking station in situ—usually a grill. The living and dining rooms are dismantled, and their components are brought to the front in a kind of supportive role to either display food in pots, provide seating for customers, or as a scenography to create a pleasant atmosphere. The domestic user, too, becomes a shapeshifter, as an understudy ready to take on the necessary roles as the cook, food or drinks dispatcher, spokesperson, cashier or all of the above.

Beyond the architectural implications of these domestic programmatic mutations, the space becomes only the backdrop. The real plot is developed as a tracking circuit, an effective network of positions: resting state, in-motion and performance. A mechanism triggered by invisible lines of action at the cue of an improvised choreography. Lasting a few hours to then put everything back to where it belongs and restart again the next day.

Long Overdue

National organizations monitoring the country’s development predicted economic improvement in 2022, attributing the projected growth to tourism, agriculture and exports. However, interesting enough, none specifically mentioned the contribution of informal economies led by women. While hope is seen for the economy attempts to move forward, life in Nicaragua continues to stagnate. The country continues to diminish its quality of life amid a deep crisis of human rights, corruption and freedom of speech. I believe Nicaraguans will continue to endure and find a path; just as fritangas provide a temporary truce between motionless geopolitics and the never-ending limbo that holds the country in a state of constant recession.

- Domestic fritanga. Calle Libertad, Granada, Nicaragua, 2022. Photo by Franck Meléndez.

- Domestic fritanga. Calle El Martirio, Granada, Nicaragua, 2022. Photo by Franck Meléndez.

- Domestic fritanga. Calle San Juan del Sur, Granada, Nicaragua, 2022. Photo by Franck Meléndez.

- Domestic fritanga. Calle Libertad, Granada, Nicaragua, 2022. Photo by Franck Meléndez.

FRITANGAS

Artefactos urbanos & Mutaciones Domésticas

Por Oscar M Caballero

En Latinoamérica, una casa es una reliquia familiar que es heredada por generaciones. Es un producto de cada época. Se podría interpretar como un avatar que cambia constantemente para integrar nuevas características y deshacerse de otras. En el proceso de generar cambio, ¿qué sucede cuando el espacio urbano se convierte en una extensión de la casa? Se crea una especie de “zona cero” en la que las reglas aún no se han definido, las transformaciones espaciales rara vez se regulan y el implemento de la legislación urbana opone resistencia.

En el actual período transitorio de Covid-19, la conmoción alrededor del estudio de actividades humanas mediante la reestructuración de formas de vivienda, trabajo e interacción social ha supuesto una búsqueda exhaustiva de modelos de emprendedurismo. Nicaragua, la tierra de lagos y volcanes, presenta el caso de estudio interesante de una economía impulsada por mujeres como un medio para hacer frente a la crisis sociopolítica a nivel nacional y a la crisis de salud mundial. Según la Entidad de la ONU para la Igualdad de Género y el Empoderamiento de las Mujeres, también conocida como ONU Mujeres, el 59% de las mujeres en América Latina y el Caribe trabaja en la economía informal.

En Nicaragua, las fritangas son negocios urbanos de comida tradicional, originalmente informales, pero a veces evolucionan en restaurantes. Sin importar su configuración arquitectónica, existen como un intento de elevar una economía en deterioro y crear nodos urbanos que, sin planificación y por medio de su ubicuidad, influencian gran parte de la cultura y gastronomía local contemporánea. En los últimos años, las mujeres están liderando cada vez más estos negocios. En parte debido a la apremiante economía post pandémica que ha creado el espacio para que esta línea de trabajo se expanda. Este tipo de negocio informal puede mantener a flote un hogar, construido a partir del reuso de elementos del espacio doméstico para crear un nuevo espacio de trabajo.

Matriarcado Tácito

Al crecer en Masaya, un pequeño pueblo localizado alrededor de 30km de la capital, pude ver claramente que la participación de la mujer como una fuerza laboral tenía un impacto tangible en la economía urbana. Este rol tácito y mayormente pasado por alto comienza dentro de las operaciones diarias en el hogar, a menudo respaldado y mantenido por un carácter matriarcal. De alguna manera, los roles de género heteronormativos que segregan a las mujeres en un entorno doméstico también permiten el desarrollo de modelos no convencionales de manutención autónoma.

Dado que la sociedad se enfoca en el modelo convencional de la familia nuclear y generalmente no responde a las necesidades de otros modos de domesticidad, las matriarcas han tenido que buscar formas de ganar dinero más allá de sus limitaciones. Históricamente en Masaya, las mujeres desempeñan un papel importante en la economía local a través de negocios informales en su mayoría. Muchos de ellos tienen una procedencia doméstica, como la venta de comidas o bebidas preparadas en casa y vendidas en la calle: elotes asados, tortillas, frijoles cocidos, puestos de queso o incluso postres tradicionales, por mencionar algunos. Las marchantas venden frutas y verduras en carretones o pan dulce caliente en bateyas que recorren las calles, ya sea solas o con un miembro de la familia. El paisaje urbano hace eco de las voces de las mujeres que anuncian sus productos a toda hora del día, ya sea en las calles, en sus hogares y, más recientemente, como consecuencia de la pandemia, a través de plataformas de redes sociales con entrega sin contacto.

La alianza entre los modelos domésticos y laborales brinda la oportunidad de permanecer cerca de la familia y el hogar. En muchos sentidos, el sistema matriarcal ya era una referencia de aprendizaje cuando las olas de la pandemia de Covid-19 cambiaron el enfoque hacia los espacios domésticos para fuentes de trabajo remoto con interacción humana limitada. Sin embargo, en Nicaragua, se podría decir que el aislamiento social comenzó dos años antes del brote del virus en 2020 cuando una ola de acciones gubernamentales llevó a los ciudadanos a protestar. La violencia y los crímenes de lesa humanidad desatados por las fuerzas gubernamentales afectaron la dinámica de vida y trabajo de las personas en su entorno inmediato. Debido a la velocidad a la que escaló la violencia, las ciudades cambiaron la morfología de sus calles rápidamente para sobrevivir los ataques de las fuerzas policiales y paramilitares. Los bloques de adoquines de las calles se utilizaron como barricadas, los postes de luz parpadeaban a destiempo y las persianas de las ventanas se cerraron permanentemente. El espacio público ya no era seguro y la gente se refugiaba en sus casas por miedo a la represión y persecución. Cuando las fuerzas gubernamentales tomaron el control de todo el paisaje urbano, la segregación doméstica se había convertido en el nuevo estándar de vida. Es así como, para cuando el Covid-19 se convirtió en una aflicción mundial, Nicaragua solo empeoró y alargó uno de los momentos más oscuros de su historia.

Secuelas

En Nicaragua, el coronavirus abrió una herida profunda y retrasó el tiempo a un estado de incertidumbre sin precedentes pero de alguna manera identificable. Las similitudes entre las aflicciones de la pandemia y las consecuencias de la crisis sociopolítica del pasado son muchas. Por mencionar algunas: fosas comunes, racionamiento de alimentos y promulgación de propaganda. Solo que esta vez el componente de salud empeoraría a un nivel letal. En marzo de 2020, el gobierno realizó una campaña de desinformación sobre el manejo, la propagación e incluso la existencia del virus en el país. Su respuesta a la crisis sanitaria fue absurda, agudizando la situación al organizar caravanas masivas en diferentes ciudades bajo el lema: “Amor en Tiempos de Covid-19”, un juego de palabras sobre El amor en los tiempos del cólera del autor colombiano, Gabriel García Márquez. Después de dos años de lidiar con las secuelas de la pandemia, la pérdida humana, el desempleo y la migración masiva, el país enfrenta un futuro incierto. Sin embargo, para entender el contexto actual, es necesario entender los acontecimientos en 2018.

Según el Banco Internacional de Reconstrucción y Fomento (BIRF), luego de una recesión de dos años provocada por la crisis sociopolítica de 2018, Nicaragua sufrió nuevas caídas en la actividad económica debido a la pandemia de Covid-19 y dos grandes huracanes de 2020. Por lo tanto, factores de carácter geopolítico, sanitario y climático colisionaron entre sí para generar un devastador cambio territorial, transicionando de cuatro décadas de una lenta convalecencia de posguerra a un tumultuoso período de supervivencia.

A medida que la situación sociopolítica se agudizaba, los bienes vitales eran limitados y las oportunidades más dispersas, la vida continuaba, de alguna manera, con los nicaragüenses buscando formas de sobrevivir. Aprovechar el confinamiento doméstico produjo una ola de emprendimiento, y las mujeres estaban liderando el camino usando su experiencia en economías informales. A la distancia, amigos y familiares me comentaban de nuevos emprendimientos, incluso las mujeres de mi propia familia, comenzaron a navegar una vez más a través de una época de ingenio de supervivencia. Las fritangas se extendieron como pólvora por las ciudades, invadiendo las aceras y mostrando un modelo de negocio para quienes permanecen en el país en medio de su lenta decadencia socioeconómica.

Ensamblaje

Una fritanga, sin suda, es un tipo de arquitectura viva que extrae sus partes de componentes caseros para construir un apéndice que solo existirá temporalmente cada día durante unas horas hasta volver a su cuerpo original. Así como el Metropolitan Museums Cloisters en Manhattan exhibe la composición de un edificio hecho de edificios, una fritanga es el ensamblaje del patrimonio que atesoramos —“una puesta en escena”— en el que los personajes llegan a desempeñar un segundo papel. No hay dos fritangas iguales, ya que se adaptan a la idiosincrasia de cada espacio. La combinación de objetos seleccionados que se reutilizan y los espacios reorganizables en conjunto proporcionan una composición única. La dinámica de estos artefactos urbanos es tan volátil como su construcción y tan poco metódica como su programación. Raramente obedecen a las regulaciones urbanas, ¿cómo podrían hacerlo? Si carecen de un cuerpo permanente.

La instalación de una fritanga implica la preparación de alimentos, la exhibición de alimentos y el servicio de atención o envío. Cada una de estas tareas partirá de un espacio primario para realizar su función. La anatomía doméstica cambia temporalmente a medida que la casa hace espacio para albergar un nuevo programa. El porche delantero, o acera, es el escenario elegido para instalar la fritanga. Otros espacios vitales cumplen un papel importante; la cocina es el núcleo de todas las operaciones, ya sea como un espacio centralizado para cocinar todos los alimentos o mediante la adición de una estación de cocción improvisada in situ, generalmente una parrilla. La sala y el comedor se desmantelan y sus componentes se trasladan al frente en una especie de papel de apoyo para exhibir alimentos en ollas, proporcionar asientos para los clientes o como una escenografía para crear una atmósfera agradable. El usuario doméstico también se convierte en un suplente listo para asumir los roles necesarios como cocinero, despachador de alimentos o bebidas, vocero, cajero o todos los anteriores.

Más allá de las implicaciones arquitectónicas de estas mutaciones programáticas domésticas, el espacio se convierte en un telón de fondo. La trama real se desarrolla como un circuito de rotaciones, una red efectiva de posiciones: estado de reposo, en movimiento y actuación. Un mecanismo desencadenado por líneas de acción invisibles al son de una coreografía improvisada. Durando unas horas para luego volver a poner todo en su lugar y reiniciar de nuevo al día siguiente.

Expiración tardía

Organismos nacionales que monitorean el desarrollo del país pronosticaron una mejora económica en 2022, atribuyendo el crecimiento proyectado al turismo, la agricultura y las exportaciones. Sin embargo, ninguno mencionó específicamente la contribución de las economías informales dirigidas por mujeres. Mientras se vislumbra esperanza de que la economía intente salir adelante, la vida en Nicaragua continúa estancada. El país sigue mermando su calidad de vida en medio de una profunda crisis de derechos humanos, corrupción y libertad de expresión. No obstante, creo que los nicaragüenses seguirán persistiendo y encontrando un camino; así como las fritangas brindan una tregua temporal entre la geopolítica inmóvil y el limbo interminable que mantiene al país en un estado de recesión constante.

Oscar M Caballero es un arquitecto, investigador y artista visual originario de Masaya, Nicaragua. Tiene un Master en Diseño Arquitectónico Avanzado por Columbia University. Es el autor de Ghost Monuments, publicado por Monument Lab.

Related Articles

Haiti: A Gangster’s Paradise

Haiti is in the news. In recent weeks, gangs have coordinated violent actions, taken to the streets and liberated thousands of inmates to spread chaos and solidify their control of the Port-au-Prince capital.

Crime and Punishment in the Americas

As 2024 ushered in, newly-elected Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa issued a state of emergency in his country, citing a wave of gang violence spurred by the prison escape of a local criminal leader with ties to Mexico’s ruthless Sinaloa Cartel.

Women CEOs in Latin America: Overcoming obstacles, navigating through challenges

I first arrived in Latin America in 1997, and since then, I’ve been involved in education and the development of leadership and governance issues in the region. During these 27 years—12 of them from Spain—I have had the opportunity to interact with leaders from the region, the private and public sectors, multinationals and small and medium-sized enterprises, and various industries.